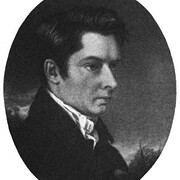

William Hazlitt (1) (1778–1830)

Author of On the Pleasure of Hating

For other authors named William Hazlitt, see the disambiguation page.

About the Author

William Hazlitt was born on April 10, 1778 in Maidstone, England. As a young man, he studied for the ministry at Hackney College in London, but eventually realized that he wasn't committed to becoming a minister. After he lacked success as a portrait painter, he turned to writing. His first book, show more An Essay on the Principles of Human Action, was published in 1805. His other works include Free Thoughts on Public Affairs, Round Table, Table Talk, Spirit of the Age, Characters of Shakespeare, A View of the English Stage, English Poets, English Comic Writers, Political Essays with Sketches of Public Characters, Plain Speaker, and The Life of Napoleon. He died of stomach cancer on September 18, 1830. (Bowker Author Biography) show less

Image credit: engraving by John Hazlitt

Works by William Hazlitt

Lectures on the English poets: The spirit of the age : or, Contemporary portraits (Everyman's library) (1955) 61 copies

Hazlitt on theatre; [selections from the View of the English stage, and Criticisms and dramatic essays] (1991) 15 copies

All That is Worth Remembering: Selected Essays of William Hazlitt (Classic Collection) (2014) 12 copies

Characters of Shakespear's plays : &, Lectures on the English poets / by William Hazlitt (2011) 10 copies

Lectures on the English comic writers,: With miscellaneous essays (Everyman's library. Essays and belles lettres) (1913) 10 copies

The Letters of William Hazlitt (The Gotham library of the New York University Press) (1978) 10 copies

Selected Writings (English Library) — Author — 7 copies

Louis XVII, His Life, His Suffering, His Death: The Captivity of the Royal Family in the Temple (Volumes 1 and 2) (1852) — Editor; Translator — 3 copies

Select British Poets, or new elegant extracts from Chaucer to the present time, with critical remarks. By W. Hazlitt (2011) 2 copies

The Complete Works of William Hazlitt 8. Edited by P. P. Howe, after the edition of A. R. Waller and Arnold Glover (1931) 2 copies

ESSAYS OF WILLIAM HAZLITT 2 copies

Life of Napoleon, 4 vols, D1 2 copies

Selections from William Hazlitt 2 copies

Hazlitt's Wit and Humour 1 copy

Twee essays 1 copy

The Fight and Other Writings — Author — 1 copy

Essays of William Hazlitt 1 copy

The Works of William Hazlitt 1 copy

The fight : an essay 1 copy

This account of the prize fight between Bill Neate and the Gas-Man is extracted from William Hazlitt's essay… (1937) 1 copy

El placer de odiar seguido de Sobre el sentimiento de inmortalidad en la juventud ; Por qué nos gustan los objetos… (2009) 1 copy

Essays and Characters 1 copy

Sketches of the principal picture-galleries in England: with a criticism on "Marriage a-la-mode." (1824) 1 copy

Classic British Literature: 5 books by William Hazlitt in a single file, with active table of contents (2009) 1 copy

Associated Works

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (1589) — Contributor, some editions — 32,525 copies, 169 reviews

The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 4th Edition, Volume 2 (1979) — Contributor — 253 copies, 1 review

Ben Jonson and the Cavalier Poets [Norton Critical Edition] (1975) — Contributor — 235 copies, 2 reviews

Neoclassicism and Romanticism, 1750-1850: Sources and Documents (Sources & Documents in History of Art), Volume 2… (1970) — Contributor — 18 copies

Works of Michael De Montaigne Comprising His Essays, Journey Into Italy, and Letters, with Notes From All the… — some editions — 2 copies

A Reader for Writers — Contributor — 2 copies

Tagged

Common Knowledge

- Birthdate

- 1778-04-10

- Date of death

- 1830-09-18

- Burial location

- St. Anne’s Churchyard, Soho, London, England, UK

- Gender

- male

- Nationality

- UK

- Birthplace

- Maidstone, Kent, England, UK

- Place of death

- Soho, London, England, UK

- Places of residence

- Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Wem, England, UK - Education

- Hackney College

- Occupations

- painter

essayist

journalist

biographer

literary critic

philosopher

Members

Reviews

Lists

Awards

You May Also Like

Associated Authors

Statistics

- Works

- 162

- Also by

- 22

- Members

- 2,425

- Popularity

- #10,578

- Rating

- 4.3

- Reviews

- 16

- ISBNs

- 271

- Languages

- 5

- Favorited

- 16

On the pleasure of hating:

The Fight: p.1-- Do English People ever eat vegetables? I wonder how long they take in the ladies' room? A loathsome subject, so I don't enjoy the story.

On the Spirit of Monarchy: p.47-- Making fun of royalty. "... whatever suffers oppression, They think deserves it.They are ever ready to side with the strong, to insult and trample on the weak." All power is but an unabated nuisance, a barbarous assumption, an aggravated Injustice, that is not directed to the common good: all Grandeur that has not something corresponding to it in personal Merit and heroic acts, is a deliberate burlesque, and an insult on common sense and human nature."

On Reason and Imagination: p. 84--"a spectacle of deliberate cruelty, that shocks everyone that sees and hears of it, is not to be justified by any calculations of cold-blooded self-interest-- is not to be permitted in any case... necessity has been therefore justly called "The tyrant's plea." (Slaughterhouse footage--veganism) There are two classes whom I have found given to this kind of reasoning, against the use of our senses and feelings and what concerns human nature, viz. knaves and fools. The last do it because they think their own shallow Dogma settle all questions best without any farther appeal and the first do it because they know that the refinements of the head are more easily got rid of than the suggestions of the heart and that a strong sense of Injustice, excited by a particular case in all its aggravations, tells more against them than all the distinctions of the jurist.... Thou Hast no speculation in those eyes that thou Dost glare with: thy bones are marrowless, thy blood is cold.

On the Pleasure of Hating: p.104--how long did the Pope, the Bourbons and the Inquisition keep the people of England in breath and Supply them with nicknames to vent their spleen upon? (Trumpudo) .... The pleasure of hating, like a poisonous mineral, eats Into the Heart of religion, and turns it to rankling spleen and bigotry; it makes patriotism an excuse for carrying fire, pestilence, and famine into other lands: it leaves to Virtue nothing but the spirit of censoriousness, and the narrow, jealous, inquisitorial watchfulness over the actions and motives of others..... The only way to be reconciled to Old Friends is to part with them for good: at a distance we may chance to be thrown back(in a waking dream)upon old times and old feelings: or at any rate, we should not think of renewing our intimacy, till we have fairly spit our spite, or said, thought, and felt all the ill we can of each other.(Mary Munro)... I care little what anyone says of me, particularly behind my back, and in the way of critical and analytical discussion - it is looks of dislike and Scorn, that I answered with the worst Venom of my pen. the expression of the face wounds me more than the expression of the tongue.(the Vietnamese women on the next street who follow me to see if my doggies go potty in their yards, despite the fact that I hold up my poo-poo bag for them to see. The next time I'm going to give them a piece of my mind, in Spanish--so there!)... I have seen all that had been done by the mighty yearnings of the spirit and intellect of men, of whom the world was not worthy, and that promised a proud opening to truth and good through the Vista of future years, undone by one man, with just glimmering of understanding enough to feel that he was a king, but not to comprehend how he could be king of a free people! (Obama>Trumpudo)... It has become an understood thing that no one can live by his talents or knowledge who is not ready to prostitute those talents and that knowledge to betray his species, and prey upon his fellow - man.

… (more)