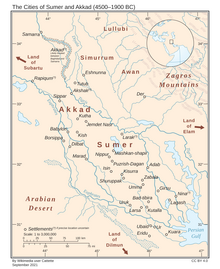

A map detailing the locations of various archaeological sites occupied by the archaeological culture of EDIIIb. | |

| Geographical range | Near East |

|---|---|

| Period | Early Dynastic |

| Dates | c. 2500/2450 – c. 2350/2334 BCE |

| Major sites | |

| Preceded by | Early Dynastic IIIa |

| Followed by | Akkadian Period |

| Defined by | Henri Frankfort |

The Early Dynastic IIIb period (abbreviated EDIIIb period or EDIIIb) is the fourth out of four sub-periods to an archaeological culture of Mesopotamia collectively referred to as the Early Dynastic (ED). Depending on which chronology for the Ancient Near East (ANE) is preferred among the present-day general consensus of mainstream historians, the Early Dynastic IIIb is usually said to have succeeded Early Dynastic IIIa c. 2500/2450 BCE by the Middle Chronology (MC), or c. 2375 BCE by the Short Chronology (SC); then, gradually transitioning into the Akkadian Period c. 2350/2334 BCE (MC), or even up to c. 2270/2230 BCE (SC).

EDIIIb saw an expansion in the use of writing and increasing social inequality. Larger political entities developed in Lower and Upper Mesopotamia; as well as, Southern and Western Iran. The Royal Cemetery at Ur dates back to EDIIIb. The EDIIIb is especially well-known through the Ebla tablets and Barton Cylinder.

The end of EDIIIb is not defined archaeologically but politically. The conquests of Sargon of Akkad and his successors upset the political equilibrium throughout Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The transition is much harder to pinpoint within an archaeological context. It is virtually impossible to date a particular site as being that of either EDIIIb or Akkadian using ceramic or architectural evidence alone.

Population

editTertius Chandler calculated a range of anywhere from 75 to 200 people inhabiting 1 hectare (110,000 square feet) for the population density of early settlements. Fekri Hassan used a population density standard of 100 inhabitants per hectare. Robert McCormick Adams Jr. estimated an average of 100, 125, or 200 inhabitants/hectare. Colin Renfrew also estimated 200 inhabitants/ha. Hans Jörg Nissen concurred with the density standard of 100—200 inhabitants/ha.

Colin McEvedy wrote that a population density of about 250 inhabitants/ha is a reasonable assumption. Yigael Yadin suggested a high estimate of nearly 600 inhabitants/ha. Paul Bairoch reports that many scholars have used population densities of up to 400 or even 700 per hectare.

Giovanni Pettinato estimated that Ebla occupied 56 hectares.

Henri Frankfort estimated that Mesopotamian city-states of the ED were inhabited by anywhere from 10,000—20,000 people. He offered population estimates for the following: Lagash (19,000 inhabitants); Umma (16,000); Eshnunna (9,000), and Tutub (12,000). Robert John Braidwood estimated the population of Sumer (c. 2500 BCE) at 500,000. Ruth Whitehouse estimated that there were probably never more than twenty city-states and named thirteen that would have had populations of anywhere from 10,000—20,000: Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, Shuruppak, Ur, Lagash, Larsa, Umma, Adab, Nippur, Akshak, and Kish.

Estimated settlement sizes (in hectares)

edit| Settlement | Nissen | Pettinato | Mallowan | Adams | Roux |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu | 50—500 | ||||

| Bad-tibira | 25 | 50—500 | |||

| Larak | 50—500 | ||||

| Sippar | 50—500 | ||||

| Shuruppak | 100 | ||||

| Kish | 84+ | 50—500 | |||

| Uruk | 250 | 400 | 50—500 | ||

| Ur | 50 | 50—500 | |||

| Nippur | 50 | 50—500 | |||

| Girsu | 50—500 | ||||

| Lagash | 50—500 | ||||

| Umma | 400 | 50—500 | |||

| Kesh | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Adab | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Isin | 50—500 | ||||

| Larsa | 50—500 | ||||

| Zabala | 40—200 | 50—500 | |||

| Akshak | 50—500 | ||||

| Shekhna | 100 | ||||

| Nagar | 75—100 | ||||

| Ebla | 56 | ||||

| Anshan |

Estimated settlement populations

edit| Settlement | Pettinato | Chandler | Whitehouse | Frankfort | McEvedy | Thompson | Modelski |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu | 10,000—20,000 | ||||||

| Bad-tibira | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Larak | 10,000—20,000 | ||||||

| Sippar | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Shuruppak | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—30,000 | 17,000 | ||||

| Kish | 10,000—20,000 | 20,000 | 25,000 | ||||

| Uruk | 50,000 | 50,000 | 30,000—40,000 | 50,000 | |||

| Ur | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 10,000 | ||||

| Adab | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | 13,000 | ||||

| Akshak | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000—20,000 | |||||

| Isin | |||||||

| Larsa | 10,000—20,000 | 10,000 | |||||

| Girsu | 40,000—80,000 | ||||||

| Lagash | 10,000—20,000 | 19,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 30,000—60,000 | 40,000 | ||

| Umma | 10,000—20,000 | 16,000 | 10,000—15,000 | 40,000 | 34,000 | ||

| Eshnunna | 9,000 | ||||||

| Tutub | 12,000 | ||||||

| Nippur | 10,000—20,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | ||||

| Kesh | 10,000 | 11,000 | |||||

| Zabala | 10,000 | ||||||

| Assur | |||||||

| Nineveh | |||||||

| Akkad | |||||||

| Mari | 40,000 | ||||||

| Ebla | ≤40,000 | 30,000 | |||||

| Shekhna | 20,000 | ||||||

| Nagar | 10,000—15,000 | 15,000 | |||||

| Tell Chuera | |||||||

| Anshan | 10,000 | ||||||

| Susa | 10,000—15,000 |

Ethnicities and languages

editEthnic groups

editLanguages

edit- Language isolates

- Proto-Euphratean

- Sumerian

- Emegir variety

- Emesal sociolect

- Elamite

- Semitic

Sumerian people

editMost historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled c. 5500 – c. 3300 BC by a West Asian people who spoke Sumerian (a non-Semitic, non-Indo-European, agglutinative, language isolate). Sumerian civilization originated in the southeastern reaches of the Fertile Crescent—a region once widely regarded by the general consensus of mainstream historians to be the only cradle in which the first known complex, non-nomadic, agrarian civilization (that being Sumer) spread out from by influence. The history of Sumer is usually taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid, Uruk, and Jemdet Nasr periods. It appears that the archaeological culture of the Ubaidians' may have been derived from that of the Samarrans'.

Ever since the decipherment of the Sumerian cuneiform script; it has been the subject of much effort to relate it to a wide variety of languages. Proposals for linguistic affinity sometimes have a nationalistic background because it has a peculiar prestige as one of the most ancient written languages. Such proposals enjoy virtually no support among linguists because of their unverifiability. Some Assyriologists have argued that by examining the structure of the Sumerian language, its names for occupations; as well as, toponyms and hydronyms—one can suggest that there was once an ethnic group in the region that preceded the Sumerians. These pre-Sumerian people are now referred to as Proto-Euphrateans (or Ubaidians), and are theorized to have developed out of the culture centered at the Samarra Archaeological City (c. 6200 – c. 4700 BCE).

Proto-Euphratean is considered by some to have been the substratum language of the people that introduced farming into lower Mesopotamia during the Early Ubaid period (c. 5500 – c. 4500 BCE). Proto-Euphratean may have exerted an areal influence on it (especially in the form of polysyllabic words that sound un-Sumerian)—making researchers suspect them of being loanwords—and untraceable to any other known language. There is little speculation as to the affinities of this substratum language; therefore, it remains unclassified. Sumerian was once widely held to be an Indo-European language; but, that view later came to be almost universally rejected. It has also been suggested that Sumerian descended from a late prehistoric creole language.

Other scholars think that the Sumerian language may have originally been that of the hunting and fishing peoples who lived in the Mesopotamian Marshes and the Eastern Arabia littoral region; additionally, were part of the Arabian bifacial culture. Some archaeologists believe that the Sumerians lived along the Persian gulf coast of the Arabian Peninsula before a flood at the end of Last Glacial Period c. 10000 – c. 8000 BCE. Many scholars have proposed historical and genetic links between the present-day Marsh Arabs and the Sumerians of ancient Iraq based off of: their methods for house-building (mudhifs), homeland (Mesopotamian Marshes), and shared agricultural practices; however, there is no written record of the marsh tribes until the ninth century CE—and the Sumerians had already lost their distinct ethnic identity some 2,700 years prior.

A genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization (possibly as a result of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations). Sumerians (or at least some of them) may have been related to the original Dravidian population of India.

Elamite people

editSemitic people

editA Bayesian analysis suggested an origin for all known Semitic languages with a population of ancient Semitic-speaking peoples migrating from the Levant c. 3750 BCE; furthermore, spreading into Mesopotamia and possibly contributing to the collapse of the Uruk period c. 3100 BCE. Kish has been identified as the center of the earliest known East Semitic culture (the Kish civilization). This early East Semitic culture is characterized by linguistic, literary, and orthographic similarities extending across settlements such as Mari, Nagar, Abu Salabikh, and Ebla.

The similarities include the use of a writing system that contained non-Sumerian logograms, the use of the same system in naming the months of the year, dating by regnal years, and a measuring system (among many others). However, the existence of a single authority ruling those lands has not been assumed as each city had its own monarchical system, in addition to some linguistic differences for while the languages of Mari and Ebla were closely related, Kish represented an independent East Semitic linguistic entity that spoke a sort of dialect (Kishite), different from that of both the pre-Sargonic Akkadian and Eblaite languages. The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages, and is attested by three distinct languages: Kishite, Akkadian, and Eblaite (all of which have been long extinct). Kishite is the oldest known Semitic language.

Throughout the third millennium BCE, an intimate cultural symbiosis developed between Sumerians and Semites (which included widespread bilingualism). The influence of the Sumerian and East Semitic languages on each other is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a substantial scale to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and the East Semitic languages during the third millennium BCE as a sprachbund.

Languages

editLanguage isolates

editSumerian language

editEmegir variety

editEmesal sociolect

editProto-Euphratean language

editElamite language

editSemitic languages

editEast Semitic languages

editKishite language

editEblaite language

editMariote dialect

editAkkadian language

editWest Semitic languages

editAmorite language

editMathematics, measurement, writing, and timekeeping systems

editMathematics

editCuneiform

editSumerian cuneiform

editAkkadian cuneiform

editElamite cuneiform

editLiterature and other texts

edit| Publication date(s) | Language(s) | Text(s) | Genre(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian | Creation myth | |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian | Kesh temple hymn | Hymn |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Akkadian | Legend of Etana | Legend |

| c. 2600 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian and Eblaite |

Ebla tablets | Lexical lists Regnal lists Gazetteers |

| c. 2400 – c. 2200 BCE | Sumerian | Code of Urukagina | Legal code |

Elamite writing systems and scripts

editProto-Elamite script

editLinear Elamite

editCalendar

editReligion

editGods

editKing of the gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

Primordial gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abzu 𒍪𒀊 abzu |

— | Cosmic ocean | c. 5500 – c. 30 BCE |

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth | Earth | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nammu 𒀭𒇉 dnammu |

— | Motherhood | c. 2500 – c. 1300 BCE |

Divine triad

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

— | Weather | c. 3400 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Creation Water Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

Seven gods who decree

editFour primary gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

— | Weather | c. 3400 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Creation Water Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ |

— | Fertility | c. 3000 – c. 500 BCE |

Three sky gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

Venus | Love Beauty Justice War |

c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

Moon | Moon | c. 2600 BCE – c. 300 CE |

| Utu 𒀭𒌓 dutu |

Sun | Sun | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

Celestial bodies and gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utu 𒀭𒌓 dutu |

Sun | Sun | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

Mercury | Creation Water Knowledge |

c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

Venus | Love Beauty Justice War |

c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth | Earth | c. 3500 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

Moon | Moon | c. 2600 BCE – c. 300 CE |

| Nergal 𒀭𒆧𒀕𒀕 dnergalₓ(kiš.abg) |

Mars | Death | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| Marduk 𒀭𒀫𒌓 damar.ud |

Jupiter | Vegetation | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| An 𒀭 an |

Uranus or Saturn |

Sky | c. 4000 – c. 30 BCE |

Other major gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ereshkigal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲 dereš.ki.gal |

— | Chthonic | c. 2500 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ninurta 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁 dnin.urta |

— | Hunting | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

Minor gods

edit| Deity | Celestial body | Personifies | Dates of worship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meslamta-ea 𒀭𒈩𒇴𒋫𒌓𒁺 dmes.lam.ta.e₃ |

— | Divine twins | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Pabilsaĝ 𒀭𒉺𒄑𒉋𒊕 dpa.bil₃.saŋ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Bau 𒀭𒁀𒌑 dba.u₂ |

— | Health | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ninegal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒂍𒃲 dnin.e₂.gal |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 500 BCE |

| Lugal-Urub 𒀭𒈗𒌾 dlugal.urub |

— | — | c. 2500 – c. 1900 BCE |

| Nin-gublaga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒂯 dnin.gublaga |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Ištaran 𒀭𒅗𒁲 dištaran |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Nintinugga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒁷?𒂵 dnin.tin.ugₓ(ezenₓḫal).ga |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Shara 𒀭𒇋 dšara₂ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 700 BCE |

| Ninlil 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆤 dnin.lil₂ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ninazu 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀀𒍫 dnin.a.zu₅ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 600 BCE |

| Lisin 𒀭𒉈𒋜 dli₉.si₄ |

— | — | c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

Posthumously deified rulers of Sumer

edit| Deity | Dates of worship |

|---|---|

| Lugalbanda 𒀭𒈗𒌉𒁕 dlugal.banda₃da |

c. 2600 – c. 30 BCE |

| Ama-ušumgal-ana 𒀭𒂼𒃲𒁔 dama.ušumgal |

c. 2600 – c. 1300 BCE |

| Gilgamesh 𒀭𒄑𒉋𒂵𒈩 dgilgameš₄ |

c. 2600 – c. 1900 BCE |

Cosmology

editMetaphysical realms

edit| Realm | Placement | Inhabitants | Ruler | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totality 𒆠𒊹 ki.šar₂ |

An 𒀭 an |

Heaven 𒀭 an |

Gods 𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾 da.nun.na |

Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

| Ki 𒆠 ki |

Earth 𒈠 ma |

People 𒂟 erin₂ |

Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ | |

| Kur 𒆳 kur |

Netherworld 𒀭𒅕𒆗𒆷 dir.kal.la |

Ghosts 𒄇 gidim + Demons 𒋼𒇲 gal₅.la₂ |

Ereshkigal 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲 dereš.ki.gal | |

| Abzu 𒍪𒀊 abzu |

Primeval sea 𒇉 engur |

— | Nammu 𒀭𒇉 dnammu | |

Physical realms

editCentral realms (Sumer and Akkad)

edit| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akkad 𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠 a.ga.de₃ki |

Akkadians + Sumerians 𒊕𒈪𒂵 saŋ.gig₂.ga |

Akkadian + Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Kish 𒆧𒆠 kiški + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

Kishites + Sumerians 𒊕𒈪𒂵 saŋ.gig₂.ga |

Kishite + Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

Sumerians 𒊕𒈪𒂵 saŋ.gig₂.ga |

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Mountain of Eanna 𒆳 𒂍𒀭𒈾 kur e₂.an.na.bi + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

Sumerians 𒊕𒈪𒂵 saŋ.gig₂.ga |

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi | |

| Gu-Edin 𒄘𒂔𒈾 gu₂.edin.na + Kalam 𒌦 kalam + Sumer 𒆠𒂗𒄄 kien.gi₄ |

Sumerians 𒊕𒈪𒂵 saŋ.gig₂.ga |

Sumerian 𒅴𒄀 eme.gi |

Northern realms

edit| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Sea 𒅆𒉏𒈠𒊺 𒀀𒀊𒁀 igi.nim.ma.šea.ab.ba |

— | — | |

| Shubur 𒋚 šubur |

Subarians 𒋚 subur |

Kishite and Eblaite |

Eastern realms

edit| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Susiana 𒈹𒂞𒆠 šušinki |

Elamites 𒉏𒈠𒆠 elam.maki |

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Elam 𒉏𒆠 elamki |

Elamites 𒉏𒈠𒆠 elam.maki |

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Awan 𒀀𒉿𒀭𒆠 a.wa.anki |

Elamites 𒉏𒈠𒆠 elam.maki |

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Anshan 𒀭𒁺𒀭𒆠 an.ša₄.anki |

Elamites 𒉏𒈠𒆠 elam.maki |

Elamite 𒅴 𒉏𒈠𒆠 eme elam.maki | |

| Hamazi 𒄩𒈠𒍣𒆠 ḫa.ma.ziki |

— | — | |

| Gutium 𒄖𒋾𒌝𒆠 gu.ti.umki |

Gutians 𒄖𒋾𒌝𒆠 gu.ti.umki |

Gutian 𒅴𒄖𒋾𒌝 eme gu.ti.um | |

| Aratta 𒇶𒆠 arattaki |

— | — | |

| Shimashki 𒇻𒋢𒆠 šimaškiki |

— | — | |

| Marhasi 𒈥𒄩𒅆𒆠 mar.ḫa.šiki |

— | — | |

| Meluhha 𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠 me.luḫ.ḫaki |

Harappan civilization | Harappan language + Harappan script |

Southern realms

edit| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Sea 𒋝𒋫𒋫 𒀀𒀊𒁀 sig.ta.taa.ab.ba |

— | — | |

| Dilmun 𒉌𒌇 dilmunki |

— | — | |

| Magan 𒈣𒃶𒆠 ma₂.ganki |

— | — |

Western realms

edit| Region | (Proposed) Locations | People | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martu 𒈥𒌅 mar.tu |

Amorites 𒈥𒌅 mar.tu |

Amorite | |

| Sutium 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

Suteans 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

Sutean 𒋢𒋾𒌝 su.ti.um |

Government and administration

editTitles

edit| Sumerian title | Literal translation | European equivalent | Examples | Dates in use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lord of Sumer and king of all the land | King-Emperor | |||

| King of the land | Emperor | |||

| Lugal Kiski 𒈗𒆧𒆠 lugal |

Great king | |||

| Lugal 𒈗 lugal |

Big man | King | ||

| Nin 𒊩𒌆 ereš |

Queen | |||

| Nun 𒉣 nun |

Prince | |||

| Ensi 𒉺𒋼𒋛 ensi₂ |

Lord of the plowland | Governor | ||

| En 𒂗 en |

Lord | Lord | ||

| Lú 𒇽 lu₂ |

Man | |||

| Slave |

Law and order

editAnthropological evidence suggests that most societies before Sumer, along with most contemporary civilizations, were relatively egalitarian. Earlier periods of Sumer were also very egalitarian by nature, but that started to change with the rise of the ED. Sumerian culture was male-dominated and stratified. By the time the Akkadian Empire rose to power, patriarchy was a well-established cultural norm.

Sumerian myths suggested a prohibition against premarital sex. Marriages were often arranged by the parents of the bride and groom; engagements were usually completed through the approval of contracts recorded on clay tablets. These marriages became legal as soon as the groom delivered a bridal gift to his bride's father. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that premarital sex was a common, but surreptitious, occurrence. Prostitution existed but it is not clear if sacred prostitution did.

Code of Urukagina

editUrukagina of Lagash is best known for his reforms to combat corruption (the Code of Urukagina is sometimes cited as the earliest known example of a legal code in recorded history). The Code of Urukagina has also been widely hailed as the first recorded example of government reform, seeking to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality. Although the actual Code of Urukagina text has yet to be discovered, much of its content may be surmised from other references to it that have been found. In the Code of Urukagina: Urukagina exempted widows and orphans from taxes, compelled the city to pay funeral expenses (including the ritual food and drink libations for the journey of the dead into the lower world), and decreed that the rich had to use silver when purchasing from the poor, and if the poor does not wish to sell, the powerful man (the rich man or the priest) cannot force him to do so. The Code of Urukagina: limited the power of both the priesthood and large property owners, took measures against usury, burdensome controls, hunger, theft, murder, and seizure (of people's property and persons); as Urukagina stated: "The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man."

Despite these apparent attempts to curb the excesses of the elite class, it seems elite or royal women enjoyed even greater influence and prestige in Urukagina's reign than previously. Urukagina greatly expanded the royal "Household of Women" from about 50 persons to about 1,500 persons, then renamed it to "Household of Goddess Bau", gave it ownership of vast amounts of land confiscated from the former priesthood, and placed it under the supervision of Urukagina's wife (Shasha, or Shagshag). During the second year of Urukagina's reign, his wife presided over the lavish funeral of his predecessor's queen (Baranamtarra, who had been an important personage in her own right).

In addition to such changes, two of Urukagina's other surviving decrees have attracted controversy in recent decades:

- Urukagina seems to have abolished the former custom of polyandry in his country, on pain of the woman taking multiple husbands being stoned with rocks upon which her crime was written.

- In a statute where it was written: "If a woman says [text illegible...] to a man, her mouth is crushed with burnt bricks."

No comparable laws from Urukagina addressing penalties for adultery by men have survived. The discovery of these fragments has led some modern critics to assert that they provide: "The first written evidence of the degradation of women."

Reform Document

editThe following extracts are taken from the Reform Document:

- "From the border territory of Ningirsu to the sea, no person shall serve as officers."

- "For a corpse being brought to the grave, his beer shall be 3 jugs and his bread 80 loaves. 1 bed and 1 lead goat shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the person(s) take away."

- "When to the reeds of Enki a person has been brought, his beer will be 4 jugs, and his bread 420 loaves. 1 barig of barley shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the persons of... take away. 1 woman’s headband, and 1 sila of princely fragrance shall the eresh-dingir priestess take away. 420 loaves of bread that have sat are the bread duty, 40 loaves of hot bread are for eating, and 10 loaves of hot bread are the bread of the table. 5 loaves of bread are for the persons of the levy, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Girsu. 490 loaves of bread, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Lagash. 406 of bread, 2 mud vessels, and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the other lamentation singers. 250 loaves of bread and 1 mud vessel of beer are for the old wailing women. 180 loaves of bread and one mud vessel of beer are for the men of Nigin."

- "The blind one who stands in..., his bread for eating is 1 loaf, 5 loaves of bread are his at midnight, 1 loaf is his bread at midday, and 6 loaves are his bread in the evening."

- "60 loaves of bread, 1 mud vessel of beer, and 3 ban of barley are for the person who is to perform as the sagbur priest."

Economy, commerce, and trade

editThe Sumerian people used slaves; although, they were not a major part of the economy. Slave women worked as: pressers, weavers, millers, and porters.

Trade and commerce

editImports

editImports to Ur were being exported from many parts of the world. Discoveries of goods from far-away locations such as: obsidian (from Anatolia), lapis lazuli (from Badakhshan), beads (from Dilmun), and seals inscribed with the script (from the Indus Valley), suggest a remarkably wide-ranging network of ancient trade centered on the Persian gulf. Metals of all types had to be imported. Both Sumerian masons and jewelers knew and made use of: gold, silver, lapiz lazuli, chlorite, ivory, iron, and carnelian. The Epic of Gilgamesh referred to trade with far lands for goods (such as Lebanon cedar wood, which was scarce in Mesopotamia). The finding of resin in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, indicates that resin was traded from as far away as Mozambique. Sumerian potters decorated pots with paints made from cedar oil. The potters used a bow drill to produce the fire needed for baking the pottery.

Imports to Ur reflected the cultural and trade connections of the Sumerian city. During the EDIII, Ur was importing elite goods from geographically distant places. These objects included: precious metals (such as: gold and sliver) and semi-precious stones (such as: lapis lazuli and carnelian). These objects were all the more impressive considering the distance from which they traveled to reach Mesopotamia (and Ur, specifically). Mesopotamia was very well-suited for the agricultural production of plants and animals; however, was lacking in: metals, minerals, and stones.

The combination of these means of transportation allowed access to a vast trading network connecting distant places. Most of the gold known from archaeological contexts during the EDIII is concentrated at the royal cemetery of Ur. Textual evidence indicates that gold was reserved for prestige and religious functions. It was gathered in royal treasuries and temples, and used for the adornment of the elites as well as for the elites' funerary offerings (such as at the graves of the Royal Cemetery of Ur). Gold was used for personal ornaments, weapons, tools, sheet-metal cylinder seals, fluted bowls, goblets, imitation cockle shells, and sculptures.

Silver was mainly used for uncoined currency; but, it was also used for objects (which is the state in which silver is found at the royal cemetery of Ur). Silver was used for objects including: belts, vessels, hair ornaments, pins, weapons, cockle shells, and sculptures. There are very few literary references to sources for silver. It is also difficult to identify the actual origin of the silver and the mines from those areas in which the majority of trade occurred. Because silver was used as currency it is even more difficult to pinpoint an area of origination due to its vast circulation.

Lapis lazuli is the best-known and well-documented gemstone at Ur (and Mesopotamia in general). In the royal cemetery of Ur, lapis lazuli was discovered to have been used for: jewelry, plaques, gaming boards, lyres, ostrich-egg vessels, and also used for parts of a larger sculptural group referred to as the Ram in a Thicket. Some of the larger objects included a spouted cup, dagger-hilt, and whetstone. Because of its prestige and value, lapiz lazuli played a special role in cult practices and the term lapis-like is a commonly-occurring metaphor for unusual wealth and as an attribute used to described both deities and heroes. It has been commonly found associated alongside gold.

During the EDIII, chlorite stone artifacts were very popular (and thus traded very widely). Chlorite stone artifacts included disc beads, ornaments, and stone vases. These carved dark stone vessels have been found in ancient archaeological sites across all of Mesopotamia. They rarely exceeded twenty-five centimeters in height, and may have been filled with precious oils. They often carried both human and animal motifs inlaid with semi-precious stones.

-

A bowl made out of gold (dated to c. 2600 – c. 2300 BCE)

-

A diadem made out of gold ring pendants attached to a band of carnelian and lapis lazuli beads (dated to c. 2600 – c. 2500 BCE)

-

A pouring vessel made out of a shell imported from the Gulf of Oman (dated to c. 2700 – c. 2500 BCE)

Exports

editNatural resources

editCulture

editDaily life

editArts and crafts

editSculpting

editMetalworking and goldsmithing

editCylinder seals

editInlays

editFashion

editJewelry

edit-

Gold and lapis lazuli choker

-

Gold necklace

-

Gold pendant

-

Gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian garter

-

Gold finger rings

-

Lapis lazuli fish amulet

-

Lapis lazuli and carnelian cuff

Games

editMusic

editArchitecture

editDwellings

editMudbrick houses

editSumerian houses were usually large, rectangular, unwalled dwellings. They were constructed on stone foundations, with the houses themselves being made out of mudbricks. Wood, ashlar blocks, and rubble were also popular materials used to make houses. The mudbricks were made from clay and chopped straw. Sumerians used mudplaster for the walls; additionally, mud and poplar for the rooves.

Mesopotamian masonry was usually mortarless; although, asphalt was sometimes used. Brick styles, which varied greatly over time, are categorized by period. The favoured design was rounded bricks, which are somewhat unstable, so Mesopotamian bricklayers would lay a row of bricks perpendicular to the rest every few rows. The advantages to plano-convex bricks were the speed of manufacture as well as the irregular surface which held the finishing plaster coat better than a smooth surface from other brick types.

The larger, more complex houses had square centre rooms or long-roofed central hallways with other, smaller rooms attached to the central ones; but, a great variation in the size and materials used to build the houses suggest they were built by the inhabitants themselves. These houses could be tripartite, round, or rectangular. Such houses had courtyards and stairways leading to more rooms on second storeys and/or rooftops. These houses may have been the predecessors to the first religious, public, and domestic temples of Mesopotamia.

Reed huts

editThe smaller, simpler houses may not have coincided with the poorest people; in fact, it could be that the poorest people built houses out of perishable materials such as from reeds on the outskirts of settlements; however, there is very little direct evidence for this. Mudhifs (or reed huts) could be constructed out of bundles of reeds which would be tied to form parabolic arches (which make up the buildings' spines). These arches were strengthened by the pre-stressing of the columns, as they were initially inserted into the soil at opposing angles. Long cross beams of smaller, bundled reeds were laid across the arches and tied. The front and back walls were attached to two large vertical bundled reed columns and also made from woven mats.

Public buildings

editTemples and ziggurats

editThe precursors of ziggurats were raised platforms that date from the Ubaid period. Each ziggurat was part of a religious precinct that included other buildings. The ziggurats began as (usually oval, rectangular, or square-shaped) platforms. The ziggurats were mastaba-like structures with flat tops. The sun-baked bricks made up the core of the ziggurat with facings of fired bricks on the outside. Each step was slightly smaller than the step below it. The facings were often glazed in different colors and may have had astrological significance. The number of floors ranged from two to seven.

The urban nucleus of Eridu was the Eabzu ziggurat temple surrounded by the Mesopotamian Marshes near the ancient Persian gulf coastline. Four separate excavations at the site have demonstrated the existence of a shrine dated to the Ubaid period. The temple was expanded 18 times from c. 5300 – c. 300 BCE. On this basis it has been hypothesized that the tutelary deity of the temple was originally Abzu (later re-dedicated to Enki). Four separate excavations at the site of Eridu have demonstrated the existence of a shrine (with a surface area of 0.9 m2 (9.7 sq ft) c. 5300 BCE) located at the edge of a swamp that was expanded up to a surface area of 286 m2 (3,080 sq ft) by c. 3800 BCE.

Religious precincts

editTwo such religious precincts (or districts) were named after two gods of Sumerian religion: Anu (the Anu or Kullaba district) and Inanna (the Eanna district). The two districts merged to form a city known to the Sumerians as Uruk c. 5000 – c. 4000 BCE. It was at Uruk that the Sumerians began construction of the Anu ziggurat c. 4000 – c. 3500 BCE. The ziggurat reached to be 13 metres (43 feet) high c. 4000 – c. 3500 BCE and remained the world's tallest freestanding structure for over a thousand years until surpassed by the pyramid of Djoser. The design of Egyptian pyramids (especially the stepped designs of the oldest pyramids) may have been an evolution from the ziggurats built in Mesopotamia.

Tells

editIn order to harden mudbricks; they were baked out in the Sun to dry. These types of bricks are much less durable than oven-baked ones; so, buildings eventually deteriorated. They were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This planned structural life cycle gradually raised the level of cities, so that they came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resulting mounds are known as tells, and are found throughout the Near East.

Sites

editList

edit| Ancient name | Modern name | Temple | Tutelary deity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu 𒉣𒆠 eridugki |

Tell Abu Shahrain | Eabzu 𒂍𒍪𒀊 e₂.abzu |

Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 den.ki |

| Kuara 𒀀𒄩𒆠 kuara₂ki |

Tell al-Lahm | Nergal 𒀭𒆧𒀕𒀕 dnergalₓ(kiš.abg) | |

| Ur | Tell al-Muqayyar | 𒂍𒆧𒉡𒅅 e₂.kiš.nu.ŋal₂ |

Nannar 𒀭𒋀𒆠 dnanna |

| Kesh 𒋙𒀭𒄲𒆠 keš₃ki |

Ninhursag 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 dnin.ḫur.saŋ | ||

| Larsa 𒌓𒀕𒆠 larsamki |

Tell as-Senkereh | Ebabbar 𒂍𒌓𒌓 e₂.babbar₂ |

Utu 𒀭𒌓 dutu |

| Uruk | Tell al-Warka | Eanna 𒂍𒀭𒈾 e₂.an.na |

An 𒀭 an |

| Bad-tibira 𒂦𒁾𒉄𒆠 bad₃.tibiraki |

Emush 𒂍𒈹 e₂.muš₃ |

Ama-ušumgal-ana 𒀭𒂼𒃲𒁔 dama.ušumgal | |

| Lagash 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 lagaški |

Tell al-Hiba | Eninnu 𒂍𒐐 e₂.ninnu |

Ningirsu 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁 dnin.urta |

| Girsu 𒄈𒋢𒆠 ŋir₂.suki |

Tell Telloh | ||

| Umma | Tell Jokha | Emah 𒂍𒈤 e₂.maḫ |

Shara |

| Zabala | Tell Ibzeikh | Ezi-kalam-ma | |

| Nippur | Tell Nuffar | Ekur 𒂍𒆳 e₂.kur |

Enlil 𒀭𒂗𒆤 den.lil₂ |

| Shuruppak | Tell Fara | E-dimgalanna | Sud |

| Marad 𒀫𒁕𒆠 marad.daki |

Tell Wannat es-Sadum | ||

| Adab 𒌓𒉣𒆠 adabki |

Tell Bismaya | Eshar 𒂍𒊬 e₂.šar |

Inanna 𒀭𒈹 dinana |

| Isin 𒅔𒆠 isin₂ki |

Ishan al-Bahriyat | E-ni-dub-bi | Nintinugga 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒁷?𒂵 dnin.tin.ugₓ(ezenₓḫal).ga |

| Kisurra 𒆠𒋩𒊏 kisur.ra |

Tell Abu Hatab | ||

| Eresh 𒉀𒆠 ereš₂ki |

Tell Abu Salabikh | Baal | |

| Dilbat 𒌓𒉣𒆠 dil.batki |

Tell ed-Duleim | E-ibe-anu | Urash |

| Larak 𒆷𒊏𒀝𒆠 la.ra.agki |

Pabilsaĝ | ||

| Kish 𒆧𒆠 kiški |

Tell Uheimir | E-dub | Zababa |

| Kutha | Tell Ibrahim | E-meslam | |

| Urum | E-ab-lu-a | Suen | |

| Sippar | Tell Abu Habbah | E-babbar | Utu |

| Sippar-Amnanum | Tell ed-Der | ||

| Der 𒂦𒆠 durumki |

al-Badra | E-dim-gal-kalama | Ištaran |

| Akshak 𒌔𒆠 akšakki |

|||

| Akkad 𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠 a.ga.de₃ki |

E-an-da-di-a | ||

| Tutub | Tell Khafajah | Temple of Nintu | Nintu |

| Eshnunna 𒀊𒉣𒈾𒆠 eš₃.nun.naki |

Tell Asmar | Esikil 𒂍𒂖 e₂.sikil |

Tishpak and Ninazu |

Map

editTechnology

editExamples of Sumerian technology include: the wheel, cuneiform script, arithmetic and geometry, irrigation systems, Sumerian boats, lunisolar calendar, bronze, leather, saws, chisels, hammers, braces, bits, nails, pins, rings, hoes, axes, knives, lancepoints, arrowheads, swords, glue, daggers, waterskins, bags, harnesses, armor, quivers, war chariots, scabbards, boots, sandals, harpoons and beer. The Sumerians had three main types of boats:

- clinker-built sailboats stitched together with hair, featuring bitumen waterproofing

- skin boats constructed from animal skins and reeds

- wooden-oared ships, sometimes pulled upstream by people and animals walking along the nearby banks

Agriculture, domestication, and hunting

editAgriculture

editAgriculture depended heavily on irrigation. Irrigation was accomplished by the use of shaduf, canals, channels, dykes, weirs, and reservoirs. The frequent, violent floods of the Tigris (and less so) of the Euphrates rivers meant that canals required frequent repair and continual removal of silt—and survey markers and boundary stones needed to be continually replaced. The government required individuals to work on the canals in a corvée; although, the rich were able to exempt themselves. The Mesopotamians practiced similar irrigation techniques as those used by ancient Egyptians. Anthropologists say that irrigation development was associated with urbanization, and that 89% of the population lived in the cities.

Lower Mesopotamia is associated with intensive, irrigated, hydraulic agriculture; and, the use of the plough (both introduced from Upper Mesopotamia). The Sumerian people adopted a rural lifestyle perhaps as early as c. 5500 – c. 3300 BCE. Sumer demonstrated a number of core agricultural techniques, including: organized irrigation, large-scale intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping (involving the use of plough agriculture); and, the use of an agricultural specialized labor force under bureaucratic control. The necessity to manage temple accounts with this organization led to the development of writing (c. 3500 – c. 3100 BCE).

Mesopotamian houses had enclosed gardens with trees and other plants; wheat (emmer and einkorn) and probably other cereals were sown in the fields. Plants were also grown in pots or vases. Mesopotamians also grew barley (two-rowed), pulses, beans, and spices (lentils, chickpeas, and mustard), fruits (apples, dates, and figs), and vegetables (onions, garlic, lettuce, and leeks). Sumer was among the earliest known beer-drinking societies. Cereals were plentiful and were the key ingredient in their early brew. They brewed multiple kinds of beer consisting of wheat, barley, and mixed grain beers.

Animal husbandry

editThe Standard of Ur (dated to c. 2600 – c. 2350 BCE) suggests that bovids (sheep, goats, and cattle) and suids (pigs) were domesticated to be used as livestock—raised as draught animals and/or to produce commodities (wool, milk, meat, and manure). Mesopotamians also used both war and pack animals (equids such as: Asiatic wild asses, African wild asses, donkeys, crossbreeds, and/or hybrids). A dog breed of sighthound (saluki) appeared in Mesopotamia c. 7000 – c. 2000 BCE. Sumerians hunted both small (rabbits), and big game (wild asses, wild boars, wild sheep, wild goats, and deer); as well as, catching fish and fowl. Waterfowl such as ducks and geese were kept in captivity.

-

A photographic image detailing the "peace" panels on the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a man leading a ram on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a man and three goats on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of two men leading a bovid on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of two men leading an equid on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of men carrying offerings on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

-

Detail of a feast on the peace panels of the Standard of Ur.

Tools and utensils

editKnives, drills, wedges and an instrument that looks like a saw were all known.

War and peace

editMilitary systems

editWeapons and armor

editBlunt instruments (such as clubs, staves, maces, and hammers), pole weapons (e.g. spears and scythes), bladed weapons (like axes, knives, daggers, and sickle-swords), and ranged weapons (including javelins, throwing sticks, throwing axes, slings, bow and arrows) were all employed in war. Soldiers wore helmets composed of either copper or bronze; additionally, armor (cloaks studded in metal discs) and shields.

-

Copper alloy axe

-

Copper alloy crescent-shaped axehead

-

Gold spearhead and copper alloy bow ends

-

Copper alloy dagger and silver spearhead

-

Copper alloy lanceheads

-

Copper alloy harpoons

-

Gold spearhead

Military history of Mesopotamia

editWarfare in Lower Mesopotamia

editLagash-Umma border conflict

editThe first war in Sumerian recorded history was between the two city-states of Lagash and Umma (an intermittent, border war which may have lasted nearly 200 years from c. 2525 – c. 2342 BCE) as described on the Stele of the Vultures. The stele shows the king of Lagash (Eannatum r. c. 2457 – c. 2425 BCE) leading an army (consisting mainly of infantrymen). The infantrymen were primarily armed with spears, carried wooden/wicker, rectangular shields, and wore: caps (made out of leather) underneath helmets composed of either copper or one of its alloys (e.g. arsenic for arsenical bronze, or tin). Depictions of the light infantrymen show them wearing: kaunakes (short woollen mantles with tufts of feathers sown onto them and worn like unisex wraparound skirts); as well as, armor (cloaks of sheepskin on their backs studded in metal discs or plates), and no body armor protecting their torsos. The spearmen are shown arranged in what resembles the phalanx formation, which requires training and discipline; this implies that the Sumerians may have made use of professional soldiers.

The armies of the city-states could each have up to 3,600—5,400 soldiers. The organization of their armies was based on multiples of 6 (60, 120, 600, etc.) These large armies would consist of many military units. One military unit known as the nu.banda contained anywhere from 60—120 erin (conscripts, laborers, or soldiers) and may have been led by an ugula (overseer or commander). Other known units include the shublugal.

To support the main army there would be four-wheeled war wagons each with two-man crews. One crewman would be the driver and the other; a soldier (armed with a lance or battle axe). Each wagon was pulled by four Asiatic wild asses. These early wheeled vehicles functioned less effectively in combat than did the much later chariots, and some have suggested that these wagons served primarily as transports. The cabless cart was composed of a woven basket and the wheels had solid three-piece designs.

The near-constant warfare among the city-states of Sumer helped the Mesopotamians develop their military technology and techniques to a high level. Sumerian city-states were surrounded by defensive walls. The Sumerians engaged in siege warfare between their cities; but, the mudbrick walls were able to deter some foes. Soldiers would besiege cities using battering rams and sappers.

Warfare in Upper Mesopotamia

editMari-Ebla war

editHistory of Mesopotamia (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BCE)

editSumerian civilization (c. 5500 – c. 1792 BCE)

edit| c. 5500 BCE–c. 1792 BCE | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Civilization | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | No single/fixed capital

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era |

| ||||||||||||||||||

• Developed | c. 5500 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||

• Transitioned | c. 1792 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Ur (c. 3800 – c. 500 BCE)

editUr I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2400 BCE)

editThe first dynasty of Ur is dated to c. 2600 – c. 2350 BCE. It was preceded by the first dynasty of Uruk on the Sumerian King List (SKL). Only four of the final kings of the first dynasty of Ur are mentioned on the SKL. The first dynasty may have been preceded by one other dynasty of Ur unnamed on the SKL which had extensive influence over the area of Sumer, and apparently led a union of lower Mesopotamian polities. Ur may have had <6,000 citizens c. 2800 BCE.

Ur-Pabilsag is the earliest known ruler of Ur said to have held the Sumerian title for king. He was preceded by his father A-Imdugud (who ruled over Ur with the Sumerian title for governor) and succeeded by his son Meskalamdug (who r. c. 2600 – c. 2550 BCE as a king). Mesannepada (r. c. 2500 BCE) is the first king of Ur listed on the SKL. Two other rulers earlier than Mesannepada are known from other sources, namely Puabi (probably r. c. 2550 BCE with the Sumerian title for queen) and Akalamdug (r. c. 2600 – c. 2550, c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE as king). It would seem that both Akalamdug and Mesannepada may have been sons of Meskalamdug, according to an inscription found on a bead in Mari and Meskalamdug may have been the true founder of the first dynasty.

Mesilim (r. c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE) may have enjoyed suzerainty over both Ur and Adab. He is also mentioned in some of the earliest monuments as arbitrating a border dispute between Lagash and Umma. Mesilim's placement before, during, or after the reign of Mesannepada in Ur is uncertain, owing to the lack of other synchronous names in the inscriptions, and his absence from the SKL. Some have suggested that Mesilim and Mesannepada were in fact one and the same; however, others have disputed this theory. Both Mesilim and Mesannepada also seem to have subjected Kish, thereafter assuming the title king of Kish for themselves. The title king of Kish would be used by many kings of the preeminent dynasties for some time afterward.

Mesannepada (r. c. 2500 BCE) is the first king of Ur listed on the SKL. Mesannepada may have been a son of king Meskalamdug, according to an inscription found on a bead in Mari, and Meskalamdug may have been the true founder of the first dynasty. Some have suggested that Mesilim and Mesannepada were in fact one and the same; however, others have disputed this theory. Both Mesilim and Mesannepada also seem to have subjected Kish, thereafter assuming the title king of Kish for themselves. The title king of Kish would be used by many kings of the preeminent dynasties for some time afterward.

The Royal Cemetery at Ur held the tombs of several rulers of the first dynasty of Ur. The tombs are particularly lavish, and testify to the wealth of the first dynasty. One of the most famous tombs is that of Puabi. The artifacts found in the royal tombs of the dynasty show that foreign trade was particularly active during this period, with many materials coming from foreign lands, such as carnelian likely coming from the Indus or Iran, lapis Lazuli from the Badakhshan area of Afghanistan, silver from Turkey, copper from Oman, and gold from several locations such as Egypt, Nubia, Turkey or Iran. Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600-2450, in an example of Indus-Mesopotamia relations. In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique developed by the Harappans. These materials were used into the manufacture of beautiful objects in the workshops of Ur.

The Ur I dynasty had enormous wealth as shown by the lavishness of its tombs. This was probably due to the fact that Ur acted as the main harbour for trade with India, which put her in a strategic position to import and trade vast quantities of gold, carnelian or lapis lazuli. In comparison, the burials of the kings of Kish were much less lavish. High-prowed Summerian ships may have traveled as far as Meluhha, thought to be the Indus region, for trade.

Ur II dynasty (c. 2400 – c. 2340 BCE)

editThe rulers from the second dynasty of Ur may have r. c. 2400 – c. 2340 BCE. It was preceded by the second dynasty of Uruk on the SKL. Only two, three, or four rulers are mentioned: Nanni, Meskiagnun (son of Nanni), and two unnamed rulers with unknown fathers. Likewise on the SKL: the second dynasty of Ur was succeeded by a dynasty from Adab. Little more is otherwise known about this dynasty; in fact, the once supposed second dynasty of Ur may have never existed.

Uruk (c. 5000 BCE – c. 700 CE)

editUruk II dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2355 BCE)

editEnshakushanna (r. c. 2440 – c. 2430, c. 2430 – c. 2400 BCE) was said to have reigned for sixty years on the SKL. An inscription stated that his father was "Elili" (possibly Elulu of the first dynasty of Ur). He is said to have conquered Ur, Akshak, Kish (where he overthrew Enbi-Ishtar), Akkad, Hamazi, and Nippur—effectively claiming hegemony over all of Sumer and adopting the title Lord of Sumer and King of all the Land. He was preceded by three rulers who r. c. 2500 – c. 2440, c. 2450 – c. 2430 BCE: Lugalnamniršumma, Lugalsilâsi, and Urzage (all of whom assumed the title king of Kish; nonetheless, neither are mentioned on the SKL). He was succeeded by Lugalkinishedudu (r. c. 2430 – c. 2365, c. 2400 – c. 2350 BCE).

Lugalkinishedudu may have retained some of the power inherited by his predecessors—which included rule over Uruk, Ur, and assumed the title king of Kish. The oldest known written mention of a peace treaty between two kings is on a clay nail found in Girsu, commemorating the alliance between Lugalkinishedudu and Entemena of Lagash.

Uruk III dynasty (c. 2355 – c. 2330 BCE)

editUrukagina was overthrown and his city Lagash captured by Lugalzagesi (r. c. 2355 – c. 2330, c. 2340 – c. 2316 BCE), the governor of Umma. Lugalzagesi also took Ur, Adab, Larsa, Nippur, Kish, Zabala, Ki’ana, and made Uruk his capital. In a long inscription that he made engraved on hundreds of stone vases dedicated to the god Enlil of Nippur, he boasts that his kingdom extended "from the Lower Sea, along the Tigris and Euphrates, to the Upper Sea." He in turn was overthrown by Sargon of Akkad.

Lagash (c. 2600 – c. 2030 BCE)

editLagash I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2342 BCE)

editThe rulers of this dynasty are believed to have r. c. 2570 – c. 2350, c. 2494 – c. 2342 BCE. Although the first dynasty of Lagash has become well-attested through several important monuments, many archaeological finds, and well-known based off of mentions on inscriptions contemporaneous with other dynasties from the EDIII period; it was not inscribed onto the SKL. One fragmentary supplement names the rulers of Lagash. The first dynasty of Lagash preceded the dynasty of Akkad in a time in which Lagash exercised considerable influence in the region.

Enhengal (r. c. 2570 – c. 2510, c. 2530 – c. 2510 BCE) is recorded as the first known ruler of Lagash, being tributary to Uruk. His successor Lugalshaengur (r. c. 2510 – c. 2494 BCE) was similarly tributary to Mesilim. Following the hegemony of Mesannepada, Ur-Nanshe (r. c. 2494 – c. 2465 BC) succeeded Lugalshaengur as the new high priest of Lagash and achieved independence, making himself king. He defeated Ur and captured the king of Umma, Pabilgaltuk. In the ruins of a building attached by him to the temple of Ningirsu, terracotta bas reliefs of the king and his sons have been found, as well as onyx plates and lions' heads in onyx reminiscent of Egyptian work. One inscription states that ships of Dilmun (Bahrain) brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands. He was succeeded by his son Akurgal (r. c. 2466 – c. 2457, c. 2464 – c. 2455 BCE).

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of Eannatum (r. c. 2457 – c. 2425, c. 2455 – c. 2425 BCE), grandson of Ur-Nanshe, who made himself master of the whole of the country of Sumer by annexing the cities of Uruk, Ur, Nippur, Akshak, and Larsa. Umma was made tributary (after he vanquished Ush)—a certain amount of grain being levied upon each person in it, that had to be paid into the treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ningirsu; in addition, Eannatum's campaigns extended beyond the confines of Sumer as he overran a part of Elam, took the city of Az on the Persian gulf, and exacted tribute as far as Mari. Many of the realms he conquered were often in revolt; furthermore, he seems to have used terror as a matter of policy. His Stele of the Vultures depicts vultures pecking at the severed heads and other body parts of his enemies. During his reign, temples and palaces were repaired or erected at Lagash and elsewhere; the town of Nina—that probably gave its name to the later Niniveh—was rebuilt, and canals and reservoirs were excavated. He also annexed the kingdom of Kish; however, it recovered its independence after his death. His empire collapsed shortly after his death.

Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, Enannatum I (r. c. 2424 – c. 2421, c. 2425 – c. 2405 BCE). During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Illi, who also attacked Lagash.

His son and successor Entemena (r. c. 2420 – c. 2393, c. 2405 – c. 2375 BCE) restored the prestige of Lagash. Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre. A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the eagle crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained. A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur. After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt rulers is attested for Lagash: Enannatum II, Enentarzi, Enlitarzi, and Lugalanda who altogether r. c. 2392 – c. 2361, c. 2375 – c. 2352 BCE. The last of these, Urukagina (r. c. 2361 – c. 2350, c. 2352 – c. 2342 BCE), was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms (as part of the Code of Urukagina), and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He was the last ethnically Sumerian king before Sargon of Akkad.

Umma (c. 2600 – c. 2022 BCE)

editUmma I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2355 BCE)

editUmma was an ancient city in Sumer best known for its century-long border war against Lagash over the Gu-Edin plain between Umma's earliest known ruler Pabilgagaltuku (r. c. 2600 – c. 2520, c. 2535 – c. 2455 BCE) and Lagash's Ur-Nanshe. Pabilgagaltuku was subsequently defeated, seized, vanquished by Ur-Nanshe and succeeded by a governor Ush (r. c. 2520 – c. 2441, c. 2455 – c. 2445 BC). Ush is mentioned on the Cone of Entemana as having violated the frontier with Lagash—a frontier which had been solemly established by king Mesilim of Kish. It is thought that Ush was severely defeated by Eannatum. The Stele of the Vultures suggests that Ush was killed in a rebellion in his capital city of Umma after the loss of 3,600 soldiers on the field.

Adab (c. 2600 – c. 1760 BCE)

editAdab dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 1760 BCE)

editNin-kisalsi (r. c. 2550 BCE) was a governor of Adab and probably the suzerain of Mesilim. Nin-kisalsi may have been succeeded by Lugaldalu. Following this period, the region of Mesopotamia seems to have come under the sway of Lugalannemundu (r. c. 2350 BCE). According to inscriptions, king Lugalannemundu of Adab is said to have subjugated the Four Quarters of the World. However, his empire fell apart with his death; the SKL indicates that Mari in upper Mesopotamia was the next city to hold the hegemony.

Elamite civilization (c. 3200 BCE – c. 224 CE)

editAwan (c. 2600 – c. 2100 BCE)

editAwan dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2100 BCE)

editAccording to the SKL: a dynasty from Awan exerted hegemony in Sumer after defeating the first dynasty of Ur. It mentions three Awanite kings, who supposedly reigned for a total of 356 years. Their names have not survived on the extant copies, apart from the partial name of the third king, "Ku-ul...", who it says ruled for 36 years. A separate regnal list discovered in Susa names an additional twelve Elamite rulers beside the three on the SKL: Peli, Tata, Ukku-Tanhish, Hishutash, Shushun-Tarana, Napi-Ilhush, Kikkutanteimti, Luh-ishan, Hishep-Ratep, Helu, Khita, and Puzur-Inshushinak. Some have suggested that the first three on the Susanian dynastic list may have been the same three on the SKL said to have ruled over both Elam and Sumer.

The dynasty of Awan was the first from Elam of which anything is known today. The dynasty corresponds to the Old Elamite period (c. 2700 – c. 1600 BCE). Awan was a city-state or possibly a region of Elam with an uncertain location, but it has been variously conjectured to have been in the: Khuzestan, Kermanshah, Lorestan, Ilam, and/or Fars provinces of Iran. This dynasty may have exerted hegemony in Sumer after defeating Ur at some point c. 2600 – c. 2400 BCE, and may have continued ruling independently over Elam from Awan up until c. 2220 – c. 2100 BCE after losing the hegemony. This information is not considered reliable, but it does suggest that Awan had political importance in the 3rd millennium BCE.

As there are very few other sources for this period, most of these names are not certain. Little more of these rulers' reigns is known, but the Elamites were likely major rivals of neighboring Sumer from remotest antiquity; they were said to have been defeated by Enmebaragesi, who is the earliest archaeologically attested Sumerian king, as well as by a later monarch, Enannatum I. It is also known that the Elamites carried out incursions into Mesopotamia, where they ran up against the most powerful city-states of this period, Kish and Lagash. One such incident is recorded in a tablet addressed to Enetarzi, a minor ruler or governor of Lagash, testifying that a party of 600 Elamites had been intercepted and defeated while attempting to abscond from the port with plunder.

Luh-ishan (r. c. 2350 – c. 2331, c. 2350 – c. 2320 BCE) is the eighth ruler on the Susanian dynastic list, while his father's name "Hishiprashini" is a variant of that of the ninth listed ruler, Hishepratep—indicating either a different individual or (if the same)—that the order of rulers on the Susanian dynastic list has been jumbled. Events become a little clearer at the time of the Akkadian empire, when historical texts tell of campaigns carried out by the kings of Akkad on the Iranian plateau. Luh-ishan was a vassal of Sargon of Akkad around the time that Sargon boasted of defeating Luh-ishan. Sargon's son and successor (Rimush) is said to have conquered Elam, defeating its king named Emahsini. Khita may have signed a peace treaty with Naram-Suen of Akkad c. 2280 BCE.

After the death of Emahsini, Elam became a vassal state ruled by several Akkadian governors. Among these governors were: Eshpum, Epirmupi, and Ili-ishmani. The last two ruled with both the Sumerian title for governor and the Akkadian title for military governor. They r. c. 2300 – c. 2153, c. 2270 – c. 2154 BCE.

Hamazi (c. 2600 – c. 2010 BCE)

editHamazi dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2010 BCE)

editHamazi first came to the attention of archaeologists with the discovery of a vase with an inscription in very archaic cuneiform commemorating the victory of Uhub (r. c. 2570 – c. 2550 BCE as an early ruler of Kish) over Hamazi, resulting in speculation that Hamazi was to be identified with Carchemish (in Syria). Its exact location is unknown; but, it's now generally considered to have been located somewhere along the vicinity of the Diyala river and/or the western region of the Zagros mountains—possibly near Nuzi (in Iraq) or Hamadan (in Iran). The earliest mention of Hamazi is on the Bowl of Utu (dated to c. 3245, 2750, or 2600 BCE). It was also mentioned in two legends: Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta and Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana.

A copy of a diplomatic message sent from Irkab-Damu (r. c. 2340 BCE as the malikum of Ebla) to Zizi (r. c. 2450 BCE as a ruler of Hamazi) was found among the Ebla tablets. According to the SKL, king Hadanish of Hamazi (r. c. 2450 – c. 2430 BCE) held the hegemony over Sumer after defeating Kish; however, he was in turn defeated by Enshakushanna of Uruk.

Hamazi was one of the provinces under the reign of Amar-Suen (r. c. 2047 – c. 2038, c. 2046 – c. 2038 BCE) of the third dynasty of Ur. Ur-Adad, Lu-nanna (son of Nam-mahani), Ur-Ishkur, and Warad-Nannar may have ruled as governors of Hamazi up until the province was plundered c. 2010 BCE by Ishbi-Erra (r. c. 2018 – c. 1985, c. 2017 – c. 1985 BC) of Isin. The rulers of Hamazi are believed to have r. c. 3245 – c. 2010 BCE.

Kish civilization (c. 3100 – c. 2350 BCE)

editKish (c. 3750 BCE – c. 1200 CE)

editKish II dynasty (c. 2585 – c. 2430 BCE)

editTwo rulers (neither appear on the SKL) are known to have ruled from Kish in between the first and second dynasties: Uhub (r. c. 2570 – c. 2550 BCE) and Mesilim (r. c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE). The SKL names another eight kings for this dynasty: Susuda, Dadasig, Mamagal, Kalbum, Tuge, Mennuna, Enbi-Ishtar, and Lugalngu. Next to nothing is known about the aforementioned eight.

Kish III dynasty (c. 2430 – c. 2360 BCE)

editThe third dynasty of Kish is unique in that it is represented by a woman named Kubaba (r. c. 2450 – c. 2365, c. 2430 – c. 2350 BCE). The SKL adds that she had been a tavern-keeper before overthrowing the hegemony of Mari and becoming monarch. According to the Weidner Chronicle: the god Marduk handed over the kingship to Kubaba of Kish during the reign of Puzur-Nirah of Akshak; although, according to the SKL: the Akshak dynasty succeeded the third of Kish. Although its military and economic power was diminished, Kish retained a strong political and symbolic significance. Just as with Nippur to the south, control of Kish was a prime element in legitimizing dominance over the north of Mesopotamia (Assyria and/or Subartu).

Kubaba's dynasty is sometimes said to include her son Puzur-Suen (r. c. 2365 – c. 2340 BC) and grandson Ur-Zababa (r. c. 2340 – c. 2334 BC). The SKL ascribes a 100-year-long reign for the matriarch, 25 for her son, and (varyingly) 4, 6, or even up to 400 years to her grandson. Altogether they ruled for 131 years.

Sargon of Akkad came from an area near Kish called Azupiranu. He would later declare himself the king of Kish, as an attempt to signify his connection to the religiously important area. Because of the city's symbolic value, strong rulers later claimed the traditional title "king of Kish", even if they were from Akkad, Ur, Assyria, Isin, Larsa, or Babylon. Kubaba was later deified as the goddess Kheba.

Kish IV dynasty (c. 2360 – c. 2254 BCE)

editThe kings of the fourth dynasty of Kish are believed to have r. c. 2360 – c. 2254, c. 2340 – c. 2254 BCE. Some versions of the SKL lists 6, 7, or 8 kings (including the son and grandson of Kubaba from the third dynasty). Beside the aforementioned two related to the third dynasty, there is: Zimudar, Usiwater, Eshtar-muti, Ishme-Shamash, Shu-ilishu, Nanniya. Zimudar and his successors seem to have been vassals for Sargon of Akkad, and there is no evidence that they ever exercised hegemony in Sumer.

Mari (c. 2900 – c. 300 BCE)

editMari I dynasty (c. 2900 – c. 2550 BCE)

editMari did not start off as a small settlement that later grew; but, more of a planned city that was founded c. 2900 BCE (by Sumerians or possibly even by East Semites) to control the waterways of the trade routes along the Tigris–Euphrates river system. The city was built about 1 to 2 kilometers away from the Euphrates river to protect it from floods, and was connected to the river by an artificial canal that was between 7 and 10 kilometers long, depending on which meander it used for transport, which is hard to identify today. The city is difficult to excavate as it is buried deep under later layers of habitation. A defensive system against floods composed of a circular embankment was unearthed, in addition to a circular 6.7 m thick internal rampart to protect the city from enemies. An area 300 meters in length filled with gardens and craftsmen quarters separated the outer embankment from the inner rampart, which had a height of 8 to 10 meters and was strengthened by defensive towers. Other findings include one of the city gates, a street beginning at the center and ending at the gate, and residential houses. Mari had a central mound, but no temple or palace has been unearthed there. A large building was however excavated (with dimensions of 32 meters X 25 meters) and seems to have had an administrative function. It had stone foundations and rooms up to 12 meters long and 6 meters wide. The SKL records a dynasty of six kings from Mari enjoying hegemony between the first of Adab and the third of Kish: Anbu, Anba, Bazi, Zizi, Limer, and Sharrumiter. It has been suggested that only Sharrumiter held the hegemony after Lugalannemundu. The city was abandoned c. 2550 BCE for reasons unknown.

Mari II dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2330 BCE)

editThe names of the kings from the first Mariote kingdom were damaged on earlier copies of the SKL, and those kings were correlated with historical kings that belonged to the second kingdom. However, an undamaged copy of the SKL that dates to the old Babylonian period was discovered in Shubat-Enlil, and the names bear no resemblance to any of the historically-attested rulers of the second Mariote kingdom, indicating that the compilers of the SKL had an older (and probably legendary) dynasty in mind that predates the second kingdom

The rulers of the second Mariote kingdom held the Sumerian title for king, and many are attested in the city, the most important source being a letter written by king Enna-Dagan c. 2350 BCE to Irkab-Damu of Ebla. The chronological order of the kings from the second kingdom era is highly uncertain; nevertheless, it is assumed that the letter of Enna-Dagan lists them in a chronological order. Many of the kings were attested through their own votive objects discovered in the city, and the dates are highly speculative. The kings of the second Mariote kingdom may have r. c. 2550 – c. 2290, c. 2450 – c. 2260 BCE.

The earliest attested king in the letter of Enna-Dagan is Ansud, who is mentioned as attacking Ebla, the traditional rival of Mari with whom it had a century-long war, and conquering many of Ebla's cities, including the land of Belan. The next king mentioned in the letter is Saʿumu (r. c. 2416 – c. 2400 BCE), who conquered the lands of Ra'ak and Nirum. King Kun-Damu (r. c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Ebla defeated Mari in the middle of the 25th century BCE. The war continued with Ishtup-Ishar (r. c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Mari's conquest of Emar at a time of Eblaite weakness in the mid-24th century BCE. King Igrish-Halam (r. c. 2360 – c. 2340 BCE) of Ebla had to pay tribute to Iblul-Il (r. c. 2425 – c. 2400, c. 2400 – c. 2380 BCE) of Mari, who is mentioned in the letter, conquering many of Ebla's cities and campaigning in the Burman region.

Enna-Dagan also received tribute; his reign fell entirely within the reign of Irkab-Damu of Ebla, who managed to defeat Mari and end the tribute. Mari defeated Ebla's ally Nagar in year seven of the Eblaite vizier Ibrium's term, causing the blockage of trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia. The war reached a climax when the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish made an alliance with Nagar and Kish to defeat Mari in a battle near Terqa. Ebla itself suffered its first destruction a few years after Terqa c. 2300 BCE, during the reign of the Mariote king Hidar. According to Alfonso Archi, Hidar was succeeded by Ishqi-Mari whose royal seal was discovered. It depicts battle scenes, causing Archi to suggest that he was responsible for the destruction of Ebla while still a general.

Akshak (c. 2600 – c. 2330 BCE)

editAkshak dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2330 BCE)

editAkshak achieved independence with a line of five or six kings extending from Unzi, Undalulu, Urur to Puzur-Nirah, Ishu-Il, and Shu-Suen (son of Ishu-Il). These kings of Akshak r. c. 2459 – c. 2360 BCE before being defeated by the kings in the fourth dynasty of Kish. One ruler preceding Unzi by the name of Zuzu (r. c. 2470 BCE) may have been smited by Eannatum of Lagash.

Ebla (c. 3500 BCE – c. 600 CE)

editEbla I dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2290 BCE)

editAssur (c. 2600 BCE – c. 1400 CE)

editAssur I dynasty (c. 2600 – c. 2025 BCE)

editTimeline

edit

Legend:

- Red denotes rulers of Ur

- Orange denotes rulers of Awan

- Gold denotes rulers of Kish

- Yellow denotes rulers of Hamazi

- Lime denotes rulers of Uruk

- Fern denotes rulers of Lagash

- Green denotes rulers of Umma

- Teal denotes rulers of Adab

- Blue denotes rulers of Mari

- Purple denotes rulers of Akshak

- Silver denotes rulers of Ebla

- Gray denotes rulers of Nagar

- Black denotes rulers of Assur