The video store that turned Quentin Tarantino into a director

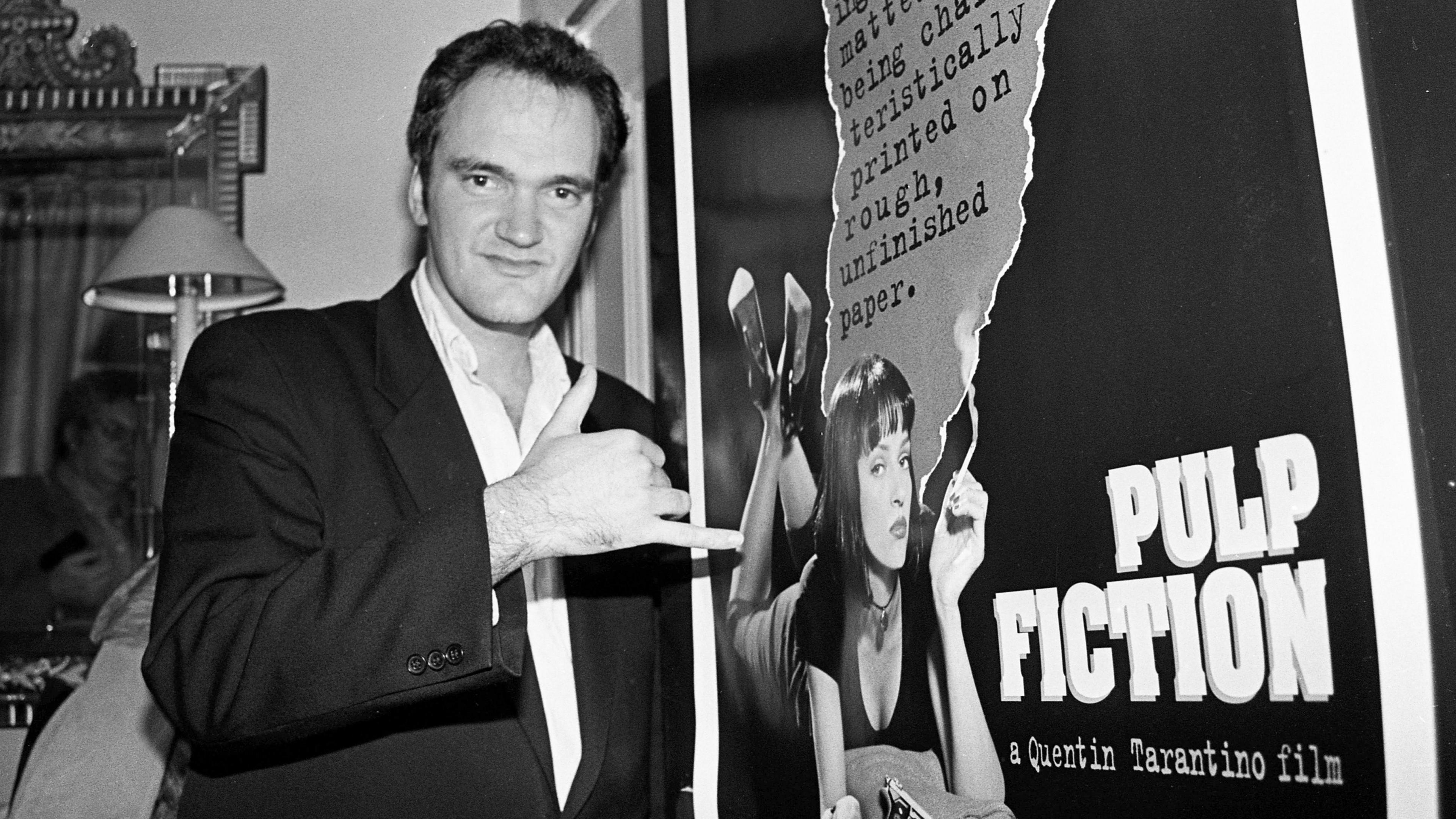

Director Quentin Tarantino standing by a poster for Pulp Fiction in London in 1994.

- Published

His years working as a video rental store clerk were pivotal in transforming Quentin Tarantino from a film geek to a Hollywood auteur, the Pulp Fiction director told the BBC.

The director was being interviewed in 1994 for the BBC’s Quentin Tarantino: Hollywood's Boy Wonder, a programme to coincide with the release of his latest movie Pulp Fiction – which marks its 30th anniversary this month. The documentary was examining his sudden rise to being one of Hollywood’s most influential film-makers despite the fact that he had no formal training in directing, screenwriting or film production.

Tarantino said that working at the Video Archives store in Manhattan Beach, California was transformational. It was more than just a job. It was a film school.

The Pulp Fiction director says that for film geeks "opinion is everything".

In 1983, he was taking acting classes while working various jobs to support himself, when he discovered the store. Owned by Lance Lawson, Video Archives was renowned for its extensive video rental collection which held everything from mainstream Hollywood fare to obscure cult classics.

“It really was a movie lover’s heaven. It was really terrific,” Tarantino told the BBC.

He would frequently visit the store to indulge his various cinema obsessions from French New Wave cinema to Italian Giallo films, animatedly chatting with Lawson about different films they liked.

“I was a customer there and I really liked it and eventually [Lawson] asked me if I wanted a job and I was ‘yeah, I’d love a job here. That would be a dream’. And it was,” he said.

Tarantino had been an obsessive film fan from an early age. Growing up in suburban Los Angeles, his single mother’s work as a nurse meant that the young Tarantino spent much of his childhood alone watching TV, listening to records or reading his comics. Finding school difficult, he would often skip classes so he could indulge his real passion, movies.

By the time he had dropped out of high school he knew he wanted to work in cinema and his job at Video Archives would prove to be an unconventional education in movie-making for him.

“This was one of the few places Quentin could come as a regular guy and get a job and become like a star," his former Video Archives co-worker Jerry Martinez told the BBC. “Because he was like the star of the store.”

Jerry Martinez (left), Quentin Tarantino (centre) and Lance Lawson (right) reminisce about working at Video Archives.

The job gave Tarantino access to Video Archives’ diverse collection of thousands of films, which he devoured with a passion. He didn’t just passively watch the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone or the grindhouse films of the 1970s, he dissected them scene by scene. He immersed himself in the world of cinema, watching the same film multiple times, scrutinising the camera shots, analysing its narrative structure and picking apart what made its dialogue sing. He spent hours soaking up the art of storytelling while sharpening his own cinematic sensibility.

“The thing about film geeks is they have an intense love for film. An incredible love for film, an incredible passion, they devote a lot of time, they devote a lot of money and they devote a lot of their life to the following of film. But they don’t really have that much to show for all this devotion, other than a movie poster collection or a still collection.

“The one thing that they do have to definitely show for it, is they have their opinion,” said Tarantino.

It was at Video Archives that Tarantino first met co-worker Roger Avary, who had his own dreams of working in the movie business. In between shifts, the pair would work on their own scripts, allowing the films they had recently watched to influence their own writing and swap notes on each other's work. The two would end up writing the script for Pulp Fiction together.

Pulp Fiction, Tarantino’s take on the popular crime stories of the 1950s, is packed full of references to other movies.

Video Archives was a mecca for all manner of film buffs and it was an environment Tarantino thrived in. He became known for fervently, and often forcefully, recommending films to store patrons, some of whom were already working in Hollywood.

He would enthusiastically recount scenes to them, engaging in long discussions about the intricacies of certain movie plot points or the nuances of different characters.

“A customer [could] come into the store and he could ask me about an obscure film and I might be able to tell the year it was directed, who directed it and maybe who the leads were,” said owner Lawson.

“Quentin would go on to tell you who the supporting cast was, who the DP [director of photography] was, who wrote the screenplay and probably do a couple of scenes from the film with the dialogue verbatim, that’s the difference between Quentin and I.”

“Video Archives was a very relaxed atmosphere. They had popcorn available. So I’m a popcorn fan and I would eat popcorn and chat with Quentin,” film and TV producer John Langley told the BBC In 1994.

“I always got a kick out of talking with Quentin because he was always so opinionated about everything under the sun.”

These discussions with fellow film obsessives were instrumental in honing Tarantino’s critical eye and teaching him to trust his instincts when it came to film. They also cultivated in him the ability to persuasively articulate to someone else what made a movie great. As a store clerk he would effectively ‘pitch’ movies he thought were good to customers. This was critical for preparing him for Hollywood.

“What you find out fairly quickly in Hollywood is this is a community where hardly anybody trusts their own opinion. People want people to tell them what is good, what to like, what not to like,” said Tarantino.

“Now here I came, alright I’m a film geek. My opinion is everything, alright. You can all disagree with me, I don’t care alright. I know I’m right as far as I’m concerned and I’ll argue anybody down.“

His exposure to such a wide range of cinema imbued Tarantino with a distinct cinematic vocabulary which would shape his later films. His movies constantly reference other films – for example the opening shot of his 1997 Blaxploitation film, Jackie Brown, mirrors an early shot in Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967). But rather than feeling derivative, in Tarantino’s films this amalgamation of different genres, film influences and pop culture feels fresh and original.

Quentin Tarantino outside the original site of the Video Archives store in Manhattan Beach, California.

A prime example of this is his Oscar-winning black comedy Pulp Fiction. The film is Tarantino’s take on the popular crime stories of the 1950s and is packed full of references to other movies.

There is a scene in the movie where mob enforcer Vincent Vega (John Travolta) sits down at a booth in the restaurant with his boss’ wife Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman). One of Mia’s early lines ‘could you roll me one of those, cowboy?’ is taken almost directly from Howard Hawks’ screwball comedy His Girl Friday (1940).

When they get up and start dancing to Chuck Berry’s You Never Can Tell, the scene homages Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 French New Wave classic Bande à Part – the poster of which is behind the director during the BBC interview – where characters spontaneously dance in a café.

Tarantino’s love for cinema is visible in every frame of his movies. His films both pay tribute to and subvert different genres and tropes, as seen in his two-part revenge movie Kill Bill (2003) which borrows and blends from martial-arts epics, samurai films and westerns. This mix and match of influences has become a hallmark of his cinema style.

So distinctive is his work, that now if a movie was described as Tarantino-esque, viewers would naturally expect a genre-bending film, powered by an eclectic soundtrack, infused with pop culture references, stylised violence, non-linear plots and unapologetic profanity-laden rapid-fire dialogue.

Tarantino has openly acknowledged the role his time working at Video Archives played in making him the director he is today. When it closed in 1995, he purchased its entire library and used it to rebuild the store in his home.

In 2022, he joined his former collaborator and store co-worker Avary in a series called The Video Archives Podcast, where they rewatched and discussed movies like they used to when they both worked behind the counter at the store.

Tarantino said: “Until I became a director, it was the best job I’d ever had.”

Explore more

- Published4 April

- Published12 August

- Published29 August

- Published25 June