What do you think?

Rate this book

247 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1861

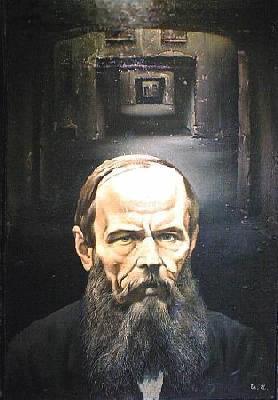

Our prison was at the far end of the citadel behind the ramparts. Peering through the crevices in the palisade in the hope of glimpsing something, one sees nothing but a little corner of the sky, and a high earthwork covered with the long grass of the steppe. Night and day sentries walk to and fro upon it. Then one suddenly realizes that whole years will pass during which one will see, through those same crevices in the palisade, the same sentinels pacing the same earthwork, and the same little corner of the sky, not just above the prison, but far and far away.

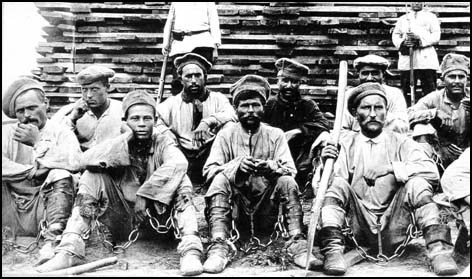

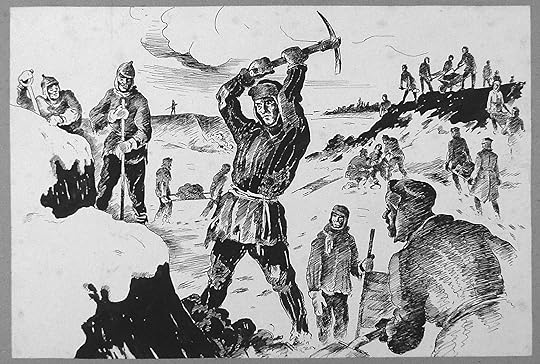

The criminals most cruelly whipped, and who were celebrated as first-rate villains, enjoyed more respect and attention than a simple deserter, a mere recruit, like the one who had just been brought in. But in neither case was any particular sympathy manifested, nor were any annoying remarks made. The unhappy man was attended to in silence, above all if he was incapable of attending to himself. The assistant-surgeon knew that they were entrusting their patients to skilful and experienced hands. The usual treatment consisted in frequent application to the poor fellow’s back of a shirt or piece of linen steeped in cold water. It was also necessary to extract from his wounds the splinters of the rods which had been broken on his back. This last operation was particularly painful to the victims, and the extraordinary stoicism with which they supported their sufferings astonished me greatly.

‘Dead House is journalism, really, but it couldn’t be called that at the time so it’s framed as a novel. It’s part of a genre called Zapiski, which means ‘notes’ or ‘scribbles’. It’s nominally about a third person, but it’s obviously heavily influenced by his experience in prison. I don’t think you could have later writers like Solzhenitsyn without this book.’

‘...the strongest pain may not be in the wounds, but in knowing for certain that in an hour, then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, then now, this second – your soul will fly out of your body and you’ll no longer be a man, and its’ for certain – the main thing is that it’s for certain.’

‘Jails and prisons are designed to break human beings…Prison abolition requires that we challenge our thinking about what constitutes punishment, for whom and why.’

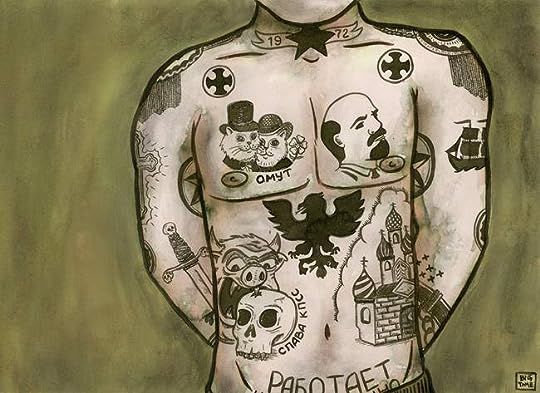

‘In the criminal himself, prison and the most intense forced labor develop only hatred, a thirst for forbidden pleasures, and a terrible light-mindedness. But I am firmly convinced that the famous system of solitary confinement also achieves only a false, deceptive, external purpose. It sucks the living juice from a man, enervates his soul, weakens it, frightens it, and then presents this morally dried-up, half crazed mummy as an example of correction and repentance. Of course, a criminal who has risen against society hates it, and almost always considers himself right and society wrong.’

‘‘if they wanted to crush, to annihilate a man totally, to punish him with the most terrible punishment, so that the most dreadful murderer would shudder at this punishment and be frightened of it beforehand, they would only need to give the labor a character of complete, total uselessness and meaninglessness.’

‘So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilisation, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine, with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age — the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of woman by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night — are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.’

و من المؤكد أن المجرم لا تصلحه سجون و لا معتقلات و لا أشغال شاقة. فهذه العقوبات لا تستطيع إلا أن توقع به القصاص و أن تسكن روع المجتمع من الجرائم التي يمكن أن يرتكبها. و ليس في وسع الإعتقالات و الأشغال المرهقة إلا أن تفاقم في هؤلاء الرجال الحقد العميق. و العطش إلى اللذات المحرمة و الاستهتار الفظيع. و من جهة ثانية. أنا على يقين من أن النظام الشهير للسجن الانفرادي لا يحقق سوى غرض ظاهري و خادع. فهو يبتز من المجرم كل قوته و طاقته. و يثير حفيظة نفسه. فيضعفها و يخيفها. و أخيرا يخرج مومياء جافة و شبه مجنونة كمثال على الإصلاح و التوبة.بالرغم من أن دوستويفسكي يحاول الإيهام بأنها مذكرات شخص أخر إلا أنها تفوح بر��ئحة معاناته و عذابا��ه و تجربته الأليمة في معتقل سيبريا الرهيب.

فالإنسان مهما يصغر شأنه و مهما يهبط قدره و مهما تهن قيمته. يحب بغريزته أن تحترم كرامته من حيث هو إنسان. ان كل سجين يعرف حق المعرفة أنه سجين و يعرف حق المعرفة أنه منبوذ ممقوت مكروه. و يعرف المسافة التي تفصل بينه و بين رؤسائه. و لكن لا القضبان و لا الأغلال تنسيه أنه إنسان. فلابد أن يعامل إذا معاملة إنسانية.لا يشعر بقيمة الكرامة إلا من أُهدرت كرامته و ذاق ويلات المعاناة و الحاجة. و كانت لهذه الصرخة أصداء آتت ثمارها في المجتمع الروسي بعد ذلك و أدت إلى إصلاح حال السجون بصوركبيرة.

أعت��د انه ما من بائعة و ما من ساكنة من ساكنات المدينة بأسرها إلا و أرسلت شيئا إلى السجناء التعساء من أجل المباركة بالعيد. كان بين هذه الصدقات صدقات ثمينة: عدد كبير من أرغفة الخبز المصنوع من فاخر الدقيق. و كان بينها أيضا صدقات زهيدة: رغيف من خبز أبيض ثمنه كوبكان. أو رغيفان من خبز أسود دهن بالقشدة. تلك هدية الفقير للفقير أنفق فيها الأول أخر كوبك يملكه. و كانت هذه الصدقات تقبل بامتنان واحد. دون تفريق بينها في القيمة أو في المصدر. و كان السجناء الذين يستلمون الهدايا يرفعون قبعاتهم عرفانا بالجميل. و يشكرون لأصحاب الهدايا هداياهم و هم يحيونهم و يتمنون لهم عيدا سعيدا ثم ينفقون الصدقات إلى المطبخ.و كما كتب عن روح القانون فإنه لم ينس احسان المحسنين في ذلك الزمن الذي عرف معنى التكافل على أوسع نطاق في سائر أصقاع الأرض.

إن هؤلاء العجزة المسئولين عن تطبيق القانون لا يدركون أبدا أن تطبيق نصوص القانون بغير فهم لروح القانون يؤدي إلى الاضطرابات رأسا. إنهم يقولون: ذلك ما ينص عليه القانون. فماذا تريدون زيادة على ذلك؟ حتى لقد يدهشهم حقا أن تطلب منهم عدا تنفيذ القانون أن يكون لهم شيء من صدق الإحساس و سلامة التفكير. و سلامة التفكير هذه هي التي تبدو لهم زائدة لا محل لها بوجه خاص. فهي في نظرهم ترف لا لزوم له. ترف يثير موجدتهم و يوقظ حنقهم و يعزز تعصبهم.و كتب أيضا عن معاناة السجين في عد الأيام و انتظار يوم الخلاص.

أنتظر صابرا. و أعد الأيام يوما يوما. و يفرحني حتى حين يكون قد بقي عليّ أن أمكث في السجن ألف يوم أخرى. أنني أستطيع أن أقول لنفسي في الغداة أنه لم يبق إلا تسعمائة و تسعة و تسعون يوما. لا ألف يوم.و ما أن يأتي شيئا من خارج السجن حتى يلون الحياة و يعيد الأمل في يوم يستطيع فيه السجين أن يتلمس طريقه مرة أخرى وسط البشر كواحد منهم لا كمنبوذ و مرمي في العراء. مهما كان هذا الشيء صغيرا فسيُحدث الأثر نفسه حتى و لو كان عددا من مجلة.

كنت أستعرض حياتي السابقة و أحلل أدق تفاصيلها. و أطيل التفكير فيها. و أحكم على نفسي بغير رحمة و لا شفقة. كنت أفكر و أقرر و أحلف ألا أقارف في المستقبل ما قارفت في الماضي من أخطاء. و أن أتجنب السقطات التي حطمتني. كنت أنتظر حريتي و أناديها في حرارة و حماسة. كنت أريد أن أجرب قواي مرة أخرى في كفاح جديد.

إن ذلك العدد من المجلة قد بدا لي كأنه رسول قد هبط علي من العالم الأخر. ارتسمت حياتي الماضية أمام عيني بارزة واضحة حينذاك. و حاولت أن أعرف هل أنا تخلفت و هل عاشوا كثيرا بدوني؟ تساءلت عما يشغل بالهم و يحرك نفوسهم. تساءلت عن المسائل التي أصبحت تعنيهم و عن المشكلات التي أصبحت تهمهم. كنت أتلبث على الكلمات قلقا و أقرأ بين السطور و أحاول أن أفهم من العبارات معناها الخفي. و أن أرى ما فيها من إشارات على الماضي الذي أعرفه. كنت أقتفي أثار الأشياء التي كانت تهز الإنفعال في زماني فما كان أشد حزني حين اضطررت أن أعترف لنفسي بأنني أصبحت غريبا عن الحياة الجديدة. و أنني الأن عضو في المجتمع منفصل عنه منبوذ منه. لقد تأخرت و تخلفت.و أخيرا ...

سقطت الأغلال .. أنهضتها .. كنت أريد أن أمسكها في يدي. و أن أنظر غليها مرة أخرى .... أدهشني أنها كانت منذ لحظة تكبل ساقيّ.

وداعا .. إلى الحرية .. إلى الحياة الجديدة .. إلى الانبعاث من بين الأموات.

"كنت أشعر في هذه الأيام بضيق شديد فتناولت كتاب "ذكريات من منزل الأموات" فأعدت قراءته. كنت قد نسيت كثيرًا منه، فلما أعدت قراءته أيقنت أن ليس في الأدب الجديد كله كتاب واحد يفوقه، حتى ولا كُتب بوشكين

ليست النبرة هي الشيء الرائع فيه، بل وجهة النظر التي يشتمل عليها؛ إنه صادق طبيعي مسيحي، إنه كتاب يعلّم الدين

فإذا رأيت دوستويفسكي فقل له أني أحبه"