Steele's Greenville expedition took place from April 2 to 25, 1863, during the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces commanded by Major General Frederick Steele occupied Greenville, Mississippi, and operated in the surrounding area, to divert Confederate attention from a more important movement made in Louisiana by Major General John A. McClernand's corps. Minor skirmishing between the two sides occurred, particularly in the early stages of the expedition. Over 1,000 slaves were freed during the operation, and large quantities of supplies and animals were destroyed or removed from the area. Along with other operations, including Grierson's Raid, Steele's Greenville expedition distracted Confederate attention from McClernand's movement. Some historians have suggested that the Greenville expedition represented the Union war policy's shifting more towards expanding the war to Confederate social and economic structures and the Confederate homefront.

| Steele's Greenville expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War | |||||||

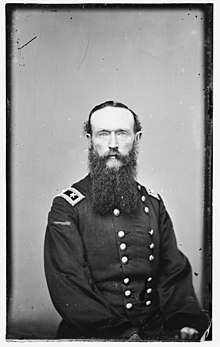

Major General Frederick Steele, who commanded the expedition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Frederick Steele |

Samuel W. Ferguson Stephen Dill Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,600 | 4,300 | ||||||

Background

editDuring early 1863, with the American Civil War ongoing, Union Army forces commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant were undertaking the Vicksburg campaign against the Confederate-held city of Vicksburg, Mississippi.[1] After having repeatedly failed to maneuver out of the surrounding swamps and onto high ground near Vicksburg, Grant decided between three options: an amphibious crossing of the Mississippi River and attack of the Confederate riverfront defenses; pulling back to Memphis, Tennessee, and then making an overland drive south to Vicksburg; and moving south of Vicksburg and then crossing the Mississippi River to operate against the city. The first option risked heavy casualties and the second could be misconstrued as a retreat by the civilian population and political authorities, so Grant chose the third option.[2] In late March, Grant ordered the XIII Corps, commanded by Major General John A. McClernand, to move down the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River and then prepare to cross the river at a point south of Vicksburg.[1]

As part of an attempt to distract the Confederate forces at Vicksburg, who were commanded by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, from McClernand's movement, Grant sent the division of Major General Frederick Steele to Greenville, Mississippi, which was roughly 70 miles (110 km) upriver from Vicksburg.[3] Steele's instructions were to land in the Mississippi Delta, advance to Greenville, and then operate in the Deer Creek area.[4] Major General William T. Sherman hoped that Steele might reach to where Deer Creek met Rolling Fork, which was the furthest Union penetration in the Steele's Bayou expedition.[5] Once there, the Union soldiers were to burn any baled cotton marked with "CSA", clear out any Confederate forces in the area, and burn abandoned plantations.[4] Steele was also instructed to warn civilians in the region that retaliation would be made for attacks on Union transports on the Mississippi.[6] About 5,600 soldiers of Steele's division were part of the expedition.[7] Lieutenant Colonel[8] Samuel W. Ferguson commanded the Confederate forces in the area.[9]

Expedition

editSteele's troops left the Young's Point, Louisiana, area late on April 2, heading upriver via steamboats. The soldiers in the ranks did not know their destination.[10] The next morning, the boats reached Smith's Landing;[11] Smith's was 20 miles (32 km) south of Greenville. Flooding rendered the terrain impassable in this area except on the levees,[12] and the Union soldiers learned that a large stash of cotton known to be in the area had already been burned. On either the next day[11] or April 5, the expedition reached Washington's Landing. While much of Steele's force remained the Washington's Landing area, detachments patrolled inward, learning that the path to Deer Creek was flooded.[4] After the soldiers returned to the transports, movement was made to Greenville that evening, and the Union troops disembarked the next morning at a point about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Greenville. Two regiments and the Union Navy tinclad steamer USS Prairie Bird were left at the landing point to guard it.[13]

Steele's pioneer force rebuilt a bridge near the plantation of Confederate officer Samuel G. French, and continued on inland.[8][a] The Union commander learned of the presence of Ferguson's Confederates on April 6. The Union officers pushed their troops hard, hoping to overtake and capture the Confederate force. Ferguson had known of the Union presence since not long after the landing, and he sent a messenger to Major General Carter L. Stevenson at Vicksburg, asking for instructions. Stevenson detached the brigade of Brigadier General Stephen Dill Lee to the area, with orders to secure Rolling Fork and then move up the Bogue Phalia stream and strike Steele's rear. Ferguson, in turn, withdrew his troops to the Thomas plantation, which was about 20 miles (32 km) north of Rolling Fork.[14] Additional reinforcements were positioned at Snyder's Bluff and along the Sunflower River, and some cottonclad gunboats were shifted southwards in response to the threat. In addition, Ferguson sent a task force to a bend on the Mississippi River with instructions to cut a levee near Black Bayou, with the intent of flooding the terrain in the area, particularly where a road in Steele's rear crossed a swamp.[15] Between the commands of Ferguson and Lee, the Confederates had about 4,300 soldiers.[16]

Ferguson prepared a delaying action. When, on the afternoon of April 7, Steele's column approached the Thomas plantation, Ferguson had Bledsoe's Missouri Battery and Sengstak's Alabama Battery open fire on them;[17] Ferguson's force was deployed in front of a canebrake.[15] Union forces had operated in this area before, during an expedition in February commanded by Brigadier General Stephen G. Burbridge, which had been intended to drive out Confederate troops that were harassing Union shipping.[18] Steele, in turn, deployed artillery and prepared to make an attack, but Ferguson withdrew,[19] 6 miles (9.7 km) south to the Willis plantation.[20] During the pursuit, Union troops stumbled across the body of a lynched African-American, who believing Ferguson's troops were Union forces, requested a gun with which to kill his master and expressed intent to rape white women.[21] Steele halted the pursuit on the morning on April 8, and his troops confiscated and destroyed goods found on the plantations in the area.[22] The presence of Lee's force became known to Steele, and he ordered a withdrawal, not wanting to fight both Confederate forces too far from Greenville. During the march back, the Union troops destroyed supplies and took horses, mules, and livestock from the surrounding area.[21] The Confederates pursued, and the Union troops skirmished with them on April 8, continuing on to the French plantation on the 9th.[23] Also on April 9, Pemberton learned from Stevenson that Union troops had landed at Greenville and the Lee had been sent to counter them; Pemberton ordered the transfer of 1,500 soldiers from Fort Pemberton to Rolling Fork to reinforce Lee and Ferguson.[24] The bridge the Union troops had built there collapsed on April 10 while a herd of cattle crossed it, leading to a delay that allowed Confederate troops to catch up to the Union column.[25] Union artillery fire held the Confederate troops at bay; after the Union forces crossed the bridge it was destroyed.[26] During the course of the expedition, Steele's troops had moved 43 miles (69 km) down Deer Creek.[25]

During the movements, many slaves flocked to the Union lines and followed the troops to gain their freedom.[27] Steele did not want this,[28] and encouraged them to remain on plantations; when the campaign began, he had been ordered to discourage slaves from fleeing to Union lines.[27] Unsure of what to do with the large number of followers, Steele sent a message to Sherman, but when Sherman did not respond, contacted Grant.[21] Grant advised Steele to encourage slaves to come to Union lines, and suggested that he should form regiments of United States Colored Troops out of male former slaves who volunteered for military services, much as Brigadier General Lorenzo Thomas had begun doing. About 500 African-Americans volunteered for the service, placed in new regiments to be led by white officers.[29]

April 13 saw Union troops make another sweep of the Greenville area. While Ferguson had withdrawn his troops, the Union soldiers found large quantities of supplies and cattle, which they brought back to camp.[30] Shortly thereafter, Lee's command withdrew from the area.[31] On April 20, Steele sent the 3rd and 31st Missouri Infantry Regiments to the Williams Bayou area; they returned on April 22 with quantities of mules, corn, and livestock.[32] While the Union troops had been ordered to avoid disturbing local families who were peaceful and remained at home, these orders were ignored. Many of the plantations in the area were burned,[33] and hard feelings against the Union forces grew among the local populace.[34] During the expedition Union forces took more than 1,000 animals, besides destroying 500,000 US bushels (18,000,000 L; 4,000,000 US dry gal; 3,900,000 imp gal) of corn.[35] Journalist Franc Wilkie accompanied the expedition and estimated the damages as at least $3 million.[36] The naval historian Myron J. Smith and the historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel say that around 1,000 slaves were freed,[35][37] while the historian Timothy B. Smith notes that estimates range to up to 2,000 or 3,000 slaves followed Steele's column back to Greenville.[38] On April 22, Grant instructed Steele to return from the Greenville area, but a shortage of transports prevented the Union soldiers from setting off until late on April 24. The next morning, Steele's forces returned to Young's Point.[32]

Aftermath

editIn the words of James H. Wilson, Steele's Greenville expedition made the Union army an implement of "agricultural disorganization and distress as well as of emancipation".[29] Both Sherman and Steele believed that Union troops had gone too far in behavior that affected civilians, rather than just targeting the Confederate war goals.[33] The historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel see the expedition as demonstrating a shift in the Union's war policy.[35] In an earlier communication, Henry Halleck had written to Grant that he believed that there would be "no peace but that which is forced by the sword". Grant accepted the policy of carrying the war to the social and economic structures of the Confederacy. In the future, in the words of Shea and Winschel, the Union army brought "the war home to [Confederate] civilians by enforcing emancipation and seizing or destroying all items of possible military value".[35] Besides ravaging an area important to the Confederate forces at Vicksburg of supplies, the Greenville expedition also drew Confederate attention away from McClernand's more important operations in Louisiana,[39] although other operations such as Grierson's Raid also played a role.[40]

In late April, Union forces crossed the Mississippi River south of Vicksburg and then moved inland.[41] The Union troops defeated a Confederate force in the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1, and on May 12 won another victory in the Battle of Raymond. After the action at Raymond, Grant decided to strike a Confederate force forming at Jackson, Mississippi, and then turn west towards Vicksburg.[42] Grant's troops won a small battle at Jackson on May 14, and then defeated Pemberton's army in the climactic Battle of Champion Hill on May 16.[43] After another Confederate defeat at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge on May 17, the Siege of Vicksburg began on May 18. When the city surrendered on July 4, it was a major defeat for the Confederacy.[44]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Bearss 1991, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Ballard 2004, p. 209.

- ^ a b Smith 2023, p. 290.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Bearss 1991, p. 110.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 334.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 108.

- ^ a b Bearss 1991, p. 109.

- ^ Grabau 2000, p. 63.

- ^ Bearss 1991, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Bearss 1991, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Smith 2023, p. 291.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 128.

- ^ Bearss 1991, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Smith 2023, pp. 166–167, 291.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 112.

- ^ a b c Ballard 2004, p. 210.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 292.

- ^ Bearss 1991, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Grabau 2000, p. 71.

- ^ a b Smith 2023, p. 293.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 116.

- ^ a b Miller 2019, p. 335.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 114.

- ^ a b Miller 2019, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 121.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 120.

- ^ a b Bearss 1991, p. 125.

- ^ a b Miller 2019, p. 336.

- ^ Ballard 2004, p. 211.

- ^ a b c d Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 92.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 299.

- ^ Smith 2023, p. 294.

- ^ Bearss 1991, p. 126.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 93.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 158, 160.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 164–167.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 170–173.

Sources

edit- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1991) [1986]. The Campaign for Vicksburg. Vol. II: Grant Strikes a Fatal Blow. Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Bookshop. ISBN 0-89029-313-9.

- Grabau, Warren (2000). Ninety-eight Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-068-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Smith, Myron J. (2012). The Fight for the Yazoo, August 1862–July 1864: Swamps, Forts and Fleets on Vicksburg's Northern Flank. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-6281-0.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2023). Bayou Battles for Vicksburg: The Swamp and River Expeditions, January 1–April 30, 1863. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3566-5.