What do you think?

Rate this book

372 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1967

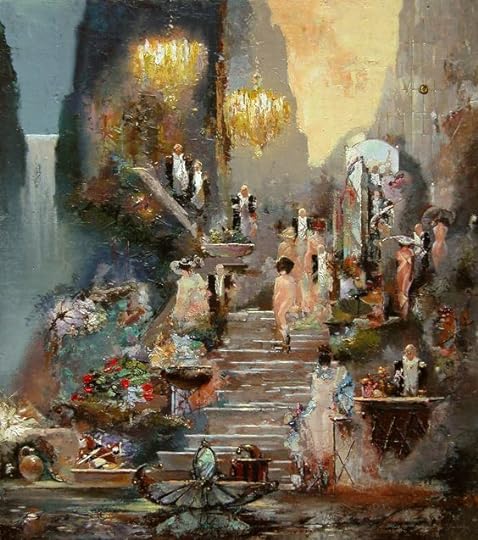

"What would your good be doing if there were no evil, and what would the earth look like if shadows disappeared from it? After all, shadows are cast by objects and people. There is the shadow of my sword. But there are also shadows of trees and living creatures. Would you like to denude the earth of all the trees and all the living beings in order to satisfy your fantasy of rejoicing in the naked light? You are a fool."What is this book about? I wish it were easy to tell in one smartly constructed sentence, but luckily it's not. It is a story of Woland, the Satan, coming to Moscow with his retinue and wrecking absolute havoc over three long and oppressively hot summer days. It is a story of Pontius Pilate (the equestrian, the son of the astrologist-king, the last fifth Procurator of Judea) who has achieved the dreaded immortality due to a single action (or rather INaction) and wishes nothing more than for it to not have happened. It is a story of love between two very lonely people. It is a scaldingly witty story about the oppressive nature of early Stalin days and the rampant Soviet bureaucracy. It is a phantasmagorical story of the supernatural and the mythical. It has elements of humorous realism, romanticism, and mysticism. It is all of the above and much more. As doctors (the same profession that Bulgakov belonged to, by the way!), we are taught to look for the bigger picture, the synthesis of facts, the overall impression, the so-called 'gestalt'. Well, the gestalt here is - it's a true masterpiece.

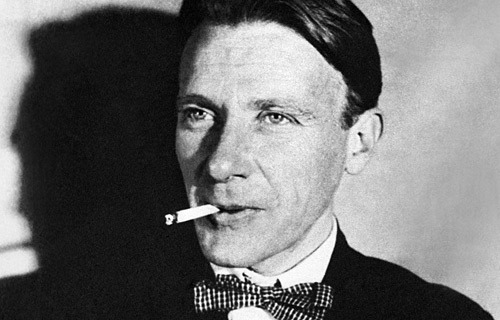

"Manuscripts do not burn.""Bulgakov wrote this book over a period of 11-12 years, frequently abandoning it, coming back to it, destroying the manuscripts, rewriting it, abandoning it, and coming back to it again. He wrote it during the times when the reaction to such novels would have been the same as Woland has when hearing Master say he wrote a novel about Pontius Pilate:

"About what, about what? About whom?" - said Woland, having stopped laughing. - "In these times? It's amazing! And you couldn't find a different subject?"In these times... The 1930s were the time of Stalin's rule, the waves of Purges, the paranoia of one powerful man sweeping the country, the denunciations, the lies, the terror, the fear, the accusations, the senseless arrests, the nondescript black cars pulling up to the apartment buildings in the middle of the night and leaving with people who would not be heard from ever again. This was a suffocating atmosphere, and the only way Bulgakov survived it was that he for reasons unknown enjoyed the whimsical favor of the tyrant. This fear is everywhere, on every single page. From the poor unfortunate Berlioz in the early chapters, who without much hesitation is about to contact the authorities to report about a suspicious 'foreigner' to the unnamed people conducting the investigation of the strange Moscow events and puling the victims in for questioning to Rimskiy sending Varenukha with a packet of information for the 'right people' to Master's terrifying and unheard story starting with 'them' knocking on his window and ending with him broken in the mental institution... The fear is everywhere, thinly veiled. And yet it is never named, even once - the name of those causing the fear, never alluded to - no need for it, it's obvious anyway, and besides there's that age-long superstition about not naming the name of evil, which, funnily, in this novel is definitely NOT the Devil. Only Margarita has the guts to ultimately ask, "Do you want to arrest me?"

------------------------

"You're not Dostoevsky,' said the citizeness, who was getting muddled by Koroviev.The sharp satire of the contemporary to Bulgakov Soviet life of the 1930s is wonderful, ranging from deadpan observations to witty remarks to absolute and utter slapstick (that, of course, involving the pair of Korovyev and Behemoth). It can be sidesplittingly funny one second, and in the next moment become painfully sad and very depressing. Not surprisingly - in the Russian tradition humor and sadness have always walked hand in hand; therefore, for instance, Russian clowns are the saddest clowns in the entire universe, trust me. This funny sadness manages to evoke the widest spectrum of emotional responses from me every single time I read this book, never ever failing at this.

'Well, who knows, who knows,' he replied.

'Dostoevsky's dead,' said the citizeness, but somehow not very confidently.

'I protest!' Behemoth exclaimed hotly. 'Dostoevsky is immortal!"

"The only thing that he said was that he considers cowardice to be among the worst human vices."This book is not only the hilariously sad commentary on the realities of Bulgakov's contemporary society; it is also a shrewd commentary on the never-changing nature of humanity itself. The humanity that Woland wanted to observe in the Variety theatre, until he came to the sad but true conclusion that not much changed in them. The cowardice - the vice that Pilate feels Yeshua Ha-Nozri was implicitly accusing him of. The greed and love of money, leading to heinous crimes like treason and deceit and treachery. The egoism and vanity and self-absorption (just think of the talentless poet Ryukhin's anger at the seemingly lucky circumstances of Pushkin's fame!), the close-mindedness and complacency, the hate and bickering. This is all there, sadly exposed and gently (or sometimes not that gently) condemned. The consequences of this humanity shown in their extreme - think of Ryukhin's craving for immortality and Pilate's terror at facing it.

"The one who loves must share the fate of the one he loves."I love this book, love it more than I could ever hope to express in words. I can write endless essays about each chapter, approach it from each imaginable angle, analyze each one precisely and masterfully crafted phrase. I could do it for days - and yet still not pay due respect to this incredible work of art. Because it has the best kind of immortality. Because its depth is unrivaled. Because it is the work of an incredible genius. And so I will stop my feeble attempts to do it justice and instead will remain behind, like the needled memory of poor Professor Ponyrev, formerly Ivanushka Bezdomny, Master's last and only pupil, left to remember the unbelievable that he once witnessed and that broke his heart and soul.

"...And master's memory, the restless, needled memory, began to fade. Someone was setting master free, just like he himself set free the hero he created. This hero left into the abyss, left irrevocably, forgiven on the eve of Sunday son of astrologer-king, the cruel fifth Procurator of Judea, equestrian Pontius Pilate."

To tell the truth, it took Arkady Apollonovich not a second, not a minute, but a quarter of a minute to get to the phone.I ask this question in complete earnestness: is this supposed to be funny? I have absolutely no idea.

Quite naturally there was speculation that he had escaped abroad, but he never showed up there either.Huh?

The bartender drew his head into his shoulders, so that it would become obvious that he was a poor man.Yeah, I give. I don’t even pretend to understand what this means. Anyhoo, hey—it’s been a pleasure meeting you all; we should do this again soon. Toodle-oo!

First of all, the man described did not limp on any leg, and was neither short nor enormous, but simply tall. As for his teeth, he had platinum crowns on the left side and gold on the right. He was wearing an expensive grey suit and imported shoes of a matching colour. His grey beret was cocked rakishly over one ear; under his arm he carried a stick with a black knob shaped like a poodle’s head. He looked to be a little over forty. Mouth somehow twisted. Clean-shaven. Dark-haired. Right eye black, left – for some reason – green. Dark eyebrows, but one higher than the other. In short, a foreigner.

Follow me, reader! Who told you that there is no true, faithful, eternal love in this world! May the liar’s vile tongue be cut out!

Follow me, my reader, and me alone, and I will show you such a love!

No! The master was mistaken when with bitterness he told Ivanushka in the hospital, at that hour when the night was falling past midnight, that she had forgotten him. That could not be. She had, of course, not forgotten him.

First of all let us reveal the secret which the master did not wish to reveal to Ivanushka. His beloved’s name was Margarita Nikolaevna. Everything the master told the poor poet about her was the exact truth. He described his beloved correctly. She was beautiful and intelligent.

“These good people,” the prisoner began, hastily added “Hegemon” and continued: “learnt nothing and muddled up all I said. In general, I’m beginning to worry that this muddle will continue for a very long time. And all because he records what I say incorrectly.”This is a direct attack on the ‘veracity’ of the gospel of Matthew. Bulgakov here implicitly contrasts religion against literature in his expanded and reinterpreted version of the biblical story of Jesus's condemnation and death; and he comes down decisively for literature as the more fundamental mode of thinking. The only thing beyond a text is... another text.

"Would you be so kind as to give a little thought to the question of what your good would be doing if evil did not exist, and how the earth would look if the shadows were to disappear from it? After all, shadows come from objects and people."

"Of course, when people have been completely pillaged, like you and me, they seek salvation from a preternatural force!"And he is immediately corrected by Margarita, the new Eve with eminent practicality, "Preternatural or not preternatural –isn’t it all the same? I’m hungry.”

“son como todas las personas. Les gusta el dinero, pero eso siempre fue así… La humanidad ama el dinero, no importa de qué esté hecho, si de piel, de papel, de bronce o de oro. Bueno, son frívolos… Pero ¿y qué? A veces la misericordia también llama a sus corazones…”.El bien y el mal se aúnan y son inseparables:

“¿Qué haría tu bien si no existiera el mal y qué aspecto tendría la tierra si desaparecieran las sombras? Los hombres y los objetos producen sombras. Ésta es la sombra de mi espada. También hay sombras de árboles y seres vivos. ¿No querrás raspar toda la tierra, arrancar los árboles todo lo vivo para gozar de la luz desnuda? Eres un necio.”

“cualquier autoridad es una violencia sobre los hombres y llegará el día en que no existirá el poder de los césares ni ningún otro. El hombre entrará en el reino de la verdad y de la justicia donde no será necesario ningún poder.”Y ello gracias a que

”No hay hombres malos en la tierra.”El lector tendrá que dilucidar la cuestión por su cuenta. Yo solo digo que: