Siege of Belgrade (1688)

| Siege of Belgrade (1688) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Turkish War, the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, and the Polish–Ottoman War | |||||||||

A folding screen depicting the siege of Belgrade commissioned by José Sarmiento de Valladares, most likely displayed in Mexico's viceregal palace. (c. 1697–1701) Brooklyn Museum | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Yeğen Osman Pasha | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 25,000–30,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,000 dead | 5,000 dead | ||||||||

The siege of Belgrade was a successful attempt by Habsburg troops under the command of the Elector of Bavaria Maximilian II Emanuel to capture the city of Belgrade from the Ottoman Empire. Part of the Great Turkish War (1683–1699), the siege lasted a month and culminated in the capture of the city on 6 September 1688. By conquering Belgrade, Habsburg forces gained an important strategic outpost, as the city had been the Ottoman's chief fortress in Europe for more than a century and a half. The Ottomans recaptured the city two years later, in October 1690. In 1693, Habsburg forces attempted to capture the city again, but failed.

Background

[edit]The Ottoman Empire suffered several major defeats at war with the Holy League, which significantly contributed to development of the crisis that resulted with the deposition of sultan Mehmed IV to advance into Ottoman territory. The Holy League decided to use this crisis to attack the Ottoman Empire. One of the main goals was the capture of Belgrade, one of the strongest Ottoman strongholds in Europe at that time, and also an important administrative, economic and cultural center.[1][2]

Prelude

[edit]The forces of Holy League advanced toward Belgrade from two directions. The forces that advanced along river Sava were under the command of the emperor Leopold I while forces that advanced along river Danube were under the command of the elector of Bavaria, Maximilian II Emanuel. According to the initial Ottoman plan, Yeğen Osman's forces moved from Belgrade to Šabac and further to Gradiška with the task not to allow the Leopold's army to cross to the right bank of Sava,[3][4] while Hasan Pasha, Ottoman serasker of Hungary, stayed in Belgrade waiting for money and military reinforcements from Asia before advancing toward the enemy. After receiving the news that Leopold's army had already crossed Sava and captured Kostajnica, Gradiška and the region around the river Una, Yeğen Osman returned to Belgrade.[5]

Forces and commanders

[edit]The forces of the Holy League were led by Maximilian II Emanuel with Prince Eugene of Savoy as one of his commanders.[6] In this battle they had 98 companies of infantry, 77 and a half escadrons of cavalry, and artillery forces of 98 cannons.[7] The Austrians were also accompanied by Serbian volunteers and members of Serbian Militia under the command of Jovan Monasterlija.[8][9]

by Joseph Vivien.

The Ottoman forces were commanded by Yeğen Osman who was shortly before this battle appointed to the position of governor of Belgrade.[10] In early 1688 Yeğen Osman went to Belgrade with his forces and forcefully deposed serdar Hasan Pasha and captured his camp on the Vračar hill.[11] Total number of forces under his command in Belgrade was 25–30,000.[6]

Battle

[edit]Maximilian began the movement of his forces on 30 July 1688 when they captured the Ottoman outpost near Titel. Yeğen Osman positioned his troops around Belgrade to prevent the fleeing of its garrison and population.[12]

Supported by the Christian population of Ottoman Serbia, his forces landed on Ada Ciganlija, a river island near Belgrade's suburb Ostružnica. On 7 August they positioned pontoon bridges between Ada Ciganlija and the right bank of the river Sava. The first group of 500 Austrian soldiers crossed the bridge under fire from Yeğen Osman's artillery.[7] When they established a foothold on the right bank of Sava, 10,000 supporting forces joined them. Yeğen Osman attacked them with the bulk of his forces, but the Austrians repelled his two attacks, captured more ground on the right bank of Sava, and brought additional forces.[13] They besieged the city and subjected it to cannon fire for nearly a month.

A day after the army of the Holy Roman Empire crossed the Sava, a letter written by the emperor Leopold I was brought to Yeğen Osman offering him Wallachia to desert the Ottomans and switch to their side.[11] On 10 August, Yeğen Osman gave a letter with his answer to the Austrian envoy and dispatched him from his camp. Since Yeğen Osman requested the whole of Slavonia and Bosnia, they did not make an agreement.[14] When Yeğen Osman realized that his forces were outnumbered, he burned his camp and both of the Serb populated Belgrade suburbs on the Sava and Danube. He then retreated to Smederevo and spent two days looting and burning it. Yeğen Osman left Smederevo and went to Niš via Smederevska Palanka.[15] From Niš, he wrote reports about the siege to the Ottoman government requesting urgent military and financial support needed to defend Belgrade. He recommended the annihilation of the rebellious rayah. Sublime Porte sent him 120 bags of gold and decided to mobilize the Muslim population of Rumelia to deal with the rebelling population of Belgrade pashalik.[16]

Upon refusal of his offer to accept the Ottoman garrison's surrender, Maximilian ordered an assault on 6 September. At first the Imperial forces wavered, but Maximilian, accompanied by Prince Eugene of Savoy, rallied the forces and drove the garrison from the walls. Maximilian's forces lost 4,000 men in the assault, while the Turks lost some 5,000. During the two-year period of Habsburg rule, the Belgrade fortress and town were rebuilt. In 1690 the Ottomans returned to besiege it and re-captured the city.[17]

Images

[edit]-

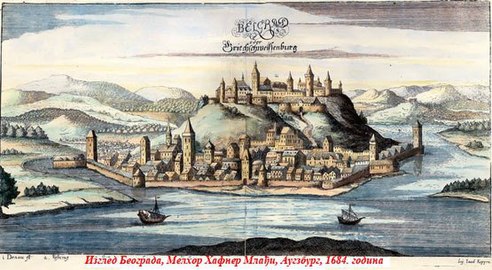

Belgrade in 1684

-

Map of the siege

-

Assault on Belgrade

References

[edit]- ^ Fotić 2005, p. 51-75.

- ^ Fotić 2018, p. 65-77.

- ^ Zbornik 1992, p. 87.

- ^ Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. Odeljenje istorijskih nauka 1974, p. 470.

- ^ Muzej 1982, p. 52.

- ^ a b Ilić-Agapova 2002, p. 126.

- ^ a b Recueil d'études orientales 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Davidov, Rapaić & Nikolić 1990, p. 121.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 143.

- ^ Wilson, Peter (1 November 2002). German Armies: War and German Society, 1648-1806. Routledge. p. 363. ISBN 978-1-135-37053-4.

To bring him to heel, the new sultan made Jegen governor of Belgrade early in 1688.

- ^ a b Recueil d'études orientales 1992, p. 108.

- ^ Zbornik 1992, p. 89.

- ^ Paunović 1968, p. 193.

- ^ Radonić 1955, p. 102.

- ^ Stanojević 1976, p. 103.

- ^ Milić 1983, p. 197.

- ^ Katić 2018, p. 79-99.

Sources

[edit]- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Davidov, D.; Rapaić, T.; Nikolić, D.M. (1990). Monuments of the Diocese of Buda. Library of Studies and Monographs (in Serbian). Education. ISBN 978-86-07-00480-5.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2005). "Belgrade: a Muslim and non-Muslim cultural centre (Sixteenth-Seventeenth centuries)". Provincial Elites in the Ottoman Empire: Helcyon Days in Crete V. Rethymno: Crete University Press. pp. 51–75.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2018). "The Belgrade Kadi's Müraseles of 1683: The Mirror of a Kadi's Administrative Duties". Belgrade: 1521-1867. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 65–77.

- Ilić-Agapova, Marija (2002). Ilustrovana istorija Beograda. Dereta. ISBN 9788673462431.

- Katić, Tatjana (2018). "Walking through the ravaged City: An Eyewitness Testimony to Demolition of the Belgrade Fortress in 1690". Belgrade: 1521-1867. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 79–99.

- Milić, Danica (1983). Istorija Niša: Od najstarijih vremena do oslobođenja od Turaka 1878. godine. Gradina.

- Paunović, Marinko (1968). Beograd: večiti grad. N.U. "Svetozar Marković,".

- Radonić, Jovan (1955). Durad II Branković.

- Stanojević, Gligor (1976). Srbija u vreme bečkog rata: 1683-1699 (in Serbian). Nolit.

- Annuaire de la ville de Beograd. Izd. Muzej grada Beograda. 1968.

- Muzej (1982). Zbornik Istorijskog muzeja Srbije. Muzej.

- Recueil d'études orientales. Akademija. 1992.

- Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. Odeljenje istorijskih nauka (1974). Istorija Beograda: Stari, srednji i novi vek. Prosveta.

- Zbornik (1992). Zbornik Matice srpske za istoriju. Матица.