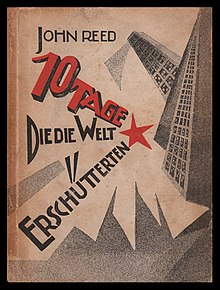

Ten Days That Shook the World

Ten Days That Shook the World (1919) is a book by the American journalist and socialist John Reed. Here, Reed presented a firsthand account of the 1917 Russian October Revolution. Reed followed many of the most prominent Bolsheviks closely during his time in Russia.

Background

John Reed was on an assignment for The Masses, a magazine of socialist politics, when he was reporting on the Russian Revolution. Although Reed stated that he had "tried to see events with the eye of a conscientious reporter, interested in setting down the truth"[1] during the time of the event, he stated in the preface that "in the struggle my sympathies were not neutral"[1] (since the book primarily shares the perspective of the Russian working class).

This book is a slice of intensified history—history as I saw it. It does not pretend to be anything but a detailed account of the November[note 1] Revolution, when the Bolsheviki, at the head of the workers and soldiers, seized the state power of Russia and placed it in the hands of the Soviets.

John Reed[1]

Before John Reed left for Russia, the Espionage Act was passed on June 15, 1917. This provided for fines and imprisonment as a punishment for interference with the recruiting of soldiers and prohibited the mailing of any newspaper or magazine that promoted such sentiments. The US Post Office was also given permission to deny any mailing disqualified by these standards from further postal delivery, and then to disqualify a magazine because it had missed a mailing (owing to the ban) and could therefore be no longer considered a "regular publication".[2] The Masses was thereby forced by the United States federal government to cease publication during the autumn of 1917 after the staff refused to change the magazine's policy against World War I. The Liberator, a magazine founded by Max Eastman and controlled by him and his sister, published Reed's Russian Revolution accounts instead. In an effort to ensure the magazine's survival, Eastman compromised and tempered its views.[3]

Reed returned from Russia during April 1918 via Kristiania in Norway. Since February 23, he had been prohibited from traveling either to America or Russia by the United States Department of State. His trunk of notes and materials about the revolution (which included Russian handbills, newspapers, and written speeches) were seized by custom officials, who interrogated him for four hours over his activities in Russia during the previous eight months. Michael Gold, an eyewitness to Reed's arrival to Manhattan, recalls how "a swarm of Department of Justice men stripped him, went over every inch of his clothes and baggage, and put him through the usual inquisition. Reed had been sick with ptomaine on the boat. The inquisition had also been painful."[4] Back home during mid-summer 1918, Reed, worried that "his vivid impressions on the revolution would fade,"[5] fought to regain his papers from the possession of the government, which long refused to return them.

Reed did not receive his materials until seven months later in November. Max Eastman recalls a meeting with John Reed in the middle of Sheridan Square during the period of time when Reed isolated himself writing the book.

[Reed] wrote it in another ten days and ten nights or little more. He was gaunt, unshaven, greasy-skinned, a stark sleepless half-crazy look on his slightly potato-like face—had come down after a night's work for a cup of coffee.

"Max, don't tell anybody where I am. I'm writing the Russian revolution in a book. I've got all the placards and papers up there in a little room and a Russian dictionary, and I'm working all day and all night. I haven't shut my eyes for thirty-six hours. I'll finish the whole thing in two weeks. And I've got a name for it too—Ten Days that Shook the World. Good-bye, I've got to go get some coffee. Don't for God's sake tell anybody where I am!"

Do you wonder I emphasize his brains? Not so many feats can be found in American literature to surpass what he did there in those two or three weeks in that little room with those piled-up papers in a half-known tongue, piled clear up to the ceiling, and a small dog-eared dictionary, and a memory, and a determination to get it right, and a gorgeous imagination to paint it when he got it. But what I wanted to comment on now was the unqualified, concentrated joy in his mad eyes that morning. He was doing what he was made to do, writing a great book. And he had a name for it too—Ten Days that Shook the World![6]

Critical response

The account has received mixed responses since its publication in 1919, resulting in a wide range of critical reviews ranging negative to positive. It was overall received positively by critics at the time of its first publication despite some critics' opposition to Reed's politics.[7]

George F. Kennan, an American diplomat and historian who was opposed to Bolshevism and is known best as a developer of the idea of "containment" of communism, praised the book. "Reed's account of the events of that time rises above every other contemporary record for its literary power, its penetration, its command of detail" and would be "remembered when all others are forgotten." Kennan considered it as "a reflection of blazing honesty and a purity of idealism that did unintended credit to the American society that produced him, the merits of which he himself understood so poorly."[8] In 1999, The New York Times reported New York University's "Top 100 Works of Journalism", works published in the United States during the 20th century, scored Ten Days that Shook the World as seventh.[9][10] Project director Mitchell Stephens explains the judges' decision:

Perhaps the most controversial work on our list is the seventh, John Reed's book, "Ten Days That Shook the World", reporting on the October revolution in Russia in 1917. Yes, as conservative critics have noted, Reed was a partisan. Yes, historians would do better. But this was probably the most consequential news story of the century, and Reed was there, and Reed could write. The magnitude of the event being reported on and the quality of the writing were other important standards in our considerations.[11]

Not all responses were positive. Joseph Stalin argued in 1924 that Reed was misleading with regard to Leon Trotsky.[12] The book portrays Trotsky (at that time commander of the Red Army) as co-director of the revolution with Vladimir Lenin and mentions Stalin only twice, one of those occasions being in a recitation of names. Russian writer Anatoly Rybakov elaborates on the Stalinist USSR's ban of Ten Days That Shook The World: "The main task was to build a mighty socialist state. For that, mighty power was needed. Stalin was at the head of that power, which means that he stood at its source with Lenin. Together with Lenin he led the October Revolution. John Reed had presented the history of October differently. That wasn't the John Reed we needed."[13] After Stalin's death, the book was allowed to recirculate in the USSR.

This book is a slice of intensified history—history as I saw it. It does not pretend to be anything but a detailed account of the November[note 2] Revolution, when the Bolsheviki, at the head of the workers and soldiers, seized the state power of Russia and placed it in the hands of the Soviets.

John Reed[1]

In contrast to Stalin's objections, Lenin had a different attitude towards the book. At the end of 1919, Lenin had written an introduction for it.[14]

Stalin remained silent on the topic at the time, and only spoke against it after Lenin's death in 1924.[15]

Publication

After its first publication, Reed returned to Russia during the autumn of 1919, delighted to learn that Lenin had taken time to read the book. Furthermore, Lenin agreed to write an introduction that first appeared in the 1922 edition published by Boni & Liveright (New York):[7][16]

With the greatest interest and with never slackening attention I read John Reed's book, Ten Days that Shook the World. Unreservedly do I recommend it to the workers of the world. Here is a book which I should like to see published in millions of copies and translated into all languages. It gives a truthful and most vivid exposition of the events so significant to the comprehension of what really is the Proletarian Revolution and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. These problems are widely discussed, but before one can accept or reject these ideas, he must understand the full significance of his decision. John Reed's book will undoubtedly help to clear this question, which is the fundamental problem of the international labor movement.

V. LENIN.

End of 1919

In his preface to Animal Farm titled "Freedom of the Press" (1945),[17] George Orwell claimed that the British Communist Party published a version which omitted Lenin's introduction and mention of Trotsky.

At the death of John Reed, the author of Ten Days that Shook the World — a first-hand account of the early days of the Russian Revolution — the copyright of the book passed into the hands of the British Communist Party, to whom I believe Reed had bequeathed it. Some years later the British Communists, having destroyed the original edition of the book as completely as they could, issued a garbled version from which they had eliminated mentions of Trotsky and also omitted the introduction written by Lenin.

Aftermath

In the book, Reed refers several times to a planned sequel, titled Kornilov to Brest-Litovsk, which was not finished. In 1920, soon after the completion of the original book, Reed died. He was interred in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow in a site reserved normally only for the most prominent Bolshevik leaders.

Adaptations

Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein filmed the book as October: Ten Days That Shook the World in 1928.

John Reed's own exploits and parts of the book itself were the basis for the 1981 Warren Beatty film Reds, which he directed, co-wrote and featured in. Similarly, the Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Bondarchuk, used it as the basis of his 1982 film Red Bells II. The original Red Bells had covered events earlier in Reed's life.[18]

The British network Granada Television presented a 1967 feature-length documentary. This was narrated by Orson Welles.[19]

"Десять днів, що сколихнули світ" was a 1970 Ukrainian opera Ten Days That Shook the World by Mark Karminskyi.

References in media

Socialist/communist screenwriter Lester Cole referenced the title of the book in his script for the 1946 movie Blood on the Sun, though in a different context. The main characters (played by James Cagney and Sylvia Sidney) plan on spending ten days together, causing one to utter the phrase.

The book is mentioned in the 1981 film Reds which focuses on Reed's life and work.

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d Reed, John (1990) [1919]. Ten Days that Shook the World (1st ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-018293-4.

- ^ Mott, Frank Luther (1941). American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 Years, 1690–1940. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Eastman, Max (1964). Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch. New York: Random House. pp. 69–78.

- ^ Gold, Michael (1940-10-22). "He Loved the People". The New Masses: 8–11.

- ^ Duke, David C. (1987). John Reed. Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 0-8057-7502-1.

- ^ Eastman, Max (1942). Heroes I Have Known: Twelve Who Lived Great Lives. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 223–24.

- ^ a b Duke, David C. (1987). John Reed. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7502-1.

- ^ Kennan, George Frost (1989) [1956]. Russia Leaves the War: Soviet-American Relations, 1917–1920. Princeton University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-691-00841-8.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (1999-03-01). "Journalism's Greatest Hits: Two Lists of a Century's Top Stories". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ "The Top 100 Works of Journalism". New York University. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

- ^ Stephens, Mitchell. "The Top 100 Works of Journalism in the United States in the 20th Century". New York University. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ Trotskyism or Leninism?

- ^ Lehman, Daniel (2002). John Reed & the Writing of Revolution. United States: Ohio University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-8214-1467-4.

- ^ "Lenin: INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK BY JOHN REED: TEN DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD". www.marxists.org.

- ^ "1924: Trotskyism or Leninism?". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ^ "Lenin: INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK BY JOHN REED: TEN DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ^ George Orwell, "The Freedom of the Press, Orwell's Proposed Preface to Animal Farm", online: orwell.ru/library

- ^ Eleanor Mannikka. "Ten Days That Shook the World (1982)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Baseline & All Movie Guide. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Ten Days That Shook the World in the National Library of Australia. (They apparently conflate its date of acquisition with the actual year of production). It's also on YouTube.

External links

- Ten Days that Shook the World at Wikisource

- Ten Days That Shook the World at Standard Ebooks

Ten Days That Shook the World public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ten Days That Shook the World public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Ten Days That Shook the World at Project Gutenberg

- Ten Days That Shook the World at the Internet Archive, a PDF edition of the book published in 1987 by Progress Publishers