Rahiolisaurus

| Rahiolisaurus Temporal range:

Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

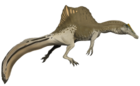

| Life restoration of Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Abelisauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Carnotaurinae |

| Genus: | †Rahiolisaurus Novas et al., 2010 |

| Species: | †R. gujaratensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis | |

Rahiolisaurus is a genus of abelisaurid theropod dinosaur which existed in India during the Late Cretaceous period. It was described in 2010, based on fossils recovered from the Lameta Formation in the Indian state of Gujarat. These fossils include elements from at least seven different individuals and are believed to have been from the Maastrichtian stage, sometime between 70 and 66 million years ago, making it one of the last non-avian dinosaurs known in the fossil record. Despite representing a variety of different growth stages, all recovered fossils from the locality indicate a single species, the type species Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis.

Discovery and naming

[edit]During two expeditions, one in 1995 and the other in 1997, numerous remains of abelisaurids were recovered from a single quarry 50 square metres in area. The collected remains included cervical, dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, portions of pectoral and pelvic girdles, and several hind limb bones. Because of the unearthing of seven differently sized right tibiae, it was suggested that the assemblage was formed by at least seven individuals of different ontogenetic stages. Within the collection were several duplicate bones, such as the ilia, pubes, femora and tibiae, that exhibited similar morphological features of typical abelisauroid traits. However, despite these remains being of different size gradation and representing growth series, hardly any taxonomic variation was discovered. It was interpreted by Novas et al. that the entire theropod collection from this quarry may be referred to the single species Rahiolisaurus.[1]

Individual bones of the newly discovered abelisaurid was given separate catalogue numbers. The holotype of Rahiolisaurus is represented by a partial association of pelvic elements and a femur that were found in the field. It consists of a right ilium (ISIR 550), a right pubis (ISIR 554), and a right femur (ISIR 557). In addition, an axis (ISIR 658) was found in articulation with cervicals 3 (ISIR 659) and 4 (ISIR 660) and are attributed to the species. These bones are currently housed at the collection of the Geology Museum, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata.[1]

Rahiolisaurus was named after the village of Rahioli, located near the fossil site where the dinosaurs remains were discovered. The specific name, gujaratensis, means "from Gujarat" in Latin.[1]

Description

[edit]

Rahiolisaurus was initially described as a large-sized abelisaurid and around 8 metres (26 ft) long and weighing 2 metric tons (2.2 short tons),[1][2] but the allometry-based estimate for different specimens suggest a shorter body length of 6.22–6.75 metres (20.4–22.1 ft).[3] It shares many similarities with another Indian abelisaurid, Rajasaurus, but includes differences such as an overall more gracile and slender-limbed form.[1] Abelisaurids typically had four fingers, short arms, and, to compensate, a heavily constructed head which was the primary tool for hunting; however, the skull was short, they probably had modest jaw musculature, and the teeth were short.[2] Abelisaurids likely had a bite force similar to Allosaurus at around 3,500 newtons (790 lbf).[4]

Classification

[edit]In 2014, the subfamily Majungasaurinae was erected by palaeontologist Thierry Tortosa to separate the newly discovered European Arcovenator, Majungasaurus, Indosaurus, Rahiolisaurus, and Rajasaurus from South American abelisaurids based on physical characteristics such as elongated antorbital fenestrae in front of the eye sockets, and a sagittal crest that widens into a triangular surface towards the front of the head. In more recent analyses Rahiolisaurus as appeared as being more closely related to the South American abelisaurids, further strengthening the faunal similarities between India and South America in the mesozoic.

The following cladogram was recovered by Tortosa (2014):[5]

A phylogeny from 2018 recovered Rahiolisaurus as forming a clade with the Madagascan abelisaurid Dahalokely within majungasaurinae.[6] Only the phylogenies for Abelisauridae is depicted here.

In 2021, Rahiolisaurus and Dahalokely were again recovered as sister taxa, however they were placed outside of majungasaurinae as basal brachyrostrans.[7]

Palaeoecology

[edit]

Rahiolisaurus has been found in the Lameta Formation, a rock unit radiometrically dated to the Maastrichtian age of the latest Cretaceous representing an arid or semi-arid landscape with a river flowing through it–probably providing shrub cover near the water–which formed between episodes of volcanism in the Deccan Traps.[8][9] Rahiolisaurus likely inhabited what is now the Narmada River Valley. The formation is known for being a sauropod nesting site, yielding several dinosaur eggs, and sauropod herds likely chose sandy soil for nesting;[10] though eggs belonging to large theropods have been found, it is unknown if they belong to Rahiolisaurus.[11] Sauropod coprolite remains indicate they lived in a forested landscape, consuming plants such as Podocarpus, Araucaria, and Cheirolepidiaceae conifers; cycads; palm trees; early grass; and Caryophyllaceae, Sapindaceae, and Acanthaceae flowering plants.[12]

Several dinosaurs have been described from the Lameta Formation, such as the noasaurid Laevisuchus; abelisaurids Indosaurus, Indosuchus, Lametasaurus, and Rajasaurus; and the titanosaurian sauropods Jainosaurus, Titanosaurus, and Isisaurus. The diversity of abelisauroid and titanosaurian dinosaurs in Cretaceous India indicates they shared close affinities to the dinosaur life of the other Gondwanan continents, which had similar inhabitants.[13] Dinosaurs in India probably went extinct due to volcanic activity around 350,000 years before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. They likely avoided areas with volcanic fissure vents and lava flows.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Novas, Fernando E., Chatterjee, Sankar, Rudra, Dhiraj K., Datta, P.M. (2010). "Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis, n. gen. n. sp., A New Abelisaurid Theropod from the Late Cretaceous of India" in: Saswati Bandyopadhyay (ed.): New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. pp. 45–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10311-7. ISBN 978-3-642-10310-0.

- ^ a b Paul, G. S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. Bibcode:2017CrRes..69...71G. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Delcourt, R. (2018). "Ceratosaur Palaeobiology: New Insights on Evolution and Ecology of the Southern Rulers". Scientific Reports. 8 (9730): 9730. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.9730D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28154-x. PMC 6021374. PMID 29950661.

- ^ Tortosa, T.; Buffetaut, E.; Vialle, N.; Dutour, Y.; Turini, E.; Cheylan, G. (2014). "A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 100 (1): 63–86. Bibcode:2014AnPal.100...63T. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.10.003.

- ^ Delcourt, Rafael (June 2018). "Ceratosaur palaeobiology: New insights on evolution and ecology of the southern rulers". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). Archived from the original on 9 November 2022 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Gianechini, Federico A.; Méndez, Ariel H.; Filippi, Leonardo S.; Paulina-Carabajal, Ariana; Juárez-Valieri, Rubén D.; Garrido, Alberto C. (10 December 2020). "A new furileusaurian abelisaurid from La Invernada (Upper Cretaceous, Santonian, Bajo de la Carpa Formation), northern Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1877151. Bibcode:2020JVPal..40E7151G. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1877151. ISSN 0272-4634. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Brookfield, M. E.; Sanhi, A. (1987). "Palaeoenvironments of the Lameta beds (late Cretaceous) at Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India: Soils and biotas of a semi-arid alluvial plain". Cretaceous Research. 8 (1): 1–14. Bibcode:1987CrRes...8....1B. doi:10.1016/0195-6671(87)90008-5.

- ^ Mohabey, D. M. (1996). "Depositional environment of Lameta Formation (late Cretaceous) of Nand-Dongargaon inland basin, Maharashtra: the fossil and lithological evidences". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. 37: 1–36.

- ^ Tandon, S. K.; Sood, A.; Andrews, J. E.; Dennis, P. F. (1995). "Palaeoenvironments of the dinosaur-bearing Lameta Beds (Maastrichtian), Narmada Valley, Central India" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 117 (3–4): 153–184. Bibcode:1995PPP...117..153T. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00128-U.

- ^ Lovgren, S. (13 August 2003). "New Dinosaur Species Found in India". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 11 December 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ Sonkusare, H.; Samant, B.; Mohabey, D. M. (2017). "Microflora from Sauropod Coprolites and Associated Sedimentsof Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of Nand-Dongargaon Basin, Maharashtra". Geological Society of India. 89 (4): 391–397. Bibcode:2017JGSI...89..391S. doi:10.1007/s12594-017-0620-0. S2CID 135418472.

- ^ Weishampel, D. B.; Barrett, P. M.; Coria, R.; Le Loeuff, J.; Xijin, Z.; Xing, X.; Sahni, A.; Gomani, E. M. P.; Noto, C. R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 595. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Mohabey, D. M.; Samant, B. (2013). "Deccan continental flood basalt eruption terminated Indian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary". Geological Society of India Special Publication (1): 260–267.