Vhaeraun (pronounced: /veɪˈrɔːn/ vay-RAWN[5][31]), also called the Masked Lord, the Masked God of Night, The Shadow,[5] and, less frequently, the Shadow Lord,[6] the Masked Mage and the Lord of Shadow was the drow god of drow males, thievery, territory, shadow magic, spellfilchers,[2] and evil activities on the surface, aimed to further drow goals, interests, and power there.[4][1]

Vhaeraun was the son of Araushnee[5] and Corellon Larethian.[32] He held the unique view among drow that males and females were equally valuable[4] and was primarily prayed to by those drow males who sought a better life than slavery under Lolth's matriarchy[30] and who opposed it.[33]

Description[]

As an avatar, Vhaeraun appeared as a normal male drow,[35] handsome with a slim, graceful, and toned physique.[30] He could change his size as he wanted[36] and appeared either with a height of 16 feet (4.9 meters)[30][27] or six feet (1.8 meters).[37] His body was surrounded by shadow that did not just randomly lighten and darken but his body seemingly disappeared when this shadow went over him. By allowing it to swallow him completely, Vhaeraun could conduct a rapid form of teleportation.[38]

It was thought that he never used armor,[30] but he was seen wearing leather armor. He always wore a black[39] (or purple[40]) mask and a long cloak of the same hue. His eyes and/or hair could change color to reflect his emotions (red for anger, gold for triumph, blue for amusement, green for puzzlement and curiosity).[27][30][35][37] His hair's default color was white with red highlight.[39]

When he appeared to Inthracis in 1373 DR, he was missing a hand,[41] though at a later time, he was reported to be holding two weapons, one in each hand.[42]

A legend told among drow, to crush the idea of rebellion against the matriarchy, was that Vhaeraun wore his mask to hide scars inflicted by Lolth for his arrogance. A similar legend was one that told Vhaeraun to be mute because he lost his tongue to Lolth for questioning her.[43] The Masked Lord was seen talking with his mouth though the veracity of the latter legend was unknown.[44][45]

Personality[]

Vhaeraun was an arrogant[46] (at times vain) god and shared the vindictive trait of all drow deities.[37] His arrogance made him believe the drow to be above other races. He also urged every single drow to believe she or he was above other drow. His followers derived the idea of gender equality from this belief of his.[46] He believed that all other races should be subjugated by the drow.[32]

While he was willing to use underhandedness to reach his goals, he didn't tolerate the same being used against him or his people.[4][1]

Despite these harsh traits, he was also willing to cooperate when it came to undermining and fighting his mother, Lolth,[47] and tried to unite the other drow gods against her.[30]

Vhaeraun was actively involved in the lives of his followers.[4][37] Tzirik Jaelre went so far as to describe him as a caring god.[49] Vhaeraun was indeed one who didn't distance himself from the concerns of his followers and answered their pleas about fifteen percent of the time,[27] even in the form of sending divine servants in cases of real need.[1] He also seemed to be protective of his followers and was seen providing protection to those in his vicinity when he could[50] and the means to avert self-sacrifice to those working for him.[51]

He and his followers shared a realistic understanding regarding his strength. He knew that he was too weak to fight his mother directly, so he worked against her in secretive ways,[30][32] directed at increasing his and his people's power and decreasing that of his enemies,[52] starting with passive resistance by teaching ideas that contradicted Lolth's dogma[4] and moving to open action. The Masked Lord was unusual among deities for his readiness to enter the front line himself when the scale was right, meaning when the target was another god.[53][54][55]

Like Kiaransalee, Lolth, and Zinzerena, Vhaeraun was prayed to on practically every world inhabited by drow[56]—for example, on Oerth[57]—and had a unique aspect for each world. These aspects were usually different from each other in slight ways,[58] but the one from Toril drastically differed from the other aspects. To be precise, the other aspects were all of a neutral evil god,[26] while the aspect from Toril was chaotic evil.[4]

Powers[]

- Vhaeraun was a lesser deity. He granted spells to his divine spellcasters and gave his clerics access to the abilities and spells of the Chaos, Drow, Evil, Travel, and Trickery domains and could inherently cast the spells from these domains.[59] After the Second Sundering, he granted the new Trickery[60] and War domain to his clerics.[16]

He could look into people's minds. He combined his sensing abilities to be constantly on the look out for dissidents, rebels, and generally dissatisfied people with the potential to work for him against the Spider Queen in Lolth-ruled cities where he had already at least some worshipers working against his mother, like Menzoberranzan, Tlethtyrr, or Waerglarn. Once someone was deemed compatible, the individual was approached by a manifestation of Vhaeraun[52] or sent clerics of his[61] to have a one-on-one inducement interview. (See Manifestations.)

Vhaeraun could speak and read any language, including nonverbal languages,[63] but seemed to have a preference for High Drow.[64] He could transfer information directly into the brains of people with whom he was conversing. This method ensured that the information was transferred without risk of misunderstandings but was very painful for the recipient.[65]

Vhaeraun could levitate.[40] He was one of two creatures who lived on Carceri but didn't really belong there, for he could get in and out of the Red Prison as he wanted. This fact brought them the hatred of other deities from the Tarterian Depths.[66] Out of all his movement abilities, teleportation seemed to come most naturally to him. He was seen casually teleporting around walking distance during his business negotiation with Inthracis.[67] For all these movement abilities, he had his limits. For example, he couldn't ignore Lolth's ban on entering her domain during the Silence of Lolth and needed outside help to do so.[40]

Vhaeraun had the ability to turn his body parts incorporeal and touch corporeal things inside a corporeal container while remaining incorporeal. For example, he could grab inside a body and crush its internal organs.[68] It is not clear whether it was his ability to cast polymorph any object, but he once changed a cage with Sehanine Moonbow inside into portable size and dumped her through a gate that he created.[69]

Apart from always moving as though under pass without trace,[30] the Masked Lord could cast any invisibility spell[37] and turning invisible was a part of his fighting style.[30] What made his abilities at stealth truly special though wasn't the abilities themselves but his skills at them. An entire percent of his clergy in his church consisted of clerical double spies, called masked traitors, clerics whom Lolth believed were under her employment but were in truth specialty priests of her son. This was possible because of his aforementioned skill. Lolth, who was more powerful than him, simply couldn't compete with him on the field of stealth and trickery.[52]

Vhaeraun could change his and his equipment's size[40] and fought as a warrior and as an assassin with two weapons—a longsword, Nightshadow, in his main hand, and a short sword, Shadowflash, in the off-hand.[30] His martial fighting style was of mostly defensive nature and consisted of riposting while primarily dodging and evading enemy blows, parrying only when he had no other choice.[71] It was impossible to hit him with mundane weapons.[30] His prowess in an open, frontal fight wasn't that of a war god. He once fought Selvetarm,[72] the drow demigod of battle prowess,[1] and was driven away, effectively losing against his own son.[72]

Vhaeraun possessed all the immunities and protections of a lesser deity.[73] In addition, Vhaeraun was immune to all kind of illusions—except those created by more powerful divine beings—and to being charmed.[30] While the immunities of deities were generally useless against a divine creature of higher status,[73] when it came to his immunity against charms, he was under no such restrictions.[30]

Vhaeraun was thought to be unable to cast spells by himself;[30] on the other hand, he was called the Masked Mage[2] and was observed making extensive use of spells[72] and Inthracis sensed immense arcane energy from him.[74] He was able to duplicate any divine or arcane spell used by his followers within 180 feet (55 meters) and could cast them while fighting physically at the same time.[30] Duplicating other people's spells was also possible for him. However it had a limit in both strength and frequency. he could do so only six times per day, but he could use the spells of any spellcaster within 120 feet (36 meters).[75] He was capable of generating heat, both in the form of magma[50] and by converting blasts of shadowstuff into fire, the latter being hot enough to cause agony to deities.[76] He could also cause a bladebend effect once every six minutes.[30]

Possessions[]

Normally, deities didn't use magic items,[77] but Vhaeraun could and did wield any magic item provided by his followers, as long as they could be used by evil individuals,[30] and he had a penchant to use protective magic items. He also charged one magic item per calling of his avatar as payment.[78] (See Manifestations.)

In battle, he wielded two swords, Nightshadow and Shadowflash. The former was a black longsword of quickness,[30] which he could make appear out of nowhere in his hands[40] and that was invisible while in darkness.[30]

Shadowflash was a short sword made of silver, which could emit a flash of eerie light, capable of blinding those who looked at it.[30] He also carried a dagger, though its properties were unknown.[79]

The Masked Lord's cloak was able to absorb seven spells of any strength each day, including magic that could affect a whole area, (therefore protecting both the deity and those who stood near him,) and could make the wearer transparent to those who looked through it. If stolen, or when the avatar of its owner was destroyed, the cloak would melt into nothing.[30]

Divine Realm[]

Main article: Ellaniath

Vhaeraun’s home realm was called Ellaniath,[80] the whereabouts of which were unknown as the Masked Lord wiped the memories of any visitor.[81]

Manifestations[]

Vhaeraun had a number of ways to manifest his powers. Apart from his own avatar[30] or his minions' direct help,[1] he could empower[30] and inform his people.[82] He had problems to keep himself from helping his followers, which translated into him answering 15% of the prayers towards him.[27]

Calling[]

- Avatar

Vhaeraun was capable of creating avatars and preferred to appear in his avatar form when possible. (See Description.) A ritual needed to be completed for such an event,[30] but even when said ritual was completed, the avatar appeared only once in five times. On appearing, a magic item needed to be given to (or just taken by) the avatar). If a magic item was not available, the summoner was sent on a quest to get one. The obtained magic item was then offered on an altar, and any thieves who might steal this item were pursued by the avatar.[78]

The ritual consisted of the casting of a gate spell and could be done reliably and without the need to offer a magic item when the Masked Lord's personal goals were involved, if the calling of an avatar as done by Tzirik Jaelre was taken as a standard.[44]

- Servitors

It was relatively easy to convince Vhaeraun to send one of his servitors for help, provided the proper rituals were conducted in situations of real need.[1] "Real need" didn't necessarily mean life or death situations. Instances in which shadows were used as messengers to contact a large number of followers in a wide area were known.[83]

Tangible Effects[]

Apart from direct help, Vhaeraun had other means by which he could provide his followers with tangible help.

- Flitting Black Shadow

When Vhaeraun wanted to directly help an individual who hadn't conducted the ritual to call his avatar, he could send a flitting black shadow. It acted as a half-mask for a chosen individual for about nine minutes.[30]

During that time, the recipient received a blessing in the form of minor healing, the true seeing spell, ability to wound creatures immune to mundane weapons, moving silently while under the pass without trace spell, and success at keeping one's footing under all circumstances. A single creature could only be blessed like this once per day.[30]

- Half-mask of Shadow

Another manifestation consisted of a floating insubstantial half-mask, made of shadow. It could pass through any obstacle, magical or not and including divine boundaries, to reach the enemy of his people. The mask then (twice per appearance) laughed mockingly and chillingly, inducing terror in those who heard it, as though with the fear spell.[30]

- Interview

Vhaeraun could see into other people's minds, he used this ability to discern compatibility with his philosophy. Once a person with the proper mindset was found, a shadowy black face mask appeared before the individual. Via telepathy, a one-on-one inducement talk was conducted. If such a private meeting was discovered, the mask used a number spells to kill the intruders. After proving that his cause was based on power and had chances to succeed, the mask left to come back later for another talk.[84]

Information[]

Vhaeraun could, apart from the standard manifestations (see infobox), convey information by sharing concrete information with several people at once through shared dreams.[85]

Activities[]

Vhaeraun's goal was to put the Ilythiiri,[52] or drow, back into the position of power that they once held. He detested seeing his people wither because of the pointless infighting and division that Lolth promoted. His plan towards his goal was to undo the Spider Queen and her idea of "society", replacing it with one where the drow would be united and both genders treated with equality. He saw that as the only way to lead the drow to reclaim their power and place on the surface, called the Night Above, to rule over all the others.[52][32] Elves represented an exception, as it was Vhaeraun's belief that all the Tel'Quessir needed to work together for common progress.[4][47][27]

Vhaeraun spying on his enemies.

The Masked Lord taught subtle opposition against the priestesses of Lolth and their ideals.[30] He incited his followers to rebel and sow rebellion—especially among male drow—against the Spider Queen's matriarchy, by any means available,[1] going as far as to personally teach methods and skills of resistance.[5]

According to the Mordenkainen, however, after the Second Sundering, Vhaeraun changed his stance, and his faith became mostly practiced by males who wished for a better lot in life, but that weren't willing to rebel against Lolth's matriarchy.[86]

On the surface, Vhaeraun taught his followers to increase drow power and influence based on real assets, by trade and association with other creatures, but also by criminal means,[52] for example thievery.[27] These kind of activities on the surface were so similar to Mask's[30]—whose activities consisted of creating a trustworthy front and not committing unnecessary crimes in the face of other means[87]—that the two deities were confused with each other among non-drow there.[30] After the Second Sundering, Vhaeraun's modus operandi emphasized the "good citizens" part more strongly than before.[88]

The Shadow also gathered any particularly effective poisons, spells, and tactics devised by his clerics, in order to share such tools with the rest,[52][32][27] and also trained the otherwise defenseless male drow in the skills of a rogue.[5]

Relationships[]

Vhaeraun was the son of Corellon Larethian and Lolth,[89] the elder twin[90] brother of Eilistraee.[32] He was the father of Selvetarm.[1] He opposed and was opposed by all of his family members.[4][91]

Seldarine[]

The relationship between him and the Seldarine, of which he was formerly a part, were poor; in fact all members of the Seldarine considered him their enemy.[92]

- Corellon Larethian

After his son Vhaeraun's betrayal during the War of the Seldarine, Corellon practically cut his son off and exiled him.[94]

Corellon gave up on the idea of trying to turn his son Vhaeraun to abandon his ways.[95] He vowed to kill Vhaeraun if he ever tried to hurt his sister.[94] Nevertheless, the Masked Lord did threaten the Dark Maiden's life, without known action against him on Corellon's part.[96]

Interestingly, the one type of magic that the Protector considered too corrupt for elves and thus suitable for drow, the usage of the Shadow Weave,[97] was the niche Vhaeraun filled in his role as the patron of shadow magic.[2]

- Sehanine Moonbow

Vhaeraun hated Sehanine Moonbow for escaping his prison during the War of the Seldarine.[98]

- Shevarash

Shevarash dedicated his life to killing drow. Vhaeraun was his primary target, alongside Lolth.[99] It was unclear why the Black Archer viewed the Masked Lord as a primary enemy, since Vhaeraun also wanted to get rid of the Spider Queen.[100]

- Vandria Gilmadrith

The relationship between Vhaeraun and Vandria Gilmadrith, his full-blooded sibling still among the Seldarine, was unclear.[101]

Dark Seldarine[]

The Dark Seldarine. From left to right: Vhaeraun, Kiaransalee, Lolth, Selvetarm, Ghaunadaur, and Eilistraee.

The relationship between him and the rest of the Dark Seldarine was not good; his relationship with Lolth was completely hostile. One of Vhaeraun's goals was it to unite the rest of the drow powers against the Spider Queen.[30] Such cooperation was difficult, because of the vastly different views each deity shared,[8] though he did succeed at forming an alliance with Kiaransalee[102] with cooperation with both Ghaunadaur and Selvetarm to a lesser extent. (See below.)

- Lolth

Vhaeraun and Lolth's relationship started as mother and son.[32] Vhaeraun shared her trait of ambition and became her confidant in her betrayal against her husband.[103] At latest after the Descent, the two were complete enemies, Vhaeraun calling for the destruction of the society for which she stood.[32]

Vhaeraun was Lolth's favorite child[46] and she encouraged her son's rivalry with her, for it appealed to her love of chaos.[104] On the other hand, her son having actual success at swaying the drow to his cause of destroying her, her supporters and beneficiaries, and her version of society[32] was a real source of fear for her.[105] Lolth viewed him as her true rival[30][34] and enemy, leading to her incorporating specific tenets against her son's followers.[106]

Mother and son had little to no common ground. Lolth promoted favoritism towards females;[107] Vhaeraun promoted gender equality.[32] The Spider Queen demanded surface elves as sacrifices from her worshipers;[108] the Masked Lord urged his followers to cooperate with surface elves.[4] Lolth tried to keep drow society stagnant in every regard;[109] Vhaeraun attracted those who wanted change in societal progress, economic growth, territorial expansion, etc.[34] Lolth wanted to extinguish the drow race's desire to return to the surface;[110][111] Vhaeraun called for settling the surface.[52][32] These differences made the idea of Lolth's forces and those from the surface working together against Vhaeraun's into something not completely impossible.[112]

According to the wizard Mordenkainen, this changed after the Second Sundering. He claimed that Vhaeraun had assumed a position of subservience to the Spider Queen.[86]

- Eilistraee

Vhaeraun hated his sister Eilistraee, and the two were on hostile terms.[98] Vhaeraun's hatred against Eilistraee originated both from his sister having been the favored child of Corellon Larethian and from her hindering his efforts to bring the Ilythiiri under him, (as that conflict opened the way for Lolth and Ghaunadaur to rise to prominence.) Nonetheless, he tried to bring her alongside the other drow gods on his side against Lolth.[98][95]Eilistraee, on the other hand, mourned her brother's selfishness and cruelty. The Dark Maiden opposed her brother's ruthless ways, and she wished to lead the drow along the path of light.[113]. Her divine champions generally chose the evil deities of the Dark Seldarine as enemies to oppose, and that led some of them to focus their efforts against the followers of Vhaeraun.[114] Their enmity continued after the Second Sundering.[3]

They shared a few characteristics. Both wanted their people on the surface—Eilistraee, in harmony with others,[116] Vhaeraun, by building power structures that allowed his followers to rule over others.[52][32]

A slur to describe him among the followers of Eilistraee was the Sly Savage.[117]

- Ghaunadaur

He was opposed to Ghaunadaur.[4] The two gods used to guide the elves of Ilythiir together, during their time there,[118] though it was not clear whether they were on amicable terms. If Ka'Narlist was taken as a measure, followers of Ghaunadaur considered Vhaeraun an upstart who was not attractive to those who were looking for life force as a power source.[119] There was also an overlap in their follower base. A meaningful part of Ghaunadaur's followers were philosophically closer to Vhaeraun than Ghaunadaur and followed the latter only because they didn't know about the god of thievery or his agenda.[120] Followers of Ghaunadaur and Vhaeraun seemed to work together based on individual projects. As examples, followers of the two worked together to destroy the Lolth-worshipers in Eryndlyn.[121] The Ghaunadan fey'ri House Dlardrageth[122] and the Vhaeraunite drow House Jaelre worked together to protect themselves from the Army of Myth Drannor,[123] and even after Vhaeraun's death, a faction of Vhaeraunites and Ghaunadans successfully worked together to destroy the Promenade of the Dark Maiden.[124] They were even capable of living side by side, like in Holldaybim.[125]

- Kiaransalee

Vhaeraun was allied with Kiaransalee, though she was also allied with Lolth.[102] The difference between these two relationships was that the former was a willing alliance to get rid of Lolth's dominance,[1] while the latter took the form of forced subservience to the Spider Queen and included an enmity.[126]

- Selvetarm

Vhaeraun was opposed by his son Selvetarm.[91] For example, when the draegloths started to convert to Vhaeraun during the Silence of Lolth, Selvetarm took some in with the intention of handing them over to his grandmother when she awoke again.[127] Even though Selvetarm hated his grandmother,[128] to whom he was practically enslaved,[1] he still fought against his father during the Silence of Lolth, as Vhaeraun sought to destroy Lolth in her weakened state, thus botching his chance for freedom.[72] Vhaeraun had a very low opinion about Selvetarm's intelligence,[129] but the submissive trait of his son was what angered him most.[130] It seemed that his position as patron of male drow was contended by the more conformist Selvetarm after the Second Sundering.[33] At some point in time, though, the two managed to set aside their differences enough for radical Selvetargtlin and Vhaeraunites to cooperate, such that being raised by Selvetargtlin was not something to bat an eye at.[131]

It was heavily suspected that the reason why the attack on the Promenade of the Dark Maiden and Vhaeraun's assassination attempt on the Dark Maiden were on the same day was because the two gods were in league with each other.[132]

Enemies[]

- Underdark Deities

A large number of Underdark deities were also his enemies. They included the duergar deities Laduguer and Deep Duerra, the derro deities Diirinka and Diinkarazan, the beholder deities Great Mother and Gzemnid, the mind flayer deities Ilsensine and Maanzecorian, the aboleth progenitor Piscaethces, the ixzan deity Ilxendren, the kuo-toa deity Blibdoolpoolp, the myconid deity Psilofyr, and the troglodyte deity Laogzed.[4] This could have been less from personal grudges than from the fact that, in the Underdark, societies organized and identified themselves first through their racial identities and tended to enslave others who were not of the same race to make the generation and distribution of the (extremely) scarce resources easier.[133][134]

- Surface Deities

Other enemies of his were Sharess and the halfling deity Cyrrollalee.[4] Vhaeraun's enmity with Cyrrollalee was rooted in their portfolios. The halfling goddess was the deity of homes and Vhaeraun was the god of thievery and thus an intruder into homes.[135] His enmity with Sharess had a more specific background. (See Age of Humanity.)

Allies[]

Vhaeraun enjoyed a working relationship with Mask, Shar, and Talona.[4][32]

The symbol of Mask, one of Vhaeraun's allies.

The symbol of Vhaeraun.

Vhaeraun was an ally of Mask.[32] The two were similar in many ways,[47] and among non-drow on the surface, the two were often confused with one another.[4] The two even shared one similar title—"Lord of Shadows" for Mask[136] and "Lord of Shadow" for Vhaeraun.[2]

While Mask was interested in absorbing Vhaeraun to compensate his loss of power to Cyric[47], there were also followers of Vhaeraun who used the resemblance of the two gods' symbols and methods to recruit followers among humans and half-elves.[52]

- Shar

Vhaeraun was the drow patron of shadow magic[2] and Shar was the owner of the Shadow Weave.[137] They worked together in projects that concerned this magic, like the School of the Shadow Weave, which had followers of both Vhaeraun[138][139] and Shar among them.[140] When Vhaeraun died, Shar was also one of the prime choices to whom his followers might convert.[141]

- Talona

Talona was a deity from Carceri, which meant that she hated Vhaeraun for being able to go in out of the Red Prison at his leisure, but she found him exceedingly dangerous.[66] Still, the Lady of Poison and the Masked Lord maintained a functional working relationship.[32]

Followers[]

Generally speaking, the evil drow deities had a strange relationship with their followers. In some cases, followers were referred to in terms of belonging to one or the other deity like possessions.[138][142]. That seemed to be meant in the literal sense for Lolth[143] and Kiaransalee,[144] who were capable of using their followers' fate as a wager in their game for their own gain.[145][note 1] While Vhaeraun meddled in this game, he didn't wager his followers like the others.[143]

The drow gods also had dogmas that were generally concerned with describing how to live a life that pleased them,[146] whereas Vhaeraun's dogma was unique in that it was used to outline the goal of his organization and the steps towards it.[32] He considered himself the leader of this endeavor.[32]

The relationship between him and his followers was based on a deal—the followers' obedience in exchange for divine support,[8] whereas piety was at best of secondary concern.[113] His followers joined him for different reasons, from actually agreeing with his philosophy,[52] to more personal reasons like the desire for change[30] or freedom,[61] to completely personal reasons like the desire for revenge, simple madness,[52] or because they thought that Vhaeraun's support was a tool strong enough for the follower's social advancement to justify the risk of exposure.[113]

Vhaeraun primarily valued his followers for their action; what was excluded from evaluation were their intentions, private desires, and thoughts, including rebellious ones. He was capable of punishing his followers for bad performance—a good track record wasn't considered an excuse for it.[147] He also punished for transgressions, such as impersonating him, even with punishments that virtually meant death, as happened to Tellik Melarn.[148] He held people in high standing for their actions, despite any rebellious thoughts against him.[149]

Mortals[]

His goal was to lead the drow back to their former position of power. He saw a general need for advancement for elves and encouraged cooperation, including intermarriage among the elven races. The goal included the subjugation of other races. Intermarrying also had an ulterior motive in the form of increasing drow numbers on the surface by taking advantage of the drow's genetic dominance and the psychological quirk of children to favor their drow parent.[21][52] Despite this, cooperation with other races was possible. He had an unexplained dislike against dwarves and gnomes and forbade his followers from associating with these races,[47][4][27] but they did so anyway. (See Church of Vhaeraun.)

He found halflings and humans tolerable.[4][27] It was believed that the Shadow wanted, or at least was not against, the drow interbreeding with humans to acquire their genetic traits.[150]

Worshipers[]

Main article: Church of Vhaeraun

A priest of Vhaeraun in typical regalia.

Vhaeraun had the largest drow following on the surface[151][47] and the second largest overall.[152] The church of Vhaeraun primarily consisted of drow and half-drow males who sought a better life than slavery under Lolth's matriarchy,[30] and who opposed it.[33] The promise of a gender-fair society[52] in which empathy, cooperation, and growth was possible appealed to them.[34]

The followers of Vhaeraun believed that they must free themselves from the tyranny of the Lolth and take their rightful place in the Night Above by force. This would involve the destruction of the drow matriarchy and the infighting of Lolth's followers, resulting in the unification of the drow people, as opposed to a squabbling collection of rival Houses with conflicting aims. They believed that Vhaeraun would lead them in a society where the drow ruled over all the other, inferior races and where male and female were equals.[32]

Servitors[]

The Masked Lord was personally served by his petitioners, the souls of his dead followers,[153] on his realm Ellaniath.[154] Some petitioners were turned into vhaeraths, petitioners who gained additional abilities in stealth and retained their skills in life, who were frequently dispatched to Toril to do their god's bidding.[29]

Other servitor creatures were gehreleths (farastu, kelubar, and shator); mephits (air, smoke, and earth), shadow dragons, shadow fiends, shadows,[30] and yeth hounds.[155] Petitioners who distinguished themselves in life through great service were turned by the Masked Lord into some type of his servitor creatures.[156]

Vhaeraun once forbade his priests to use spells to summon any servant creatures, as he expected them to only perform rituals to summon his avatar[30] and to show their self-reliance.[157] This rule was substantially relaxed, and it became in fact easy to convince him to send one of his servitors for help, provided the proper ritual was conducted.[1] He also provided his followers access to his servitors for their summon monster and planar ally spells.[158] The vhaeraths were an exception; calling them required the knowledge outlined in the Obsul Ssussun.[29]

Symbol[]

The symbol of Vhaeraun.

Vhaeraun's symbol was a black half-mask.[4] One variation consisted of two black lenses forming a mask.[1] There was also a slight variation of this symbol that consisted of a black mask with two blue lenses.[60]

History[]

The Dawn Age[]

- See also: Dawn Age

Vhaeraun was born as the son of Corellon Larethian and Lolth,[32] as the elder twin brother of Eilistraee,[90] and the brother of Vandria Gilmadrith. About −30,000 DR, Lolth (at that time called Araushnee) tried to overthrow her husband as the head of the elven pantheon.[103][159]

Vhaeraun was her confidant in this betrayal.[4] He was unique in that he didn't feel attachment to membership in the Seldarine, suggesting the option of simply leaving the group, and he also didn't see inherent value in blood ties. What gave Araushnee the final nudge away from the Seldarine was a combination of realizing that she was alone, after understanding her son's capability to betray his father and his potential to murder her later to come out on top.[161]

Eilistraee was intended to be the unknowing murderer of her father[162] and the scapegoat for the betrayal.[90] The plan involved Corellon's sheath, on which a curse was placed. Vhaeraun was the one who hid Corellon's sheath, so that Eilistraee would find it,[69] which she did out of her known affection towards her father.[163] The sheath was cursed to direct her arrows to the bearer, Corellon,[113] and retrieving it and giving it back to him guaranteed that she would be in his vicinity when the battle ensued.[163] Vhaeraun's other role was to imprison Sehanine Moonbow.[98] She needed to be imprisoned because his mother Lolth conducted the very first step of the betrayal in plain sight of the moon goddess, thus revealing it to her.[164] The moon goddess eventually managed to escape her prison, albeit at high cost to herself.[165] During the war, Vhaeraun protected Araushnee.[166] After the war, a trial was called, and Vhaeraun was one of those sent into exile from the Seldarine.[167]

The Time of Dragons[]

During the Time of Dragons, the first elves came to Toril. They didn't know about the Seldarine and mostly strove to live in scattered tribes with one exception, the Ilythiiri.[168] Among them, Vhaeraun became the mainstream deity.[96] in the first elven state Ilythiir.[168]

He, and to a lesser degree Ghaunadaur, helped their people to carefully but successfully expand their territory throughout southern Faerûn[118] (at that time the name for the single continent on Toril)[169] and power, to a level that kept them independent from the dragons.[170] Eilistraee tried to stop Vhaeraun's evil machinations,[171] for which he tried to kill her.[96]

Throughout this time, he maintained thin ties with his mother.[172] Without any evil intentions, the moon elf Kethryllia Amarillis drew Lolth to Toril in −24,400 DR;[169] the Spider Queen then made inroads in the southern state of Ilythiir.[173]

The First Flowering[]

- See also: First Flowering

Vhaeraun became the most popular deity in southern Ilythiir,[174] as that nation spread throughout the south of the continent,[169] with Vhaeraun as the driving force behind this development.[118] This position of hegemony changed with the First Sundering[174] in −17,600 DR.[169]

Despite vastly different views, Ilythiir was originally on good footing with the other elven nations,[175] but Lolth poisoned the relationships between dark elves and other subraces.[176] Seldarine-following elves came up with the idea to create a dark elf-free piece of land for those weary of the difficulties on the continent.[177] They used elven high magic, and while they succeeded at creating their island, Evermeet,[178] they damaged the continent, with accompanying casualties, among them many citizens of Ilythiir, as collateral damage.[169] Among this collateral damage was a large part of the church of Vhaeraun.[174] The Masked Lord's influence ebbed with the loss of his worshipers. According to Szorak Auzkovyn, Vhaeraun's salvage efforts were foiled by Eilistraee[30], through her favoring of female followers and excluding men from her clergy, thus causing a schism in the egalitarian church of Vhaeraun by seducing the women away to her.[179] Lolth then became the hegemonic deity in Ilythiir,[174] allowing her to start her machinations to corrupt and destroy all elves, which culminated in the Crown Wars.[118]

The Crown Wars[]

Aryvandaar, a sun elf kingdom, had borderline genocidal intentions regarding the dark elves of Ilythiir at latest after the Dark Disaster.[180] Geirildin Sethomiir, the coronal of Ilythiir, read even earlier those intentions in the actions of Aryvandaar. The coming battles were viewed and treated as battles for survival, so he made a pact with Lolth by proxy of Wendonai, around −11,500 DR,[181] to gain the power needed to save his people.[182] This act made Lolth the most important deity in Ilythiir.[181]

Nobles of Ilythiir followed the example of their coronal and made their own pacts,[183] and Vhaeraun, no longer the main deity, supported the dark elves of Ilythiir with servants and other support during the battles, alongside Ghaunadaur and Kiaransalee.[175]

It is not very clear what kind of role Vhaeraun filled during the Crown Wars, though it was known that it was not one as a warmonger; that role fell to Lolth and Ghaunadaur.[184]

The Ilythiiri, who were still refining their worship of the Dark Seldarine, used to portray their gods as spider deities, and high priests were killed by the offended gods for promoting this kind of iconography. Vhaeraun, for example, was depicted as a Masked Spider.[185]

The Crown Wars destroyed most elven realms, including Ilythiir.[103] By the end of this era, Vhaeraun and Lolth were enemies. (See Relationships.)

Vhaeraun and Eilistraee joined Lolth in forming the new drow pantheon. Other deities joined them later.[186]

Age of Humanity[]

- See also: Age of Humanity

At some point, some centuries before the third century DR, Zandilar, a deity worshiped by the elves in the Yuirwood at that time, tried to seduce Vhaeraun.[187] The background for this seduction attempt was that Lolth's followers had attacked the elves in the Yuirwood. The elves there trouble repelling any invaders, and thus Zandilar made habitual use of her seductiveness to get information and allies or to sway would be invaders away. Her target for seduction at that time was Vhaeraun. She tried to seduce the Masked Lord for information and/or assistance, but he imprisoned her intead, with the goal of stealing her power. Bast managed to create the opening for Zandilar to flee, and Zandilar let her savior take the remnants of her power, so that Bast could protect the elves in her place.[188] Vhaeraun's son Selvetarm was born just before the process of this merging, and he rejected his father out of personal uncertainty.[55]

War of the Spider Queen[]

- See also: War of the Spider Queen

- Silence of Lolth

In the Year of Wild Magic, 1372 DR, the goddess Lolth went into a state of hibernation, a period called the Silence of Lolth, with Selvetarm protecting her, as part of a plan to increase her power and separate her divine realm, the Demonweb Pits, from the Abyss.[189] Vhaeraun gained influence through unfurling his plans during this opportunity. His followers took over power by both legal[190] and violent means,[121] and Vhaeraun himself gained power from being sought out as an alternative patron, for example, by draegloths.[191]

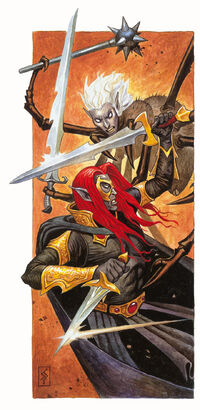

Vhaeraun and his son, Selvetarm, dueling.

In that same year, the drow of Menzoberranzan, through Triel Baenre, sent a group of powerful adventurers, led by Quenthel Baenre, to discover the cause of Lolth's silence (or, as was then suspected, disfavor). During Uktar, Quenthel's company finally managed to gain the collaboration of a cleric of Vhaeraun,[80] Tzirik Jaelre, who could lead them to the Demonweb Pits with the help of his god. However, they were betrayed by their Vhaeraunite guide, who summoned the Masked Lord as part of a plan to attack the defenseless Lolth.[192] After Vhaeraun grievously wounded her, Selvetarm appeared to battle Vhaeraun, but both fell off the web and plummeted into the darkness below. This battle caused significant damage to the fabric of the multiverse. Among other things, it caused a part of the Nine Hells to seep into Toril.[193] Tzirik tried to create another gate but, luckily for Lolth, failed because Pharaun Mizzrym managed to cast a sending spell across the planes—something that didn't always work[194]—and managed to order Jeggred Baenre to kill the Vhaeraunite priest.[195]

Another attempt at Lolth's life was made through a bargain Vhaeraun made with the yugoloth Inthracis. He couldn't act personally because of Lolth's ban against divine creatures entering her realm. The bargain consisted of the yugoloth and his army killing the potential candidates for the position of Lolth's Chosen, the vital component for her successful rebirth. In exchange, Vhaeraun was to assassinate Inthracis' superior, Kexxon, the Oinoloth, thus enabling the yugoloth's promotion, as payment on confirmation of success.[196] The attempt, however, failed.[197]

- After the Silence

After the Silence of Lolth, Eilistraee and Lolth started a divine game of sava over the destiny of the drow, Vhaeraun meddled with this game, though without wagering his life and those of his followers.[143][145] Nevertheless, he and his followers did plot another attempt against Lolth's life to end her reign. The idea was to open a gate between Ellaniath, Vhaeraun’s realm, and Eilistraee's portion of Arvandor, using elven high magic, so that the god could pass through and assassinate his sister. Then, the surface drow would be united under a single banner, increasing the number of Vhaeraun's followers and giving him the necessary power boost to kill his mother.[198]

However, such magic was very taxing and would have required the sacrifice of the souls of the casters. Because of this, the followers of the Masked Lord started to kill various priestesses of Eilistraee and collect their souls in their masks, using a spell called soultheft, to use the souls as a fuel for the ritual.[51]

On Nightal 20 of the Year of Risen Elfkin, 1375 DR, Vhaeraun managed to enter his sister Eilistraee's realm and attempted to assassinate her. The plan failed because of the machinations of Lolth, as conducted by Halisstra Melarn. She captured Malvag, the organizer of the undertaking and led Cavatina Xarann to him so he'd be killed and the soul in the mask freed by her. Halisstra then raised Malvag, so he could continue his undertaking. The church of Eilistraee had a program to revive every dead priestess because they were otherwise too small in number. Thus, the priestess whose soul was captured was revived; she conveyed her information, and The Dark Maiden was warned by Qilue Veladorn. With the warning, his secure success chance as an assassin was forfeit, and he lost the fight.[199] No mortal actually witnessed the battle that ensued, so what happened remains largely unknown. However, Eilistraee emerged from the battle alive, suggesting that Vhaeraun had failed and perished at the hand of his sister.[200] Eilistraee was changed after the event; she now held both her brother's and her own portfolios, and gained the title of "Masked Lady".[200][note 2]

The influence that Vhaeraun's portfolios had on Eilistraee manifested through outward changes, like her starting to wear clothes that hid her features, but also through a change in morale in her church. Her Chosen began spreading lies for propaganda's sake; engaging in bribery or ordering assassinations to ensure the silence of those who knew the truth became acceptable to her.[201][202] Eilistraee didn't have control over Vhaeraun's followers, and didn't seem to be fully capable of using his powers. To begin with, Vhaeraun's petitioners were capable of rejecting her.[203] His former clerics, even those who had actively worked against Eilistraee, were still able to receive spells, though not their strongest ones.[204] She also seemed unable to detect the betrayal of former clerics of Vhaeraun, whom she accepted as hers, when they joined forces with Ghaunadaur's to bring the doom of the Promenade of the Dark Maiden.[205]

Some of Vhaeraun's followers joined Eilistraee;[204] others refused to have anything to do with Eilistraee[206] and joined gods like Shar;[141] still others stayed with their old faith and/or never became aware that their god died, later forming the Skulkers of Vhaeraun.[207]

Post-Spellplague[]

- See also: Spellplague

Vhaeraun's death was a huge setback for the church, but it didn't kill his faith completely. Some drow who didn't believe his demise still worshiped him, and their prayers were actually answered. In fact, during that time, his followers (including lay worshipers) gained some divine abilities, (like that of producing poison, of disguising their appearance, or of small range teleportation,) which allowed them to complete dangerous tasks to further their cause and safely escape afterwards. They were called Skulkers of Vhaeraun and mostly consisted of disgruntled drow males but also included a few females. Speculations were that the entity answering their prayers could be identified as the remnants of Vhaeraun himself or possibly another god masquerading as the Masked Lord. Some believed that the fervor and faith of the followers were the source of their new powers.[207]

The Second Sundering[]

Vhaeraun managed to return to life and made the drow Phalar his Chosen[14] at some point before 1486 DR.[15] Vhaeraun made his return known to his followers, who then spread the information.[208] His church fully recovered as one when the Second Sundering was over.[17] Lolth gave him a divine realm in the Demonweb Pits.[3] Furthermore, praying to Vhaeraun in order to improve one's lot in life became an acceptable practice in main stream Lolthite drow society.[209] Something that was formerly a clear violation of the Way of Lolth.[210]

Vhaeraun and Eilistraee were separate entities again, both holding their portfolios and titles of old,[17][211] as well as their enmity.[3][note 3]

The wizard Mordenkainen claimed that, after the Second Sundering, Vhaeraun had dramatically steered away from his previous stance of rebellion against Lolth's system, and instead assumed a position of subservience to the Spider Queen, even coming to embody the ideal of drow male according to the Lolthite matriarchy: "swift, silent, obedient". According to Mordenkainen, Vhaeraun's faith even became tolerable in Lolth-controlled cities.[86]

Appendix[]

Notes[]

- ↑ While Eilistraee took part in those events, she didn't do so for personal gain but with the purpose of freeing the drow from Lolth's poison once and for all, endangering herself for that goal (Sacrifice of the Widow, p. 3). The Dark Maiden didn't see her followers as possessions; she strove to never forcefully intervene in their lives and to instead help them find their own path (Demihuman Deities, p. 12).

- ↑ The Grand History of the Realms explicitly says that Vhaeraun's assassination attempt failed and Eilistraee killed him. However, Ed Greenwood suggests that Eilistraee didn't actually kill her brother. The Dark Maiden defeated Vhaeraun with the indirect help of her ally Mystra, as the Weave frustrated the Masked Lord's magic while enhancing Eilistraee's. The goddess temporarily took her brother's portfolio, and trapped his sentience in the Weave, where it was enfolded in a dream by Mystra. The Lady of Mysteries did this to ensure that the two drow siblings would survive the cataclysm that she knew was coming—the Spellplague—in which she would be "killed" to renew the Weave and magic would go wild. After Mystra and the Weave were completely restored in 1487 DR, the goddess of magic could finally give Eilistraee her own lost power and do the same with Vhaeraun, after having awakened him from his dream.

- ↑ It was one of Ed Greenwood's ideas to have the two deities reach a reciprocal understanding, and to make the personal enmity between them was no more. More to read here: http://forum.candlekeep.com/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=19841&whichpage=21#476469

Appearances[]

- Novels

References[]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Eric L. Boyd (November 1999). Drizzt Do'Urden's Guide to the Underdark. Edited by Jeff Quick. (TSR, Inc.), p. 93. ISBN 0-7869-1509-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Robert Adducci (2016-03-01). Szith Morcane Unbound (DDEX03-15) (PDF). D&D Adventurers League: Rage of Demons (Wizards of the Coast), p. 9.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 36. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Thomas E. Rinschler (2001-06-06). Deities (PDF). Wizards of the Coast. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2017-07-23.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lisa Smedman (June 2008). Ascendancy of the Last. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 123. ISBN 978-0-7869-4864-2.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 40. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 12. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood, Sean K. Reynolds, Skip Williams, Rob Heinsoo (June 2001). Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3rd edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 237. ISBN 0-7869-1836-5.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 111, 113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Jason Carl, Sean K. Reynolds (October 2001). Lords of Darkness. Edited by Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 29. ISBN 07-8691-989-2.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Brian R. James, Eric Menge (August 2012). Menzoberranzan: City of Intrigue. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 21. ISBN 978-0786960361.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Erin M. Evans/MErinMEvans (2018-31-07). The Advesary, review spoilers.. Candlekeep Forum. Retrieved on 2018-31-07.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Erin M. Evans (December, 3. 2013). The Adversary (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 3960–4180. ASIN B00DACWB16.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 53. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Steve Kenson, et al. (November 2015). Sword Coast Adventurer's Guide. Edited by Kim Mohan. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 23, 108. ISBN 978-0-7869-6580-9.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (2014). Player's Handbook 5th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7869-6560-1.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins (November 2018). Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7869-6626-4.

- ↑ Doug Hyatt (July 2012). “Character Themes: Fringes of Drow Society”. In Steve Winter ed. Dragon #413 (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 4, 5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 118. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 170. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ Hal Maclean (September 2004). “Seven Deadly Domains”. In Matthew Sernett ed. Dragon #323 (Paizo Publishing, LLC), p. 65.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 36–40. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Colin McComb (October 1996). On Hallowed Ground. Edited by Ray Vallese. (TSR, Inc.), p. 100. ISBN 0-7869-0430-5.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 27.8 27.9 Ed Greenwood (July 1991). The Drow of the Underdark. (TSR, Inc), p. 42. ISBN 1-56076-132-6.

- ↑ Sean K. Reynolds (2002-05-04). Deity Do's and Don'ts (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Faiths and Pantheons. Wizards of the Coast. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2018-09-08.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Sean K. Reynolds (2004-08-18). Obsul Ssussun, "The Door to Light". Magic Books of Faerûn. Wizards of the Coast. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved on 2016-05-19.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 30.12 30.13 30.14 30.15 30.16 30.17 30.18 30.19 30.20 30.21 30.22 30.23 30.24 30.25 30.26 30.27 30.28 30.29 30.30 30.31 30.32 30.33 30.34 30.35 30.36 30.37 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 37. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 40. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 32.00 32.01 32.02 32.03 32.04 32.05 32.06 32.07 32.08 32.09 32.10 32.11 32.12 32.13 32.14 32.15 32.16 32.17 32.18 Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 114. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Steve Kenson, et al. (November 2015). Sword Coast Adventurer's Guide. Edited by Kim Mohan. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7869-6580-9.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 72. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 190. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 328. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), p. 63. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (2005). Resurrection Kindle Edition. (Wizards of the Coast). ISBN 978-0-7869-5686-9.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Paul S. Kemp (2005). Resurrection Kindle Edition. (Wizards of the Coast). ISBN 978-0-7869-5686-9.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 356. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 8–11. ISBN 0-7869-3981-8.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 252, 276. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 56. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 327. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (2005). Resurrection Kindle Edition. (Wizards of the Coast). ISBN 978-0-7869-5686-9.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 55. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 Jason Carl, Sean K. Reynolds (October 2001). Lords of Darkness. Edited by Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 29. ISBN 07-8691-989-2.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 244–257. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 278. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 360. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 78. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ 52.00 52.01 52.02 52.03 52.04 52.05 52.06 52.07 52.08 52.09 52.10 52.11 52.12 52.13 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 38. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 276. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 356–357. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 34. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), pp. 7, 63. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ Ari Marmell, Anthony Pryor, Robert J. Schwalb, Greg A. Vaughan (May 2007). Drow of the Underdark. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 185. ISBN 978-0-7869-4151-3.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 4. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 7–8, 113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Steve Kenson, et al. (November 2015). Sword Coast Adventurer's Guide. Edited by Kim Mohan. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7869-6580-9.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Ramon Arjona (2002-01-01). Alak Abaeir, Drow Assassin. Realms Personalities. Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved on 2016-07-17.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 255. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 9, 113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 179–186. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 226–233. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Colin McComb (December 1995). “Liber Malevolentiae”. In Michele Carter ed. Planes of Conflict (TSR, Inc.), p. 11. ISBN 0-7869-0309-0.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 198–211. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 247–253. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 51. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (July 2003). Daughter of the Drow (Mass Market Paperback). (Wizards of the Coast), p. 233. ISBN 978-0786929290.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 362. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 356–364. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 7, 113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (2005). Resurrection Kindle Edition. (Wizards of the Coast). ISBN 978-0-7869-5686-9.

- ↑ Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), p. 63. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 363. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 11. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Ed Greenwood (July 1991). The Drow of the Underdark. (TSR, Inc), pp. 42, 44. ISBN 1-56076-132-6.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 186–193. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 170. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ Colin McComb (October 1996). On Hallowed Ground. Edited by Ray Vallese. (TSR, Inc.), p. 101. ISBN 0-7869-0430-5.

- ↑ Sean K. Reynolds (2002-05-04). Deity Do's and Don'ts (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Faiths and Pantheons. Wizards of the Coast. pp. 8–9, 15. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2018-09-08.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 74. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (2007-04-25). Dragons of Faerûn, Part 3: City of Wyrmshadows (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Dragons of Faerûn. Wizards of the Coast. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2009-10-07.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 55, 56. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 46. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood/The Hooded One (2015-11-14). Questions for Ed Greenwood (2015). Candlekeep Forum.

- ↑ Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 68. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 68. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 33. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 94, 97, 100, 104, 108, 111, 114, 117, 120, 132. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 68. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 69. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 101. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 109. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Sean K. Reynolds, Duane Maxwell, Angel McCoy (August 2001). Magic of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 8. ISBN 0-7869-1964-7.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 131. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 36, 38, 131. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Skip Williams (February 2005). Races of the Wild. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-7869-3438-7.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 23. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 51. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 150. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 71. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), pp. 13–14. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 41. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 29. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), pp. 52–53. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 53. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 54. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Ramon Arjona (2002-11-13). The Ched Nasad Portal. Perilous Gateways Dark Elf Portals. Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved on 2016-07-16.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 13. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 50. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 109. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 15. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (January 2005). “Dark Dancer, Bright Dance”. Silverfall (Wizards of the Coast), p. 66. ISBN 0-7869-3572-3.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 118.3 Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 28. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Ramon Arjona (2002-11-06). Dark Elf Portals. Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved on 2016-12-29.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Eric L. Boyd (2007-04-25). Dragons of Faerûn, Part 3: City of Wyrmshadows (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Dragons of Faerûn. Wizards of the Coast. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2009-10-07.

- ↑ Reynolds, Forbeck, Jacobs, Boyd (March 2003). Races of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 118, 120. ISBN 0-7869-2875-1.

- ↑ Richard Baker (June 2006). Final Gate. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-7869-4002-6.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (June 2008). Ascendancy of the Last. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 246–247. ISBN 978-0-7869-4864-2.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 20, 38. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 12, 23. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Jeff Crook, Wil Upchurch, Eric L. Boyd (May 2005). Champions of Ruin. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 11. ISBN 0-7869-3692-4.

- ↑ Ramon Arjona (2003-02-03). Spider, Spider, Burning Bright…. Wizard of the Coast. Retrieved on 2017-01-26.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 261–268. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 227–234. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 247. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 247, 281. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Jeff Quick (October 2003). Underdark. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 126. ISBN 0-7869-3053-5.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1999). Drizzt Do'Urden's Guide to the Underdark. Edited by Jeff Quick. (TSR, Inc.), p. 126. ISBN 0-7869-1509-9.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 169. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 45. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood, Sean K. Reynolds, Skip Williams, Rob Heinsoo (June 2001). Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3rd edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 57. ISBN 0-7869-1836-5.

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 Lisa Smedman (June 2008). Ascendancy of the Last. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7869-4864-2.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1999). Drizzt Do'Urden's Guide to the Underdark. Edited by Jeff Quick. (TSR, Inc.), p. 90. ISBN 0-7869-1509-9.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Jeff Quick (October 2003). Underdark. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 175. ISBN 0-7869-3053-5.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 172. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 143.2 Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 3–5. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 23, 41, 112–113. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 191–192. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 174. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (July 2003). Daughter of the Drow (Mass Market Paperback). (Wizards of the Coast), p. 241. ISBN 978-0786929290.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Ed Greenwood, Chris Sims (August 2008). Forgotten Realms Campaign Guide. Edited by Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7869-4924-3.

- ↑ Reynolds, Forbeck, Jacobs, Boyd (March 2003). Races of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 37. ISBN 0-7869-2875-1.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Ed Greenwood, Chris Sims (August 2008). Forgotten Realms Campaign Guide. Edited by Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 258. ISBN 978-0-7869-4924-3.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 150. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ Sean K. Reynolds (2002-05-04). Deity Do's and Don'ts (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Faiths and Pantheons. Wizards of the Coast. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2018-09-08.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood, Eric L. Boyd (March 2006). Power of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 54. ISBN 0-7869-3910-9.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (July 1991). The Drow of the Underdark. (TSR, Inc), pp. 43–44. ISBN 1-56076-132-6.

- ↑ Sean K. Reynolds (2002-05-04). Deity Do's and Don'ts (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Faiths and Pantheons. Wizards of the Coast. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2018-09-08.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 51. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 61. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 56. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 46–51. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 61–66. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 59. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 168.0 168.1 Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ 169.0 169.1 169.2 169.3 169.4 Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 118. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 13–16. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 154. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 173. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 174.2 174.3 Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 174. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ 175.0 175.1 Reynolds, Forbeck, Jacobs, Boyd (March 2003). Races of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 35. ISBN 0-7869-2875-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 157. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 158. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (1999). Evermeet: Island of Elves. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 161. ISBN 0-7869-1354-1.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ 181.0 181.1 Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 52. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (June 2008). Ascendancy of the Last. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-7869-4864-2.

- ↑ Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 54. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (July 1991). The Drow of the Underdark. (TSR, Inc), p. 46. ISBN 1-56076-132-6.

- ↑ Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 59. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Jason Bulmahn, James Jacobs, Mike McArtor, Erik Mona, E.Wesley Schneider, Amber Stewart, Jeremy Walker (September 2007). “1d20 Villains: D&D's Most Wanted; Preferably Dead”. In Erik Mona ed. Dragon #359 (Paizo Publishing, LLC), p. 66.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1998). Demihuman Deities. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-7869-1239-1.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (September 1997). Powers & Pantheons. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 52. ISBN 978-0786906574.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 169–170. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ James Wyatt (2002-09-07). Underdark Campaigns (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for City of the Spider Queen. Wizards of the Coast. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved on 2009-10-07.

- ↑ Jeff Crook, Wil Upchurch, Eric L. Boyd (May 2005). Champions of Ruin. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 9, 11. ISBN 0-7869-3692-4.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 354–357. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Wyatt (March 2004). Player's Guide to Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 171. ISBN 0-7869-3134-5.

- ↑ Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams (July 2003). Player's Handbook v.3.5. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 275–276. ISBN 0-7869-2886-7.

- ↑ Richard Baker (May 2003). Condemnation. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 334–335, 341–342. ISBN 0786932023.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 217–241. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Paul S. Kemp (February 2006). Resurrection (Kindle ed.). (Wizards of the Coast), locs. 5374–5377. ASIN B0036S49H8.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (January 2007). Sacrifice of the Widow. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 78, 113–120, 123–127, 175, 300. ISBN 0-7869-4250-9.

- ↑ 200.0 200.1 Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ 204.0 204.1 Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (June 2008). Ascendancy of the Last. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 248–250. ISBN 978-0-7869-4864-2.

- ↑ Lisa Smedman (September 2007). Storm of the Dead. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7869-4701-0.

- ↑ 207.0 207.1 Doug Hyatt (July 2012). “Character Themes: Fringes of Drow Society”. In Steve Winter ed. Dragon #413 (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 59–64.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood/The Hooded One (2015-04-17). Questions for Ed Greenwood (2015). Candlekeep Forum.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (1992). Menzoberranzan (The City). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 13. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood/The Hooded One (2015-04-16). Questions for Ed Greenwood (2015). Candlekeep Forum.

Connections[]

Deities of unknown worship status in the Realms

Keptolo