What do you think?

Rate this book

156 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1884

Nature, he used to say, has had her day; she has finally and utterly exhausted the patience of sensitive observers by the revolting uniformity of her landscapes and skyscapes. After all, what platitudinous limitations she imposes, like a tradesman specializing in a single line of business; what petty-minded restrictions, like a shopkeeper stocking one article to the exclusion of all others; what a monotonous store of meadows and trees, what a commonplace display of mountains and seas!

Looking on the bright side of things, I hope that, one fine day, he'll kill the gentlemen who turns up unexpectedly just as he's breaking open his desk. On that day my object will be achieved: I shall have contributed, to the best of my ability, to the making of a scoundrel, one enemy the more for the hideous society which is bleeding us white.That's Des Esseintes for you, speaking of a boy-child he had granted three months of bi-weekly brothel visits to, for no other reason but a sudden whim to conduct a viciously abhorrent sort of social experiment. He doesn't get any better through the course of the book; he is as capable of dwelling on the most beautiful of conjectures in full possession of his educated faculties, as he is of condemning the smallest aspect of life with all the spite and bigotry a human could possibly muster.

He wanted, in short, a work of art both for what it was in itself and for what it allowed him to bestow on it; he wanted to go along with it and on it, as if supported by a friend or carried by a vehicle, into a sphere where sublimated sensations would arouse within him an unexpected commotion, the causes of which he would strive to patiently and even vainly to analyse.He'll pursue this ideal through sight in painting and horticulture, through taste in mouth organs and strenuous dilutions, through smell in perfumes and twisted senses, from the most ancient annals of religion to the newest source of physical debauchery that only those with a sensibility honed by years of monetary excess can hope to afford. That unwholesome mix of artificiality posing as the real thing is fully expressed in the prose itself, metaphors that don't bother to limit themselves to one side of the equation and fully immerse themselves in delight and disgust.

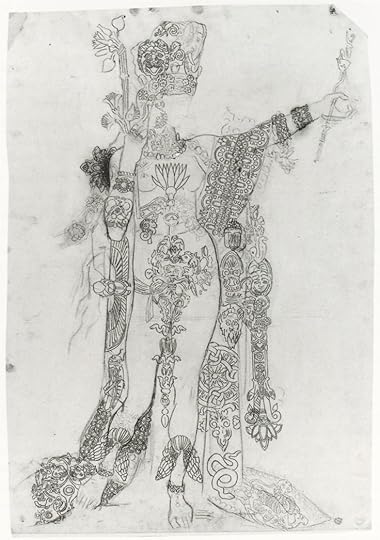

…and the Cypripedium, with its complex, incoherent contours devised by some demented draughtsman. It looked rather like a clog or a tidy, and on top was a human tongue bent back with the string stretched tight, just as you may see it depicted in the plates of medical works dealing with diseases of the throat and mouth; two little wings, of a jujube red, which might almost have been borrowed from a child’s toy windmill, completed this baroque combination of the underside of a tongue, the colour of wine lees and slate, and a glossy pocket-case with a lining that oozed drops of viscous paste.Oftentimes, he'll box himself up in snooty prejudices and hypocritical ideologies, but occasionally one will recognize measures of contemporary thought within his reminisces and desires, one of the most surprising instances occurring when he dwells upon the issue of abortion. At other times he will think on qualities of pieces that at his point in time had not yet been composed, accrediting his thoughts that those who concern themselves with certain ideals will not find themselves content with the current age.

Sensitive to the remotest affinities, he would often use a term that by analogy suggested at once form, scent, colour, quality, and brilliance, to indicate a creature or thing to which he would have had to attach a host of different epithets in order to bring out all its various aspects and qualities, if it had merely been referred to by its technical name. By this means he managed to do away with the formal statement of a comparison that the reader’s mind made by itself as soon as it had understood the symbol, and he avoided dispersing the reader’s attention over all the several qualities that a row of adjectives would have presented one by one, concentrated it instead on a single word, a single entity, producing, as in the case of a picture, a unique and comprehensive impression, an overall view.He may have enjoyed the works of Faulkner, whose The Sound and the Fury accomplishes just that. Or he may have spurned the work that occupies itself with trivial mundanities and contains not the slightest hint of elevated passions or feverish splendor. The world will never know.

Cette promiscuité dans l’admiration était d’ailleurs l’un des plus grands chagrins de sa vie ; d’incompréhensibles succès lui avaient à jamais gâté des tableaux et des livres jadis chers ; devant l’approbation des suffrages, il finissait par leur découvrir d’imperceptibles tares, et il les rejetait….

[This promiscuity of admiration was one of the most distressing things in his life. Incomprehensible successes had permanently ruined books and paintings for him which he had previously held dear; faced with widespread public approbation, he ended up discovering imperceptible flaws in works, and rejecting them….]

célèbre parmi les filles qui se complaisaient à tremper leur nudité dans ce bain d’incarnat tiède qu’aromatisait l’odeur de menthe dégagée par le bois des meubles.

[famous among the girls who had been pleased to soak their nudity in this bath of warm carnation infused by the smell of mint given off by the furniture.]

verbes aux sucs épurés, de substantifs sentant l’encens, d’adjectifs bizarres, taillés grossièrement dans l’or, avec le goût barbare et charmant des bijoux goths….

[purified verb extracts, nouns that reek of incense, bizarre adjectives rough-hewn from gold, with the barbaric, charming appeal of Gothic jewels….]

Last but not least, he hated with all the hatred that was in him the rising generation, the appalling boors who find it necessary to talk and laugh at the top of their voices in restaurants and cafés, who jostle you in the street without a word of apology and who, without expressing or even indicating regret, drive the wheels of a baby-carriage into your legs.

‘the fact is that, pain being one of the consequences of education, in that it grows greater and sharper with the growth of ideas, it follows that the more we try to polish the minds and refine the nervous systems of the under-privileged, the more we shall be developing in their hearts the atrociously active germs of hatred and moral suffering.’

‘Seeing that nowadays there is nothing wholesome left in this world of ours; seeing that the wine we drink and the freedom we enjoy are equally adulterate and derisory; and finally, seeing that it takes a considerable degree of goodwill to believe that the governing classes are worthy of respect and that the lower classes are worthy of help or pity, it seems to me,’

In a period when literature attributed man’s unhappiness almost exclusively to the misfortunes of unrequited love or the jealousies engendered by adulterous love, he had ignored these childish ailments and sounded instead those deeper, deadlier, longer-lasting wounds that are inflicted by satiety, disillusion and contempt upon souls tortured by the present, disgusted by the past, terrified and dismayed by the future.

Faced with the savage fury of these vicious brats, he reflected on the cruel and abominable law of the struggle for life, and contemptible though these children were, he could not help feeling sorry for them and thinking it would have been better for them if their mothers had never borne them. After all, what did their lives amount to but impetigo, colic, fevers, measles, smacks and slaps in childhood; degrading jobs with plenty of kicks and curses at thirteen or so; deceiving mistresses, foul diseases and unfaithful wives in manhood; and then, in old age, infirmities and death-agonies in workhouses or hospitals?