User:Malikhpur/sandbox

The Lyallpur Young Historians Club , a lso known as LYHC, is an online club based in Faisalabad, Pakistan which brings together researchers and academics from Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab, India and the Punjabi d iaspora. LYHC provides an online platform which transcends international borders and provides a database for res earchers in the Pun jabi language which i s spoken in Pakistan, India and by the Punjabi diaspora. Recogn isi ng the importance of LYHC, the Unive rsity of British Columbia has listed LYHC in a list of online resources on modern Punjabi language and liter ature.[1] .. The aim of the club is to discuss the history of the Punjab. Originally, LYHC consisted of in-person meetings among st various intellectual, historians and social scientists from Pakistan. However, since 2020, LYHC has been organising online lectures on history a nd various topics with guests invited from around the world.[2][3] The lectures and discussions can be accessed online on Youtube.[4]

The lectures are primarily in Punjabi. Writing in the Times of India (17/08/2023), Syal states that:[5]

all these programmes — talks, interviews, discussions — are in the Punjabi language, the th read t hat binds Punjab spiritually and culturally.

References

[edit]- ^ University of British Columbia: Anne Murphy's list of resources [1]

- ^ Walia, R akesh (22.08.2020) Art historian Dr Anju Bala of GGSCW- delivers a special lecture for Lyallpur Young Historians Club (accessed 29.08.2020)

- ^ Tribune 23.08.2020 (accessed 29.08.2020)

- ^ https:/ /www.youtube.com/c/LyallpurYoungHistoriansClub

- ^ The Times of India (17/08/23) accessed on 21/08/23 Pushpinder Syal: How the Punjabi language is bringing people on both sides of the India-Pakistan border together Scar s of Partition remain, politics lets it down, but people won't. [ress.com/article/opinion/columns/punjabi-language-people-india-pakistan-border-8893928/]

Lyallpur Young Historians Club (LYHC)

The Lyallpur Young Historians Club, also known as LYHC, is an online club based in Faisalabad, Pakistan which brings together researchers and academics from Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab, India and the Punjabi diaspora. LYHC provides an online platform which transcends international borders and provides a database for researchers in the Punjabi language which is spoken in Pakistan, India and by the Punjabi diaspora. Recognising the importance of LYHC, the University of British Columbia has listed LYHC in a list of online resources on modern Punjabi language and literature.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

The aim of the club is to discuss the history of th e Punjab. Originally, LYHC consisted of in-person meetings amongst various intellectual, historians and social scientists from Pakistan. However, since 2020, LYHC has been organising online lectures on history and various topics with guests invited from around the world.[1][2]

The lectures and discussions can be accessed online on Youtube. The lectures are primarily in Punjabi. Writing in the Times of India, Syal states that : "all these programmes — talks, interviews, discussions — are in the Punjabi language, the thread that binds Punjab spiritually and culturally." [3]

.......

The census data for Punjabi is as follow: .

........

census 1881

Dogri (inc Chambeali) 108,019 (figures for Punjab only)...

Punjabi 14,233,95

source https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/report-on-the-census-of-british-india-taken-on-the-17th-of-february-1881-vols-i-iii/

Total standard Punjabi Dogri

1911 ...14,111,215 13,353,840 757,375 1901 15,272,322 15,250,162 22,160 sourec http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/ideologie/data/CensusIndia/CensusIndia1911/1911%20-%20Punjab%20-%20Vol%20I.pdf

Panjabi .. 13,218,474 1 911 Kahluri 94,697 Bilaspuri 141 Doabi 38,245 Malwai 2,113 Jangli 112 Jhangwali 22 Gurmukhi 15 Majhi 6 L&hori 5 Nal£garhi .. 5 Bhatiani 3 Gurd4spuri . 1 Jullunduri . 1

13,353,840

Dogri

Kangri ... 599,455

Dogri ... 157,531

Jammuali 299

Kandeali ... 76

Katochi ... 13

Bhatiali 1

757,375

Kangri in the 1901 census was treated as Western Pahari but in the 1911 Census as Punjabi or Dogri.

Lehndi 1911 Census Lehndi has been returned as follows: Derewal. Dhanni or Dhanauchi. Ghebi. Hindko or Hindki. Jatiali or Jatki, Jhelumwali. Kacbhi. Khetrani. Khushibi. Multani. Peshawari. Pindochi. Pothwari. Thalochari. Tinoli. Ubhechi. Western Panjabi 4,253,566

1901 census 2,829,000

1921 census Panjabi 12,833,008 Lehnda 3,689,838 http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/ideologie/data/CensusIndia/CensusIndia1921/CensusIndia1921IndiaTables.pdf

Nagar Kirtans | |||||

Celebration around the world | |||||||||||||||

Kurta styles | |||||||||||||||

English festivals (U.K)

A number of Christian and secular festivals are traditionally celebrated in England.

Plough Monday

[edit]Plough Monday is the traditional start of the English agricultural year. While local practices may vary, Plough Monday is generally the first Monday after Twelfth Day (Epiphany), 6 January.[4][5] References to Plough Monday date back to the late 15th century.[5] The day before Plough Monday is sometimes referred to as Plough Sunday.

The day traditionally saw the resumption of work after the Christmas period in some areas, particularly in northern England and East England.[6] The customs observed on Plough Monday varied by region, but a common feature to a lesser or greater extent was for a plough to be hauled from house to house in a procession, collecting money. They were often accompanied by musicians, an old woman or a boy dressed as an old woman, called the "Bessy," and a man in the role of the "fool." 'Plough Pudding' is a boiled suet pudding, containing meat and onions. It is from Norfolk and is eaten on Plough Monday.[4]

Plough Monday customs declined in the 19th century but were revived in some towns in the 20th.[7] They are now mainly associated with Molly dancing and a good example can be seen each year at Maldon in Essex.

Instead of pulling a decorated plough, during the 19th century, men or boys would dress in a layer of straw and were known as Straw Bears who begged door to door for money. The tradition is maintained annually in January, in Whittlesey, near Peterborough where on the preceding Saturday, "the Straw Bear is paraded through the streets of Whittlesey".[8]

May Day

[edit]

Traditional English May Day rites and celebrations include crowning a May Queen and celebrations involving a maypole. Historically, Morris dancing has been linked to May Day celebrations.[9] Much of this tradition derives from the pagan Anglo-Saxon customs held during "Þrimilci-mōnaþ"[10] (the Old English name for the month of May meaning Month of Three Milkings) along with many Celtic traditions.[11][12]

May Day has been a traditional day of festivities throughout the centuries, most associated with towns and villages celebrating springtime fertility (of the soil, livestock, and people) and revelry with village fetes and community gatherings. Seeding has been completed by this date and it was convenient to give farm labourers a day off. Perhaps the most significant of the traditions is the maypole, around which traditional dancers circle with ribbons. The spring bank holiday on the first Monday in May was created in 1978; May Day itself – May 1 – is not a public holiday in England (unless it falls on a Monday).

Halloween

[edit]

The term Halloween is derived from the phrase All Hallows Even which refers to the eve of the Christian festival of All Saint's held on 1 November. It begins the three-day observance of Allhallowtide,[13] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[14][15] Modern customs observed on Halloween have been influenced by American traditions and include trick or treating, wearing costumes and playing games.

In England, historically Halloween was associated with Souling which is a Christian practice carried out during Allhallowtide and Christmastide. The custom was popular in England and is still practised to a minor extent in Sheffield and Cheshire during Allhallowtide. The custom was also popular in Wales and has counterparts in the Philippines and Portugal that are practiced to this day.[16]

According to Morton (2013), Souling was once performed throughout the British Isles and the earliest activity was reported in 1511.[17] However, by the end of the 19th century, the extent of the practice during Allhallowtide was limited to parts of England and Wales.

According to Gregory (2010), Souling involved a group of people visiting local farms and cottages. The merrymakers would sing a "traditional request for apples, ale, and soul cakes.[18] The songs were traditionally known as Souler's songs and were sung in a lamentable tone during the 1800s.[19] Sometimes adult soulers would use a musical instrument, such as a Concertina.[20]

Rogers (2003) believes Souling was traditionally practised in the counties of Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, peak district of Derbyshire, Somerset and Herefordshire.[21] However, Souling also was associated with other areas. Hutton (2001) believes Souling took place in Hertfordshire.[22] Palmer (1976) states that Souling took place on All Saints day in Warwickshire.[23] However, the custom of Souling ceased to be followed relatively early in the county of Warwickshire but the dole instituted by John Collet in Solihull (now within West Midlands) in 1565 was still being distributed in 1826 on All Souls day.. The announcement for collection was made by ringing church bells.[24] Further, soul-cakes were still made in Warwickshire (and other parts of Yorkshire) even though no one visited for them.[25]

According to Brown (1992) Souling was performed in Birmingham and parts of the West Midlands;[26] and according to Raven (1965) the tradition was also kept in parts of the Black Country.[27] The prevalence of Souling was so localised in some parts of Staffordshire that it was observed in Penn but not in Bilston, both localities now in modern Wolverhampton.[28][29] In Staffordshire, the "custom of Souling was kept on All Saints' Eve" (halloween).[30]

Similarly in Shropshire, during the late 19th century, "there was set upon the board at All Hallows Eve a high heap of Soul-cakes" for visitors to take.[31] The songs sung by people in Oswestry (Shropshire) contained some Welsh.[32]

According to Harrowven (1979), Souling is "a fusion of pagan and Christian ritual".[33] The customs associated with Souling during Allhallowtide include or included consuming and/or distributing soul cakes, singing, carrying lanterns, dressing in disguise, bonfires, playing divination games, carrying a horse's head and performing plays. Souling is still practices in Cheshire and Sheffield.

Christmas

[edit]

Christmas is an annual commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ,[34][35] observed on December 25 A feast central to the Christian liturgical year, it is preceded by the season of Advent or the Nativity Fast and initiates the season of Christmastide, which historically in England lasts twelve days and culminates on Twelfth Night.[36]

Christmas decorations are put up in shops and town centres from early November. Many towns and cities have a public event involving a local or regional celebrity to mark the switching on of Christmas lights. Decorations in people's homes are commonly put up from early December, traditionally including a Christmas tree, cards, and lights both inside and outside the home. Every year, Norway donates a giant Christmas tree for the British to raise in Trafalgar Square as a thank you for helping during the Second World War. Christmas carolers at Trafalgar Square in London sing around the tree on various evenings up until Christmas Eve and Christmas decorations are traditionally left up until the evening of January 5 (the night before Epiphany); it is considered bad luck to have Christmas decorations up after this date. In practice, many Christmas traditions, such as the playing of Christmas music, largely stop after Christmas Day.[37]

Mince pies are traditionally sold during the festive season and are a popular food for Christmas.[38] Other traditions include hanging Advent calendars, holding the Nativity plays, giving presents and eating the traditional Christmas dinner.

.

Boxing Day is a bank holiday, and if it happens to fall on a weekend then a special Bank Holiday Monday will occur. Other traditions include carol singing, sending Christmas cards, going to Church and watching the Christmas pantomime for children.

Tipri dance (Punjab)

[edit]Tipri is a Punjabi stick dance popular in Patiala (Punjab, India) and Ambala (Haryana).

Style According to Randhawa (1960), Tipri is performed by boys and men using small sticks. The participants dance in a circle striking the sticks. The dancers also hold a rope which is tied at the top end to a pole. Each dancer then weaves the rope with the ropes of the other dancers. The ropes are then untangled whilst the dancers strike the sticks. Randhawa suggests that the dance is performed in Patiala city and is similar to dandiya of Bombay (Mumbai) and tipni of Rajasthan.[39]

Singh writing for the Tribune in 2000 states that "Tipri, a local version of dandia of Gujarat and a characteristic of the Patiala and Ambala districts, is losing popularity. Its performances are now limited to the occasions of Bavan Dvadsi, such as today." According to Singh (2000) "Bavan Dvadsi is a local festival "celebrated only in the Patiala and Ambala districts. Anywhere else, people are not aware of it. Now, tipri is performed during this festival only." Singh then states that Bavan Dvadsi "is to celebrate the victory of Lord Vishnu, who in the form of a dwarf, had tricked Raja Bali to grant him three wishes, before transforming into a giant to take the Earth, the sky and Bali’s life". Tripri competitions are held during the festival. Dancers dance in pairs, striking the sticks and creating a rhythm.[40]

Daura suruwal

[edit]In Nepal, the traditional male dress, which is also the national dress, is the Nepali shirt called daura[41] and suruwal (Nepali: दौरा सुरूवाल)[42] or daura-suruwal suit. The upper garment is the long Nepali shirt, which is similar to the Guajarati kediyu, but does not have the pleats going across the chest, but has cross-tied flaps.[43] The daura is a modification of the upper garments worn in Rajasthan.[44]

The Nepali suruwa/suruwal is a combination of the churidar[45][46] and the lower garment worn in the coastal regions of Gujarat, especially Saurashtra and Kutch where the garment is also called suruwal[47] (and chorno/kafni). It is tight along the legs but wide at the hips.[48] However, the suruwa fits comfortably around the legs so that it can be tapered tightly around the ankles.[49]

-

Daura suruwal, Nepal's national male dress.

-

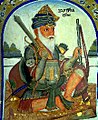

Prithvi Narayan Shah of Nepal in daura shalwar.

Vasiakhi

[edit]| Vaisakhi

Procession by Sikhs | |

|---|---|

| Also called | Vaisakh(few people also call this festival as baisakhi) |

| Observed by | Hindus and Sikhs |

| Type | religious, cultural |

| Significance | Hindu Solar New Year [50] Harvest festival, birth of the Khalsa, Punjabi new year |

| Celebrations | Fairs, Ritual Bathing, Amrit Sanchaar (baptism) for new Khalsa, Parades and Nagar Kirtan |

| Observances | Prayers, processions, raising of the Nishan Sahib flag, Fairs,dancing in the farms etc. |

| Related to | South and Southeast Asian solar New Year |

Punjabi folk religion: Difference between revisions

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Revision as of 11:11, 23 June 2021 (edit)

Malikhpur (talk | contribs)

(reinstate)

← Previous edit

Latest revision as of 13:11, 23 June 2021 (edit) (undo) (thank)

LearnIndology (talk | contribs)

(Describe why the page is needed instead of WP:STONEWALLING)

Tag: New redirect

Line 1: Line 1:

+

- REDIRECT Religion in Punjab

− Punjabi folk religion incorporates local mysticism [53] and refers to the beliefs and practices strictly indigenous to the Punjabi people, of the Punjab region including ancestral worship, worship of indigenous gods, and local saints. There are many shrines in Punjabi folk religion which represents the folk religion of the Punjab region which is a discourse between different organised religions.[54]

According to Singh and Gaur (2009), these shrines represent inter-communal dialogue and a distinct form of cultural practice of saint veneration.[55] Weekes (1984) discussing Islam states that:

- "Punjabi folk religion weaves a rich variety of local mysticism — such as beliefs in the evil eye , the predictions of astrologers and the potency of amulets and potions — into the scriptural , universalizing traditions of Islam propounded by the ulama."[56]

Punjabi folk cosmology

[edit]In Punjabi folk cosmology, the universe is divided into three realms:[57]

| English | Punjabi | Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|

| Sky | Akash | Dev Lok (Angels) |

| Earth | Dharti | Matlok (Humans) |

| Underworld | Nagas | Naglok (Serpents) |

Devlok is the realm of the gods, saints and ancestors, existing in akash, the sky. Ancestors can become gods or saints.[57]

Punjabi ancestral worship

[edit]Jathera—ancestral shrines

[edit]According to Bhatti and Michon (2004), a jathera is a shrine constructed to commemorate and show respect to the founding common ancestor of a surname and all subsequent common clan ancestors.[57]

Whenever a founder of a village dies, a shrine is raised to him on the outskirts of the village and a jandi tree is planted there. A village may have many such shrines.

The jathera can be named after the founder of the surname or the village. However, many villages have unnamed jathera. In some families, the founder of the jathera is also a saint. In such instances, the founder has a dual role of being the head of a jathera (who is venerated by his descendants) and also of being a saint (such as Baba Jogi Pir; who can be worshiped by any one).[57]

Punjabi people believe that members of a surname all hail from one common ancestor. A surname in Punjabi is called a gaut or gotra.[57]

Members of a surname are then subdivided into smaller clans comprising related members who can trace their family tree. Typically, a clan represents people related within at least seven generations but can be more.[58]

In ancient times, it was normal for a village to comprise members of one surname. When people moved to form a new village, they continued to pay homage to the founding jathera. This is still the case for many people who may have new jathera in their villages but still pay homage to the founding ancestor of the entire surname.[57]

Over time, Punjabi villages changed their composition whereby families from different surnames came to live together. A village therefore can have one jathera which can be communally used by members of different surnames but has the founder of the village as the named ancestor or many jathera can be built to represent the common ancestors of specific surnames.[59]

When members of a clan form a new village, they continue to visit the jathera in the ancestral village. If this is not possible, a link is brought from the old jathera to construct a new jathera in the new village.[57]

People visit the jathera when getting married, the 15th of the Indian month and sometimes on the first Sunday of an Indian month. The descendants of the elder go to a pond and dig earth and make shivlinga and some put it on the mound of their jathera and offer ghee and flowers to the Jathera.So, It is a form of shivlinga puja also. In some villages it is customary to offer flour.[57]

List of jathera

[edit]| Jathera | Surname |

|---|---|

| Pir Baba Kala Mehar | Sandhu Jat |

| Daadi Chiho Ji, Banga | Parmar |

| Baba Jogi Pir | Chahal Jat |

| Baba Kaallu Nath | Romana |

| Baba Sidh Kalinjhar | Bhullar Jat |

| Lakhan Pir | Cheema Jat |

| Talhan | Sehgal |

| Pir Baddon Ke | Cheema Jat |

| Sidhsan | Randhawa Jat |

| Tilkara | Sidhu Jat |

| Talwan | Jandu |

| Sidh Surat Ram | Gill Jat |

| Tulla | Bassi |

| Phalla | Dhillon clan Jat of Maharampur |

| Samrai | Kapila |

| Hakim Pur | Korpal |

| Adi | Garcha Jat |

| Jathera in village Takhni, Hoshiarpur | Guggi |

| Baba Mana Ji | Shergill Jat |

| Baba Kartar Singh Ji, Jamalpur ASR | Aulakh Jat |

| Baba Siria Ji (village Talwandi Khurd, Dist. Mullanpur Punjab) | Dubb |

| Baba Kuldhar Ji (village Ghudani Kalan, Dist. Ludhiana Punjab) | Kashyap Gotra Brahaman |

| Andloo, District Ludhiana, Punjab | Sootdhar |

Fairs

[edit]The following are some fairs celebrated in Punjab.

Baba Kaallu Nath Mela

[edit]A large Mela is organized at village Nathana (near Bhucho Mandi) in district Bathinda in the month of February–March in honor of Baba Kaallu Nath of the Romana surname. The Mela lasts for four days. The first day is especially for Romana's and three days for all people to attend.

Baba Kala Mehar Mela

[edit]A Mela is held in honor of Baba Kala Mehar every year in Amritsar district.

The fair takes place in and around April each year with Sandhu Jats and people from other clans and tribes attending from around Punjab and Rajasthan.

According to legend, Baba Kala Mehar used to tend to his cattle and one day while doing so, he happened to meet Baba Gorakh Nath (Gorakshanath). Baba Gorakh Nath asked Pir Baba Kala Mehar if he can give him some milk from his buffaloes. A miracle happened that while the cattle being tended at that time were all bulls, Baba Ji is said to have miraculously taken milk out of bulls on striking them with his stick.

Baba Jogi Pir Mela

[edit]The village of Bhopal falls in the Mansa tehsil of Bathinda district.

The village is known for the fair of Baba Jogi Pir[60] who is said to be the guru (preceptor) of Chahal Jat. It is said that during the times of Mughal rule, Baba Jogi Pir fought against the forces of the Mughal rulers.

During the battle, his head was chopped off, but his headless body kept on fighting until it fell down dead in this village. The people were deeply touched by the sacrifice of Jogi Pir, constructed a shrine, and began to hold a fair.[60]

Another legend narrates that once a few people stayed under a grove of trees in the premises of the shrine. They felt pangs of thirst at night, but there was no source of water where from they could quench their thirst . A heavenly voice which was believed to be that of Jogi Pir was heard: “why do you die of thirst? Pick out a brick from the pond and take water”. They did likewise, found water from underneath the brick they picked up and thus they quenched their thirst.[60]

A fair is held twice annually for three days on Bhadon 28 (August–September)and Chet 16 (March- April) at the shine of Jogi Pir. It is attended by both Hindus and Sikhs. The people pay their obeisance at the shrine, especially after the birth of a child or the solemnization of marriage. Earth is also scooped one of the tank by the people for invoking the blessings of Jogi Pir.[60]

Shrines

[edit]Shrines in honour of saints are common in the Punjab region. A Shaheed Shrine is a building constructed to commemorate and show respect to a saint.[61] Muslim shrines are referred to a dargahs and Hindu shrines are known as samadhs.

Various saints are venerated in Punjab such as Khawaja Khidr is a river spirit of wells and streams.[62] He is mentioned in the Sikandar-nama as the saint who presides over the well of immortality, and is revered by many faiths.[62] He is sometimes pictured as an old man dressed in green, and is believed to ride upon a fish.[62] His principal shrine is on an island of the Indus River by Bhakkar in Punjab, Pakistan.[62] Gugga Pir is venerated for protection against snakes. The fair known as Chhapar Mela is organised annually.

Many villages in Punjab, India and Pakistan, have shrines of Sakhi Sarwar who is more popularly referred to as Lakha Data Pir. A shrine of Sakhi Sarwar is situated in district Dera Ghazi Khan in Punjab, of Pakistan, where an annual fair is held in March. A 9-day fair is organised every year in Mukandpur, Punjab, India.

Other shrines are in honour of Seetla Mata who is worshiped for protection against childhood diseases with notable fair being held annually in Ludhiana district and is known as the Jarag mela;[63] Gorakhnath who was an 11th to 12th century[64]Nath yogi and connected to Shaivism; and Puran Bhagat who is a revered saint in the Punjab region and other areas of the subcontinent.[65] People visit Puran's well located in Sialkot, especially childless women travel from places as far as Quetta[66] and Karachi.

Gallery

[edit]-

Baba Bulleh Shah Tomb, Kasur, Pakistan

-

Shrine of Bhagat Baba Kalu Ji Panchhat

-

Gurudwara Sahib & Baba Bala ji Smadh Ghuriana

-

Tapa Singh Shaheed

-

Tomb of Ahmad Sirhindi, Rauza Sharif Complex, Sirhind

-

Ustad's Tomb Nakodar, Punjab

-

Tombs of Ustad in Nakodar

-

08IN2130 prayer flags Hindu shrine and red flag

-

19th century Indian shrine 01

-

Guru Bhag Singh Kartarpur Punjab India (Vadbhag)

-

Swami Sarvanand Giri

-

Bhagat Baba Kalu Ji Panchhat

-

Indian goddess Sitala seated on a donkey Wellcome V0050537

-

Shrine Baba Budda Ji Nakodar

-

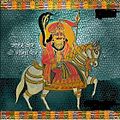

Khidr

-

VeerGogaji

References

[edit]- ^ Walia, Rakesh (22.08.2020) Art historian Dr Anju Bala of GGSCW- delivers a special lecture for Lyallpur Young Historians Club (accessed 29.08.2020)

- ^ Tribune 23.08.2020 (accessed 29.08.2020)

- ^ The Times of India (17/08/23) accessed on 21/08/23 Pushpinder Syal: How the Punjabi language is bringing people on both sides of the India-Pakistan border together Scars of Partition remain, politics lets it down, but people won't. [ss.com/article/opinion/columns/punjabi-language-people-india-pakistan-border-8893928/]

- ^ a b Hone, William (1826). The Every-Day Book. London: Hunt and Clarke. p. 71.

- ^ a b "Plough Monday". Oxford English Dictionary (online edition, subscription required). Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ^ Millington, Peter (1979). "Plough Monday Customs in England". Folk Play Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland. Master Mummers. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "The English Tradition of Plough Monday". churchmousec.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- ^ Project Britain[2]

- ^ Rodney P. Carlisle (2009) Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society, Volume 1. SAGE [3]

- ^ Caput XV: De mensibus Anglorum from De mensibus Anglorum. Available online: [4]

- ^ Blumberg, Antonia (2015-04-30). "Beltane 2015: Facts, History And Traditions Of The May Day Festival". HuffPost. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ^ "Beltane". BBC. June 7, 2006. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ "Tudor Hallowtide". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

Hallowtide covers the three days – 31 October (All-Hallows Eve or Hallowe'en), 1 November (All Saints) and 2 November (All Souls).

- ^ Hughes, Rebekkah (29 October 2014). "Happy Hallowe'en Surrey!" (PDF). The Stag. University of Surrey. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Halloween or Hallowe'en, is the yearly celebration on October 31st that signifies the first day of Allhallowtide, being the time to remember the dead, including martyrs, saints and all faithful departed Christians.

- ^ Don't Know Much About Mythology: Everything You Need to Know About the Greatest Stories in Human History but Never Learned (Davis), HarperCollins, p. 231

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Fieldhouse2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morton, Lisa (2013) Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween.Reaktion Books [5]

- ^ Gregory, David (2010) The Late Victorian Folksong Revival: The Persistence of English Melody, 1878-1903 Scarecrow Press [6]

- ^ Fleische (1826) An Appendix to His Dramatic Works. Contents: the Life of the Author by Aus. Skottowe, His Miscellaneous Poems; a Critical Glossary, Comp. After Mares, Drake, Ayscough, Hazlitt, Douce and Others[7]

- ^ Morton, Lisa (2013) Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween.Reaktion Books [8]

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas (2003) Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press. [9]

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2001) Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. OUP Oxford [10]

- ^ Palmer, Roy (1976) The folklore of Warwickshire, Volume 1976, Part 2 Batsford [11]

- ^ v (2007) Dugdale Society [12]

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2001) Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. OUP Oxford [13]

- ^ Brown, Richard (1992)The Folklore, Superstitions and Legends of Birmingham and the West Midlands. Westwood Press Publications [14]

- ^ Raven, Michael (1965)Folklore and Songs of the Black Country, Volume 1. Wolverhampton Folk Song Club[15]

- ^ Folklore, Volume 25 (1969)[16]

- ^ Publications, Volume 106. W. Glaisher, Limited, 1940.[17] The tradition was noted in 1892 to be held in Penn which is now in Wolverhampton, West Midlands.

- ^ Publications, Volume 106. W. Glaisher, Limited, 1940.[18]

- ^ Walsh, William Shepard (1898) Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities. Gale Research Company [19]

- ^ The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Volume 62 (1886) J. W. Parker and Son [20]

- ^ Harrowven, Jean, (1979) The Origins of Rhymes, Songs and Sayings. Kaye & Ward [21]

- ^ Christmas, Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

Archived 2009-10-31. - ^ Martindale, Cyril Charles."Christmas". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (October 1, 2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide.

On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.

After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on December 25 and January 6, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians slowly adopted a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas. - ^ "British Christmas: introduction, food, customs". Woodlands-Junior.Kent.sch.uk. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Christmas dinner". Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Mohinder Singh Randhawa. (1960) Punjab: Itihas, Kala, Sahit, te Sabiachar aad.Bhasha Vibhag, Punjab, Patiala.

- ^ Singh, Jangveer (10.09.2000) The Tribune: Tipri rhythms are fading out in region accessed 04.10.2019) [22]

- ^ Bindloss, Joseph (15 September 2010). Nepal 8. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781742203614 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nepali, Gopal Singh (1965). The Newars: an ethni-sociological study of a Himalayan community. [23]

- ^ Croos, J.P (1996). The Call of Nepal: a personal Nepalese odyssey in a different dimension. [24]

- ^ Tulasī Rāma Vaidya, Triratna Mānandhara, Shankar Lal Joshi (1993) Social history of Nepal [25]

- ^ "The Muslim World League Journal". Press and Publications Department, Muslim World League. 1 March 2003 – via Google Books.

- ^ Acharya, Madhu Raman (2002) Nepal culture shift!: reinventing culture in the Himalayan kingdom [26]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

autogenerated5was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ West Bengal District Gazetteers: Darjiling, by Amiya Kumar Banerji ... [et al (1980) [27]

- ^ Tetley, Brian (1 January 1991). The insider's guide to Nepal. Gregory's. ISBN 9780731903825 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ColeSambhi1995p63was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "April 2020 Official Central Government Holiday Calendar". Government of India. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "April 2021 Official Central Government Holiday Calendar". Government of India. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Nagendra Kr Singh, Abdul Mabud Khan (2001) Encyclopaedia of the World Muslims: Tribes, Castes and Communities, Volume 3. Global vision[28]

- ^ Replicating Memory, Creating Images: Pirs and Dargahs in Popular Art and Media of Contemporary East Punjab Yogesh Snehi "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Historicity, Orality and ‘Lesser Shrines’: Popular Culture and Change at the Dargah of Panj Pirs at Abohar,” in Sufism in Punjab:: Mystics, Literature and Shrines, ed. Surinder Singh and Ishwar Dayal Gaur (New Delhi: Aakar, 2009), 402-429

- ^ Weekes, Richard (1984) Muslim Peoples: Maba. Greenwood Press [29]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Centre for Sikh Studies, University of California. Journal of Punjab Studies Fall 2004 Vol 11, No.2 H.S.Bhatti and D.M. Michon: Folk Practice in Punjab". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ^ This is not definitive

- ^ A Glossary of the tribes & castes of Punjab by H. A Rose

- ^ a b c d Gazetteer of Bathinda 1992 Edition

- ^ Sandip Singh Chohan, Thesis for the University of Wolverhampton: The Phenomenon of possession and exorcism in North India and amongst the Punjabi Diaspora in Wolverhampton [30]

- ^ a b c d Longworth Dames, M. "Khwadja Khidr". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Jarag Mela of Punjab - Worshipping of Goddess Seetala".

- ^ Briggs (1938), p. 249

- ^ Ram, Laddhu. Kissa Puran Bhagat. Lahore: Munshi Chiragdeen.

- ^ Dawn 8 October 2012