Log cabin

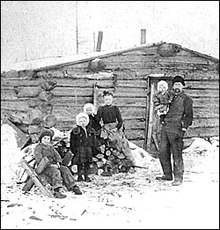

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a minimally finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first-generation home building by settlers.

History

Europe

Construction with logs was described by Roman architect Vitruvius Pollio in his architectural treatise De Architectura. He noted that in Pontus in present-day northeastern Turkey, dwellings were constructed by laying logs horizontally overtop of each other and filling in the gaps with "chips and mud".[1]

Log cabin construction has its roots in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. Although their precise origin is uncertain, the first log structures were probably being built in Northern Europe by the Bronze Age around 3500 BC. C. A. Weslager describes Europeans as having:

The Finns were accomplished in building several forms of log housing, having different methods of corner timbering, and they utilized both round and hewn logs. Their log building had undergone an evolutionary process from the crude "pirtti"... a small gabled-roof cabin of round logs with an opening in the roof to vent smoke, to more sophisticated squared logs with interlocking double-notch joints, the timber extending beyond the corners. Log saunas or bathhouses of this type are still found in rural Finland. By stacking tree trunks one on top of another and overlapping the logs at the corners, people made the "log cabin". They developed interlocking corners by notching the logs at the ends, resulting in strong structures that were easier to make weather-tight by inserting moss or other soft material into the joints. As the original coniferous forest extended over the coldest parts of the world, there was a prime need to keep these cabins warm. The insulating properties of the solid wood were a great advantage over a timber frame construction covered with animal skins, felt, boards or shingles. Over the decades, increasingly complex joints were developed to ensure more weather tight joints between the logs, but the profiles were still largely based on the round log.[2]

A medieval log cabin was considered movable property, evidenced by the relocation of Espåby in 1557, where the buildings were disassembled, transported to a new location, and reassembled. It was also common to replace individual logs damaged by dry rot as necessary.

The Wood Museum in Trondheim, Norway, displays fourteen different traditional profiles, but a basic form of log construction was used all over North Europe and Asia and later imported to America.

Log construction was especially suited to Scandinavia, where straight, tall tree trunks (pine and spruce) are readily available. With suitable tools, a log cabin can be erected from scratch in days by a family. As no chemical reaction is involved, such as hardening of mortar, a log cabin can be erected in any weather or season. Many older towns in Northern Scandinavia have been built exclusively out of log houses, which have been decorated by board paneling and wood cuttings. Today, construction of modern log cabins as leisure homes is a fully developed industry in Finland and Sweden. Modern log cabins often feature fiberglass insulation and are sold as prefabricated kits machined in a factory, rather than hand-built in the field like ancient log cabins.

Log cabins are mostly constructed without the use of nails and thus derive their stability from simple stacking, with only a few dowel joints for reinforcement. This is because a log cabin tends to compress slightly as it settles, over a few months or years. Nails would soon be out of alignment and torn out.

Log cabins were largely built from logs laid horizontally and interlocked on the ends with notches. Some log cabins were built without notches and simply nailed together, but this was not as structurally sound.

The most important aspect of cabin building is the site upon which the cabin was built. Site selection was aimed at providing the cabin inhabitants with both sunlight and drainage to make them better able to cope with the rigors of frontier life. Proper site selection placed the home in a location best suited to manage the farm or ranch. When the first pioneers built cabins, they were able to "cherry pick" the best logs for cabins. These were old-growth trees with few limbs (knots) and straight with little taper. Such logs did not need to be hewn to fit well together. Careful notching minimized the size of the gap between the logs and reduced the amount of chinking (sticks or rocks) or daubing (mud) needed to fill the gap. The length of one log was generally the length of one wall, although this was not a limitation for most good cabin builders.

Decisions had to be made about the type of cabin. Styles varied greatly from one part of North America to another: the size of the cabin, the number of stories, type of roof, the orientation of doors and windows all needed to be taken into account when the cabin was designed. In addition, the source of the logs, the source of stone and available labor, either human or animal, had to be considered. If timber sources were further away from the site, the cabin size might be limited.

Cabin corners were often set on large stones; if the cabin was large, other stones were used at other points along the sill (bottom log). Since they were usually cut into the sill, thresholds were supported with rock as well. These stones are found below the corners of many 18th-century cabins as they are restored. Cabins were set on foundations to keep them out of damp soil but also to allow for storage or basements to be constructed below the cabin. Cabins with earth floors had no need for foundations.

United States and Canada

In North America, cabins were constructed using a variety of notches. One method common in the Ohio River Valley in Southwestern Ohio and Southeastern Indiana is the block house end method, which is exemplified in the David Brown House in Rising Sun, Indiana.

Some older buildings in the Midwestern United States and the Canadian Prairies are log structures covered with clapboards or other materials. 19th-century cabins used as dwellings were occasionally plastered on the interior. The O'Farrell Cabin (c. 1865) in Boise, Idaho, had backed wallpaper used over newspaper. The C.C.A. Christenson Cabin in Ephraim, Utah (c. 1880) was plastered over willow lath. Log cabins reached their peak of complexity and elaboration with the Adirondack-style cabins of the mid-19th century. This style was the inspiration for many United States Park Service lodges built at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century.

Log cabin building never died out or fell out of favor. It was surpassed by the needs of a growing urban United States. During the 1930s and the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration directed the Civilian Conservation Corps to build log lodges throughout the west for use by the Forest Service and the National Park Service. Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood in Oregon was such a log structure, and it was dedicated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1930, the world's largest log cabin was constructed at a private resort in Montebello, Quebec, Canada. Often described as a log château, it serves as the Château Montebello hotel.

The modern version of a log cabin is the log home, which is a house built usually from milled logs. The logs are visible on the exterior and sometimes interior of the house. These cabins are mass manufactured, traditionally in Scandinavian countries and increasingly in Eastern Europe. Squared milled logs are precut for easy assembly. Log homes are popular in rural areas, and even in some suburban locations. In many resort communities in the Western United States, homes of log and stone measuring over 3,000 sq ft (280 m2) are not uncommon. These "kit" log homes are one of the largest consumers of logs in the Western United States.

In the United States, log homes have embodied a traditional approach to home building, one that has resonated throughout American history. Log homes represent a technology that allows a home to be built with a high degree of sustainability. They are frequently considered to be on the leading edge of the green building movement.

Crib barns were a popular type of barn found throughout the American Southern and Southeastern regions. Crib barns were especially ubiquitous in the Appalachian and Ozark Mountain states of North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas. In Europe, modern log cabins are often built in gardens and used as summerhouses, home offices, or as an additional room in the garden. Summer houses and cottages are often built from logs in Northern Europe.

Chinking refers to a broad range of mortar or other infill materials used between the logs in the construction of log cabins and other log-walled structures. Traditionally, dried mosses, such as Pleurozium schreberi or Hylocomium splendens, were used in the Nordic countries as an insulator between logs. In the United States, Chinks were small stones or wood or corn cobs stuffed between the logs.

In the United States, settlers may have first constructed log cabins by 1640. Historians believe that the first log cabins built in North America were in the Swedish colony of New Sweden along the Delaware River and Brandywine River valleys.

Most of the settlers were actually Forest Finns, a heavily oppressed Finnish ethnic group originally from Savonia and Tavastia, who starting from the 1500s were displaced or persuaded to go inhabit and practice slash and burn agriculture (which they were famous for in eastern Finland) in the deep forests of inland Sweden and Norway, during Sweden's 600+ year colonial rule over Finland, who since 1640 were being captured and displaced to the colony.[3]

After arriving, they would escape the Fort Christina center where the Swedes lived, to go and live in the forest as they did back home. They encountered the Lenape Indian tribe, with whom they found many cultural similarities, including slash and burn agriculture, sweat lodges and saunas, and a love of forests, and they ended up living alongside and even culturally assimilating with them[4](they are the earlier and lesser-known Findian tribe,[5][6] being overshadowed by the Ojibwe Findians of Minnesota, Michigan and Ontario, Canada). In those forests, the first log cabins of America were built, using traditional Finnish methods. Even though New Sweden existed only briefly before it was absorbed by the Dutch colony of New Netherland, which was eventually taken over by the English, these quick and easy construction techniques of the Finns not only remained, but spread.[citation needed]

Germans and Ukrainians also used this technique. The contemporaneous British settlers had no tradition of building with logs, but they quickly adopted the method. The first English settlers did not widely use log cabins, building in forms more traditional to them.[7] Few log cabins dating from the 18th century still stand, but they were often not intended as permanent dwellings. Possibly the oldest surviving log house in the United States is the C. A. Nothnagle Log House (c. 1640) in New Jersey. Settlers often built log cabins as temporary homes to live in while constructing larger, permanent houses; then they either demolished the log structures or used them as outbuildings, such as barns or chicken coops.[citation needed]

Log cabins were sometimes hewn on the outside so that siding might be applied; they also might be hewn inside and covered with a variety of materials, ranging from plaster over lath to wallpaper.[citation needed]

Log cabins were constructed with either a purlin roof structure or a rafter roof structure. A purlin roof consists of horizontal logs that are notched into the gable-wall logs. The latter are progressively shortened to form the characteristic triangular gable end. The steepness of the roof was determined by the reduction in size of each gable-wall log as well as the total number of gable-wall logs. Flatter roofed cabins might have had only 2 or 3 gable-wall logs while steeply pitched roofs might have had as many gable-wall logs as a full story. Issues related to eave overhang and a porch also influenced the layout of the cabin.

The decision about roof type often was based on the material for roofing like bark. Milled lumber was usually the most popular choice for rafter roofs in areas where it was available. These roofs typify many log cabins built in the 20th century, having full-cut 2×4 rafters covered with pine and cedar shingles. The purlin roofs found in rural settings and locations, where milled lumber was not available, often were covered with long hand-split shingles.

The log cabin has been a symbol of humble origins in U.S. politics since the early 19th century. At least seven U.S. presidents were born in log cabins, including Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, and James A. Garfield.[8] Although William Henry Harrison was not born in a log cabin, he and the Whigs were among the first to use them during the 1840 presidential election as a symbol to show Americans that he was a man of the people.[9] Other candidates followed Harrison's example, making the idea of a log cabin a recurring theme in U.S. presidential campaigns.[10]

More than a century after Harrison, Adlai Stevenson II said, "I wasn't born in a log cabin. I didn't work my way through school nor did I rise from rags to riches, and there's no use trying to pretend I did."[10] Stevenson lost the 1952 presidential election in a landslide to Dwight D. Eisenhower.

A popular children's toy in the United States is Lincoln Logs, which are various notched dowel rods that can be fitted together to build scale miniature-sized structures.

See also

- Alternative housing

- Blab school

- Burdei

- Cottage

- Izba

- Lincoln Logs

- Log Cabin syrup

- Log house

- Log furniture

- Magoffin County Pioneer Village and Museum

Related housing

References

- ^ Pollio, Vitruvius (1914). Ten Books on Architecture. Harvard University Press. p. 39.

- ^ Weslager, C. A. (1969), The Log Cabin in America, New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, [1]

- ^ Juha Pentikäinen. "Metsäsuomalaisten pitkä matka Savosta Delawaren" (PDF). arkisto.org (in Finnish). Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Rauanheimo 1921. s. 7

- ^ "Findians – The story of Finns' distant cousins | News | Yle Uutiset". 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Findians: A Journey to Distant Cousins". 3 April 2019.

- ^ Bomberger D., "The Preservation and Repair of Historic Log Buildings", National Park Service, 1991. Retrieved 6 December 2008

- ^ "Which US Presidents Lived in a Log Cabin?", WorldAtlas. Retrieved 1 September 2019

- ^ "William Henry Harrison Log Cabin Campaign Souvenir; JQ Adams Signed; "Revolution" in (Campaign) Habits". Shapell Manuscript Foundation. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ a b Lepore, Jill (20 October 2008). "Bound for Glory: Writing Campaign Lives". The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

Further reading

- Aldrich, Chilson D. (1946), The Real Log Cabin, MacMillan.

- Bealer, Alex (1978), The Log Cabin, Crown Publishers, ISBN 0-517-53379-0

- Fickes, Clyde P. & Groben, W. Ellis (2005), Building with Logs & Log Cabin Construction, Almonte, Ontario: Algrove Publishing, ISBN 978-1-897030-22-6.

- Gudmundson, Wayne (1991), Testaments in Wood, St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, ISBN 978-0-87351-268-8.

- Holan, Jerri (1990), Norwegian Wood (First American ed.), New York: Rizzoli, ISBN 978-0-8478-0954-7.

- McRaven, Charles (1994), Building and Restoring the Hewn Log House, Cincinnati: Betterway Books, ISBN 978-1-55870-325-4.

- Phleps, Hermann (1982), The Craft of Log Building, Roger Macgregor, translator, Ottawa, Ontario: Lee Valley Tools, ISBN 978-0-9691019-2-5.

- Weslager, C. A. (1969), The Log Cabin in America, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (February 2021) |

- Log Cabins in America:The Finnish Experience, National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places Lesson Plan

- Log Cabins of Missouri Archived 20 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from the Missouri Folklore Society

- Log Houses of Southern Indiana, by Warren E. Roberts. Indiana University Trickster Press. 1996.

- Short radio episode "Our Redwood Cabin," poem (modeled on "The Old Oaken Bucket") by W.S. Walker from Glimpses of Hungryland, or California Sketches, 1880, from California Legacy Project.

- Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Digital Image Collection at Marquette University; keyword: log cabin.