"Although I have always resented the title ‘Peanuts‘ which I was forced to use – and I’m still convinced it’s the worst title for any comic strip – it probably doesn’t matter what it is called so long as each effort brings some kind of joy to someone, someplace. My work is extremely satisfying and to be able to draw Snoopy, Charlie Brown, Lucy and all the other little characters and to know that people love them and care about what happens to them makes my work extremely satisfying."

Charles M. Schulz (1979)

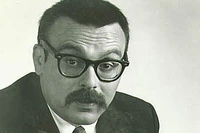

Charles M. Schulz drawing Snoopy.

Peanuts is a syndicated daily and Sunday comic strip written and illustrated by Charles M. Schulz, which ran from October 2, 1950, to February 13, 2000 (the day after Schulz's death). In total 17,897 different Peanuts strips were published. The strip was one of the most popular and influential in the history of the medium, and considered the most beloved comic strips of all time. It was "arguably the longest story ever told by one human being", according to Professor Robert Thompson of Syracuse University. At its peak, Peanuts ran in over 2,600 newspapers, with a readership of 355 million in 75 countries, and was translated into 21 languages. It helped to cement the four-panel gag strip as the standard in the United States. Reprints of the strip are still syndicated and run in many newspapers.

In addition, Peanuts achieved considerable success for its television specials, several of which, including A Charlie Brown Christmas and It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown won or were nominated for Emmy's. The holiday specials remain quite popular to this day, and are currently are on the Apple TV+ streaming service.

History[]

Peanuts 1940s[]

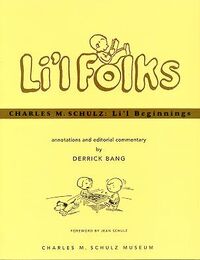

Front cover of a collection of Li'l Folks comic strips.

Peanuts had its origin in Li'l Folks, a weekly panel comic that appeared in Schulz's hometown paper, the St. Paul Pioneer Press, from June 1947 to January 1950, with 141 strips in total. Schulz first used the name Charlie Brown for a character there, although he used the name on four different occasions in Li'l Folks for different boys. The series also featured a dog that looked a lot like Snoopy. In 1948, Schulz sold a cartoon to the Saturday Evening Post; seventeen single-panel cartoons by Schulz would be published there.

In 1948, Schulz tried to have Li'l Folks syndicated through the Newspaper Enterprise Association. Schulz would have been an independent contractor for the syndicate, unheard of in the 1940s, but the deal fell through. Li'l Folks was dropped in 1949. The next year, Schulz approached the United Features Syndicate with his best work from Li'l Folks.

When his work was picked up by United Features Syndicate, they decided to run the new comic strip he had been working on. This strip was similar in spirit to the panel comic, but it had a set cast of characters, rather than different nameless little folk for each page. Unfortunately, the name Li'l Folks was too similar to the names of two other comics of the time: Al Capp's Li'l Abner and a now-forgotten strip titled Little Folks. To avoid confusion, the syndicate settled on the name Peanuts, a title Schulz always disliked. In a 1987 interview, Schulz said of the title Peanuts: "It's totally ridiculous, has no meaning, is simply confusing, and has no dignity — and I think my humor has dignity". The periodic collections of the strips in paperback book form typically had either "Charlie Brown" or "Snoopy" in the title, not "Peanuts", due to Schulz's distaste for his strip's title. The Sunday panels eventually typically read, Peanuts, featuring Good Ol' Charlie Brown.

Peanuts 1950s[]

The first Peanuts comic strip from October 2, 1950.

Peanuts premiered on October 2, 1950 in seven newspapers nationwide: The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The Minneapolis Tribune, The Allentown Call-Chronicle, The Bethlehem Globe-Times, The Denver Post and The Seattle Times. It began as a daily strip; its first Sunday strip appeared January 6, 1952, in the half page format, which was the only complete format for the entire life of the Sunday strip.

Snoopy in early 1950s

By 1959, only eleven characters had beeen introduced, namely Charlie Brown, Shermy, Patty, Snoopy, Violet, Schroeder, Lucy, Linus, Pig-Pen, Charlotte Braun and Sally. There were no minor characters, except for Charlotte Braun, although she was not originally supposed to be one.

Charlotte Braun made a very limited number of appearances in the Peanuts strip.

By the time the first Peanuts Sunday strip appeared, the dailies had been reduced from full page strips to a mere four panels. While this reduced the capacity for artistic expression, the shortage of space allowed Schulz to create a new style for the medium. Schulz made the decision to produce all aspects of the strip, from the script to the finished art and lettering, himself. Thus the strip was able to be presented with a unified tone, and Schulz was able to employ a minimalistic style. Backgrounds were generally eschewed, and when utilised Schulz's frazzled lines imbued them with a fraught, psychological appearance. This style has been described by art critic John Carlin as forcing "its readers to focus on subtle nuances rather than broad actions or sharp transitions."

While the strip in its early years resembles its later form, there are significant differences. The art was cleaner and sleeker, though simpler, with thicker lines and short, squat characters. For example, in these early strips, Charlie Brown's famous round head is closer to the shape of a football. In fact, most of the kids were initially fairly round-headed.

Peanuts 1960s–1990s[]

"5", a Peanuts character introduced in 1963.

Peanuts is remarkable for its deft social commentary, especially compared with other strips appearing in the 1950s and early 1960s. Schulz did not explicitly address racial and gender equality issues so much as he assumed them to be self-evident in the first place. Peppermint Patty's athletic skill and self-confidence is simply taken for granted, for example, as is Franklin's presence in a racially-integrated school and neighborhood.

Schulz could throw barbs at any number of topics when he chose, though. Over the years he tackled everything from the Vietnam War to school dress codes to the "new math". One of his most prescient sequences came in 1963 when he added a little boy named "5" to the cast, whose sisters were named "3" and "4", and whose father had changed the family surname to their ZIP Code to protest the way numbers were taking over people's identities. In 1957, a strip in which Snoopy tossed Linus into the air, and boasted that he was the first dog ever to launch a human, parodied the hype associated with Sputnik 2's launch of "Laika" the dog into space earlier that year. Another sequence lampooned Little Leagues and "organized" play, when all the neighborhood kids join snowman-building leagues and criticize Charlie Brown when he insists on building his own snowmen without leagues or coaches..

Peanuts touched on religious themes on many occasions, most notably in the classic television special A Charlie Brown Christmas in 1965, which features the character Linus van Pelt quoting the King James Version of the Bible (Luke 2:8-14) to explain to Charlie Brown "what Christmas is all about." (In personal interviews, Schulz mentioned that Linus represented his spiritual side.)

Peanuts probably reached its peak in American pop-culture awareness between 1965 and 1980; this period was the heyday of the daily strip, and there were numerous animated specials and book collections. During the 1980s other strips rivaled Peanuts in popularity, most notably Doonesbury, Garfield, The Far Side, Bloom County, and Calvin and Hobbes. However, Schulz still had one of the highest circulations in daily newspapers.

The daily Peanuts strips were formatted in a four-panel "space saving" format beginning in the 1950s, with a few very rare eight panel strips, that still fit into the four-panel mold. On June 16, 1975, the panel format was shortened slightly horizontally, and shortly after the lettering became larger to accommodate the shrinking format. In 1988, Schulz abandoned this strict format and started using the entire length of the strip, in part to combat the dwindling size of the comics page, and also to experiment. Most daily Peanuts strips in the 1990s were three-panel strips.

Peanuts 2000s[]

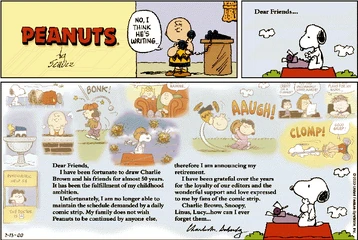

The final original daily Peanuts comic strip was published on January 3, 2000. The strip consisted simply of Snoopy sitting at his typewriter in thought with a note from Schulz that read as follows:

| “ | Dear Friends,

I have been fortunate to draw Charlie Brown and his friends for almost fifty years. It has been the fulfillment of my childhood ambition. Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the schedule demanded by a daily comic strip, My family does not wish Peanuts to be continued by anyone else, therefore I am announcing my retirement. I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to me by fans of the comic strip. Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy...how can I ever forget them... |

” |

The final Peanuts strip (February 13, 2000)

Although the daily strips came to an end, six more original Sunday Peanuts strips had yet to be published. The final original Sunday strip was published in newspapers a day after Schulz's death on February 12. The final Sunday strip included all of the text from the final daily strip, and the only drawing: that of Snoopy typing in the lower right corner. It also added several classic scenes of the Peanuts characters surrounding the text. Following its finish, many newspapers began reprinting older strips under the title Classic Peanuts. Though it no longer maintains the "first billing" in as many newspapers as it enjoyed for much of its original run, Peanuts remains one of the most popular and widely syndicated strips today.

Cast of characters[]

Some well known Peanuts characters. From the left, Franklin, Woodstock, Lucy van Pelt, Snoopy, Linus van Pelt, Charlie Brown, Peppermint Patty and Sally Brown.

The initial cast of Peanuts was small, featuring only Charlie Brown, Shermy, Patty (not to be confused with Peppermint Patty), and a beagle, Snoopy.

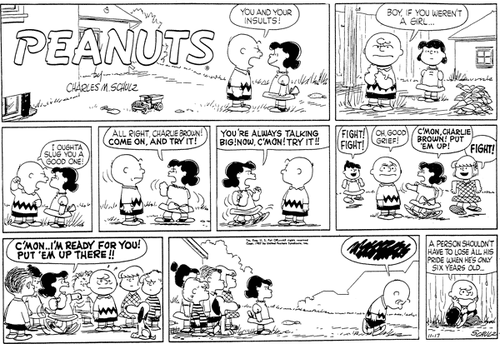

Though the strip did not have a lead character at the onset, it soon began to focus on Charlie Brown, a character developed from some of the painful experiences of Schulz's formative years. Charlie Brown's main characteristic is either self-defeating stubbornness or admirable determined persistence to try his best against all odds: he can never win a ballgame, but continues playing baseball; he can never fly a kite successfully, but continues trying to fly his kite. Though his inferiority complex was evident from the start, in the earliest strips he also got in his own jabs when verbally sparring with Patty and Shermy. Some early strips also involved romantic attractions between Charlie Brown and Patty or Violet (the next major character added to the strip).

As the years went by, Shermy and Patty appeared less often and were demoted to supporting roles, while new major characters were introduced. Schroeder, Lucy, and her brother Linus debuted as very young children — Schroeder and Linus both in diapers and pre-verbal. Snoopy, who began as a more-or-less typical puppy, soon started to verbalize his thoughts via thought bubbles. Eventually he adopted other human characteristics, such as walking on his hind legs, reading books, using a typewriter, and participating in sports. He also grew from being a cute little puppy to a full-grown dog.

In the 1960s, the strip began to focus more on Snoopy. Many of the strips from this point revolve around Snoopy's active, Walter Mitty-like fantasy life, in which he imagined himself to be a World War I Flying Ace or a bestselling suspense novelist, to the bemusement and consternation of the other characters who sometimes wonder what he is doing but also at times participate. Snoopy eventually took on many more distinct personas over the course of the strip, notably college student "Joe Cool".

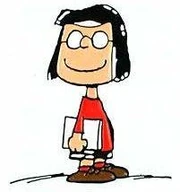

Marcie was introduced to Peanuts in 1971.

Schulz continued to introduce new characters into the strip, including a tomboyish, freckle-faced, shorts-and-sandals-wearing girl named Patricia Reichardt, better known as "Peppermint Patty." "Peppermint" Patty is an assertive, athletic, but rather obtuse girl who shakes up Charlie Brown's world by calling him "Chuck," flirting with him, and giving him compliments he is not sure he deserves. She also brings in a new group of friends, including the strip's first black character, Franklin, and Peppermint Patty's bookish sidekick Marcie, who calls Peppermint Patty "Sir" and Charlie Brown "Charles."

Several additional family members of the characters were also introduced: Charlie Brown's younger sister Sally, who is fixated on Linus; Linus and Lucy's younger brother Rerun; and Spike, Snoopy's desert-dwelling brother from Needles, California, who was apparently named for Schulz's own childhood dog. More of Snoopy's siblings were later introduced into the strip.

Frieda, introduced to Peanuts in 1961.

Other notable characters include: Snoopy's friend Woodstock, a bird whose chirping is represented in print as little black lines but is nevertheless clearly understood by Snoopy; Pig-Pen, the perpetually dirty boy who could raise a cloud of dust on a clean sidewalk or in a snowstorm; and Frieda, a girl proud of her "naturally curly hair", and who owned a cat named Faron, much to Snoopy's chagrin.

Peanuts had several recurring characters who were actually absent from view. Some, such as the Great Pumpkin or the Red Baron, may or may not have been figments of the cast's imaginations. Others were not imaginary, such as the Little Red-Haired Girl (Charlie Brown's perennial dream girl), Joe Shlabotnik (Charlie Brown's baseball hero), World War II a vicious cat who terrifies his neighbor, Snoopy, and Charlie Brown's unnamed pencil pal. After some early anomalies, adult figures never appeared in the strip.

Schulz also added some fantastic elements, sometimes imbuing inanimate objects with sparks of life. Charlie Brown's nemesis, the Kite-Eating Tree, is one example. Sally Brown's school building, that expressed thoughts and feelings about the students (and the general business of being a brick building), is another. Linus' famous "security blanket" also displayed occasional signs of anthropomorphism.

Ages of the Peanuts characters[]

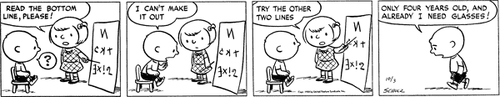

Charlie Brown says that he is four years old in the strip from November 3, 1950.

Over the course of their nearly fifty-year run, most of the characters did not age more than two years. An exception are the characters who were introduced as infants, caught up with the rest of the cast, then stopped. Rerun is unique in that he stopped aging in kindergarten. Linus was first mentioned in the strip as Lucy's baby brother, on September 19, 1952. He aged to around Charlie Brown's age over the course of the first ten years, during which we see him learn to walk and talk with the help of Lucy and Charlie Brown. When Linus stops aging he is about a year or so younger than Charlie Brown. Charlie himself was four when the strip began, and aged over the next two decades until he settled in as an 5-year-old (after which he is consistently referred to as five when any age is given). Sally remains two years younger than her older brother Charlie Brown, although Charlie Brown was already of school age in the strips when she was born and seen as a baby.

In one strip, when Lucy declares that by the time a child is five years old, his personality is already pretty well established, Charlie Brown protests, "But I'm already five! I'm more than five!"

Charlie Brown says that he is six years old in the strip from November 17, 1957.

The characters, however, were not strictly defined by their literal ages. "Were they children or adults? Or some kind of hybrid?" wrote David Michaelis of Time magazine. Schulz distinguished his creations by "fusing adult ideas with a world of small children." Michaelis continues:

“Through his characters, Schulz brought... humor to taboo themes such as faith, intolerance, depression, loneliness, cruelty and despair. His characters were contemplative. They spoke with simplicity and force. They made smart observations about literature, art, classical music, theology, medicine, psychiatry, sports and the law."

In other words, the cast of Peanuts transcended age, and are more broadly human.

Current events were sometimes a subject of the strip over the years. In the November 28, 1995 strip, Sally mentions the Classic Comic Strip Characters series of stamps, which were released four years earlier, and a story about the Vietnam War ran for ten days in the 1960s. The passage of time, however, is negligible and incidental in Peanuts.

Critical acclaim[]

Charles M. Schulz receives his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at Knott's Berry Farm, Buena Park, California in June 1996.

Peanuts is often regarded as one of the most influential and well-written comic strips of all time. Schulz received the National Cartoonist Society Humor Comic Strip Award for Peanuts in 1962, the Elzie Segar Award in 1980, the Reuben Award in 1955 and 1964, and the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999. A Charlie Brown Christmas won a Peabody Award and an Emmy; Peanuts cartoon specials have received a total of two Peabody Awards and four Emmys. For his work on the strip, Charles Schulz is credited with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and a place in the William Randolph Hearst Cartoon Hall of Fame. Peanuts was featured on the cover of Time magazine on April 9, 1965, with the accompanying article praising the strip as being "the leader of a refreshing new breed that takes an unprecedented interest in the basics of life."

Considered amongst the greatest comic strips of all time, Peanuts was declared second in a list of the greatest comics of the 20th century commissioned by The Comics Journal in 1999. Peanuts lost out to George Herriman's Krazy Kat, a strip Schulz himself admired and accepted the positioning in good grace, to the point of agreeing with the result. In 2002 TV Guide declared Snoopy and Charlie Brown equal eighth in their list of "Top 50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All Time", published to commemorate their 50th anniversary.

Cartoon tributes have appeared in other comic strips since Schulz's death in 2000. In May of that year, many cartoonists included a reference to Peanuts in their own strips. Originally planned as a tribute to Schulz's retirement, after his death that February it became a tribute to his life and career. Similarly, on 30 October 2005, several comic strips again included references to Peanuts, and specifically the It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown television special.

A series of statues were erected in St. Paul, Minnesota, Schulz's hometown, which represented a different character each year. The "Peanuts on Parade" tribute began in 2001 with Snoopy statues, followed by Charlie Brown in 2002, Lucy in 2003, Linus in 2004, and Snoopy and Woodstock lying on top of Snoopy's doghouse in 2005.

In 2001, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors renamed the Sonoma County Airport, located a few miles northwest of Santa Rosa, California, the Charles M. Schulz Airport in his honor. The airport's amusing logo features Snoopy in goggles and scarf, taking to the skies on top of his red doghouse. A bronze statue of Charlie Brown and Snoopy stands in Depot Park in downtown Santa Rosa.

Schulz himself was included in the touring exhibition "Masters of American Comics" based on his achievements in the artform whilst producing the strip. His gag work is hailed as being "psychologically complex", and his style on the strip is noted as being "perfectly in keeping with the style of its times."

Television and film productions[]

Peanuts characters in the first Peanuts animated television special, A Charlie Brown Christmas.

In addition to the strip and numerous books, the Peanuts characters have appeared in animated form on television numerous times. This started when the Ford Motor Company licensed the characters in 1959 for a series of black and white television commercials for the Ford Falcon. This deal would expire in 1964. They sometimes appeared in the intro for The Ford Show (1956-1961). The ads were animated by Bill Melendez for Playhouse Pictures, a cartoon studio that had Ford as a client. Schulz and Melendez became friends, and when producer Lee Mendelson decided to make a two-minute animated sequence for a TV documentary called A Boy Named Charlie Brown in 1963, he brought on Melendez for the project. This documentary never aired. The three of them (with help from their sponsor, the Coca-Cola Company) produced their first half-hour animated special, the Emmy- and Peabody Award-winning A Charlie Brown Christmas, which was first aired on the CBS network on 9 December 1965.

The animated version of Peanuts differs in some aspects from the strip. In the strip, adult voices are heard by the characters but conversations are usually only depicted from the children's end. To translate this aspect to the animated medium, Melendez famously used the sound of a trombone with a plunger mute opening and closing on the bell to simulate adult "voices". A more significant deviation from the strip was the treatment of Snoopy. In the strip, the dog's thoughts are verbalized in thought balloons; in animation, he is typically mute, his thoughts communicated through growls, laughs or an un-canine like chirping sound (voiced by Bill Melendez), and pantomime, or by having human characters verbalizing his thoughts for him. These treatments have both been abandoned temporarily in the past. For example, they experimented with teacher dialogue in She's a Good Skate, Charlie Brown. The elimination of Snoopy's "voice" is probably the most controversial aspect of the adaptations, but Schulz apparently approved of the treatment. (Snoopy's thoughts were conveyed in voiceover for the first time in animation in the animated version of the Broadway musical You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and later on occasion in the animated series The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show.)

Melendez had some initial concerns about animating the Peanuts character the way Schulz designed them. They are limited in terms of mobility, for example, arms could only be raised so far. Melendez did not want to compromise the integrity of Schulz's work, and found creative ways of resolving problems presented by their design.

Title card for It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown.

The success of A Charlie Brown Christmas was the impetus for CBS to air many more prime-time Peanuts. specials over the years, beginning with Charlie Brown's All-Stars and It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown in 1966. In total, more than thirty animated specials were produced. Until his death in 1976, jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi composed highly acclaimed musical scores for the specials; in particular, the piece "Linus and Lucy" which has become popularly known as the signature theme song of the Peanuts franchise.

In addition to Coca-Cola, other companies that sponsored Peanuts specials over the years included Dolly Madison cakes, Kellogg's, McDonald's, Peter Paul-Cadbury candy bars, General Mills, and Nabisco.

Schulz, Mendelson, and Melendez also collaborated on four theatrical feature films starring the characters, the first of which was A Boy Named Charlie Brown (1969). Most of these made use of material from Schulz's strips, which were then adapted, even though plots were developed around areas where there were minimal strips to reference. Such was also the case with The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show, a Saturday-morning TV series which debuted on CBS in 1983 and lasted for three seasons.

Happy New Year, Charlie Brown! is an animated TV special based on Peanuts that first aired in 1986.

By the late-1980s, the specials' popularity had begun to wane, and CBS sometimes rejected a few specials. An eight-episode TV miniseries called This is America, Charlie Brown, for instance, was released during a writer's strike. Eventually, the last Peanuts specials were released direct-to-video, and no new ones were created until after the year 2000 when ABC obtained the rights to the three fall holiday specials. The Nickelodeon cable network re-aired the bulk of the specials, as well as The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show, for a time in the late 1990s under the umbrella title You're On Nickelodeon, Charlie Brown. Many of the specials and feature films have also been released on various home video formats over the years.

Eight Peanuts-based specials have been made after Shulz's death. Of these, three are tributes to Peanuts or previous Peanuts animated specials, and five are completely new specials based on dialogue from the strips, and ideas given to ABC by Schulz before his death. He's a Bully, Charlie Brown, was telecast on ABC on November 20, 2006, following a repeat broadcast of A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving. Airing forty-one years after the first special, the premiere of He's a Bully, Charlie Brown was watched by nearly ten million viewers, winning its time slot and beating a Madonna concert special.

Theatrical productions[]

Poster for the 1971 Broadway production of You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown.

The Peanuts characters even found their way to the live stage, appearing in the musicals You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown and Snoopy!!! The Musical, and in Snoopy on Ice, a live Ice Capades-style show aimed primarily at young children, all of which have had several touring productions over the years.

You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown was originally an extremely successful off-Broadway musical that ran for four years (1967-1971) in New York City and on tour, with Gary Burghoff as the original Charlie Brown. An updated revival opened on Broadway in 1999, and by 2002 it had become the most frequently produced musical in American theater history. It was also adapted for television twice, as a live-action NBC special and an animated CBS special.

Snoopy!!! The Musical was a musical comedy based on the Peanuts comic strip, originally performed at Lamb's Theatre off-Broadway in 1982. In its 1983 run in London's West End, it won an Olivier Award. In 1988, it was adapted into an animated TV special. The New Players Theatre in London staged a revival in 2004 to honor its 21st anniversary, but some reviewers noted that its "feel good" sentiments had not aged well.

Record albums[]

Vince Guaraldi.

In 1962, Columbia Records issued an album titled Peanuts, with Kaye Ballard and Arthur Siegel performing (as Lucy and Charlie Brown, respectively) to music composed by Fred Karlin.

Fantasy Records issued several albums featuring Vince Guaraldi's jazz scores from the animated specials, including Jazz Impressions of a Boy Named Charlie Brown (1964), A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965), Oh, Good Grief! (1968), and Charlie Brown's Holiday Hits (1998). All were later reissued on CD.

Other jazz artists have recorded Peanuts-themed albums, often featuring cover versions of Guaraldi's compositions. These include Ellis Marsalis, Jr. and Wynton Marsalis (Joe Cool's Blues, 1995); George Winston (Linus & Lucy, 1996); David Benoit (Here's to You, Charlie Brown!, 2000); and Cyrus Chestnut (A Charlie Brown Christmas, 2000).

Cast recordings (in both original and revival productions) of the stage musicals You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown and Snoopy!!! The Musical have been released over the years.

Numerous animated Peanuts specials were adapted into book-and-record sets, issued on the "Charlie Brown Records" label by Disney Read-Along in the 1970s and '80s.

Other licensed appearances and merchandise[]

Snoopy the World War I Flying Ace on the MetLife blimp.

Over the years, the Peanuts characters have appeared in advertisements for Dolly Madison snack cakes, Friendly's restaurants, A&W Root Beer, Cheerios breakfast cereal, and Ford automobiles. "Pig-Pen" appeared in a memorable spot for Regina vacuum cleaners.

They are currently spokespeople in print and television advertisements for the MetLife insurance company. MetLife usually uses Snoopy in its advertisements as opposed to other characters: for instance, the MetLife blimps are named "Snoopy One" and "Snoopy Two" and feature him in his World War I Flying Ace persona.

The characters have been featured on Hallmark Cards since 1960, and can be found adorning clothing, figurines, plush dolls, flags, balloons, posters, Christmas ornaments, and countless other bits of licensed merchandise.

The Apollo 10 lunar module was nicknamed "Snoopy" and the command module "Charlie Brown". While not included in the official mission logo, Charlie Brown and Snoopy became semi-official mascots for the mission. Schulz also drew some special mission-related artwork for NASA, and at least one regular strip related to the mission, where Charlie Brown consoles Snoopy about how the spacecraft named after him was left in lunar orbit.

The 1960s pop band, The Royal Guardsmen, released several Snoopy-themed albums and singles, including their debut album in 1966 featuring the song "Snoopy vs. the Red Baron", which made it to number two on request charts. The band followed with several other Snoopy-themed songs, but they did not do as well: "The Return of the Red Baron", "Snoopy and His Friends"," Snoopy's Christmas" and "Snoopy for President". Many of these featured cover art by Charles Schulz.

In the 1960s, Robert L. Short interpreted certain themes and conversations in Peanuts as being consistent with parts of Christian theology, and used them as illustrations during his lectures about the gospel, and as source material for several books, as he explained in his bestselling paperback book, The Gospel According to Peanuts.

In 1980, Charles Schulz was introduced to artist Tom Everhart during a collaborative art project. Everhart became fascinated with Schulz's art style and worked Peanuts themed art into his own work. Schulz encouraged Everhart to continue with his work. Everhart continues to be the only artist authorized to paint Peanuts characters.

Giant helium balloons of Charlie Brown and Snoopy have long been a feature in the annual Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City.

The characters were licensed for use in 1992 as atmosphere for the national amusement park chain Cedar Fair.The images of the Peanuts characters are used frequently, most visibly in several versions of the logo for flagship park, Cedar Point. Knott's Berry Farm, which was later acquired by Cedar Fair, was the first theme park to make Snoopy its mascot. Cedar Fair also operated Camp Snoopy, an indoor amusement park in the Mall of America until the mall took over its operation as of March 2005, renaming it The Park at MOA, and no longer using the Peanuts characters as its theme.

The Peanuts characters have been licenced to Universal Studios Japan. Peanuts merchandise in Japan has been licensed by Sanrio, best known for Hello Kitty.

Peanuts characters at the Snoopy's World theme park in New Town Plaza, Sha Tin, Hong Kong.

In New Town Plaza, Sha Tin, Hong Kong, there is a mini theme park dedicated to Snoopy.

The Peanuts gang have also appeared in video games, such as Snoopy in a 1984 by Radarsoft, Snoopy Tennis (Game Boy Color), and in October 2006, Snoopy vs. the Red Baron by Namco Bandai. Many Peanuts characters have cameos in the latter game, including Woodstock, Charlie Brown, Linus, Lucy, Marcie and Sally.

Peanuts has also been involved with NASCAR. In 2000, Jeff Gordon drove his #24 Chevrolet with a Snoopy-themed motif at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Two years later, Tony Stewart drove a #20 Great Pumpkin motif scheme for two races. The first, at Bristol Motor Speedway, featured a black car with Linus sitting in a pumpkin field. Later, at Atlanta Motor Speedway, Tony drove an orange car featuring the Peanuts characters trick-or-treating. Most recently, Bill Elliott drove a #6 Dodge with an A Charlie Brown Christmas scheme. That car ran at the 2005 NASCAR BUSCH Series race at Memphis Motorsports Park..

In April 2002 The Peanuts Collectors Edition Monopoly board was released by USAopoly. The game was created by Justin Gage, a prolific collector and friend of Charles and Jeannie Schulz. The game was dedicated to Schulz in memory of his passing.

When asked whether he felt that licensing threatened to "commercialize" the strip, Schulz said that would be impossible, because comic strips were already a commercial product, designed to sell newspapers. "How can a commercial product be accused of turning commercial?" He also did not feel licensing cheapened the artistic integrity of Peanuts. Comic strips, he said, are not a "pure art form, by any means."

Books[]

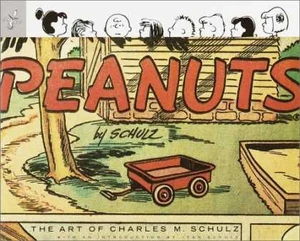

Cover of the 2001 book Peanuts: The Art of Charles Schulz

The Peanuts characters have been featured in many books over the years. Some represented chronological reprints of the newspaper strip, while others were thematic collections, such as Snoopy's Tennis Book. Some single-story books were produced, such as Snoopy and the Red Baron. In addition, most of the animated television specials and feature films were adapted into book form.

Charles Schulz always resisted publication of early Peanuts strips, as they did not reflect the characters as he eventually developed them. However, in 1997 he began talks with Fantagraphics Books to have the entire run of the strip, almost 18,000 cartoons, published chronologically in book form. The first volume in the collection, The Complete Peanuts': 1950 to 1952, was published in April 2004. Peanuts is in a unique situation compared to other comics in that archive quality masters of most strips are still owned by the syndicate. All strips, including Sundays, are in black and white.

The books, like the strips themselves, continue to be issued on an ongoing basis, proof that Peanuts, even after more than sixty years, still continues to resonate with readers of all ages.

External links[]

- Official website.

- Quotations from Peanuts on Wikiquote.

- Peanuts on TV Tropes.

- Peanuts on Facebook.

- Official Peanuts YouTube channel.

- The Complete Peanuts on Internet Archive