Quetzalcóatl

| Quetzalcóatl | |

|---|---|

| Membro da Tezcatlipocas | |

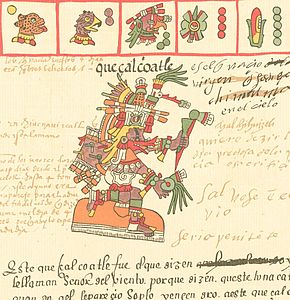

Quetzalcóatl representado no Codex Borbonicus. | |

| Outros nomes | Tecatlipoca Branco, Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Serpe Emplumada, Precioso xemelgo, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli[2] |

| Centro de culto | Templo da Serpe Emplumada, Teotihuacán, Tenochtitlán |

| Morada | Ilhuicatl-Teteocan (Décimo segundo ceo)[1] Ilhuicatl-Teoiztac (noveno ceo)[1] o oeste[1] |

| Planeta | Venus (estrela da mañá) |

| Símbolos | Serpe emplumada[1] |

| Xénero | Masculino |

| Rexión | Mesoamérica |

| Grupo étnico | Aztecas, tlaxcaltecas, toltecas (Nahoa) |

| Festivais | Teotleco |

| Información persoal | |

| Pais | Ometecuhtli e Omecihuatl (Codex Zumarraga)[1] Mixcoatl e Chimalma (Codex Chimalpopoca)[1] |

| Irmáns | Tezcatlipoca, Xipe-Totec, Huitzilopochtli (Codex Zumarraga)[1] Xolotl (Codex Chimalpopoca)[1] |

| Fillos | Ningún |

| Equivalentes | |

| Equivalente maia | Kukulkan |

Quetzalcóatl (en náhuatl: Quetzalcōātl) é unha divindade das culturas mesoamericanas, venerado principalmente polos aztecas e os toltecas. O seu nome significa "serpe emplumada" e provén do náhuatl quetzalli, “pluma do paxaro quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno)”, e coatl, “serpe”).[3] É identificado por algúns investigadores como a principal deidade do panteón centro-mexicano precolombiano.

Historia

[editar | editar a fonte]Os aztecas incorporaron esta deidade coa súa chegada ao val de México, no entanto modificaron o seu culto, eliminando algunhas partes, como a prohibición dos sacrificios humanos. Especúlase que a orixe desta deidade provén da cultura olmeca, aínda que a súa primeira aparición inequívoca ocorreu en Teotihuacán. A cultura teotihuacana dominou durante séculos o planalto mexicano. As súas influencias culturais abarcaron gran parte de Mesoamérica, incluíndo as culturas maia, mixteca e tolteca. Os maias nomearon a Quetzalcóatl como Kukulkán.

Quetzalcóatl representa as enerxías telúricas que ascenden, de aí que sexa representado como unha serpe emplumada. Neste sentido, representa a vida, a abundancia da vexetación, o alimento físico e espiritual para o pobo ou o individuo que procura un ascenso espiritual.

Posteriormente, pasou a ser venerado como deus representante do planeta Venus, simultaneamente Estrela da Mañá e Estrela da noite, correspondendo, co seu xemelgo Xolotl, á noción de morte e resurrección. Deus do Vento e Señor da Luz, era, por excelencia, o deus dos sacerdotes. É ás veces confundido co rei sacerdote de Tollan-Xicocotitlan.

Segundo fontes incertas e tradicións orais, unha das representacións deste deus é un home branco, con barba e de ollos claros. Esta representación sería un dos motivos da teoría de que os pobos indíxenas, durante a conquista da Nova España (Mesoamérica), creron que Hernán Cortés era Quetzalcóatl. O académico multiculturalista Serge Gruzinski, analizando as crónicas do século XVI sobre a conquista de México, considera que os aztecas realmente pensaron que Cortés era Quetzalcóatl e esa é unha das razóns pola que os españois dominaron tan facilmente a América Central. Os aztecas crían na volta de Quetzalcóatl e iso contribuíu positivamente no seu contacto cos españois, pensando que foran enviados polo deus.

Galería de imaxes

[editar | editar a fonte]- Galería de imaxes de representacións de Quetzalcóatl

-

Templo da Serpe Emplumada en Xochicalco.

-

Quetzalcóatl no Códice Telleriano-Remensis.

-

A serpe emplumada nas grutas de Juxtlahuaca da cultura olmeca.

-

Busto en pedra de Quetzalcóatl no templo de Teotihuacán.

-

Quetzalcóatl e Tezcatlipoca, Códice Borbónico.

-

Deidade en forma de serpe emplumada, probablemente Kukulcán, lintel en Yaxchilán.

-

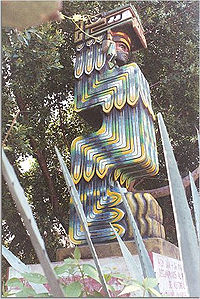

Estatua moderna de Quetzalcóatl, Amatlán de Quetzacóalt.

-

Quetzalcóatl en forma de serpe emplumada no Códice Telleriano-Remensis.

-

Quetzalcóatl no Códice Magliabechiano.

-

Quetzalcóatl no Códice Tovar.

-

Mural de Quetzalcóatl por Diego Rivera en Acapulco.

Notas

[editar | editar a fonte]- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 1,3 1,4 1,5 1,6 1,7 1,8 Cecilio A. Robelo (1905). Diccionario de Mitología Nahoa (en spanish). Editorial Porrúa. pp. 345–436. ISBN 970-07-3149-9.

- ↑ Jacques Soustelle (1997). Daily Life of the Aztecs. p. 1506.

- ↑ "Quetzalcoatl". Encyclopedia Britannica (en inglés). Consultado o 2021-03-29.

Véxase tamén

[editar | editar a fonte]| Wikimedia Commons ten máis contidos multimedia na categoría: Quetzalcóatl |

| A Galipedia ten un portal sobre: Pobos indíxenas de América |

Ligazóns externas

[editar | editar a fonte]- Lenda da creación do home e do millo (en náhuatl) e (en castelán)

Bibliografía

[editar | editar a fonte]- Boone, Elizabeth Hill (1989). Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 79 part 2. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-792-0. OCLC 20141678.

- Burkhart, Louise M. (1996). Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico. New cultural studies series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1576-1. OCLC 33983234.

- David, Carrasco (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-09490-8. OCLC 0226094871.

- David Carrasco. Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition. O'brien Pocket Series. University Press of Colorado, 2001.

- Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl (2019). History of the Chichimeca Nation: Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl's Seventeenth-Century Chronicle of Ancient Mexico. Edited and translated by Amber Brian, Bradley Benton, Peter B. Villella, & Pablo García Loaeza. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-6398-7.

- Florescano, Enrique (1999). The Myth of Quetzalcoatl. Traducido por Lysa Hochroth. Raúl Velázquez (illus.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7101-8. OCLC 39313429. Translation of El mito de Quetzalcóatl, original Spanish-language.

- Gardner, Brant (1986). "The Christianization of Quetzalcoatl". Sunstone 10 (11). Arquivado dende o orixinal o 18 de maio de 2022. Consultado o 08 de setembro de 2022.

- Gillespie, Susan D (1989). The Aztec Kings: The Construction of Rulership in Mexica History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1095-4. OCLC 60131674.

- Harvey, Doug (2012). "How a Feathered God Presided Over a Golden Age of Mexican Art". Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment of the Humanities 33 (5): 34–39.

- Hodges, Blair (29 de setembro de 2008). "Method and Skepticism (and Quetzalcoatl...)". Life on Gold Plates. Arquivado dende o orixinal o 9 de abril de 2012.

- James, Susan E (Winter 2000). "Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult". Journal of the Southwest (Tucson: University of Arizona Press) 42 (4): 897–926. ISSN 0894-8410. OCLC 15876763.

- Knight, Alan (2002). Mexico: From the Beginning to the Spanish Conquest. Mexico, vol. 1 of 3-volume series (pbk ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89195-7. OCLC 48249030.

- Lafaye, Jacques (1987). Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813. Traducido por Benjamin Keen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46788-0.

- Lawrence, D.H. (1925). The Plumed Serpent.

- Locke, Raymond Friday (2001). The Book of the Navajo. Hollaway House.

- Lockhart, James, ed. (1993). We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Repertorium Columbianum, vol. 1. James Lockhart (trans. and notes). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07875-6. OCLC 24703159. (en inglés)'(en castelán)'(en náhuatl)

- Martínez, Jose Luis (1980). "Gerónimo de Mendieta (1980)". Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl 14.

- Nicholson, H.B. (2001). Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: the once and future lord of the Toltecs. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-547-4.

- Nicholson, H.B. (2001). The "Return of Quetzalcoatl": did it play a role in the conquest of Mexico?. Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos.

- Phelan, John Leddy (1970) [1956]. The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520014046.

- Pohl, John M.D. (2003). "Creation Stories, Hero Cults, and Alliance Building: Postclassic Confederacies of Central and Southern Mexico from A.D. 1150–1458". En Michael Smith; Frances Berdan. The Postclassic Mesoamerican World. University of Utah Press. pp. 61–66.

- Pohl, John M.D. (2016). "Dramatic Performance and the Theater of the State: The Cults of the Divus Triumphator, Parthenope, and Quetzalcoatl". En John M.D. Pohl; Claire L. Lyons. Altera Roma: Art and Empire from Mérida to México. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. pp. 127–146.

- Pohl, John M.D.; Virginia M. Fields; Victoria L. Lyall (2012). "Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico: Introduction". Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico. Scala Publishers Ltd. pp. 15–49.

- Restall, Matthew (2003). Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516077-0. OCLC 51022823.

- Restall, Matthew (2003). "Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs (review)". Hispanic American Historical Review 83 (4). doi:10.1215/00182168-83-4-750.

- Ringle, William M.; Tomás Gallareta Negrón; George J. Bey (1998). "The Return of Quetzalcoatl". Ancient Mesoamerica (Cambridge University Press) 9 (2): 183–232. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001954.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23015-1. OCLC 48579073.

- Taylor, John (1892) [1882]. An Examination into and an Elucidation of the Great Principle of the Mediation and Atonement of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Deseret News. p. 201.

- Townsend, Camilla (2003). "No one said it was Quetzalcoatl: Listening to the Indians in the conquest of Mexico". History Compass 1 (1): **. doi:10.1111/1478-0542.034.

- Townsend, Camilla (2003). "Burying the White Gods: New perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico". The American Historical Review 108 (3). doi:10.1086/ahr/108.3.659.

- Wirth, Diane E (2002). "Quetzalcoatl, the Maya maize god and Jesus Christ". Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute) 11 (1): 4–15. Arquivado dende o orixinal o 17 de febreiro de 2009. Consultado o 08 de setembro de 2022.