Mabel Dwight

Mabel Dwight (1875–1955) was an American artist whose lithographs showed scenes of ordinary life with humor and tolerance. Carl Zigrosser, who had studied it carefully, wrote that "Her work is imbued with pity and compassion, a sense of irony, and the understanding that comes of deep experience."[1] Between the late 1920s and the early 1940s, she achieved both popularity and critical success. In 1936, Prints magazine named her one of the best living printmakers, and a critic at the time said she was one of the foremost lithographers in the United States.[2][3]

Early life and education

[edit]

Born in Cincinnati and raised in New Orleans, she moved with her parents to San Francisco in the late 1880s.[2] There, she studied with Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute.[4][5] Early in 1899, a critic for a local weekly magazine called The Wave said her portraits were the best ones in the show, "being handled with a degree of delicacy and feeling characteristic of the true colorist."[6] Later that year, she joined and became a director of the San Francisco Sketch Club.[7] In 1898, she drew the illustration for the cover of the club's exhibition catalog, shown here, Image No. 1. Two years later, she received a commission for a portrait from a monthly review called The Critic.[8] At about the same time, still living with her parents, she moved to Manhattan, and there a publisher commissioned her to make illustrations for a book about animals in the western United States. Her thirteen drawings included a frontispiece of deer, shown here, Image No. 2. A critic called the pictures "delightful", adding that they would appeal to readers old and young.[9]

In her mid-20s she accompanied Helen Bartlett Bridgman, wife of the explorer Herbert Lawrence Bridgman, on a world tour including stops in Egypt, Ceylon, India, Java, and Great Britain.[10] Returning to the United States in 1903, she rejoined her parents in Greenwich Village.[4][5] For the next few years she continued her efforts to establish herself as a professional artist and, from 1903 to 1906, listed herself in the American Art Annual as a painter and illustrator.[11] She met and in 1906 married fellow artist Eugene Patrick Higgins. Although they were both socialists, and hence espoused equality of the sexes, Dwight fell into the role of helpmate and stopped painting.[2][note 1]

Dwight and Higgins had no children. In 1917, they separated and she resumed her painting career.[5] The following year, she joined Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's newly founded Whitney Studio Club and became secretary to Juliana Force, the club's director.[2][note 2] Over the next few years she attended life drawing sessions and showed at annual exhibitions that the club held.[4] Although she made some experiments with etching, she worked mainly in watercolor at this time.[2] When she showed a painting called Nocturne at a club exhibition in December 1918, a critic for American Art News called it a "black picture" that had "a nude female figure of uncommon line and tone."[12] In 1923, she made a watercolor of a subject that would later reappear as one of her best-known lithographs. Showing people at a public aquarium, it was, a critic said, "both amusing and competently handled." The critic praised another of her paintings, called Portrait of a Man, for its "fine characterization" and rich color that "functions definitely in the achievement of form."[13] Reviewing another Whitney Club show, in 1926, a critic for the New York Sun said "Miss Dwight is a wit and in her paintings of subjects seized in the subway, the parks, and other public places weaves in a lot of insidious criticism of her fellow citizens."[14]

Mature style

[edit]-

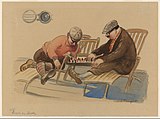

Image No. 3, Mabel Dwight, Chess on Deck, 1926 or 1927, watercolor and graphite, 8 7/8 x 12 1/8 inches

-

Image No. 4, Mabel Dwight, Basque Church, 1927, lithograph, 13 1/8 x 16 inches, edition of 12

-

Image No. 5, Mabel Dwight, Deserted Mansion, 1928, lithograph, 15 7/8 x 11 1/2 inches, edition of 50

-

Image No. 6, Mabel Dwight, Ferry Boat, 1930, lithograph, 11 1/2 x 16 inches

-

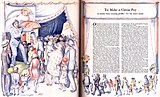

Image No. 7, Mabel Dwight, illustration from "How to Make a Circus Pay", 10 1/2 x 14 inches

-

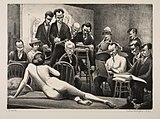

Image No. 8, Mabel Dwight, Life Class, 1931, lithograph, 13 1/8 × 16 15/16 inches

-

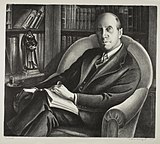

Image No. 9, Mabel Dwight, Portrait, 1935, lithograph, 13 5/8 x 15 1/4 inches

-

Image No. 10, Mabel Dwight, Queer Fish, 1936, lithograph, 10 5/8 x 13 inches

Dwight reached the age of 50 in 1925. She met the New York art print dealer Carl Zigrosser sometime before the outbreak of World War I, and, with his encouragement, traveled to Paris in 1926 to spend a year studying lithographic art in the Atelier Duchatel.[15][note 3] While in Paris, she made sketches showing people engaged in everyday activities—watching puppet shows, sitting in cafés, worshiping, browsing stalls by the Seine—and worked up the sketches into lithographic prints. In their posture and gestures as much as their facial expressions, the characters she depicted showed their personalities and individual foibles.[16] A watercolor she called Chess on Deck, shown here, Image No. 3, was probably made either on her outbound or inbound voyage. She made the lithograph called Basque Church, shown here, Image No. 4, while she was abroad. When the Philadelphia Print Club showed Dwight's complete lithographic works in 1929, C.H. Bonte, a critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, drew attention to prints of French scenes such as this, saying "She is above all interested in people and their characters. Rich is the skill which has been employed in giving individual distinction to all the details of this human comedy, for it is surely comedy as Miss Dwight sees it."[16]

Within a year of her return, the Paris prints and the ones she began to make in New York helped to establish her as one of America's best lithographic artists.[4] In 1928, Zigrosser arranged for her to be given a first solo exhibit.[2] That year, a critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that she had a "flair for the fantastic and romantic and can stir the imagination". The critic added, "Mabel Dwight, whose exhibition is being held at the Weyhe Galleries, has already won considerable reputation for herself in this medium" adding that she was "apt to respond to the humorous aspect of life."[17] In 1929 the Print Club of Philadelphia gave her a solo exhibition including all the prints she had made in Paris, Chartres, and New York through the end of the previous year. In a lengthy review, Margaret Breuning of the New York Evening Post wrote that the show contained "gay happy lithographs accomplished by a true artist, whose affectionate pulse is nicely attuned to the heartbeats of those she so faithfully depicts."[16]

A lithograph made in 1928 called Deserted Mansion was one of her first prints to attract substantial notice. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle critic called attention to it and her other "emotional pictures of deserted old houses".[17] A critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that she had infused the subject with a "sensed spirit of mystery" and thereby accomplished an "emotional trick of picture making".[18] Dwight later said the place reminded her of Jane Eyre, adding, "The upper windows were not boarded or shuttered, and they looked at one with that insane expression which windows of long empty houses acquire."[19] This print is shown here, Image No. 5.

A lithograph Dwight made in 1929 called Ferry Boat was chosen by the Institute of Graphic Arts as one of its "Fifty Prints of the Year".[20] In 1931, a critic said it was "highly amusing in its satire."[21] Writing in the New York Times, Edward Alden Jewell considered it one of her notable works in 1932 and in 1937 said it was then considered to be "long familiar".[22][23] A few years later, in a review of four contemporary printmakers, Zigrosser called this lithograph "immortal".[15] In 1930, Fortune magazine commissioned her to illustrate an article called "To Make a Circus Pay".[24] The illustration she made for the first two pages of the piece are shown here, Image No. 7. When, in 1932, she was given a second solo exhibition at the Weyhe Gallery, she showed watercolors and drawings as well as her prints.[22] The show drew from Edward Alden Jewell an evaluation of her capacity to evoke a range of moods in her work. He wrote that she depicted mansions that had become "solemn ghosts" along with graveyards and other somber subjects, but also presented "frankly carefree", even "hilarious" works showing circuses and rent parties.[22] Between the extremes, he cited pictures, such as Ferry Boat, that had become "more comfortable" to viewers.[22]

A 1931 lithograph called Life Class, shown here, Image No. 8, drew scant attention at the time but has more recently been analyzed in some detail. In 1952, a critic noticed in it Dwight's ability to personify specific events, employing a "sure and unflattering" touch.[25] In 1990, Christine Temin, writing in the Boston Globe explained that the picture commemorated the time when women were first allowed to join men in drawing nude models at the Whitney Studio Club. She wrote, "The sheer harmlessness of the scene makes a mockery of the sexist art world."[26] In 2014, an exhibition catalog pointed out that the model looks back at the artists just as they examine her and said the women sketchers in the picture could be seen "as representing the feminist idea of the male gaze."[27] In 1942, Zigrosser compared the picture to a very similar one by Peggy Bacon saying Bacon's was caricature while Dwight's was "drama" and added that Dwight's was "an assemblage of individual studies of characters, which by the logic of situation also acquire a comic aspect."[15]

By 1933, Dwight's reputation was firmly established. Her work had appeared in group exhibitions of the Whitney Studio Club, the Philadelphia Print Club, the Philadelphia Art Alliance and in solo exhibitions at the Weyhe Gallery and Duke University.[note 4] Her work had been featured in Vanity Fair seven times between November 1928 and September 1930.[30] By 1933, her paintings, drawings, and prints were present in collections of prominent museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[29][31] Writing in Publishers Weekly, Walter Pach had noted simply that she had been "acclaimed in the past few years".[32] Edward Alden Jewell had called her a "gifted American satirist".[22]

In 1935, she made a portrait that received little or no public notice at the time. Shown here, Image No. 9, it and her self-portrait, shown at top in the info box, illustrate her skill at portraiture. Critics observed this skill first in 1899 and again in 1923, as noted above. In 1997, a critic for the New York Times pointed to a "classical mode" in her portrait style.[33]

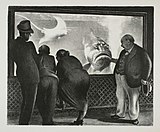

In 1936, she was listed as one of America's best printmakers in Prints magazine and, in a news article, was said to have "climbed to the top of a difficult and highly competitive field."[2][3] That year, she made a lithograph called Queer Fish that received popular and critical acclaim and would eventually become her most popular print.[4][34] Shown here, Image No. 10, it came from sketches she took at the New York Aquarium in Battery Park.[4] When it was shown two years later, a critic said it was "already famous for its humor."[35] Dwight herself later discussed it in some detail, saying:

It is dark under the balcony and the people are silhouetted black against the lighted tanks. ... People twist themselves into grotesque shapes as they lean on the rather low railing; posteriors loom large and long legs get tangled. One day I saw a huge Grouper fish and a fat man trying to out-stare each other; it was a psychological moment. The fish's mouth was open and his telescopic eyes focused intently. The man, startled by the sudden apparition, ... dropped his jaw; ... they hypnotized each other for a moment, then both swam away. Queer Fish!![4]

In 1934, Dwight joined the Public Works of Art Project. One of her biographers, Carol Kort, reports that despite her professional success, she was at that time in dire financial straits.[36] When that project disbanded, she joined the Federal Art Project of the Works Projects Administration and remained a federal employee until 1939.[37] During these five years she continued to be productive turning out prints that, "in the tradition of Honoré Daumier", as one source says, "combined humor with political commentary."[34] In addition to her financial difficulties, her health declined during these years. She suffered from asthma and became increasingly hard of hearing to the point of deafness.[5][38]

In 1936, Dwight contributed an essay to a book that the Federal Art Project intended to publish in order to demonstrate the importance and quality of the program and its artists. The government declined to publish at that time, and in 1973 the New York Graphic Society finally brought it to press (Art for the Millions; Essays from the 1930s by Srtists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, compiled by Francis V. O'Connor, Greenwich, Connecticut). In her essay, Dwight says aesthetic demands conflict with the satiric wish to show "the inevitable defects inherent in life". She names Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier as two of the very few masters who were able to resolve this conflict. Of the social realist art of her time, she writes, "Some of the young, class-conscious artists are too arrogantly vehement in their portrayals of vulgarity, ugliness, injustice, etc., and one is conscious of their agonized effort to twist the whole into a pattern of art. The result leaves the spectator indifferent." She notes that other artists of her time show people who are down and out, urban mean streets, and tawdry amusements without being satirists. "They frankly enjoy painting Coney Island, gasoline stations, hot-dog stands, cheap main streets, frame houses with jig-saw bands-all the Topsy-like growth of our cities." The essay ends with a statement that might apply to her own work. The artist, she says, should keep a "cool head and a warm heart". He or she does not need to exaggerate peoples' foibles since it is impossible to "rival nature, who herself has created beings so out of all reasonable proportion" [but] "has only to look at these people with sympathy and translate them into art to be just as tragic or humorous as he may wish."[39]

A decade after her first, Weyhe Gallery gave Dwight a third solo exhibition, this one encompassing some 93 works that, as a New York Times critic commented, spanned "from Paris scenes of 1927 to the mordant New York comments of succeeding years, to the Ferry Boat of 1930 and the much-admired Queer Fish of 1936.[40] Citing her "rich, healthy human commentary", a reviewer wrote, "Wherever masses of people circulate, on the ferryboats and street corners, in the parks and movie houses, Miss Dwight has found seemingly inexhaustible material. Her work is a rich, healthy human commentary. It is full of friendly humor. But the artist does not hide her feelings behind satire. We know where her sympathies lie. It is with the heavily burdened banana men, not the swollen butter-and-egg men."[41]

Of a showing of her Federal Art Project prints in Miami, a critic wrote, echoing Dwight's discussion of satire in art, "When distortion and exaggeration occur in these lithographs they are subtle, mature, and suggestive because they spring from sympathy rather than from arrogance and disdain." The critic added, "As a lithographer, Mabel Dwight stands among the best in America, although she only began working in this medium in 1927 when she was past 50."[42]

Later life and work

[edit]

The last years of the 1930s proved to be the high point of Dwight's career. In the early 1940s, her work continued to appear in New York group shows, including the Weyhe Gallery (1941, 1942), a collaborative dealers' show at the American Fine Arts Building (1941), and the National Academy of Design (1942), but after 1942 there were practically none.[note 5] When a group of her lithographs appeared at the St. Louis Art Museum in 1947, a critic noted that they had been printed in the 1930s. Calling them ""saturated with mood" and "pleasing to the eye", the critic praised her ability to portray "comic aspects with gaiety rather than sarcasm" and said the human figures she showed were "solid and carefully built up psychologically as well as physically."[43]

During the 1940s, Dwight made a watercolor called Farm House in the Fall, shown here, Image No. 12. After turning to lithography in 1926, she had continued to make some watercolors and colored drawings. In 1933, a watercolor she called Listening In was included in the Whitney Museum's first biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors, and prints.[44] Unlike Chess on Deck (Image No. 3) and most of her other work, its setting is rural and it contains no human or animal figures. In that respect, it may fall into a category mentioned in her essay on satire, in that it appears to address compositional problems and technical difficulties but not what she called "discrepancies between the real and the ideal".[39] From her earliest efforts onward, most her pictures were full either of human figures or subjects that evoked human emotions and were as one observer said, "probes into the depths of the drama of everyday human life".[36] In them, as another said, Dwight's empathy for her subjects is apparent as well as her droll sense of humor.[45]: 135 In a brief biography of Dwight, a curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum characterized Dwight as "keen observer of the human comedy, which she depicted with humor and compassion in her work."[46]

Politics

[edit]When I was a very young woman at an art student in San Francisco, some fellow students introduced me to socialism. The encounter was similar to "getting religion." My fervor shocked and alarmed my parents to such an extent that I was forced to go "underground" with my social ideas. This of course made the heat whiter. Art, too, I thought, must be an heroic comrade. This period of my life at least gave a definite bent to my later thought, and the reading done then directed my natural impulses. I was born with a hatred for the duality of poverty and riches. An early faith in a world without underdogs is a healthy experience, even if later experiences point to a world gone to the dogs. But whatever ups and downs of political or social faith I may have passed through, I have been true to the fundamental conviction that poverty is the great evil, a form of black plague inexcusable in a scientific age. — Mabel Dwight, "Satire in Art"[39]

Dwight was a lifelong socialist whose views were primarily based, as she wrote in her 1936 essay, "Satire in Art", on hatred of the vast distance that separated the poor from the rich in the United States.[39] In 1918, she joined with 49 other like-minded people in a pressure group called "Fifty Friends" that advocated clemency for men who were imprisoned for declaring themselves to be conscientious objectors during World War I.[47] Living in Manhattan during the 1930s, she joined one of the Marxist John Reed Clubs and supported another Popular Front organization, the American Artists' Congress. Nonetheless, not wishing to become a propagandist and fearing she would lose sales that she needed to support her precarious existence, she rarely produced works of an overtly political character.[5]

Family and personal life

[edit]Dwight was born on January 31, 1875, and named Mabel Jacque Williamson.[36][note 6] She was the only child of Paul Huston Williamson (1837–sometime after 1910) and his wife Adelaide (or Ada) Jacque (born 1875).[note 7]

Paul Williamson owned a farm near Cincinnati in Colerain Township, Hamilton County, Ohio. While Dwight was still a child, the family moved to New Orleans and Dwight was put in a convent school in Carrollton, outside the city.[5][note 8] In 1893, the Williamsons moved to San Francisco where Dwight was privately tutored while attending high school.[5] In the mid-1890s, Dwight completed her secondary education and, as noted above, began studies under Arthur Mathews at the Mark Hopkins Institute.[4]

Before she separated from Higgins, Dwight's friend Carl Zigrosser introduced her to an architectural draftsman named Roderick Seidenberg. He was a conscientious objector and militant socialist fourteen years younger than her.[5] Their relationship grew close and for some years they lived together.[5] It ended in 1929 when he took a job in the Soviet Union and, on returning, fell in love with, and then married another woman.[36] Dwight and Seidenberg became reconciled when Dwight suffered periods of illness during the 1930s and 1940s and Seidenberg and his wife Catherine took Dwight into their home to care for her.[50]

Following her divorce from Higgins, she neither kept her married nor resumed her maiden name, but rather, for reasons she did not disclose, chose the surname Dwight.[4] Her reticence about her name was not unusual in her. Even though she wrote an (unpublished) autobiography, much about her life is unknown.[5] Her hearing loss is an example. Some biographic summaries do not mention a hearing disability. Some say she was deaf, but do not specify the degree of hearing loss.[46] One source says she was nearly deaf and another says she was profoundly so.[51][52]

In 1929 or 1930 she traveled to New Mexico and this appears to have been the first and only time she traveled outside the Mid-Atlantic states after her return from Paris.[53] At about this time she moved from Greenwich Village to Staten Island and some time later moved to Pipersville, Pennsylvania.[54] After Dwight turned 65 in 1940, her deafness, chronic asthma, and poverty worsened.[5] Although she continued to work, her output dwindled, and she was confined to nursing homes in the period before her death following a stroke in 1955.[4]

Further reading

[edit]______________. A Century of Self-Expression: Modern American Art in The Collection of John and Joanne Payson (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr College, 2014)

Dwight, Mabel, "Satire in Art," in Art for the Millions; Essays From the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, edited by Francis V. O'Connor (Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1975, pp. 151–154)

Henkes, Robert. American Women Painters of the 1930s and 1940s; The Lives and Work of Ten Artists (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1991)

Kort, Carol, and Liz Sonneborn. A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts (New York, Facts on File, 2002)

Robinson, Susan Barnes, and John Pirog. Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs (Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997)

Zigrosser, Carl. "Mabel Dwight: Master of Comédie Humaine" (Artnews, Vol. 6, No. 126, June 1949, pp. 42–45)

ibid. The Artist in America; Twenty-Four Close-Ups of Contemporary Printmakers (New York, A.A. Knopf, 1942)

Notes

[edit]- ^ She later wrote: "domesticity followed and for many years [my] career as an artist was in abeyance."[5]

- ^ The Whitney Studio Club was an organization for promoting modern American art that evolved into the present-day Whitney Museum of American Art.

- ^ The Atelier Duchatel was a studio run by the widow of French lithographic printer Édouard Duchatel.[4]

- ^ She made her first appearance at the Whitney Studio Gallery in 1918.[12] Her work first appeared at the Print Club and Art Alliance in 1928.[28][18] Her Weyhe solo exhibitions have already been noted. She was given a solo exhibition in the women's college at Duke in 1933.[29]

- ^ This list of shows comes from articles appearing in the New York Times, 1940 to 1946, passim. Dwight's prints continued to appear in traveling shows but were reported to appear in only one New York group show after 1942: at Grand Central Galleries in 1946.

- ^ Dwight's birth date is given on a passport application she prepared in 1904. The record for this application on familysearch.org includes an image of the original.[48]

- ^ This information comes from Dwight's biographers, already cited, as well as the 1880 U.S. Census record for the family. The record on familysearch.org includes an image of the original.[49]

- ^ This information comes from Dwight's biographers, already cited, as well as the 1880 U.S. Census record for the family. The record on familysearch.org includes an image of the original.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ "About Mabel Dwight, Whose Work Is Too Compassionate To Be Classified as Caricature". Publishers Weekly. 2 (6): 138. October 1937.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stacey Schmidt (1997). "Artist Biographies". Between the Wars: Women Artists of the Whitney Studio Club and Museum. Whitney Museum of American Art. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- ^ a b "Just Between Ourselves". Times Record. Troy, New York. 1936-12-21. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patricia Junker; Barbara McCandless (2001). Will Gillham (ed.). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. Hudson Hills. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-55595-198-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Mabel Dwight: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Lithographs by Susan Barnes Robinson and John Pirog Frankenthaler: A Catalogue Raisonné, Prints 1961-1994 by Pegram Harrison and Suzanne Boorsch". Woman's Art Journal. 20 (2): 52–55. Autumn 1999. JSTOR 1358988.

- ^ "Things and People". The Wave: 325. 1899-05-20.

- ^ "Art and the Artists". San Francisco Call. 1897-11-07. p. E7.

- ^ "The Drama". The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature, Art and Life. 39 (5): 434. November 1901.

- ^ "Books and Bookmen". Standard Union. Brooklyn, New York. 1903-11-29. p. 19.

- ^ "The Social World". Standard Union. Brooklyn, New York. 1904-12-12. p. 7.

- ^ American Art Annual, Volume 5, 1905-06. American Art Annual, New York. 1905. p. 491.

Williamson, Mabel. 60 Washington Square S., New York, N. Y. (P., I.)

- ^ a b "Whitney Club Exhibition". American Art News. 17 (11): 7. 1908-12-21.

- ^ "Whitney Studio Club". Evening Post. New York, New York. 1923-12-29. p. 14.

- ^ "Whitney Studio Club Shows Work of Five". New York Sun. New York, New York. 1926-04-17.

- ^ a b c The artist in America; Twenty-Four Close-Ups of Contemporary Printmakers. A.A. Knopf. 1942. pp. 145–150.

- ^ a b c C. H. Bonte (1939-01-20). "In Gallery and Studio; An Intensely Modernistic Exhibition and Two Others That Are Just Slightly Tinged; Nine-Woman Show at the Plastic Club and Mabel Dwight's Richly Humorous Lithographs". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b "Work of Three American Lithographers Exhibited". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1928-12-02. p. E7.

- ^ a b C.H. Bonte (1928-12-09). "In Gallery and Studio". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 7.

- ^ Burns, Sarah (Fall 2012). ""Better for Haunts": Victorian Houses and the Modern Imagination". American Art. 26 (3): 2–25. doi:10.1086/669220. JSTOR 10.1086/669220. S2CID 190697128.

- ^ "Among the Print Makers, Old and Modern; The "Fifty Prints"". Art Digest. 5 (10): 19. 1931-02-15.

- ^ "Art News". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. 1931-11-07. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Edward Alden Jewell (1932-01-09). "Mabel Dwight in Varied Moods". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 20.

- ^ "Etchers' Society to Open Exhibition: Lithographs, Block Prints and Woodcuts Will Be Shown at National Arts Club". New York Times. New York, New York. 1937-02-03. p. 21.

- ^ "To Make a Circus Pay". Fortune. 1 (3): 39–43. February 1930.

- ^ Mary L. Alexander (1952-12-21). "Mabel Dwight". Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati, Ohio. p. 12.

- ^ "Print Exhibit Kicks Off BPL Celebration". Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. 1990-12-19. p. 69.

- ^ Jon Sweitzer-Lamme (2014). A Century of Self-Expression; Modern American Art in the Collection of John and Joanne Payson [Exhibition Catalog]. Bryn Mawr College. p. 42. ISBN 9780615348261.

- ^ C.H. Bonte (1928-10-28). "In Gallery and Studio". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 20.

- ^ a b "Lithographs Will Be Shown at Duke". Herald-Sun. Durham, North Carolina. 1933-04-03. p. 2.

- ^ "Vanity Fair Archive: Mabel Dwight". vanityfair.com. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ "Mabel Dwight, 79, Artist, Is Dead". Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. 1955-09-06. p. 9.

- ^ "The Weyhe Book and Print Shop". Publishers Weekly. 115 (12): 1397. 1929-03-23.

- ^ William Zimmer (1997-09-28). "At the Whitney, Feisty Women From an Earlier Era". New York Times. New York, New York. p. 16.

- ^ a b Margaret Moore Booker (2011). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-19-533579-8.

- ^ Laura A. Coleman (1938-02-18). "Art News and Views". News Leader. Richmond, Virginia. p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Facts on File. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8160-4397-3.

- ^ The Federal Art Project : American prints from the 1930s in the Collection of the University of Michigan Museum of Art. University of Michigan. 1985. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780912303307.

- ^ "Hard of Hearing Lecture at Y.W.C.A". The News. Paterson, New Jersey. 1936-03-10. p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Francis V. O'Connor (1973). Art for the Millions; Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project. New York Graphic Society. pp. 151–154. ISBN 9780821204399.

- ^ "Among the Solo Shows". New York Times. New York, New York. 1938-01-09. p. X10.

- ^ ""The Eight" and Other U.S. Artists Exhibit". New York Post. New York, New York. 1938-01-22. p. 19.

- ^ John Parry (1941-10-12). "Art Center to Exhibit Lithographs". Miami News. Miami, Florida. p. 18.

- ^ "Cecile Parrish Swingle". Lincoln Star. Lincoln, Nebraska. 1947-09-25. p. 5.

- ^ Biennial exhibition of contemporary American sculpture, watercolors. Whitney Museum of American Art. 1933. p. 15.

- ^ Robert Henkes (1991). American Women Painters of the 1930s and 1940s: the Lives and Work of Ten Artists. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 109. ISBN 9780899504742.

- ^ a b "Mabel Dwight". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ^ ""Fifty Friends" Placed with Baker to Free Objectors". New York Tribune. New York, New York. 1918-12-25. p. 14.

- ^ "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925". Passport Application, New York, United States, source certificate #95798, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., Roll 665, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ a b "Paul H Williamson, Colerain, Hamilton, Ohio, United States". United States Census, 1880, sheet 68C, NARA microfilm publication T9 on FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ^ "Mabel Dwight Correspondence with Carl Zigrosser, 1915-1967, n.d." Franklin Library, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Holger Cahill, 1960 Apr. 12 and Apr. 15". Oral Histories; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ^ Christine Bold (1999). The WPA Guides: Mapping America. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-57806-195-2.

Mabel Dwight's lithograph "Derelicts (East River Water Front)" represents the same subject matter in more grotesque yet more intimate light: her men touch and lean on each other with a degree of dependency not indicated by the more public photograph. Dwight—an elderly, partly deaf employee of the New York City Art Project—generally makes graphic the quotidian camaraderie of the working classes and the destitute, humanizing some of the guidebook's stark information.

- ^ "Mabel Dwight". AskArt Artists' Bluebook. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ^ "Mabel Dwight, Artist, Dies". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1955-09-06. p. 32.

![]() Media related to Mabel Dwight at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mabel Dwight at Wikimedia Commons

- 1875 births

- 1955 deaths

- Artists from New York City

- Artists from San Francisco

- 20th-century American artists

- American modern artists

- 20th-century American women artists

- American women printmakers

- Federal Art Project artists

- 20th-century American printmakers

- American lithographers

- 20th-century lithographers

- Women lithographers

- American expatriates in France