Shoshenq III

| Shoshenq III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

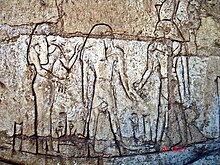

Shoshenq III, standing on the boat "msktt", the boat of the night, with the god Atum. From his tomb in Tanis. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | c. 841–c. 803/799 BC (or c. 831–c. 791/788 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Osorkon II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Shoshenq IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Tentamenopet Tadibaste Djededbastesankh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Ankhnes-Shoshenq Bakennefy A Pashedbaste B Takelot C Padebehenebaste Shoshenq IV? Pami I? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | c. 803/799 BC (or c. 791/788 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | NRT V, Tanis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 22nd Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The modern designation Shoshenq III refers to King Usermaatre Setepenre Shoshenq Sibaste Meryamun Netjerheqaon,[4] who reigned for about four decades, c. 841–c. 803/799 BC [5] or c. 831–c. 791/788 BC.[6] His highest attested regnal year is Year 39.[7] Although he apparently retained control of Tanis and, for the most part, of Bubastis and Memphis, for most of his long reign, Shoshenq III had to reckon with rival kings in parts of the country.[8]

Recent scholarship has corrected a number of earlier assumptions about the reign of Shoshenq III Sibaste. He was long thought to be the successor of Takelot II Siese and predecessor of Pami I Sibaste, and to have reigned for 52 years on the basis of the burial of a 26-year-old Apis Bull, installed in Year 28 of Shoshenq III, in Year 2 of Pami I.[9] It is now recognized that an additional king, designated Shoshenq IV, Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq Sibaste Meryamun Netjerheqaon, reigned between Shoshenq III and Pami for at least a decade, and that Shoshenq III and Shoshenq IV reigned for 52 years altogether.[10] Further, most Egyptologists now agree that Takelot II Siese did not intervene as king between Osorkon II Sibaste and Shoshenq III, but reigned as a rival or regional king, apparently somewhere in Upper Egypt, from the last years of Osorkon II Sibaste until Year 22 of Shoshenq III; therefore, Shoshenq III Sibaste was the direct successor of Osorkon II Sibaste.[11]

Origins

[edit]The family origins of Shoshenq III Sibaste are nowhere explicitly specified. The reappraisal of the chronological relationship between his reign and those of Osorkon II Sibaste and Takelot II Siese has invalidated the conjectural basis for considering Shoshenq III an apparent son of Takelot II, who succeeded him by allegedly displacing his brother, Takelot's rightful heir, the High Priest of Amun Osorkon.[12] Since Osorkon II Sibaste already had a son named Shoshenq "D", the High Priest of Ptah at Memphis, who was buried or reburied by Shoshenq III Sibaste,[13] it has been suggested that Shoshenq III Sibaste was a son of this Shoshenq "D" and a grandson of Osorkon II Sibaste.[14] Alternatively, it has also been suggested that Shoshenq III Sibaste was a younger homonymous brother of the High Priest of Ptah Shoshenq "D", and a late-born son of Osorkon II Sibaste.[15]

Reign

[edit]Shoshenq III Sibaste succeeded his probable grandfather Osorkon II Sibaste in what was already Year 4 of Takelot II Siese, another probable grandson of Osorkon II Sibaste.[16] It was Shoshenq III Sibaste that arranged for the burial of Osorkon II Sibaste in his tomb at Tanis (NRT I), where he is depicted making offerings to the gods.[17] Additionally, Shoshenq III seems to have signalled his succession to Osorkon II by adopting the same basic Praenomen (Usermaatre) and epithet (Sibaste, "son of Bastet"), in contrast to Takelot II's Praenomen (Hedjkheperre) and epithet (Siese, "son of Isis").[18]

Shoshenq III Sibaste appears to have retained control of his capital Tanis throughout his reign, together with most of Lower Egypt. His probably indirect authority over Thebes and Upper Egypt, however, was intermittent, as he faced one or two rival kings at most times. By his Year 6, the distant authority of Shoshenq III Sibaste was recognized at Thebes, with the High Priest of Amun Harsiese "B" dating to his reign, having temporarily displaced Takelot II Siese's son Osorkon.[19] From his Year 8, Shoshenq III Sibaste had to reckon with one more king, Padubaste I Sibaste/Siese, who became the new patron of the High Priest of Amun Harsiese "B".[20] Padubaste I has been considered a possible brother of Shoshenq III Sibaste [21] or perhaps a son of Osorkon II Sibaste's former rival, King Harsiese.[22] Because the High Priest of Amun Harsiese "B" dated to Year 5 of Padubaste I and Year 12 of (unnamed) Shoshenq III, on at least one occasion, it has been suggested that the two kings might have been allies at that time, in joint opposition to Takelot II Siese and his son Osorkon. Shoshenq III's son, the General Pashedbast, restored the foregate of Pylon X at Karnak, dating by the regnal count of Padubaste I, although the year is lost.[23] Whether as partner or rival of Shoshenq III Sibaste, Padubaste I is attested by his subjects' dedications at Memphis, and a donation stele at Bubastis. Takelot II Siese died in his Year 25, which corresponded to Year 22 of Shoshenq III Sibaste, and the high priest Osorkon now recognized Shoshenq's authority and dated by his reign at Thebes, in Years 22–25 and Years 26–29, briefly interrupted by Padubaste I and the High Priest of Amun Harsiese "B".[24] The last attestations of Shoshenq III Siese, also at Thebes and also in association with the High Priest of Amun Osorkon, is from Year 39.[25] Shortly thereafter, Shoshenq III died and the high priest Osorkon declared himself king, Osorkon III Siese.[26] Shoshenq III seems to have outlived all of his Upper Egyptian rivals, Takelot III Siese (last attested in Shoshenq III's Year 25) and the latter's apparent successor Iuput I (last attested in Shoshenq III's Year 33), and Padubaste I (last attested in Shoshenq III's Year 30) and the latter's apparent successor, the counterfactually-designated Shoshenq VI (actually Shoshenq IV, last attested in Shoshenq III's Year 36?).[27]

Shoshenq III Sibaste ruled throughout Lower Egypt, and in his Year 26 also at Heracleopolis, whose military commander Bakenptah is recorded as a brother of the High Priest of Amun Osorkon.[28] Although the Libyan chieftains continued to defer to the king's authority, it appears that in this period they began to surpass their original function as garrison commanders by becoming more involved in and controlling larger territories. Their greater role is documented by an increased number of donation stelae.[29] Some of the beneficiaries of this regionalisation were king's sons, or "king's sons of Rameses," like the king's eldest son Bakennefy "A" at Athribis, the general Takelot at Busiris, Padebehenbaste at Kom el-Hisn, and the Great Chief of Ma and High Priest of Ptah at Memphis, Takelot "B", a grandson of Osorkon II Sibaste and probably brother of the reigning king.[30] Other chiefs of Ma are attested at Mendes (Harnakhte) and Pharbaithos (Iufera).[31] The increasing autonomy of the chieftains was more pronounced among the more recently arrived Libu (rbw) than among the more integrated Ma (mʿ)/Meshwesh (mšwš).[32] The Libu might have been settled in the western Delta during the reign of Shoshenq III Sibaste, and they seem to have been united under the authority of a single chieftain, Inamunnifnebu, by Year 31.[33]

The name of Shoshenq III Sibaste appears throughout Lower Egypt, often in relation to building projects, for example at Tell Umm Harb, Bendariyah, Tell Balamun, and Kom el-Hisn. The main focus of his activity was the capital Tanis, where he opened a new monaumental gateway in the brick wall of the enclosure of the Temple of Amun, and where he also built his tomb (NRT V), using a simple design. The works at Tanis relied heavily on recycled building materials from Pi-Ramesses.[34] At Memphis, where the king built a chapel to the goddess Sekhmet,[35] Apis Bulls were buried in perhaps Year 4 and in Year 28, and a stele commemorating the latter was set up by king's probable nephew, the Great Chief of Ma Pediese, son of Takelot "B", and Pediese's sons the High Priest of Ptah Peftjauawybaste and the Sem Priest of Ptah Takelot.[36] In his Year 30, Shoshenq III Sibaste may have celebrated his Heb Sed Jubilee, but there seems to be no surviving commemoration of this event in the reliefs and inscriptions.[37]

After a reign of 39–42 years (latest attested date is Year 39), Shoshenq III Sibaste died and was buried in his tomb (NRT V) at Tanis. He was succeeded by his probable son, Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq Sibaste Netjerheqaon, counterfactually designated Shoshenq IV, although he reigned later than the Upper Egyptian king Usermaatre Meryamun Shoshenq Meryamun, counterfactually designated Shoshenq VI.[38] Shoshenq IV Sibaste reigned for 10–13 years (latest attested date is Year 10), and was succeeded by Usermaatre Setepenre Pami Sibaste Meryamun, designated Pami I. The latter could have been a son of either Shoshenq III or Shoshenq IV, with some scholars considering the relatively short reign of Shoshenq IV to suggest that he was followed by his brother rather than son.[39] Given the length of the reign of Shoshenq III, this does not appear very conclusive.

Family

[edit]Shoshenq III Sibaste had at least three known spouses and several known children:

The Great King's Wife Tentamenopet (tȝ-nt-jmn-jpt) [40]

- The King's Daughter Ankhnes-Shoshenq (ʿnḫ.n-s-ššnq), who married Iufa i [41]

The King's Wife Tadibaste (tȝ-dj-bȝstt), daughter of Tadibaste [45]

- The King's Eldest Son Bakennefy "A" (bȝk-n-nfy), prince of Athribis [46]

The King's Wife Djedbastesankh (ḏd-bȝstt-jw-s-ʿnḫ) [47]

- The King's Son or Rameses Takelot "C" (tkrjt), Commander of All Troops [48]

Unspecified Wives

- King's Son Pashedbaste "B" (pȝ-šd-bȝstt), General [49]

- ? King's Son of Rameses Padebehenbaste (pȝ-dbḥ.n-bȝstt), High Priest of Amun (at Kom el-Hisn?) [50]

- ? King Shoshenq IV Sibaste [51]

- ? King Pami I Sibaste (or son of Shoshenq IV Sibaste?) [52]

Probably not a son of Shoshenq III Sibaste, but rather a son of Shoshenq V Sibaste:

- The Chief of Ma Pami (pȝ-mjw, wrongly read as pȝ-mȝj, "Pimay"), son of the Lord of the Two Lands Shoshenq Meryamun, probably prince of Heracleopolis [53], previously thought to have been a prince of Sais, a son of Shoshenq III and possibly identical to the future King Pami I.[54]

-

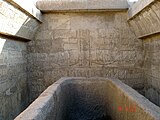

Tomb of Shoshenq III at Tanis.

-

Reliefs on the south wall of Shoshenq III's tomb.

-

Reliefs on the walls of the tomb.

References

[edit]- ^ Leprohon 2013: 149.

- ^ Leprohon 2013: 149-150.

- ^ Leprohon 2013: 150.

- ^ Leprohon 2013: 149-150.

- ^ Krauss 2006: 408-411; Aston 2009: 22-25; Krauss 2015: 338-340; Mladjov 2017: 15, n. 95; this dating prioritizes the astrochronological matches for the reign of Shoshenq III's contemporary Takelot II.

- ^ Aston 2009: 25-28; Dodson 2012: 198; Payraudeau 2020: 34-35; this dating prioritizes reducing the period of time between Takelot III and the Kushite king Piye.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 244.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 113-128; Payraudeau 2020: 130-142.

- ^ Gardiner 1961: 334; Kitchen 1996: 100-103, 348.

- ^ Rohl 1990; Dodson 1993; Kitchen 1996: xxv-xxvi; Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 244-245; Dodson 2012: 127-128; Payraudeau 2020: 142-143.

- ^ Aston 1989; Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 242-243, 250-251; Aston 2009: 1-3; Dodson 2012: 117, 198; Payraudeau 2014: 71; Payraudeau 2020: 136.

- ^ The interpretation of Kitchen 1996: 332-333.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 240 assumes that the high priest Shoshenq outlived his father Osorkon II Sibaste, but others suggest he might have died shortly before the king, e.g., Dodson 2012: 115.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 115, 228-229; Payraudeau 2014: 72; Lenzo et al. 2023: 172.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014: 72, 123, 126; Payraudeau 2020: 562; Lenzo et al. 2023: 172.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251; Payraudeau 2014: 63-66, 70-71; Payraudeau 2020: 127, 562.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014: 71.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014: 72.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251; Payraudeau 2014: 72; Payraudeau 2020: 131.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 476.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 107-108; Payraudeau 2014: 76; Payraudeau 2020: 132, 562.

- ^ Payraudeau 2020: 134.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251; Payraudeau 2014: 72; Payraudeau 2020: 132-133.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251; Payraudeau 2014: 73.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 251; Payraudeau 2014: 73-74, 81-83.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 2006: 249-252; Payraudeau 2014: 70, 80; Payraudeau 2020: 562.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 117; Payraudeau 2014: 73; Payraudeau 2020: 138.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014: 96-97; Payraudeau 2020: 138.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Payraudeau 2020: 140-141.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 345; Payraudeau 2020: 141.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014: 96-97; Payraudeau 2020: 140-141.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 345-347;Payraudeau 2020: 141.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 343; Dodson 2012: 115, 127-128.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 343.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 115-116.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 343.

- ^ Aston 2009: 3, n. 24.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 228; Payraudeau 2020: 142-144, 562.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 343; Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 343; Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 228.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 228.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 228.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125; Christian Settipani suggested identifying her as a daughter of the High Priest of Ptah Takelot "B": Nos ancêtres de l'Antiquité, 1991. Christian Settipani, p. 153, 163, 164 and 166.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125; Payraudeau 2020: 562.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Dodson 2012: 115, 122, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125; Payraudeau 2020: 134.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Dodson 2012: 115, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 125.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 228; Payraudeau 2014: 126; Payraudeau 2020: 562.

- ^ Dodson 2012: 134, 228; Payraudeau 2014: 126; Payraudeau 2020: 562.

- ^ Meffre 2015: 185-190, 343-347; Payraudeau 2020: 143-144, n. 7.

- ^ Kitchen 1996: 344; Dodson 2012: 115, 134, 228.

- Aston, David A., 1989: "Takeloth II: A King of the Theban 23rd Dynasty?," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 75: 139-153.

- Aston, David A., 2009: "Takeloth II, A King of the Herakleopolitan/Theban Twenty-Third Dynasty Revisited: The Chronology of Dynasties 22 and 23," in Broekman, G. P. F., R. J. Demarée, and O. E. Kaper, eds., The Libyan Period in Egypt, Leuven, 1-28.

- Dodson, Aidan, 1993: "A new King Shoshenq confirmed?," Göttinger Miszellen 137: 53-58.

- Dodson, Aidan, 2012: Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance, Cairo & New York.

- Gardiner, Sir Alan, 1961: Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford.

- Jansen-Winkeln, Karl, 2006: "The Chronology of the Third Intermediate Period," in Hornung, Erik, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton, eds., Ancient Egyptian Chronology, Leiden & Boston, 234-264.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A., 1996: The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), reprinted with a new preface and the 1986 supplement, Warminster.

- Krauss, Rolf, 2006: "Lunar Dates," in Hornung, Erik, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton, eds., Ancient Egyptian Chronology, Leiden & Boston, 395-431.

- Krauss, Rolf, 2015: "Egyptian Chronology: Ramesses II through Shoshenq III, with analysis of the lunar dates of Thutmoses III," Ägypten und Levante 25: 335-382.

- Lenzo, Giuseppina, Raphaëlle Meffre, Frédéric Payraudeau, La tombe memphite du prince héritier Chéchonq et son mobilier funéraire, Cairo, 2023.

- Leprohon, Ronald J., 2013: The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary, Atlanta.

- Meffre, Raphaëlle, 2015: D'Héracléopolis à Hermopolis: La Moyenne Égypte durant la Troisième Période intermédiate (XXIe–XXIVe dynasties), Paris.

- Mladjov, Ian, 2017: "The Transition between the Twentieth and Twenty-First Dynasties Revisited," Birmingham Egyptology Journal 5: 1-23.

- Payraudeau, Frédéric, 2014: Administration, société et pouvoir à Thèbes sous la XXIIe dynastie bubastide, 2 vols, Cairo.

- Payraudeau, Frédéric, 2020: L'Égypte et la vallée du Nil. Tome 3. Les époques tardives (1069–332 av. J.-C.), Paris.

- Rohl, David, 1990: "The Third Intermediate Period: Some Chronological Considerations," Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 3: 66-67.