Dundalk (/dʌnˈdɔː(l)k/ dun-DAW(L)K;[5] Irish: Dún Dealgan) is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is halfway between Dublin and Belfast, close to the border with Northern Ireland. It is surrounded by several townlands and villages that form the wider Dundalk Municipal District. It is the seventh largest urban area in Ireland, with a population of 43,112 as of the 2022 census.

Dundalk

Dún Dealgan | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Clockwise from top: Castle Roche, Clarke Station, St. Patrick's Church, The Marshes Shopping Centre, Market Square, Dundalk Institute of Technology | |

| Motto(s): Irish: Mé do rug Cú Chulainn cróga 'I gave birth to brave Cú Chulainn' | |

| Coordinates: 54°00′16″N 06°24′01″W / 54.00444°N 6.40028°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Louth |

| Inhabited | c. 3700 BC |

| Charter | 1189 AD |

| Government | |

| • Dáil constituency | Louth |

| • EU Parliament | Midlands–North-West |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 21.7 km2 (8.4 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 320.8 km2 (123.9 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Rank | 7th |

| • Urban | 43,112[3] |

| • Metro | 64,287[4] |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing key | A91 |

| Telephone area code | +353(0)42 |

| Irish Grid Reference | J048074 |

| Website | www |

Having been inhabited since the Neolithic period, Dundalk was established as a Norman stronghold in the 12th century following the Norman invasion of Ireland, and it became the northernmost outpost of The Pale in the Late Middle Ages. The town came to be nicknamed the "Gap of the North" where the northernmost point of the province of Leinster meets the province of Ulster. The modern street layout dates from the early 18th century and owes its form to James Hamilton (later 1st Earl of Clanbrassil). The legends of the mythical warrior hero Cú Chulainn are set in the district, and the motto on the town's coat of arms is Irish: Mé do rug Cú Chulainn cróga ("I gave birth to brave Cú Chulainn").

The town developed brewing, distilling, tobacco, textile, and engineering industries during the 19th century. It became prosperous and its population grew as it became an important manufacturing and trading centre—both as a hub on the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) network and with its maritime link to Liverpool from the Port of Dundalk. It later suffered from high unemployment and urban decay after these industries closed or scaled back both in the aftermath of the Partition of Ireland in 1921 and following the accession of Ireland to the European Economic Community in 1973. New industries have been established in the early part of the 21st century, including pharmaceutical, technology, financial services, and specialist foods.

There is one third-level education institute—Dundalk Institute of Technology. The largest theatre in the town, An Táin Arts Centre (named after the epic of Irish mythology), is housed in Dundalk Town Hall, and the restored buildings of the nearby former Dundalk Distillery house both the County Museum Dundalk and the Louth County Library. Sporting clubs include Dundalk Football Club (who play at Oriel Park), Dundalk Rugby Club, Dundalk Golf Club, and several clubs competing in Gaelic games. Dundalk Stadium is a horse and greyhound racing venue and is Ireland's only all-weather horse racing track.

History

editToponymy

editDundalk is an anglicisation of Irish: Dún Dealgan [ˌd̪ˠuːnˠ ˈdʲalˠəgənˠ] that was adopted by the first Norman settlers of the area in the 12th century. It means "the fort of Dealgan" (Dún being a type of medieval fort and Delga being the name of a mythical Fir Bolg Chieftain). The site of Dún Dealgan is traditionally associated with the ringfort known to have existed at Castletown Mount before the arrival of the Normans. The first mention of Dundalk in historical sources appears in the Annals of Ulster, which record that Brian Boru met the King of Ulster at "Dún Delgain" in 1002 to demand submission. 12th century versions of the Táin Bó Cúailnge feature "Delga in Muirtheimne".[6] The manor house built by Bertram de Verdon at Castletown Mount on the site of the earlier settlement is referred to as the "Castle of Dundalc" in the 12th century records of the Gormanston Register.[7]

Early history and legend

editArchaeological studies at Rockmarshall on the Cooley peninsula indicate that the Dundalk district was first inhabited circa 3700 BC during the Neolithic period.[8] Pre-Christian archaeological sites in the Dundalk Municipal District include the Proleek Dolmen (a portal tomb) in Ballymascanlon, which dates to around 3000 BC,[9] the nearby "Giant's Grave" (a wedge-shaped gallery grave), Rockmarshall Court Tomb (a court cairn),[10] and Aghnaskeagh Cairns (a chambered cairn and portal tomb).[11][12]

The legends of Cú Chulainn, including the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), an epic of early Irish literature, are set in the first century AD, before the arrival of Christianity to Ireland. Clochafarmore, the menhir that Cú Chulainn reputedly tied himself to before he died, is located to the west of the town, near Knockbridge.[13]

Saint Brigid is reputed to have been born in 451 AD in Faughart.[14] A shrine to her is located at Faughart.[15] St Brigid's Church in Kilcurry holds what worshippers believe is a relic of the saint—a fragment of her skull.[16]

Most of what is recorded about the Dundalk area between the 5th century and the foundation of the town as a Norman stronghold in the 12th century comes from the Annals of the Four Masters and the Annals of Tigernach, which were both written hundreds of years after the events they record. According to the annals, the area that is now Dundalk was known as Magh Muirthemne (the Plain of the Dark Sea). It was bordered to the northeast by Cuailgne (Cooley) and to the south by the Ciannachta. It was ruled by a Cruthin kingdom known as Conaille Muirtheimne (who were aligned to the Ulaid) in the early Christian period.[17]

There are several references in the annals to battles fought in the district such as the 'Battle of Fochart' in 732, which are folklore.[18] Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn recounts the mythical tale of a 10th-century naval battle in Dundalk Bay. Sitric, son of Turgesius and ruler of the Lochlannaigh in Ireland, had offered Cellachán Caisil, the King of Munster, his sister in marriage. But it was a trick to take the king prisoner and he was captured and held hostage in Armagh. An army was raised in Munster and marched on Armagh to free the king, but Sitric retreated to Dundalk and moved his hostages to his ship in Dundalk Bay as the Munster army approached. A fleet from Munster commanded by the King of Desmond, Failbhe Fion, attacked the Danes in the bay from the south. During the sea battle, Failbhe Fion boarded Sitric's ship and freed Cellachán, but was killed by Sitric who put Failbhe Fion's head on a pole. Failbhe Fion's second in command, Fingal, seized Sitric by the neck and jumped into the sea where they both drowned. Two more Irish captains each grabbed one of Sitric's two brothers and did the same, and the Danes were subsequently routed.[19]

There is a high concentration of souterrains in north Louth, particularly along the western periphery of the town including at Castletown Mount, which is evidence of settlements from early Christian Ireland.[20] This indicates that the area was regularly subject to raids and the discovery of a type of pottery known as 'souterrain ware', which has only been found in north Louth, County Down and County Antrim, suggests that these areas shared cultural ties separate from the rest of early historic Ireland. The number of souterrains drops significantly on crossing the River Fane to the south, indicating that the district was a border area between separate kingdoms.[6]

Archaeological and historical research suggests that before the arrival of the Normans, the district was composed of rural settlements of ringforts located on the higher ground that surrounds the present-day town.[6] There are references in the annals and folklore to a pre-Norman town located in the present-day Seatown area, east of the town centre. This area was alternatively called Traghbaile and later Sraidbhaile in Irish.[21] These names could have derived from the folkloric tale of the death of Bailé Mac Buain—hence Traghbaile, meaning 'Bailé's Strand', or Sraid Baile mac Buain, meaning the street town of Bailé Mac Buain. Dundalk continued to be referred to as 'Sraidbhaile' in Irish into the 20th Century.[22][23][24]

Norman arrival

editBy the time of the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, Magh Muirthemne had been absorbed into the kingdom of Airgíalla (Oriel) under the Ó Cearbhaills.[25] In about 1185, Bertram de Verdun, a counsel of Henry II of England, erected a manor house at Castletown Mount on the ancient site of Dún Dealgan.[6] De Verdon founded his settlement seemingly without resistance from Airgíalla (the Ó Cearbhaills are recorded as having submitted to Henry by this time),[26] and in 1187 he founded an Augustinian friary under the patronage of St Leonard.[27] He was awarded the lands around what is now Dundalk by Prince John on the death of Murchadh Ó Cearbhaill in 1189.[28]

On de Verdun's death in Jaffa in 1192 at the end of the Third Crusade, his lands at Dundalk passed to his son Thomas and then to his second son Nicholas after Thomas died. In 1236, Nicholas's daughter Roesia commissioned Castle Roche, 8 km north-west of the present-day town centre, on a large rocky outcrop with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. It was completed by her son, John, in the 1260s.[29]

Castle Roche was destroyed in 1315 by the armies of Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king Robert the Bruce, as they made their way south through Ulster during the Bruce campaign in Ireland. They then attacked the town and massacred its population. After taking possession of the town, Bruce proclaimed himself King of Ireland. Following three more years of battles across the north-eastern part of the island, Bruce was killed and his army defeated at the Battle of Faughart by a force led by John de Birmingham, who was created the 1st Earl of Louth as a reward.[30]

Later generations of de Verduns continued to own lands at Dundalk into the 14th century. Following the death of Theobald de Verdun, 2nd Baron Verdun in 1316 without a male heir, the family's landholdings were split. One of Theobold de Verdun's daughters, Joan, married the second Baron Furnivall, Thomas de Furnivall, and his family subsequently acquired much of the de Verdun land at Dundalk.[27] The de Furnivall family's coat of arms formed the basis of the seal of the 'New Town of Dundalk'—a 14th-century seal discovered in the early 20th century, which became the town's coat of arms in 1968.[31] The 'new town' that was established in the 13th century is the present-day town centre; the 'old town of the Castle of Dundalk' being the original de Verdun settlement at Castletown Mount 2 km to the west.[32] The de Furnivalls then sold their holdings to the Bellew family, another Norman family long established in County Meath.[32] The town was granted its first formal charter as a 'New Town' in the late 14th century under the reign of Richard II of England.[33]

Effectively a frontier town as the northernmost outpost of The Pale, Dundalk continued to grow as the 14th and 15th centuries progressed. The town was heavily fortified, as it was regularly attacked—with at least 14 separate assaults, sieges or demands for tribute by a resurgent native Irish population recorded between 1300 and 1600 (with more than that number being likely).[34]

English rule

editIn 1540, the Priory of St Leonard founded by Bertram de Verdun was surrendered to the Crown because of Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries.[35] During the subsequent Tudor conquest of Ireland, Dundalk remained the northern outpost of English rule. In 1600, the town was used as a base of operations for the English, led by Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, for their push into Ulster through the 'Gap of the North' (the Moyry Pass) during the Nine Years' War.[36]

Following the Flight of the Earls, the subsequent Plantation of Ulster (and the associated suppression of Catholicism) resulted in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. After only token resistance, Dundalk was occupied by an Ulster Irish Catholic army on 31 October. They subsequently tried and failed to take Drogheda and retreated to Dundalk. The Royal Irish Army, who were led by the Duke of Ormond (and known as Ormondists), in turn, laid siege to Dundalk and overran and plundered the town in March 1642, killing many inhabitants.[37]

The Ormondists held the town during the English Civil War until it was occupied by the Northern Parliamentary Army of George Monck. The Parliamentarians held it for two years before surrendering it back to the Ormondists. It was then retaken by the forces of Oliver Cromwell, who had landed in Ireland in August 1649 and sacked Drogheda. After the massacre in Drogheda, Cromwell wrote to the Ormondist commander in Dundalk warning him that his garrison would suffer the same fate if it did not surrender. The Duke of Ormond ordered the commander to have his men burn the town before his retreat, but they did not do so such was their haste to leave. For the remainder of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, the town was again used as a base for operations against the Irish in Ulster.[37]

After the Restoration of the monarchy, the Corporation of Dundalk was granted a new charter by Charles II on 4 March 1673. The forfeiture of property and settlements carried out during the Restoration saw much of the land of Dundalk granted to Marcus Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon, who had fought for both sides in the civil war. Even though the Bellews were seen as Papists, Sir John Bellew appears to have held onto much of his family's legacy landholdings.[37]

When the Williamite War in Ireland began in 1689, the Williamite commander Schomberg landed in Belfast and marched unopposed to Dundalk but, as the bulk of his forces were raw and undisciplined as well as inferior in numbers to the Jacobite Irish Army, he decided against risking a battle. He entrenched himself at Dundalk and declined to be drawn beyond the circle of his defences. With poor logistics and struck by disease, over 5,000 of his troops died.[38]

After the end of the Williamite War, the third Viscount Dungannon, Mark Trevor, sold the Dundalk estate to James Hamilton of Tollymore, County Down. Hamilton's son, also James, was created Viscount Limerick in 1719 and then the first Earl of Clanbrassil in 1756. The modern town of Dundalk owes its form to Hamilton. The military activity of the 17th century had left the town's walls in ruins. With the collapse of the Gaelic aristocracy and the total takeover of the country by the English, Dundalk was no longer a frontier town and no longer had a need for its 15th-century fortifications. Hamilton commissioned the construction of streets leading to the town centre; his ideas stemming from his visits to Continental Europe. In addition to the demolition of the old walls and castles, he had new roads laid out eastwards of the principal streets.[39]

When the first Earl died in 1758, the estates passed to his son, the second Earl of Clanbrassil, who died without an heir in 1798. The Earl of Roden inherited the Dundalk estate because the second Earl's sister, Lady Anne Hamilton, had married Robert Jocelyn, the first Earl of Roden. Portions of the Roden Dundalk estate were sold under the auspices of the various land acts of the 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the Irish Free State government lands purchase acts of the 1920s. The remaining freeholds and ground rents were sold in 2006, severing the links between the Earls of Roden and the town of Dundalk.[40]

During the 18th century, Ireland was controlled by the minority Anglican Protestant Ascendancy via the Penal Laws, which discriminated against both the majority Irish Catholic population and Dissenters. Mirroring other boroughs around the country, Dundalk Corporation was a 'closed shop', consisting of an electorate of 'freemen' (mostly absentee landlords of the Ascendancy). The Earl of Clanbrassil controlled the procedures for both the nomination of new freemen and the nomination of parliamentary candidates, therefore disenfranchising the local populace.[41] In the late 18th century, the United Irishmen movement, inspired by the American and French revolutions, led to the Rebellion of 1798.[42] In north Louth, the authorities had successfully suppressed the activities of the United Irishmen prior to the rebellion with the help of informants, and several local leaders had been rounded up and imprisoned in Dundalk Gaol. An attack on the military barracks and gaol to free prisoners was planned for 21 June 1798. The attack failed because of a thunderstorm, which dispersed the gathered United Irish volunteers, and two of the jailed leaders—Anthony Marmion and John Hoey—were subsequently tried for treason and hanged.[41]

After the Acts of Union

editFollowing the Act of Union, which came into force on 1 January 1801, The 19th century saw industrial expansion in the town (see Economy) and the construction of several buildings that are landmarks in the town.[43] The first railway links arrived when the Dundalk and Enniskillen Railway opened a line from Quay Street to Castleblayney in 1849, and by 1860 the company operated a route northwest to Derry. Also in 1849, the Dublin and Belfast Junction Railway opened Dundalk railway station. Following a series of mergers, both lines were incorporated into the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) in 1876.[44]

The established and merchant classes prospered alongside a general population that suffered from poverty. A typhus epidemic struck in the 1810s, potato-crop failures in the 1820s caused famine, and a cholera epidemic struck in the 1830s.[45] During the Great Famine of the 1840s, the town did not suffer to the same extent as the west and south of Ireland. Cereal-based agriculture, new industries, construction projects, and the arrival of the railway all contributed to sparing the town of its worst effects.[45] Nevertheless, so many people died in the Dundalk Union Workhouse that the graveyard was quickly filled. A second graveyard was opened on the Ardee Road—the Dundalk Famine Graveyard—which is known to contain approximately 4,000 bodies. It was closed in 1905 and was left derelict until the 21st century when local volunteers worked to restore it.[46]

The latter part of the 19th century was dominated by the Irish Home Rule movement and Dundalk became a focal point of the politics of the time. The Irish National Land League held a demonstration in Dundalk on New Year's Day, 1881, stated by the local press to be the largest gathering ever seen in the town.[47]

As the Home Rule movement developed, the sitting Home Rule League MP, Philip Callan, fell out with party leader Charles Stewart Parnell, who travelled to Dundalk to oversee efforts to have Callan unseated. Parnell's candidate, Joseph Nolan, defeated Callan in the election of 1885 after a campaign of voter suppression and intimidation on both sides.[48] Following the split in the Irish Parliamentary Party, the leading anti-Parnellite, Tim Healy, won the North Louth seat in 1892, defeating Nolan (who had stayed loyal to Parnell). The campaign, predicted by Healy to be "the nastiest fight in Ireland", saw running battles and mass brawls in the streets between Parnellites, 'Healyites', and 'Callanites'—supporters of Philip Callan, who was trying to regain his seat.[49]

The local Sinn Féin cumann was founded in 1907 by Patrick Hughes. It struggled to grow beyond a handful of members because of the dominance of the existing political factions.[50] In 1910, on the accession of George V to the English throne, the local High Sheriff, accompanied by police and soldiers, led a proclamation to the new king at the Market Square. The ceremony was interrupted by the local Sinn Féin members, who raised a tricolour beside the Maid of Erin monument and chanted "God Save Ireland" during a rendition of "God Save the King"—giving the party visibility in the town for the first time.[51]

Approximately 2,500 men from Louth volunteered for Allied regiments in World War I and it is estimated that 307 men from the Dundalk district died during the war.[52] In the months before the outbreak of the war, the G.N.R. converted nine of its carriages into a mobile 'ambulance train', which could hold 100 wounded soldiers. Ambulance Train 13 was kept in service for the duration of the war before being decommissioned in 1919.[53] The war came to Dundalk weeks before the Armistice, when the S.S. Dundalk was sunk by a German U-boat on 14 October 1918 on a voyage from Liverpool to Dundalk. 20 crew-members were killed, while 12 were rescued.[54]

Meanwhile, the Easter Rising had changed the political landscape. 80 members of the Irish Volunteers had left Dundalk to take part in the Rising. After the countermanding order of Eoin MacNeill, members of the unit ended up in Castlebellingham, trying to evade the Dundalk RIC. There, they held several RIC men and a British Army officer at gunpoint until one of the Volunteers, believing the army officer was reaching for a hidden weapon, fired at the captives, killing RIC constable Charles McGee. After the Rising ended, the Volunteers went on the run and most were captured. Four were sentenced to death for the murder of Constable McGee but were released in the general amnesty of 1917.[55]

Independence

editIn the 1918 Irish general election, Louth elected its first Sinn Féin MP when John J. O'Kelly defeated the sitting MP, Richard Hazleton of the Irish Parliamentary Party, in the closest contest of the election—O'Kelly winning by 255 votes. In the run-up to the election, the local newspapers had supported the Irish Party over Sinn Féin and complained afterwards that the area of Drogheda in County Meath that was included in the Louth constituency had tipped the contest in Sinn Féin's favour.[56] Again, the campaign saw reports of widespread violence and intimidation tactics.[57]

There was no strategic military action in north Louth during the Irish War of Independence. Activity consisted of acts of sabotage and attacks on the RIC to seize arms. Arson attacks were a feature of the period in particular.[58] Crown forces committed reprisal attacks in response, hardening support for Sinn Féin.[57] In the aftermath of a shooting of an RIC auxiliary on 17 June 1921, brothers John and Patrick Watters were taken from their home at the Windmill Bar and shot dead. The British authorities subsequently suppressed the Dundalk Examiner newspaper for reporting on the incident, and smashed its printing presses.[50] Volunteers from the area led by Frank Aiken were more active in Ulster, and were responsible for the derailing of a military train at Adavoyle railway station, 13 km north of Dundalk, which killed three soldiers, the train's guard, and dozens of horses.[59]

The Anglo-Irish Treaty turned Dundalk, once again, into a frontier town. In the new Irish Free State, the split over the treaty led to the Irish Civil War. Before the outbreak of hostilities, Éamon de Valera toured Ireland making a series of anti-treaty speeches. He visited Dundalk on 2 April 1922 and before a large crowd in the Market Square, he said that those who had negotiated the treaty "had run across to Lloyd George to be spanked like little boys".[60]

Frank Aiken attempted to keep his division neutral during the split over the treaty but on 16 July 1922, Aiken and all of the anti-treaty elements among his men were arrested and imprisoned at Dundalk military barracks and Dundalk Gaol in a surprise move by the pro-treaty Fifth Northern Division, now part of the National Army. On 27 July, anti-treaty 'Irregulars' blew a hole in the outer wall of the gaol, freeing Aiken and his men. On 14 August, Aiken led an attack on the barracks that resulted in its capture with five National Army and two Irregular soldiers killed. Aiken's men killed another dozen National Army soldiers in guerrilla attacks before the town was retaken without resistance on 26 August. Before withdrawing, Aiken called for a truce at a meeting in the centre of Dundalk.[61]

From that point, north Louth ceased to be an area of strategic importance in the war. Guerrilla attacks continued—mostly acts of sabotage, particularly against the railway. In January 1923, six anti-treaty prisoners were executed by firing squad in Dundalk for bearing arms against the state.[62][63]

Border town

editThe partition of Ireland turned Dundalk into a border town and the Dublin–Belfast main line into an international railway. On 1 April 1923, the Free State government began installing border posts for the purpose of collecting customs duties.[64] Almost immediately, the town started to suffer economic problems. The introduction of the border and tariffs exacerbated the effects of a global post-war slump.[65]

With a population of 14,000 at the time, unemployment was reported to be nearly 2,000 and it was reported that: "Up to a few years ago, Dundalk was one of the most prosperous and go-ahead towns in Ireland... [but] it is a matter of common local knowledge that distress to an acute degree is prevalent".[65] The Anglo-Irish trade war, in the midst of a global depression, made things more difficult still. The industrial situation stabilised, however, as the protectionist policies adopted allowed local industries to increase employment and prosper.[66]

During the Emergency (as World War II was called in Ireland), there were three aeroplane crashes in what is now the municipal district. A British Hudson bomber crashed in 1941, killing three crew, and a P-51 Mustang fighter of the US Army Air Forces crashed in September 1944, killing its pilot. The worst of the wartime air crashes occurred on 16 March 1942. 15 allied airmen died when their Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber crashed into Slieve na Glogh, which rises above the townland of Jenkinstown.[67] On 24 July 1941, the Luftwaffe dropped bombs near the town. There were no casualties and only minor damage was caused.[68]

The town continued to grow in size after the war—in terms of area, population and employment—despite economic shocks such as the dissolution of the G.N.R. in 1958.[57] The accession of Ireland to the European Economic Community in 1973, however, saw factory closures and job losses in businesses that struggled due to competition, collapsing consumer confidence, and unfavourable exchange rates with cross-border competitors. The downturn resulted in an unemployment rate of 26% by 1986.[69]

In addition, the outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland in 1968 and the town's position close to the border saw the town's population swell, as nationalists/Catholics fleeing the violence in Northern Ireland settled in the area.[70] As a result of the ongoing sectarianism in the north, there was sympathy for the cause of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and Sinn Féin, and the town was home to several IRA members.[71] It was in this period that Dundalk earned the nickname 'El Paso', after the town in Texas on the border with Mexico.[72] British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher asked Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement what his reaction would be if the British bombed Dundalk to stop the IRA from launching attacks in Northern Ireland.[73]

On 19 December 1975, a car bombing in the centre of the town carried out by the Ulster Volunteer Force killed two people and injured 15.[74][75] There were several incidents of British military incursions into North Louth. The town was also the scene of several killings connected to the INLA and its internal feuds and criminal activity.[76] On 1 September 1973, the 27 Infantry Battalion of the Irish Army was established with its headquarters in Dundalk barracks, as a result of the ongoing violence in the border region of North Louth / South Armagh. The barracks was renamed Aiken Barracks in 1986 in honour of Frank Aiken.[77]

Dundalk celebrated its 'official' 1200th year in 1989, meaning the Irish government recognised 789 as the year in which the first settlement was founded, with then President of Ireland, Dr. Patrick Hillery, attending a celebration at the Market Square.[78]

After the start of the Northern Ireland peace process, and the subsequent Good Friday Agreement, then U.S. president, Bill Clinton chose Dundalk to make an open-air address in December 2000 in support of the peace process.[79] In his speech in the Market Square, witnessed by an estimated 60,000 people, Clinton spoke of "a new day in Dundalk and a new day in Ireland".[80]

21st century

editThe town was slow to benefit from a 'peace dividend', and in the first decade of the new millennium the two Diageo-owned breweries and the Carroll's tobacco factory were among several factories to close—finally severing the links to the town's industrial past.[81][82][83] By 2012, the town was being painted as "one of Ireland's most deprived areas" after the global downturn following the Financial crisis of 2007–2008.[84]

Indigenous industry started to recover, with the Great Northern Brewery being reopened as 'the Great Northern Distillery' in 2015 by John Teeling, who had established and later sold the Cooley Distillery;[85] and locally-driven initiatives led to a flurry of foreign direct investment announcements in the latter half of the 2010s, particularly in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors.[86][87]

The town's association football club, Dundalk F.C., first formed in 1903 by the workers of the Great Northern Railway, received European-wide recognition when it became the first Irish side to win points in the group stage of European competition in the 2016–17 UEFA Europa League.[88][89]

In April 2023, Joe Biden, who has ancestry in north Louth, became the second sitting US president to visit the town.[90]

Geography

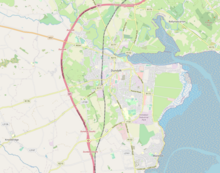

editDundalk lies on the 54th parallel north circle of latitude. It is situated where the Castletown River flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland, with the town centre on the south side of the river. It is in County Louth, which shares borders with County Armagh to the north (in Northern Ireland), County Monaghan to the west, and County Meath to the south. It is near the border with Northern Ireland (which is 7 km (4.3 mi) from the town centre by road and 3.5 km (2.2 mi) at the nearest points by air), and is equidistant between Dublin and Belfast (80 km (50 mi) from both). The town came to be nicknamed the 'Gap of the North' where the northernmost point of the province of Leinster meets the province of Ulster (although the actual 'gap' is the Moyry Pass 8 km to the north at the border with Northern Ireland).[91]

Following the abolition of 'legal towns' under the Local Government Reform Act 2014, Dundalk is part of the wider Dundalk Municipal District for the purposes of local government, which is approximately equivalent to the pre-1898 baronies of Dundalk Lower and Dundalk Upper, i.e. roughly the northern one-third of the county by area including the Cooley peninsula.[2] The former legal town and its environs (approximately the area north of the River Fane (including Blackrock), south of Exit 18 on the M1, bordered by the M1 to the west and the Irish Sea to the east; and incorporating Knockbridge to the west of the M1) is now the 'census town'.[92]

Landscape

editThe main part of the census town lies at sea level. Dún Dealgan Motte at Castletown is the highest point in the urban area at an elevation of 60 m (200 ft).[93] The municipal district includes the Cooley Mountains, with Slieve Foy the highest of the peaks at an elevation of 589 m (1,932 ft).[94]

The urban area straddles two geographical areas. A landscape of drumlins and undulating farmland form a crescent around the town's outer limits. This area contains contorted Ordovician and Silurian slates and shales. The flat, low-lying coastal plain of the main part of the urban area consists of alluvial clays, laid down as the sea retreated following the last Ice Age. Land was reclaimed both naturally and because of the drainage schemes undertaken in the 18th century by James Hamilton, the first Earl of Clanbrassil. This has meant that the topography of the district has changed extensively since the area was first inhabited and also since the formation of the original Norman settlements.[28]

Street layout

editThe layout of Dundalk is based around three principal street systems leading to the open, central Market Square. Clanbrassil Street and Bridge Street run north from the square to the bridge over the Castletown River with the Castletown Road running west from Bridge Street towards Castletown Mount—the original Norman settlement of Dundalk. Jocelyn Street, Seatown Place, and Barrack Street run east from the square towards the old Quay Street railway station, the army barracks, and the Port of Dundalk. Park Street, Dublin Street, and Hill Street run south out of the town to the Dublin Road.[39]

Climate

editSimilar to much of northwest Europe, Dundalk experiences an oceanic climate and does not suffer from the extremes of temperature experienced by many other locations at similar latitude.[95] Summers are typically cool and partly cloudy and the winter is typically cold, wet, windy, and mostly cloudy. Over the course of the year, the temperature typically varies from 2 to 19 °C (36 to 66 °F) and is rarely below −2 °C (28 °F) or above 23 °C (73 °F).[96]

| Climate data for Dundalk, Leinster | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.2 (44.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 78 (3.1) |

64 (2.5) |

65 (2.6) |

71 (2.8) |

76 (3.0) |

82 (3.2) |

83 (3.3) |

88 (3.5) |

71 (2.8) |

85 (3.3) |

85 (3.3) |

79 (3.1) |

927 (36.5) |

| Source: [97] | |||||||||||||

Demography

editDundalk is the seventh largest urban area in Ireland and the second largest town (after Drogheda), with a population of 43,112 as of the 2022 census.[3] Dundalk is the biggest town in Louth, however, because part of the census town of Drogheda is in County Meath.[2] The population density of the census town of Dundalk was measured at 1,986.4/km2 (5,145/sq mi) in 2022.[98] The population of the wider municipal district is 64,287.[4]

Population statistics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 9,256 | — |

| 1831 | 10,078 | +8.9% |

| 1841 | 10,782 | +7.0% |

| 1851 | 9,842 | −8.7% |

| 1861 | 10,360 | +5.3% |

| 1871 | 11,327 | +9.3% |

| 1881 | 11,913 | +5.2% |

| 1891 | 12,449 | +4.5% |

| 1901 | 13,076 | +5.0% |

| 1911 | 13,128 | +0.4% |

| 1926 | 13,996 | +6.6% |

| 1936 | 14,684 | +4.9% |

| 1946 | 18,562 | +26.4% |

| 1951 | 19,678 | +6.0% |

| 1956 | 21,687 | +10.2% |

| 1961 | 21,228 | −2.1% |

| 1966 | 21,678 | +2.1% |

| 1971 | 23,816 | +9.9% |

| 1981 | 29,135 | +22.3% |

| 1986 | 30,695 | +5.4% |

| 1991 | 30,061 | −2.1% |

| 1996 | 30,195 | +0.4% |

| 2002 | 32,505 | +7.7% |

| 2006 | 35,090 | +8.0% |

| 2011 | 37,816 | +7.8% |

| 2016 | 39,004 | +3.1% |

| 2022 | 43,112 | +10.5% |

| [99][92][100][101][102][3] | ||

- Population by place of birth

| Location | 2006[99] | 2011[92] | 2016[100] | 2022[103] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 28,095 | 29,114 | 29,430 | 31,283 |

| UK | 3,488 | 3,839 | 3,791 | 3,946 |

| Poland | 252 | 555 | 602 | 629 |

| Lithuania | 421 | 633 | 657 | -[c] |

| Rest of EU | 692 | 1,119 | 1,508 | 2,821 |

| Rest of World | 1,804 | 2,269 | 2,652 | 4,056 |

- Population by ethnic or cultural background

| Ethnicity or culture | 2006[99] | 2011[92] | 2016[100] | 2022[103] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Irish | 29,840 | 30,645 | 29,872 | 29,644 |

| White Irish Traveller | 325 | 441 | 535 | 674 |

| Other White | 1,802 | 2,987 | 3,572 | 4,426 |

| Black or Black Irish | 1,276 | 1,669 | 1,785 | 2,566 |

| Asian or Asian Irish | 372 | 687 | 988 | 1,431 |

| Other | 380 | 389 | 682 | 948 |

| Not stated | 757 | 711 | 1,206 | 3,226 |

- Population by religion

| Religion | 2006[99] | 2011[92] | 2016[100] | 2022[103] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 30,677 | 31,790 | 30,187 | 28,529 |

| Other stated religions | 2,472 | 3,350 | 4,248 | 5,421 |

| No religion | 1,158 | 1,971 | 3,331 | 5,566 |

| Not stated | 778 | 705 | 1,238 | 3,596 |

- Population by principal status

| Economic status | 2006[99] | 2011[92] | 2016[100] | 2022[103] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At work | 14,301 | 12,875 | 14,312 | 17,314 |

| Looking for first regular job | 424 | 412 | 463 | 523 |

| Unemployed | 1,892 | 4,238 | 3,308 | 2,347[d] |

| Student | 2,985 | 3,747 | 3,842 | 3,991 |

| Looking after home / family | 3,036 | 2,634 | 2,453 | 2,401 |

| Retired | 3,204 | 3,903 | 4,332 | 5,170 |

| Unable to work | 1,483 | 1,536 | 1,552 | 1,869 |

| Other | 95 | 121 | 112 | 282 |

Language

editThe first language of the majority of 'white Irish' residents of Dundalk is English (a.k.a. Hiberno-English). Approximately 4% of the population speak the Irish language on a daily basis outside of the education system.[99][92][100] The Omeath area in Cooley, within the municipal district, was a small Gaeltacht area, with the last speaker of a 'Louth Irish' dialect dying in 1960.[104]

Politics and government

editNational and European

editDundalk is the county town (the administrative centre) of the county of Louth in Ireland. It is represented at the national level in Dáil Éireann as part the Louth parliamentary constituency, which was created under the terms of the Electoral Act 1923, and first used at the 1923 general election.[105]

Before the Act of Union, which came into force on 1 January 1801, Dundalk was a Parliament of Ireland constituency. Following the Act of Union, Dundalk was a UK Parliament constituency until 1885. In 1885, the constituency was combined with the northern part of the County Louth constituency to become North Louth. In 1918, the North Louth constituency was combined with South Louth to form a single County Louth constituency—the precursor of the constituency formed following the creation of Dáil Éireann.[106]

Dundalk is represented in the European Parliament within the Midlands–North-West constituency.[107]

Local government

editLouth County Council (Irish: Comhairle Contae Lú) is the authority responsible for local government in Dundalk.[108] As a county council, it is governed by the Local Government Act 2001.[109] For administrative purposes, the council is sub-divided into three areas, centred around the three main towns in the county—Dundalk, Drogheda and Ardee. The Dundalk Municipal District comprises all of the county to the north of a line running approximately east-to-north west, from the coast to the Monaghan border, across the villages of Castlebellingham and Knockbridge.[110]

The county council has 29 elected members, 13 of whom are from the Dundalk district. Elections are held every five years and are by single transferable vote. For the purpose of elections, the Dundalk Municipal District is sub-divided into two local electoral areas: Dundalk-Carlingford (6 Seats) and Dundalk South (7 Seats).[111]

Coat of arms

editThe coat of arms of Dundalk was officially granted by the Office of the Chief Herald at the National Library of Ireland in 1968, and is a replication of the seal matrix of the 'New Town of Dundalk', which itself dates to the 14th century. The modern-day coat of arms contains the motto Irish: Mé do rug Cú Chulainn cróga ("I gave birth to brave Cú Chulainn"). It can be seen that the seal displays both Gaelic and Norman elements as the town developed from both origins. The shield is from the coat of arms of the de Furnivall family—a bend between six martlets. The ermine boar supporter is derived from the arms of the Ó hAnluain (O'Hanlon) family, Kings of Airthir, the main Gaelic Irish family in the area. The precise origins of the lion passant guardant and the foot soldier with his spear and sword are not known.[31] It is believed that the foot soldier is of Norman origins and is likely traced to Bertram de Verdon and his family who planned the first wall of Dundalk and the demesne when it was designed as a Norman town. The lion, being a symbol of Norman royalty, can be found on many crests and atop buildings in Dublin and many other former Norman settlements.[citation needed]

Previously, the town's coat of arms was a simpler three gold martlets on an azure field.[113] The earliest recorded use of this coat of arms is when the Corporation of Dundalk was granted a charter by Charles II in 1673.[114] It appears as the Corporation Seal in a town plan dated 1675.[115] It cannot be stated definitively if there is a link between the 14th century seal and the 17th century seal. However, another Anglo-Norman family, the Dowdalls, were also influential landowners in Dundalk in the Middle Ages,[116] and their family coat of arms contains three martlets on a field. The townland of Dowdallshill lies to the north of the Castletown River. The Corporation Seal can be seen carved in stone on Dundalk Town Hall, which was built in the mid-1800s.[117]

In December 1929, the town council proposed to remove the "three black crows" seal because it had supposedly been imposed by King Henry VIII,[118] a historically inaccurate claim that met widespread derision.[119] The majority on the town council pressed ahead and the old seal was replaced by a seal depicting Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid and Saint Colmcille in the form of a shamrock.[113]

Several companies and organisations in the town continued to use the shield with three martlets as their logo. Examples include the Dundalk Race Company Limited (the company that ran Dundalk Racecourse), the Macardle Moore and Company brewery, and Dealgan Milk Products (a dairy company formed in the town in 1960). It also became the crest of Dundalk Football Club in 1927. The club's current crest retains the three martlets but on a red shield.[120]

Economy

editIndustry

editLinen was the first industry established in Dundalk in the mid-18th century but it failed by the end of the century, with the factories becoming derelict. It would be the next century before new industries established themselves: mills, tanneries, a foundry, a distillery, and several breweries. During James Hamilton's improvements to the town during the 18th century, the Port of Dundalk was established and became the eighth largest in Ireland in terms of exports.[121][122]

The second half of the 19th century saw the population of Dundalk increase by 30% (despite the population of Ireland as a whole declining in the same period) as the town's industries thrived. The Malcolm Brown & Co. Dundalk Distillery was established c.1780 at Roden Place and operated successfully throughout the 19th century. Brewing was also a key industry in the town, with eight breweries in operation by the end of the 1830s. The famine of the 1840s left just two breweries in operation, which merged to become the Macardle Moore & Co. brewery at Cambricville. The Great Northern Brewery opened later, in 1896.[123] The Dundalk Iron Works was established in 1821 and by the end of the century had expanded to become a leading employer in the town.[124] The P.J. Carroll tobacco factory was started on a small scale in the 1820s and grew throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) works established in 1881 became the "backbone of the town".[125]

The town's industries suffered after partition and again from the Anglo-Irish trade war. The imposition of tariffs and duties in April 1923 and the establishment of customs checks on the border affected exports and trade with the Newry district, which was now in a different jurisdiction.[64] The iron works and the distillery, which the Distillers Company of Scotland had acquired in 1912, were the first major local industries to close.[126]

Protectionism gave the town's industries breathing space, and by 1950 they had recovered from the effects of partition and the trade war. The two breweries were successful and tobacco manufacturing, shoe manufacturing, and the railway works provided thousands of jobs.[127] The town was also a thriving commercial centre, as the increase in bus traffic brought shoppers in from a wide radius.[125] The Northern Ireland government's decision to close many of the G.N.R. lines north of the border, however, made the company nonviable, and it was dissolved in 1958 leading to the closure of the works in Dundalk. It was replaced by Dundalk Engineering Works Ltd (DEW)—a government-backed initiative to keep the 980 remaining workers in employment.[128] Carroll's also continued to expand and modernise, opening a new factory on the Dublin Road in 1970. The design by Ronnie Tallon of Michael Scott & Partners subsequently won architectural awards.[129]

As late as 1969, the town was still in a position to boast of its industrial prowess, with the engineering companies at the DEW prospering.[130] The pressures of trade liberalisation introduced by Ireland's accession to the EEC in 1973 caused many businesses to falter during the 1970s and 1980s. The Engineering Works closed in 1985 and the last shoemaking factory closed in 2001.[131][132] The ECCO (Electronics Components Company Overseas) factory, which had been opened by General Electric in 1966 and become the town's leading employer by 1973, employing around 1,500 people at its peak, closed in 2006 after a long period of decline.[83] Diageo closed both of the town's breweries—first Cambricville in 2001, then the Great Northern Brewery in 2013 after a decade-long wind down.[82] Also after a long decline, the Carroll's factory closed in 2005.[81]

Unemployment in the town reached 27.9% by 1991,[133] and pleas to government for assistance were unsuccessful.[134] The town was slow to benefit from the Celtic Tiger economy that saw an economic boom in Ireland from the mid-1990s and continued to suffer from business closures and job losses. By 2012, the town was being painted as one of Ireland's "most deprived areas" after the global downturn following the Financial crisis of 2007–2008.[84]

Indigenous industry started to recover following the financial crisis, with the Great Northern Brewery being reopened as 'the Great Northern Distillery' in 2015 by John Teeling, who had established the Cooley Distillery.[85] Locally-driven initiatives led to a flurry of Foreign Direct Investment announcements in the latter half of the 2010s, particularly in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors.[86][87]

Tourism

editThe Dundalk / North Louth region is marketed as part of the 'Ireland's Ancient East' campaign.[135] The 'ancient east' encompasses Ireland's coast from the border with Northern Ireland at Carlingford Lough to Kinsale in County Cork; inland as far as the River Shannon. In contrast to the Wild Atlantic Way, which focuses on landscape, the 'Ireland's Ancient East' campaign is more focused on history and heritage.[136]

Louth is marketed as the 'Land of Legends', a campaign which also refers to a "rich and ancient history and heritage" and seeks to increase the number of visitors to the region "by capitalising on County Louth's unique location within Ireland's Ancient East, as the hub for the Boyne Valley and the Cooley, Mourne and Gullion Regions".[137] Dundalk is home to Ireland's tallest mural, which depicts the warrior god Lugh. It is situated on the Gateway Hotel, Dundalk and measures 41 metres in height.[138]

Transport

editShipping

editDundalk Port is a cargo import and export facility. There is no passenger traffic.[139]

Shipping services to Liverpool were provided from 1837 by the Dundalk Steam Packet Company. It took over its rivals to become the Dundalk and Newry Steam Packet Company, which shipped cargo, live animals and passengers. It was forced to go into liquidation and allow itself to be taken over by B&I in 1926 following a series of strikes. B&I maintained the Dundalk to Liverpool route as a weekly service until 1968.[140]

Railway

editDundalk is the closest station to the border on the southern side along the Belfast–Dublin line. The first railway links arrived when the Dundalk and Enniskillen Railway opened a line from Quay Street to Castleblayney in 1849, and by 1860 the company operated a route northwest to Derry. The line to Quay Street was later extended to Newry and Greenore by the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway.[141]

Also in 1849, the Dublin and Belfast Junction Railway opened its first station in Dundalk. Following a series of mergers, both the Dublin and Belfast and Dundalk and Enniskillen lines were incorporated into the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) in 1876.[44] After partition, the G.N.R. had a border running through its network, with lines crisscrossing it several times, and the Northern Ireland government wanted to close many of the lines in favour of bus transport. By the 1950s, the G.N.R. company had ceased to be profitable and Dundalk saw its secondary routes closed—first the line to Greenore and Newry in 1951,[142] and then the line to Derry in 1957.[143] The G.N.R. was nationalised on both sides of the border in 1953, and the company was finally dissolved in 1958. The closure of the G.N.R. left Dundalk with only one operational line—the Dublin–Belfast "Enterprise" service (as well as commuter services to and from Dublin).[144]

The G.N.R. built the current Dundalk railway station in 1894. It was renamed Clarke Station in 1966, in commemoration of Tom Clarke, one of the executed leaders of the Easter Rising. It houses a small museum in the old first-class waiting room, and has been called, "the finest station on the main Dublin–Belfast line".[145] It was used as a filming location for the Walt Disney Pictures film, Disenchanted in May 2021.[146]

Bus

editDundalk's Bus Station is operated by Bus Éireann and is located on the Long Walk near the town centre. The company runs a town service—Route 174.[147] It also operates routes from Dundalk to Dublin, Galway, Newry, Clones, Cavan, and towns in between.[148]

The Dundalk-Blackrock route was one of very few bus routes not compulsorily purchased by CIÉ under the Transport Acts of 1932 and 1933.[149] It has been operated by Halpenny Travel since 1920.[150]

Road

editThe M1–N1/A1 connects Dundalk to Dublin and Belfast. Exits 16, 17, and 18 service Dundalk South, Dundalk Centre, and Dundalk North, respectively. The National Secondary Road N52 from Nenagh, County Tipperary travels through the junction for Exit 16 on the M1, runs through the east side of the town, and terminates at the junction for Exit 18 of the M1. The N53 from Castleblayney, County Monaghan, which crosses the border twice, terminates at the junction for Exit 17 on the M1. The R173, which starts and finishes at the junction for Exit 18 of the M1, connects the town to the Cooley peninsula. The R171 connects the town to Ardee, the R177 and A29 connect the town to Armagh, and the R178 connects the town to Virginia, County Cavan via Carrickmacross, Shercock, and Bailieborough.[151]

Architecture

editMany of the buildings of architectural note in the town were built during the 19th century.[43] Several buildings on the streets off the Market Square are described as being in the "Dundalk style" —ornate buildings, "testifying to the confidence of Dundalk's merchant class in the latter part of the 19th-century".[152]

The Courthouse (completed in 1819) was designed by Edward Parke and John Bowden in the Neoclassical style and modelled on the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens.[153] The Maid of Erin statue, erected in 1898, is located in the Market Square in front of the Court House.[154] The adjacent Town Hall (completed in 1865), is an elaborate Italianate Palazzo Townhall, originally designed by John Murray as a corn exchange. It was sold to the Town Commissioners on completion and now houses An Táin Arts Centre, which comprises a 350-seat main theatre, a 55-seat studio theatre, a visual arts gallery, and two workshop spaces.[155][117]

The Kelly Monument is in nearby Roden Place, in front of St Patrick's Church. In 1858, a ship called the Mary Stoddart, was wrecked in Dundalk Bay during a storm. While attempting to rescue the crew, Captain James Joseph Kelly and three volunteer crew drowned when the storm overturned their boat. Five of the Mary Stoddart crew also drowned and 11 were eventually rescued. The monument in Roden Place was erected 20 years later as a memorial.[156][157][158] The Louth County Library is located off Roden Place, in a restored building of what was the Dundalk Distillery.[159] Further up Jocelyn Street, the County Museum Dundalk, documenting the history of County Louth, is housed in another restored building of the former distillery.[160]

Dundalk Gaol was completed in 1855 and closed as a gaol in the 1930s. It was designed by John Neville, who was the county engineer at the time.[161] The Governor's House to the front of the Gaol became the Garda Station, and the two prison wings were later restored and divided between the 'Oriel Centre' and the Louth County Archive.[162][163] The neighbouring Louth County Infirmary (completed in 1834) was designed by English architect Thomas Smith in a neo-Tudor style with a central entrance-way flanked by two recessed ground floor arcades. It was purchased by Dundalk Grammar School in 2000.[164]

The two oldest buildings in the town centre are Saint Nicholas's Church of Ireland church and Seatown Castle. Saint Nicholas's was built c. 1400. It comprises elements of 14th- 17th- and 18th-century church buildings, having been extended, damaged, rebuilt over the centuries, and finally reworked by Francis Johnston.[165] It is known locally as the Green Church due to its green copper spire. It contains an epitaph erected to the memory of Scotland's National Bard, Robert Burns. His sister, Agnes Burns, is buried in the church's graveyard.[166] Seatown Castle is at the junction of Mill Street and Castle Street. It is part of what was a Franciscan friary originally founded in the 13th century. A baptismal font in St. Nicholas's is reputed to have come from the friary.[167]

Further out from the town centre are Dún Dealgan Motte and Castle Roche. The former is also known as Cú Chulainn Castle and Byrne's Folly and is a national monument. It sits on the site of the manor house built in the late 12th century by Bertram de Verdun when the Normans reached the area. A local pirate named Patrick Byrne built the castellated house now located on the site.[168] Castle Roche was built by Bertram's granddaughter, Roesia, and completed by her son, John, in the late 13th century.[169]

A 20th century construction, which has won architectural awards, is the Carroll's tobacco factory on the Dublin Road. It has been called "a groundbreaking Irish factory design".[129][170] The design, by Ronnie Tallon, is in the Miesian idiom. The first of the Louis le Brocquy Táin illustrations was commissioned for the factory. It became part of the Dundalk Institute of Technology campus in the 2010s. The 'sails' sculpture to the front was designed by Gerda Frömel.[171]

Many of the churches in the town were also built in the 19th century, including the Presbyterian church (1839), the former Methodist church (1834), and the Roman Catholic churches of St Patrick (1847), St Malachy (1862), St Nicholas (1860), and St Joseph (1890).[43] St Patrick's was designed by Thomas Duff, and modelled on King's College Chapel, Cambridge. It was completed in 1847. Duff also designed the Presbyterian church on Jocelyn Street.[172] The bell tower at St Patrick's was added in 1903, modelled by George Ashlin on that of another English church, Gloucester Cathedral.[173] Ashlin also designed the granite-built St Joseph's Redemptorist monastery and church (finished in 1880 and 1892, respectively).[174]

Public spaces

editThe largest park in the town centre is Ice House Hill. It is approximately 8 hectares (20 acres). The site was once part of Dundalk House demesne (the stately home of the Earl of Clanbrassil). Dundalk House itself was demolished in the early 20th century to make way for an extension of the original P.J. Carroll tobacco factory.[91] The original Ice House, built c. 1780, remains in the park and can be viewed from the outside.[175] The smaller St. Helena Park is approximately 0.7 hectares (1.7 acres) and was first laid out in the 1800s. The bandstand was erected in the early 1920s. Most of the land which the park is on was reclaimed from the Castletown River.[176] St Leonard's Garden in Seatown is a small park restored in the 1960s from a cemetery that was closed in 1896 and allowed to become overgrown. Within the park are the ruined remains of stone walls from the friary founded by Bertram de Verdun in the 12th century.[177]

The Navvy Bank (from 'navigator') is an artificial embankment constructed in the 1840s to facilitate the entry of shipping to Dundalk Port. It is approximately two km (1.2 mi) long and runs from Soldiers Point at the entrance to Dundalk Harbour, to near the present-day quay. It is now a public walkway. Along its route, there is a memorial to those who died in the sinking of the S.S. Dundalk during World War I.[54] At Soldiers Point there is a bronze sculpture called The Sea God Managuan and Voyagers after a Celtic god of the sea.[178]

Adjacent to the town of Dundalk is the village of Blackrock (five km (3.1 mi) from the town centre), which has three public beaches. Blackrock was a fishing village before it became popular as a resort destination in the late 19th century.[179] The promenade and sea wall, originally built in 1851, run along the length of the main beach and main street of the village. There are wetlands on both the north and south sides of the village, which are wildlife sanctuaries.[180] In 2000, to mark the millennium year, a sundial / statue was erected in Blackrock on the promenade. The 3 m (10 ft) high gnomon is a bronze sculpture of a female diving figure, which was subsequently named 'Aisling'.[181]

Seven km (4.3 mi) to the south-west of the town, between Haggardstown and Knockbridge, is Stephenstown Pond—a nature park. It was originally commissioned by Matthew Fortescue, owner of the nearby Stephenstown House, which is in ruins. It was designed by William Galt, husband of Agnes Burns.[182]

Eleven km (6.8 mi) to the north of the town, within the municipal district, is Ravensdale Forest. It is mixed woodland rising steeply to the summit of Black Mountain, rising 510 m (1,670 ft), with many kilometres of forest roads and tracks. There are three way-marked trails in the forest, the Táin Trail, the Ring of Gullion and the shorter Ravensdale Loop. It is managed by the Irish Forestry Service, Coillte.[183]

Education

editPrimary schools

editThere are over 20 primary schools in Dundalk including some Irish language-medium schools (Gaelscoileanna) like Gaelscoil Dhún Dealgan.[184] The largest schools in the area include Muire na nGael National School (also known as Bay Estate National School) and Saint Joseph's National School, which (as of early 2020) had an enrolment of over 670 and 570 pupils respectively.[185][186][187]

Secondary schools

editSecondary schools in the town include Coláiste Lú (an Irish medium secondary school or Gaelcholáiste),[188] De la Salle College, Dundalk Grammar School, St. Mary's College (also known as the Marist), O'Fiaich College,[189] Coláiste Rís, St. Vincent's Secondary School,[190] St. Louis Secondary School, and Coláiste Chú Chulainn.[191]

Tertiary education

editDundalk Institute of Technology (abbreviated to DkIT) is the focal point for higher education and research on the Belfast-Dublin corridor, serving the North Leinster, South Ulster region.[192] It was established in 1970 as the Regional Technical College, offering primarily technician and apprenticeship courses.[193]

The Ó Fiaich Institute of Further Education also offers further education courses.[194]

Culture

editMusic and arts

editDundalk has two centres for the arts—An Táin Arts Centre, an independent arts space in the former Táin Theatre, Town Hall, Crowe Street;[155] and The Oriel Centre in the former Dundalk Gaol, a regional centre for Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. The Oriel Centre is a resource centre and performance space, and has facilities for teaching, archives, recording, rehearsal, and performance.[195] The Spirit Store, located at George's Quay in the Port of Dundalk, is a gig venue in the town.[196][197]

Dundalk Institute of Technology Department of Creative Arts, Media and Music has several groups and ensembles, including the Ceol Oirghiallla Traditional Music Ensemble, the DkIT Choir, the Music Theatre Group, the Oriel Traditional Orchestra, and the Fr. McNally Chamber Orchestra.[198]

The Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland (CBOI) is a youth orchestra based at Coláiste Chu Chulainn, Dundalk. It was started as a peace initiative. Since 1996, it has toured internationally and has played at venues such as Carnegie Hall and the Royal Albert Hall.[199] The Dundalk Brass Band was established in 1976 and performs a cross-section of big band and brass music.[200]

Festivals

editThe Dundalk Show (also known as the Dundalk Agricultural Show and the County Louth Agricultural Show) has run since the 19th century. It was originally held at the Dundalk racecourse in Dowdallshill, before moving to the Fair Green, the grounds of St Mary's College, Bellingham Castle, and latterly Bellurgan Park.[201]

Other festivals / events in the town include the Frostival winter festival, which is held at the end of November, and an urban art festival called 'Seek Dundalk'. Street murals painted as part of Seek include Edward Bruce, the engineer Peter Rice, and Cú Chulainn.[202][203][204]

Within the wider Dundalk Municipal District, festivals and events also include the All-Ireland Poc Fada Championship held every year since 1960 on Annaverna Mountain on the Cooley Peninsula,[205] and the Brigid of Faughart Festival.[206]

The St. Gerard Majella Annual Novena is an annual religious festival held over nine days in St. Joseph's Redemptorist Church in Dundalk. It runs in October.[207] A patron takes place on 15 August at Ladywell Shrine, during the Feast of the Assumption.[208] The Seatown Patron is held annually on 29 June (the feast day of Saint Peter, who is the patron saint of Seatown).[209] The patron is celebrated by night-time bonfires, which is a tradition believed to have originated in medieval times.[210]

The Dundalk Maytime Festival was the town's largest festival and ran for 40 years starting in 1965. It started out as a 'Grape and Grain' festival before later centring around amateur drama. It eventually ceased because of difficulties in securing sponsorship.[211]

Twin towns

editDundalk is twinned with the following towns:

- Rezé, France (1990).[212]

- Pikeville, Kentucky, United States (2015)[213]

Sport

editDundalk Football Club is a professional association football club. The club competes in the League of Ireland Premier Division, the top tier of Irish football. The club was founded in 1903 as Dundalk G.N.R., the works-team of the Great Northern Railway.[214] They were a junior club until they joined the Leinster Senior League in 1922–23.[215] They were elected to the Free State League (which later became the League of Ireland) in 1926–27.[216][217] The club has played at Oriel Park since moving from its original home at the Dundalk Athletic Grounds in 1936.[218]

Gaelic football clubs in the town include Dundalk Gaels GFC, Seán O'Mahony's GFC, Clan na Gael, Na Piarsaigh, Dowdallshill and Dundalk Young Irelands.[219] Young Irelands (representing Louth) contested the first All-Ireland football final in 1888, losing to the Commercials club, representing Limerick.[220]

The two hurling clubs in the town are Knockbridge GAA and Naomh Moninne H.C., who are the leading club in Louth with 22 county titles as of 2020.[221] A founding member of Naomh Moninne, Father Pól Mac Sheáin, introduced the All-Ireland Poc Fada Championship in 1960.[222]

Dundalk R.F.C. is an amateur Irish Rugby football club who compete in the Leinster League. The club first formed in 1877 and became founder members of the Provincial Towns Union, which then merged into what became the Northern Branch of the Irish Rugby Football Union. They moved to their present home ground at Mill Road in 1967.[223]

The Dundalk Racecourse was reopened as Dundalk Stadium in 2007 and now holds both horse racing and greyhound racing meetings. It is Ireland's first all-weather horse racing track. The stadium also hosts the Dundalk International greyhound race.[224]

Golf was first played in Dundalk when a nine-hole course was laid out at Deer Park in 1893. The Dundalk Golf Club was founded in December 1904 at Deer Park, then moved to its present location in Blackrock in 1922. The current layout was designed by Peter Alliss and completed in 1980.[225] The Ballymascanlon Hotel also has a parkland course.[226] Greenore Golf Club (which is within the municipal district) was opened in October 1896 by the London and North Western Railway company, who owned a hotel in Greenore and the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway. The members bought the club when the railway company closed the line and pulled out of Ireland. The modern course layout was designed by Eddie Hackett.[227]

Dundalk has several game angling waters including the Dee, Glyde, Fane, Ballymascanlan and Castletown rivers. All these rivers flow into the Irish sea at Dundalk Bay. The rivers contain wild brown trout as well as salmon and sea trout.[228] There is a Salmon Anglers Association and a Brown Trout Anglers Association.[229] Sea Angling is available in several locations in the wider Municipal District and there is also a Sea Angling Club.[230]

The Dundalk Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club was established in 1913. It is located at the Ramparts in the town centre. The club has nine tennis courts, two Olympic-standard badminton courts and two squash courts.[231] A Dundalk and District Snooker League has been active since the 1940s. It was re-branded as the Dundalk Snooker League in 2010 and plays in the Commercial Club in the town centre.[232] The amateur boxing club, Dealgan ABC, was founded in 1938.[233] The first Dundalk Cricket Club was established in 1853 and the current club was formed in 2009. They play in Hiney Park, the former Dundalk F.C. training ground.[234]

There are several athletics clubs, including St. Gerard's A.C., St. Peter's A.C, Dun Dealgan A.C. and Blackrock A.C.,[235] and a triathlon club (Setanta Triathlon Club).[236] Cuchulainn Cycling Club was formed in 1935.[237]

The Louth Mavericks American Football Club is based in Dundalk and was established in 2012. They play in AFI Division 1, train at DKIT, and play their matches at Dundalk Rugby Club.[238]

Media

editDundalk's local newspapers are the Dundalk Democrat (established as the Dundalk Democrat and People's Journal in 1849),[239] The Argus (established as the Drogheda Argus and Leinster Journal in 1835),[240] and the Dundalk Leader, a freely distributed newspaper.[241] Online-only news media include Louth Now.[242]

There are no local or regional television services. In radio, Dundalk is serviced by regional stations LMFM (Louth-Meath FM) on 96.5 FM,[243] and iRadio (NE and Midlands) on 106.2 FM.[244] The local radio station is Dundalk FM, broadcasting on 97.7 FM.[245]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ 80 legal towns were abolished under the Local Government Reform Act 2014. Census towns which previously combined legal towns and their environs have been newly defined using the standard census town criteria (with the 100 metres proximity rule). For some towns the impact of this has been to lose area and population, compared with previous computations. 2011 census data for the 80 legal towns and their environs is available separately in table CD109.[1]

- ^ The rural area is defined as being the Dundalk Municipal District, created under the Local Government Reform Act 2014.[2]

- ^ data not specified in CSO report for Census 2022

- ^ total of 'short-term unemployed' and 'long-term unemployed'

References

edit- Bibliography

- Gosling, Paul (1991). "From Dún Delca to Dundalk: The Topography and Archaeology of a Medieval Frontier Town A.D. c. 1187-1700". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 22 (3): 221–353. doi:10.2307/27729714. JSTOR 27729714.

- Hall, Donal (2010). "Partition and County Louth". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 27 (2): 243–283. JSTOR 41433023.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. ISBN 1297871308.

- McQuillan, Jack (1993). Railway Town : The Story of the Great Northern Railway Works and Dundalk. Dundalgan Press. ISBN 0852211201.

- Oram, Hugh (2006). Old Dundalk and Blackrock. Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 978-1840333756.

- O'Sullivan, Harold (1997). Dundalk and North Louth: Paintings and Stories from Cuchulainn's Country. Dundalgan Press. ISBN 978-1900935067.

- Sexton, Daniel (2020). Dundalk Football Club: In Black And White. Amazon. ISBN 979-8639712814.

- Citations

- ^ "CD109: Population by Sex, Legal Town and Environs 2011". cso.ie. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 1 Report 2018" (PDF). housing.gov.ie. p. 77. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "F1015: Population and Average Age by Sex and List of Towns (number and percentages), 2022". Census 2022. Central Statistics Office. April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Census 2022 Population Density and Area Size". cso.ie. Central Statistics Office. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "Dundalk". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Gosling 1991, p. 243.

- ^ McEnery, M.J. (1916). Mills, James (ed.). Calendar of the Gormanston register. University press, for the Royal society of antiquaries of Ireland.

- ^ Armit, Ian; England), Prehistoric Society (London; Belfast, Queen's University of (1 January 2003). Neolithic Settlement in Ireland and Western Britain. Oxbow Books. p. 34.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Harold (1 January 1997). Dundalk and North Louth: Paintings and Stories from Cuchulainn's Country. Dundurn. ISBN 9781900935067. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pearson, Michael Parker (1 January 1993). English Heritage book of Bronze Age Britain. B.T. Batsford. ISBN 9780713468014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Holdings: Excavations at Aghnaskeagh, County Louth, Cairn A." 1935. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Evans, E. Estyn (1 January 1937). "Excavations at Aghnaskeagh, Co. Louth, Cairn B: Irish Free State Scheme of Archæological Research". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society. 9 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/27728454. JSTOR 27728454.

- ^ Kinsella, Thomas (1969). The Táin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192810901.

- ^ "St Brigid: 5 things to know about the iconic Irish woman". rte.ie. RTÉ. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Gaeilgeoirí Gather At Faughart". rte.ie. RTÉ. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "St Brigid of Kildare". victoriasway.eu. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Thornton, David E. (1997). "Early Medieval Louth: The Kingdom of Conaille Muirtheimne". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 24 (1): 139–150. doi:10.2307/27729814. hdl:11693/48560. JSTOR 27729814.

- ^ "Áed Rón". DICTIONARY OF IRISH BIOGRAPHY. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Keating, Geoffrey (1857). O'Mahony, John (ed.). Foras Feasa ar Éirinn. New York: P.M. Haverty. pp. 536–542. ISBN 1166340961.

- ^ "Five Louth Souterrains". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 19 (3): 206–217. 1979. JSTOR 27729482.

- ^ D'Alton 1864, p. 79.

- ^ "The Amazing Tale of Bailé, the Sweet-Spoken Son of Buan". IrishImbas. 22 July 2019. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "How did Seatown get its name?". Dundalk Democrat. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Standing On Cuchullain's Dun". An Claidheamh Soluis. 26 June 1915. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Connolly, S.J. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

- ^ Gosling 1991, p. 249.

- ^ a b Flood, W. H. Grattan (29 March 1899). "The De Verdons of Louth". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 9 (4): 417–419. JSTOR 25507007.

- ^ a b Gosling 1991, p. 237.

- ^ "Castle Roche, Co. Louth". archiseek.com. 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Joyce, Patrick. "A Concise History of Ireland". libraryireland.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Coat of Arms (crest) of Dundalk". heraldry-wiki.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b Gosling 1991, p. 293.

- ^ D'Alton 1864, p. 64.

- ^ Gosling 1991, p. 286.

- ^ Curran, Arthur (1971). "The Priory of St. Leonard, Dundalk". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 17 (3): 136. doi:10.2307/27729277. JSTOR 27729277.

- ^ O'Neill, James (2017). "Breaking the heart of Tyrone's rebellion? A reassessment of Mountjoy's first campaigns in Ulster, May-November 1600". Duiche Neill: The Journal of the O'Neill Country Historical Society. 24: 18–37.

- ^ a b c O'Sullivan, Harold (1977). "The Cromwellian and Restoration Settlements in the Civil Parish of Dundalk, 1649 to 1673". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 19 (1): 24–58. doi:10.2307/27729438. JSTOR 27729438.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas; Jeffrey, Keith (1996). A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521629898.

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, Harold (1961). "Two Eighteenth-Century Maps of the Clanbrassil Estate, Dundalk". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society. 15 (1): 57. doi:10.2307/27729008. JSTOR 27729008.

- ^ "Freehold of Dundalk sold at auction". The Irish Times. 22 July 2006. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, Harold (1998). "The Background to and the Events of the Insurrection of 1798 in Dundalk". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 24 (2): 31. doi:10.2307/27729828. JSTOR 27729828.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas. "The 1798 Irish Rebellion". BBC. BBC. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Dundalk". archiseek.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b McQuillan, Jack (1993). Railway Town : The Story of the Great Northern Railway Works and Dundalk. Dundalgan Press. ISBN 0852211201.

- ^ a b Wilson, Maureen (1983). "Dundalk Poor-Law Union Workhouse: The First Twenty-Five Years, 1839-64". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 20 (3): 190–209. doi:10.2307/27729565. JSTOR 27729565.

- ^ Mulligan, John (30 May 2020). "Famine graveyard is no longer forgotten part of our history". The Argus. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "The Dundalk Demonstration". Dundalk Democrat. 8 January 1881. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "The Victory in North Louth". Dundalk Democrat. 5 December 1885. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Don (2014). "John Johnston, 1846-1913". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 28 (2). JSTOR 24612659.

- ^ a b "History of national organisations Dundalk 1907-1921" (PDF). militaryarchives.ie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Carolan, Joseph (4 May 1963). "History of Dundalk". The Argus. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Funds for Dundalk World War 1 memorial". The Argus. 19 May 2018. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Dundalk, Co Louth: Ambulance Train". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b "SS Dundalk torpedoed on return from Liverpool". www.rte.ie. 20 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Ailbhe. "The 1916 Rising in Louth". theirishstory.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Louth Election Echoes". Dundalk Democrat. 4 January 1919. p. 6. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.