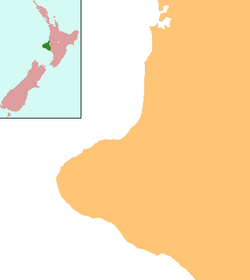

Parihaka is a community in the Taranaki region of New Zealand, located between Mount Taranaki and the Tasman Sea. In the 1870s and 1880s the settlement, then reputed to be the largest Māori village in New Zealand, became the centre of a major campaign of non-violent resistance to European occupation of confiscated land in the area. Armed soldiers were sent in and arrested the peaceful resistance leaders and many of the Maori residents, often holding them in jail for months without trials.

Parihaka | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 39°17′17.9″S 173°50′25.3″E / 39.288306°S 173.840361°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Taranaki |

| District | South Taranaki District |

| Population | |

| • Total | Fewer than 100 |

The village was founded about 1866 by Māori chiefs Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi on land seized by the government during the post-New Zealand Wars land confiscations of the 1860s. The population of the village grew to more than 2,000, attracting Māori who had been dispossessed of their land by confiscations[1] and impressing European visitors with its cleanliness and industry, and its extensive cultivations producing cash crops as well as food sufficient to feed its inhabitants.

When an influx of European settlers in Taranaki created a demand for farmland that outstripped the availability, the Grey government stepped up efforts to secure title to land it had confiscated but subsequently not taken up for settlement. From 1876 some Māori in Taranaki accepted "no fault" payments called takoha compensation, while some hapū, or sub-tribal groups, outside the confiscation zone took the government's payments to allow surveying and settlement.[2] Māori near Parihaka and the Waimate Plains rejected the payments, however, the government responded by drawing up plans to take the land by force.[3] In late 1878 the government began surveying the land and offering it for sale. Te Whiti and Tohu responded with a series of non-violent campaigns in which they first ploughed settlers' farmland and later erected fences across roadways to impress upon the government their right to occupy the confiscated land to which they believed they still had rights, given the government's failure to provide the reserves it had promised.[4] The campaigns sparked a series of arrests, resulting in more than 400 Māori being jailed in the South Island, where they remained without trial for as long as 16 months with the aid of a series of new repressive laws.[5]

As fears grew among white settlers that the resistance campaign was a prelude to renewed armed conflict,[6] the Hall government began planning a military assault at Parihaka to close it down.[7] Pressured by Native Minister John Bryce, the government finally acted in late October 1881 while the sympathetic Governor was out of the country. Led by Bryce, on horseback, 1,600 troops and cavalry entered the village at dawn on 5 November 1881.[8] The soldiers were greeted with hundreds of skipping and singing children offering them food. Te Whiti and Tohu were arrested and jailed for 16 months, 1,600 Parihaka inhabitants were expelled and dispersed throughout Taranaki without food or shelter and the remaining 600 residents were issued with government passes to control their movement. Soldiers looted and destroyed most of the buildings at Parihaka. Land that had been promised as reserves by a commission of inquiry into land confiscations was later seized and sold to cover the cost of crushing Te Whiti's resistance, while others were leased to European settlers, shutting Māori out of involvement in the decisions over land use.

In a major 1996 report, the Waitangi Tribunal claimed the events at Parihaka provided a graphic display of government antagonism to any show of Māori political independence. It noted: "A vibrant and productive Māori community was destroyed and total State control of all matters Māori, with full power over the Māori social order, was sought."[9] Historian Hazel Riseborough also believed the central issue motivating the invasion was mana: "Europeans were concerned about their superiority and dominance which, it seemed to them, could be assured only by destroying Te Whiti's mana. As long as he remained at Parihaka he constituted a threat to European supremacy in that he offered his people an alternative to the way of life the European sought to impose on them."[10]

The Parihaka International Peace Festival has been held annually there since 2006.

Marae

editThe local Parihaka marae now features the Rangikapuia, Te Niho, Toroānui and Mahikuare meeting houses.[11] It is a tribal meeting ground for the Taranaki hapū of Ngāti Haupoto and Ngāti Moeahu.[12]

In October 2020, the Government committed $457,693 from the Provincial Growth Fund to upgrade the Toroānui meeting house, creating 6 jobs.[13]

Settlement

editThe Parihaka settlement was founded about 1866, at the close of the Second Taranaki War and a year after almost all Māori land in Taranaki had been confiscated by the Government to punish "rebel" Māori. The settlement was established by a Māori chief and veteran of the Taranaki wars, Te Whiti o Rongomai, as a means of distancing themselves from European contact and association with warlike groups of Māori.[1] The pā was set in sight of Mt Taranaki and the sea, in a clearing ringed by low hills and beside a stream known as Waitotoroa (water of long blood). He was joined by a fellow chief, Tohu Kākahi and a close kinsman, Te Whetu. Later that year King Tāwhiao sent 12 "apostles" to live at Parihaka to strengthen the bonds between the Waikato and Taranaki Māori who were opposed to further land sales to the government or white settlers.[14] Within a year the settlement had grown to house more than 100 large thatched whare (houses) around two marae and by 1871 the population was reported to be 300. The Taranaki Medical Officer visited in 1871 and reported food in abundance, good cookhouses and an absence of disease. It was the cleanest, best-kept pā he had ever visited and its inhabitants "the finest race of men I have ever seen in New Zealand". Large meetings were held monthly, where Te Whiti warned of increasing levels of bribery and corruption to coerce Māori to sell their land, yet European visitors continued to be welcomed with dignity, courtesy and hospitality.[14]

By the end of the 1870s, it had a population of about 1500 and was being described as the most populous and prosperous Māori settlement in the country. It had its own police force, bakery and bank, used advanced agricultural machinery, and organised large teams who worked the coast and bush to harvest enough seafood and game to feed the thousands who came to the meetings. When journalists visited Parihaka in October 1881, a month before the brutal government raid that destroyed it, they found "square miles of potato, melon and cabbage fields around Parihaka; they stretched on every side, and acres and acres of the land show the results of great industry and care". The village was described as "an enormous native town of quiet and imposing character" with "regular streets of houses".[9]

Land pressures

editIn June 1868 hostilities resumed in Taranaki as a Ngāti Ruanui chief, Riwha Tītokowaru, launched a series of effective raids on settlers and government troops in an effort to block the occupation of Māori land. Te Whiti remained neutral during the nine-month-long war, neither helping nor hindering Tītokowaru.[1][14] When the war ended with Titokowaru's withdrawal in March 1869, Te Whiti declared the year to be te tau o te takahanga, "the year of the trampling underfoot", during which kings, queens, governors and governments would be trampled by Parihaka. He told a meeting there would be a new era of "fighting peace" with no surrender of land and no loss of independence. He also declared that because they had remained independent during the recent war, the confiscation of their land for being "rebellious British subjects" was unjust, invalid and void. Te Whiti's announcement at the meeting was reported to Premier Edward Stafford by Taranaki Land Purchase Officer Robert Reid Parris, who described him as "this young chief whose influence was strong in the province and with Tawhiao".[14][15]

In 1872 the Government acknowledged that although all Māori land in Taranaki had been confiscated, most of it had effectively fallen back into Māori ownership because so little had been settled by Europeans. As a result, the Government began buying back the land, including reserves and land given as compensation for wrongful confiscation.[16]

As Te Whiti continued to reject the offers, however, European anger towards Parihaka grew, fuelling calls for his "dangerous" movement to be suppressed. Newspapers and government agents that had earlier praised him as peaceful and amiable began describing him as a "fanatic" who gave "rambling", "unintelligible" and "blasphemous" speeches, producing a "baneful influence".[17]

By the mid-1870s, Taranaki was enjoying a rapid growth in immigration, with the founding of Inglewood and other farming towns, the creation of inland roads as far south as Stratford and a rail link from New Plymouth to Waitara. In mid-1878, as the provincial government pressured the Government for more land,[9] Colonial Treasurer John Ballance advocated the survey and sale by force of the Waimate Plains of South Taranaki. Cabinet members expected to raise £500,000 for government coffers from the sale.[17] In June Premier Sir George Grey and Native Minister John Sheehan held a big meeting at Waitara to dispense "gifts" including tinned fruits and jam, alcohol, clothing and perfume to Taranaki chiefs willing to sell. Neither Te Whiti nor Tawhiao attended, so Sheehan visited Parihaka and then the Waimate Plains, where he appeared to have persuaded Tītokowaru to permit land to be surveyed on the proviso that burial places, cultivations and fishing grounds would be respected and that fenced reserves would be created.[17]

Māori unease mounted as the surveying progressed, with little sign of the promised reserves. In February 1879 surveyors began cutting lines through cultivations and fences and trampling cash crops and also ran a road into Tītokowaru's own settlement. Māori retaliated by uprooting kilometres of survey pegs. Sheehan rode to Parihaka to justify the government's actions, but left after being verbally abused by Te Whiti. The next day, 24 March 1879, Te Whiti ordered his men to remove all the surveyors from the Waimate Plains. Though the surveyors would not leave of their own accord, the Māori quietly packed up each survey camp, loaded horses and drays and carted everything back across the Waingongoro River, between Manaia and Hāwera.[18]

Hectored by the settler press, which claimed extra farmland was needed and that "these lands should no longer be retained by turbulent, semi-barbarous people, too idle to put them to any use",[19] the Government on 26 March began advertising the sale of the first 16,000 acres (65 km2) of the Waimate Plains. On 24 April it announced the sale was postponed indefinitely. Sheehan determined to find out what had been promised to Māori and whether this was the cause of the interruption to the survey.[9][20] Still, however, the Government refused to confirm its promise of reserves.

Monthly meetings at Parihaka attracted Māori from all over New Zealand and let was set aside for each tribe to have its own marae, meeting house and cluster of whares throughout the village. As the population grew, so did the industriousness, with cultivations over a wider area and more than 100 bullocks, 10 horses and 44 carts in use.[17] Yet the gatherings continued to disturb settlers, who in late May called on Grey to boost Taranaki's armed constabulary, claiming they were "living in a condition of constant menace", in fear of their lives and "utterly at the mercy of the Natives". Māori in Ōpunake had begun ploughing up and fencing off settlers' fields, and threatening to take over the flour mill.[21] Residents at Hawera were convinced war would be commenced "at any moment"[22] and the Patea Mail urged a new "war of extermination" be waged against the Māori: "Justice demands these bloodthirsty fanatics should be returned to the dust ... the time has come, in our minds, when New Zealand must strike for freedom, and this means the death blow to the Māori race."[23]

First resistance: The Ploughmen

editOn 26 May 1879 those bullocks and horses began to be put to use ploughing long furrows through the grassland of white settler farmers – first at Ōakura and later throughout Taranaki, from Hāwera in the south to Pukearuhe in the north.[24] Most of the land had earlier been confiscated from Māori. Te Whiti insisted the ploughing was directed not against the settlers, but to force a declaration of policy from the Government, but farmers were incensed, threatening to shoot the ploughmen and their horses if they did not desist. Magistrates in Patea County advised Grey that Māori had 10 days to stop "molesting property" or they would be "shot down", while MP Major Harry Atkinson encouraged farmers to enrol as volunteers and militia soldiers.[25] He promised to upgrade their rifles and was reported in the Taranaki Herald as saying "he hoped if war did come, the natives would be exterminated".[26] At Hawera a group of 100 armed vigilantes confronted ploughmen, but were talked out of violence by those they had come to threaten.

On 29 June the armed constabulary began arresting the ploughmen. Large squads pounced on the ploughing parties, who offered no resistance. Dozens a day were arrested, but their places were immediately taken by others who had travelled from as far away as Waikanae. Te Whiti directed that those of the greatest mana, or prestige, should be the first to put their hands to the ploughshares, so among the first arrested were the prominent figures Tītokowaru, Te Iki and Matakatea.[9] As Taranaki jails became full, ploughmen were sent to the Mt Cook barracks in Wellington. By August almost 200 prisoners had been taken.[27][28] By then, however, the protest action seemed to be having some success, with Sheehan, the Native Minister, telling Parliament on 23 July: "I was not aware ...what the exact position of those lands on the west coast was. It has only been made clear to us by the interruption of the surveys. It turns out that from the White Cliffs to Waitōtara the whole country is strewn with unfulfilled promises."[29] A former Native Minister, Dr Daniel Pollen, also warned of the consequences of firmer government action against the Parihaka ploughmen: "I warn my honourable friend that there are behind Te Whiti not two hundred men, but a great many times two hundred men." All the prisons of New Zealand would not be big enough to hold them, he warned.

On 10 August leading pro-government chiefs issued a proclamation to all tribes of New Zealand calling on the government to halt surveys of disputed lands and on Māori to end their action in claiming those lands. The proclamation also proposed testing the legality of the confiscations in the Supreme Court. Te Whiti agreed to a truce and by the end of the month the ploughing ended.

Imprisonment

editThe first 40 ploughmen were brought before court in July, charged with malicious injury to property, forcible entry and riot. They were sentenced to two months' hard labour and ordered to either pay a £600 surety for 12 months' good behaviour following their release or—if they could not raise the money—be imprisoned in Dunedin jail for 12 months.[30] The Government declined to lay charges against any of the remaining 180 protesters, but also refused to release them. Colonial Minister and Defence Minister Colonel George S. Whitmore, who had led colonial forces against Titokowaru in 1868–69, admitted it was necessary to bend the law to keep the protesters incarcerated, fearing they would be released by the Supreme Court if they went on trial.[31] The Grey government was on the point of collapse following a series of no-confidence motions, but to provide a legal backing for its move rushed the Maori Prisoners' Trial Bill through both Houses on the final day of its session in office, Whitmore justifying the haste by claiming the "actual safety of the country and of the lives and property of its loyal subjects" was at stake. No translation of the legislation was provided, despite protests by Māori MPs.[32] The new law provided that the detainees were to be brought to trial anywhere in the colony on a date nominated by the Governor within 30 days of the opening of the next session of parliament.

The new Hall Government was formed in October 1879 and promptly introduced more legislation to deal with the "Parihaka question". On 19 December the Confiscated Land Inquiry and Maori Prisoners' Trials Act was passed into law. The Act provided for an "inquiry into alleged grievances of Aboriginal Natives in relation to certain lands taken by the Crown"—the confiscated territory in Taranaki—and it also enabled the Governor to postpone the trials of the Māori prisoners, who had been scheduled to appear at the Supreme Court in Wellington in late December. John Bryce, the new Native Minister, told Parliament he did not attach much importance to the idea of inquiring into Māori grievances; Sheehan, his predecessor, admitted there were many unfulfilled promises and that the west coast people had enough grievances to justify what they had done, but said it was in their interests to suffer "mild confinement" until the government had settled the question.[33]

A new trial date was set—5 April 1880 in Wellington—but in January 1880 the government quietly moved all the prisoners to the South Island, incarcerating them in jails in Dunedin, Hokitika, Lyttelton and Ripapa Island in Canterbury.[9] The move prompted Hōne Tāwhai, the member for Northern Maori, to remark: "I cannot help thinking that they must have been taken there in order that they might be got rid of, and that they might perish there."[33][34] In late March the trial date was put back to 5 July; in late June it was moved again to 26 July.[33]

Many of the prisoners had already been in jail for 13 months when, on 14 July 1880 Bryce introduced the Maori Prisoners' Bill designed to postpone their trial indefinitely. Bryce, who prided himself on plain talk, told Parliament it was "a farce to talk of trying these prisoners for the offences for which they were charged ... if they had been convicted in all probability they would not have got more than 24 hours' imprisonment. In the Bill we drop that provision in regard to the trial altogether."[34] The new legislation declared that all those in jail were now deemed to have been lawfully arrested and to be in lawful custody and decreed that "no Court, Judge, Justices of the Peace or other person shall during the continuance of this Act discharge, bail or liberate the said Natives".[35]

Sheehan, meanwhile, claimed Te Whiti's people were wavering and would soon break up, while Bryce declared the end game was within sight: "I fully expect, in the course of next summer, to see hundreds of settlers on these plains."[34]

West Coast Commission

editIn January 1880, a month after the government provided for an inquiry into grievances over west coast land confiscations and allegations of broken promises, Governor Sir Hercules Robinson appointed MP Hone Tawhai, former premier Sir William Fox and pastoralist and former cabinet minister Sir Francis Dillon Bell as members of the West Coast Commission, with Fox as its chairman.[9] Tawhai resigned before hearings began, claiming his fellow commissioners were not impartial and had been the "very men who had created the trouble on the West Coast". Fox and Bell had both served as Native Minister, owned vast areas of land and supported confiscation.[9] Tawhai may also have been stung by Te Whiti's description of the commission as "two pākehā and a dog".[34]

Hearings began at Oeo, South Taranaki, in February, but were immediately boycotted by Te Whiti's followers when the commission refused to travel to Parihaka to hold discussions.[2][9] Historian Dick Scott has claimed Fox, who had already expressed in writing his wish that the Waimate Plains be sold and settled, was appointed chairman of the commission on the proviso that he support the government's land policies in the area and secure central Taranaki for white settlement. Correspondence to Premier John Hall shows that Fox thought it futile to give a hearing to "every Native who thinks he has a grievance" and was keen to ensure commission hearings did not delay road-building works in the Waimate Plains that could be carried out in summer.[36]

Fox insisted that no survey of land around Parihaka should take place until the commission had made a report. Bryce agreed that central Taranaki would not be entered, apart from the completion of necessary road repairs. In April, however, he found just such a necessity, directing that 550 armed soldiers–mostly unemployed men newly recruited with the promise of free land[37]–would begin "repairing" a new road that would lead directly to Parihaka.[9] His force marched from Oeo to set up camp near Parihaka. A stockade and camp were established at Rahotu, a redoubt and blockhouse at Pungarehu and an armed camp at Waikino to the north. The land around Parihaka began to be surveyed and work began, from both northern and southern approaches, on a coast road between New Plymouth and Hawera. Apart from offering food to the soldiers, Māori continued their daily life as if the surveyors did not exist. In its 1996 report on Taranaki land confiscations, the Waitangi Tribunal noted that Bryce was a Taranaki war veteran who "clearly retained his relish of warfare ... on his own admission, he had always desired a march on Parihaka in order to destroy it." The tribunal claimed his later actions were "so provocative that, in our view, he was also endeavouring to recreate hostilities."[9]

In their first interim report, released in March 1880, Fox and Bell acknowledged the puzzle of why the land had been confiscated when its owners had never taken up arms against the government, although they had made plain from the outset that they would not allow submissions on the validity of the confiscations.[37][38] They recommended the delineation of a "broad continuous belt of reserve" of about 25,000 acres (100 km2) on the Waimate Plains and a further reserve of 20,000 to 25,000 acres for the Parihaka people—"so long as they live there in peace".[38] A second interim report was released on 14 July, followed by the third and final report on 5 August. This last report expressed the commissioners' wish "to do justice to the Natives" and also to continue "English settlement of the country". It urged the government to fulfill the promises made by successive ministries, then recommended that the Crown retain the section of the Parihaka block between the new road and the coast (the area of best arable land) but return the rest of the Parihaka block to Te Whiti and his people. The commissioners also made it clear that no act of Te Whiti's between the ploughing in 1879 and the fencing in 1880 could "fairly be called hostile".[38][39] Bryce, who had strongly opposed the work of the commissioners and resented their influence, was dismissive of their report in his parliamentary address on it and gave no suggestion he would implement the recommendations.[40]

Further resistance: The Fencers

editIn June 1880, meanwhile, the road reached Parihaka and on Bryce's instruction, the Armed Constabulary broke fences around the large Parihaka cultivations, exposing their cash crops to wandering stock, crossed cultivations and looted Māori property.[9][41] The New Zealand Herald reported the next Māori tactic as surveying began there: "Our position is a very unhappy one. We assign reserves for natives ... indicate (sites for) European settlement. The natives reply by building houses, fencing, planting and occupying our camping grounds." As soldiers and surveyors cut down fences and marked out road lines across fields of crops, Māori just as quickly rebuilt the fences across the roads. When soldiers pulled them down, Māori put them back up again, refusing to answer questions about who was directing them. When Te Whetu threatened in July 1880 to cut down telegraph poles, he was arrested with eight other men and taken to New Plymouth. For the Government, it was the beginning of a new campaign in which fencers were arrested, often being dragged off by force as they continued work on building fences. According to the Waitangi Tribunal, the arrests were invalid: the land was not Crown land and therefore it was the army, not Māori, who were trespassing. Nor were the actions of the Māori fencers a criminal activity.[9] Yet the number of arrests grew daily and Māori began to travel from other parts of the country, including Waikato and Wairarapa, to provide more manpower. In one incident 300 fencers arrived at the roadline near Pungarehu, dug up the road, sowed it in wheat and constructed a fence, with a newspaper reporting: "They looked like an immense swarm of bees or an army of locusts, moving with a steady and uninterrupted movement across the face of the earth. As each portion was finished they set up a shout and a song of derision."[42]

The Government responded with the Maori Prisoners' Detention Act (enacted 6 August, the day after the West Commission released its final report) to keep all the prisoners in detention, and then, on 1 September 1880, the even harsher West Coast Settlement (North Island) Act, which widened the powers of arrest and provided for two years' jail with hard labour–with the offender released only if he paid a surety nominated by the court. Arrests could be made for anyone even suspected of "endangering the peace" by digging, ploughing or disturbing the surface of the land, or erecting or dismantling a fence. Governor Robinson regarded the legislation as necessary in the Māoris' own interests and said it was "devised for the purpose of averting another Maori war", but Grey said the law "amounted to a general warrant for the apprehension of all persons ... for offences which were not named at all – in fact they might be arrested for no offence."[42][43]

By September about 150 fencers had been detained and sent to South Island jails[43] and the adult male ranks at Parihaka were so depleted, the constabulary were often manhandling young boys and old men, whose fences were often only symbolic, consisting of sticks and branches.[44] When a group of 59 Māori appeared in the District Court in New Plymouth on 23 September for trial on charges of having unlawfully obstructed the free passage of a thoroughfare, a jury of 12 settlers deliberated for 45 minutes before returning to say they could not agree on a verdict. Judge Shaw told the jurors that if they convicted the accused, he might choose to sentence them "to only an hour's imprisonment" and bind them over to keep the peace "for only a nominal time". He told the jurors that if they did not produce a verdict within an hour he would lock them up for the night. They deliberated for just minutes before returning with a guilty verdict. The judge immediately sentenced the fencers to two years' imprisonment with hard labour at Lyttelton jail, plus a requirement for each to find a £50 surety to keep the peace for six months.[43]

From that date there were no more arrests.[43] The cost of the operation had grown too much: while the land being taken was estimated at £750,000, the costs of the operation in South Taranaki had already exceeded £1 million. The bloody clashes between armed soldiers and unarmed Māori building fences on their own land, as well as the increasing numbers of deaths in custody in the freezing South Island jails, were already attracting the attention of the British House of Commons and newspapers in Europe. In New Zealand, however, the plight of more than 400 political prisoners – equally divided between ploughmen and fencers – attracted scant press coverage.[28] Only when about 100 prisoners were finally released from South Island jails in November 1880 did newspapers begin to report on the deaths in jail, the terms of solitary confinement and tales of gross overcrowding in cells. Reporters noted that some prisoners at Lyttelton jail were terminally ill, while others were "in a very critical state and scarcely able to walk".[45]

Bryce unsuccessfully sought to impose conditions on the men as they were released, including their acceptance of reserves.[9] The remaining 300 prisoners were released in the first six months of 1881. As they returned to Taranaki they learned that the Government had decided to survey and sell four-fifths of the Waimate Plains and 31,000 acres (130 km2), or more than half, of the 56,000 acres (230 km2) Parihaka block. Parihaka, in fact, was to be carved into three sections, with the seaward and inland on the village marked for pākehā settlement and the Māori left with a strip in between.[45] Bryce vowed that "English homesteads would be established at the very doors of (Te Whiti's) house".[9] In January 1881 Bryce resigned as Native Minister, angry at the lack of government support for his plans to invade Parihaka and close the settlement.[46]

The sell-off of central Taranaki continued, however, and in June 1881, with most of the Waimate Plains auctioned off, the Commissioner of Crown Lands sold 753 acres (3.05 km2) of the Parihaka block for just over £2.10.0 an acre, with still no reserves marked out. Despite the sale, Māori at Parihaka continued to clear, fence and cultivate the land, regardless of whether it had been surveyed and sold, with their persistence leading to the use of more than 200 Armed Constabulary to pull down fences, which in turn prompted a pursuit by Māori armed with sticks.[47] By September newspapers were reporting that "certain quarters" were persisting in working up a scare campaign, suggesting Te Whiti was fortifying Parihaka and preparing to invade New Plymouth, while the Taranaki Herald reported that the settlement was "in a horribly filthy state" and its inhabitants "in a deplorable condition"–a stark contrast to the situation a Wellington doctor discovered when he visited, writing that the place was "singularly clean ... regularly swept ... drainage is excellent".[48]

Invasion

editThe British Government, already uneasy about growing racial tensions in New Zealand, had in late 1880 dispatched a new governor, Sir Arthur Gordon, to review matters and report to them. Gordon was more sympathetic to the Māori[9] and had already been dismissed as a "gospel-grinding nigger lover" by retired Native Land Court judge Frederick Maning and a man of "wild democratic theories" by Premier Hall.[49] In mid-September 1881 Gordon sailed for Fiji, leaving Chief Justice Sir James Prendergast as acting Governor. In his absence, and with an election looming, Hall's ministry completed its plans to invade Parihaka. Bryce's replacement as Native Minister, Canterbury farmer William Rolleston, secured two votes worth a total of £184,000 for contingency defence against Taranaki Māori and the government significantly boosted the number of Armed Constabulary on the west coast. On 8 October Rolleston visited Parihaka to urge Te Whiti to submit to the Government's wishes. If he refused and war ensued, Rolleston explained, "the blame will not rest with me and the government. It will rest with you."[50][51]

When news of the Hall government's plans reached Gordon, he terminated his Fiji visit and hurried back to New Zealand. At 8pm on 19 October, two hours before the Governor returned to Wellington, however, Hall convened an emergency meeting of his Executive Council and Prendergast issued a proclamation berating Te Whiti and his people for their "threatening attitude", their rebellious speech and their resistance of the armed constabulary. It urged the people of Parihaka to leave Te Whiti and for the visitors to return home. It gave them 14 days to accept the "large and ample" reserves on the conditions attached to them by the government and willingly submit to the law of the Queen or the lands would forever pass away from them and they alone would be responsible for this and "for the great evil which must fall on them." "As usual," observed historian Hazel Riseborough, "it was a question of mana." The proclamation was signed by Rolleston late on 19 October—his last act as minister before Bryce was returned to Cabinet and just two hours before Gordon arrived back in New Zealand. The Governor, though angry at the issuing of the Proclamation, acknowledged it would be supported "by nine-tenths of the white population of the colony" and allowed it to stand.[52]

Tensions climbed among Europeans in Taranaki. Although it had been more than 12 years since the last military action against Māori in Taranaki, and despite the lack of any threat of violence by the inhabitants of Parihaka, Major Charles Stapp, commander of the Taranaki Volunteers, declared that every man in the province between 17 and 55 years was now on active service in the militia. A government Gazette announcement called up 33 units of volunteers from Nelson to Thames.[53] At the end of October the forces–1,074 Armed Constabulary, almost 1,000 volunteers from around New Zealand and up to 600 Taranaki volunteers, together outnumbering Parihaka adult males by four to one–gathered near Parihaka, the volunteers at Rahotu and the Armed Constabulary at Pungarehu, and began drills and target practice. Bryce rode in their midst daily.

On 1 November Te Whiti prepared his people with a speech in which he warned: "The ark by which we are to be saved today is stout-heartedness, and flight is death ... There is nothing about fighting today, but the glorification of God and peace on the land ... Let us wait for the end; there is nothing else for us. Let us abide calmly upon the land." He warned against armed defence: "If any man thinks of his gun or his horse and goes to fetch it, he will die by it."[53] The settler press continued to denounce the Parihaka meetings as "schools of fanaticism and sedition" and said Te Whiti and Tohu needed to be "taught the lesson of submission and obedience".[54]

Shortly after 5am on 5 November, long columns emerged from the two main camps to converge on Parihaka, encircling the village. Each man carried two days' rations, the troops were equipped with artillery and a six-pound Armstrong gun was mounted on a nearby hill and trained on Parihaka.[9] At 7am a forward unit advanced on the main entrance to the village to find their path blocked by 200 young children, standing in lines. Behind them were groups of older girls skipping in unison. Colonel William Bazire Messenger, who had been called from his Pungarehu farm to command a detachment of 120 Armed Constabulary for the invasion, later recalled:

Their attitude of passive resistance and patient obedience to Te Whiti's orders was extraordinary. There was a line of children across the entrance to the big village, a kind of singing class directed by an old man with a stick. The children sat there unmoving, droning away, and even when a mounted officer galloped up and pulled his horse up so short that the dirt from its forefeet spattered the children they still went on chanting, perfectly oblivious, apparently, to the pakeha, and the old man calmly continued his monotonous drone. I was the first to enter the Maori town with my company. I found my only obstacle was the youthful feminine element. There were skipping-parties of girls on the road. When I came to the first set of girls I asked them to move, but they took no notice. I took hold of one end of the skipping-rope, and the girl at the other end pulled it away so quickly that it burnt my hands. At last, to make a way for my men, I tackled one of the rope-holders. She was a fat, substantial young woman, and it was all I could do to lift her up and carry her to one side of road. She made not the slightest resistance, but I was glad to drop the buxom wench. My men were all grinning at the spectacle of their captain carrying the big girl off. I marched them in at once through the gap and we were in the village. There were six hundred women and children there, and our reception was perfectly peaceful.[55]

When the advance party reached the marae at the centre of the village, they found 2500 Māori sitting together. They had been waiting since midnight. At 8am Bryce, who had ordered a press blackout and banned reporters from the scene,[56] arrived, riding on a white charger. Two hours later he demanded a reply to the proclamation of 19 October. When his demand was met with silence, he ordered the Riot Act to be read, warning that "persons unlawfully, riotously, and tumultuously assembled together, to the disturbance of the public peace"[57] had one hour to disperse or receive a jail sentence of hard labour for life. Before the hour was up, a bugle was sounded and troops marched into the village.

Bryce then ordered the arrest of Te Whiti, Tohu and Hiroki, a Waikato Māori who had sought refuge at Parihaka after killing a cook travelling with a survey party in south Taranaki in late 1878.[58] As Te Whiti walked through his people, he told them: "We look for peace and we find war."[59] At the marae the crowd remained sitting quietly until evening, when they moved to their houses.

Two days later constabulary officers, still on edge because of rumours that Titokowaru had summoned armed 500 reinforcements,[60] began ransacking houses in the village in search of weapons. They turned up 200 guns, mostly fowling pieces. Colonel Messenger told Cowan there was "a good deal of looting – in fact robbery" of greenstone and other treasures.[55] "Rapes [were] committed by Crown troops in the aftermath of the invasion".[61] Bryce ordered members of all tribes who had migrated to Parihaka to return to their previous homes. When none moved, they were warned the Armstrong gun on Fort Rolleston, the hill overlooking the village, would be fired at them. The threat was not carried out, but soldiers amused themselves by aiming their rifles at the crowd.

The next day the constabulary began raiding other central Taranaki Māori settlements in search of arms, and within days the raids, accompanied by destruction and looting, had spread to Waitara. On 11 November, 26 Whanganui Māori were arrested and Bryce, frustrated in his attempt to identify those from outside central Taranaki, telegraphed Hall to advise he intended destroying every whare in the village. He told Hall: "Consider, here are 2000 people sitting still, absolutely declining to give me any indication of where they belong to; they will sit still where they are and do nothing else."

Each day brought dozens of arrests, and from 15 November officers began destroying whare that were either empty or housing only women, assuming they were the homes of the evicted Wanganui men. When still Wanganui women could not be conclusively identified, a Māori informer was brought in to identify them. North Taranaki Māori, including children, were then separated–"like drafting sheep," one newspaper reported–and then marched under guard to Waitara. To starve out the remainder, soldiers destroyed all surrounding crops, wiping out 45 acres (180,000 m2) of potatoes, taro and tobacco, then began repeating the measure across the countryside.[9] By 18 November, as many as 400 a day were being evicted and, by the 20th, 1443 had been ejected, their houses destroyed to discourage their return.[59] Te Whiti's meeting house was destroyed and its smashed timbers scattered across the marae in an attempt to desecrate the ground.

On 22 November the last group of 150 prisoners were marched out, bringing to a total of 1600 people ejected. Six hundred were issued with official passes and allowed to remain. Those without a pass were prohibited from entry. Further public meetings were banned. Scott noted:

The largest, most prosperous town in Māori history had been reduced to ruins in a little under three weeks, not long by ordinary time, but the first gunpoint ultimatum had given the people one hour to disperse. And then a day of threats had extended to 18 days ...[62]

By December it was reported that many dispersed Māori faced starvation. Bryce offered them work, but it was the ultimate humiliation—roadmaking and fencing for the subdivision of their land. The government then decreed that 5,000 acres (20 km2) of land set aside as Parihaka reserves would be withheld as "an indemnity for the loss sustained by the government in suppressing the ... Parihaka sedition".[9] As with the land confiscations of the mid-1860s, Māori were effectively forced to pay the government for the cost of the military invasion of their land.

Trial of Te Whiti, Tohu and Titokowaru

editTe Whiti and Tohu appeared before a magistrate and eight justices of the peace in the New Plymouth courtroom on 12 November 1881. Te Whiti was described in court as "a wicked, malicious, seditious and evil-disposed person" who had sought "to prevent by force and arms the execution of the laws of the realm". At the close of his four-day trial Te Whiti declared: "It is not my wish that evil should come to the two races. My wish is for the whole of us to live peaceably and happy on the land." The magistrate committed both men to jail in New Plymouth until further notice. Six months later they were moved to the South Island, where they were frequently taken from jail to be escorted around the factories, churches and public buildings.[63]

Titokowaru, who had been put in solitary confinement at the Pungarehu constabulary camp, went on a brief hunger strike in protest at his treatment. On 25 November he was charged with threatening to burn a hotel at Manaia in October and using insulting language to troops at Parihaka in November. Three weeks later, while still in jail, a third charge of being unlawfully obstructive–for sitting on the marae at Parihaka–was laid against him. The magistrates ordered him to find to sureties of £500 each to keep the peace for 12 months and to be kept in the New Plymouth jail in the meantime. He remained in jail until July 1882 when bail was posted for him.[64]

In May 1882 the government introduced new legislation, the West Coast Peace Preservation Bill, which decreed that Te Whiti and Tohu were not to be tried, but would be jailed indefinitely. If released, they could be rearrested without charge at any time.[65] Bryce explained that the law was necessary to protect the people of Taranaki and because he feared the two chiefs might be acquitted by a jury or, if they were convicted, receive a lenient sentence.[66] The legislation, signed into law on 1 July, was followed by the Indemnity Act, which indemnified those who, in preserving the peace on the west coast, may have adopted measures "in excess of legal powers".[65]

Still in jail at the time, however, Te Whiti was visited by one of Bryce's staff, who told him that if he agreed to cease assembling his people he could return to Taranaki, where he would receive a government income and land for himself. Te Whiti refused. The offer was repeated, and rejected, two weeks later. The prisoners were transferred to Nelson, where they received a third offer in August. They were finally released in March 1883—a month after a general amnesty was proclaimed for all Māori[67]—and returned to Parihaka, still under threat of arrest under the powers of the West Coast Peace Preservation Act, renewed in August 1883. His remaining land was still shrinking: on 1 January 1883 the reserves granted to Māori by the West Coast Commission—many of which were described by Fox as "extremely rugged country, broken by deep and wide gullies and covered by extremely heavy forest"—were vested in the Public Trust for 30-year lease to European settlers at market rental, prompting Te Whiti to refuse to sign documents and refuse to collect the rental income of £7000 a year.[68][69]

Campaign renewed

editArmed constabulary remained stationed at Parihaka, enforcing the pass laws and the ban on public meetings, yet rebuilding began. In August 1884 Te Whiti and Tohu began a new campaign to publicise the loss of their land, embarking on large protest marches across Taranaki, as far south as Patea and north to White Cliffs. In July 1886 the campaign changed direction as Māori began entering pākehā farms to occupy the land and erect thatched huts. Titokowaru and eight other Māori were arrested and on 20 July armed constables launched a dawn raid on Parihaka to arrest Te Whiti. Ten weeks later they faced a Supreme Court trial in Wellington. Te Whiti was jailed for three months and fined £100 for being an accessory to forcible entry, riot and malicious injury to property; the others were jailed for a month and fined £20. In late 1889 Te Whiti was arrested again over a disputed £203 debt and sentenced to three months' hard labour.[31]

Parihaka restored

editIn 1889 work began on a meeting house and Te Raukura, a large Victorian mansion containing dining rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, a bakery and council chambers for Te Whiti and his rūnanga (council). In 1895 Parihaka received a state visit by the Minister for Labour, William Pember Reeves and, two months later, Premier Richard Seddon, who engaged in a tense exchange with Te Whiti over past injustices. Seddon, speaking to Patea settlers days later, boasted over the increased rate of land acquisition by the Government and told them Parihaka had encouraged Māori to lead "lazy and dissolute" lives. He vowed that the state would destroy "this communism that now existed among them".[31]

Tohu died on 4 February 1907 and Te Whiti died nine months later, on 18 November.

Their followers have continued to observe monthly dusk-to-dusk Te Whiti and Tohu days at Parihaka ever since. That for Te Whiti is held in the meeting houses Te Niho o te Ati Awa and Te Paepae, and for Tohu in Te Rangi Kāpuia. Although nominally on the 17th and 18th of each month, they are actually held on the 18th and 19th. (One reason offered for this is to compensate for the day lost during the Battle of Jericho.) In the same way, the anniversary of the sacking, 5 November, is observed on 6 November.

Te Raukura was destroyed by fire in 1960. Only its foundations remain.

Apology and redress

editSeveral Taranaki tribes were affected by the Parihaka incident. Between 2001 and 2006, the New Zealand government provided redress and a formal apology to four of those tribes, Ngati Ruanui, Ngati Tama, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and Ngati Mutunga, for a range of historical issues including Parihaka. Tens of millions of New Zealand dollars were provided as redress to the tribes in recognition of their losses at Parihaka and the confiscations. Most of the confiscated land is now privately owned, and worth considerably more.[citation needed]

In June 2017, the Crown formally apologised to the community. Treaty Negotiations Minister Chris Finlayson delivered the apology on behalf of the Crown, and noted it had been a long time coming. He said past events at Parihaka were "among the most shameful in the history of our land". He also said the Crown regretted its actions, which had left it with a legacy of shame.[70]

Although there were more violent incidents during the New Zealand Wars, the memory of Parihaka is still invoked as a symbol of colonial aggression against the Māori people.[citation needed]

References in popular culture

editThe story of Parihaka lay largely forgotten by non-Māori New Zealanders, until the publication of The Parihaka Story by Dick Scott in 1954. It was revised and enlarged as Ask That Mountain[71] in 1975.

New Zealand composer Anthony Ritchie composed an orchestral work Remember Parihaka (Op. 61) in 1964, inspired by Dick Scott's 1954 book.[72]

A sardonic "song-play" about Māori land issues including Parihaka, Songs for the Judges, with words by Mervyn Thompson and music by William Dart, was performed in Auckland in February 1980 and toured in 1981. Two of the songs, Gather up the Earth and On that Day, are based on sayings of Te Whiti. It was issued as an LP (SLD-69) by Kiwi/Pacific Records in 1982.

A play about Parihaka by Harry Dansey called Te Raukura was first performed in Auckland and then, in a cut-down version for school-age performers, in the Hutt Valley and at Parihaka in 1981.

In 1989 musicians Tim Finn and Herbs released the song Parihaka about the incident.

In 2011, New Zealand author Witi Ihimaera published a novel called The Parihaka Woman which provides a fictional story about a woman named Erenora from Parihaka but also provides much historical fact on the subject.[73]

A song released in 2022 by Don McGlashan, John Bryce, compares how well-taught and remembered the events of the Gunpowder Plot of 5 November 1605 are compared to the events at Parihaka on 5 November 1881. The former continue to inspire annual Guy Fawkes Night celebrations in New Zealand, but McGlashan's chorus suggests, "let's put a new guy on the bonfire...Light up John Bryce on the 5th of November / Make it Parihaka Day".[74]

References

edit- ^ a b c Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Belgrave, Michael (2005). Historical Frictions: Maori Claims and Reinvented Histories. Auckland: Auckland University Press. pp. 252, 254. ISBN 1-86940-320-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 50, 108. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 2. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 79, 84. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand, Penguin, 2003, chapter 15

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 109. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 111–117. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, chapter 8.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 212. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ "Māori Maps". maorimaps.com. Te Potiki National Trust.

- ^ "Te Kāhui Māngai directory". tkm.govt.nz. Te Puni Kōkiri.

- ^ "Marae Announcements" (Excel). growregions.govt.nz. Provincial Growth Fund. 9 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 31–38. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 232, footnote 51. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, chapter 7.

- ^ a b c d Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 50, 54. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 53–55. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ The Taranaki News, 19 April 1879, as cited by Riseborough, pg 65.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 58, 62. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ The Patea Mail, 7 June 1879

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 69–70, 74. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ The Patea Mail, 7 June 1879, as cited by Riseborough, pg 73.

- ^ James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume II, 1922, page 478.

- ^ Brian L. Kieran, The New Zealand Cross: The rarest bravery award in the world. AuthorHouseUK (2016)]

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 56. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 80, 82. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Scott's book refers to a total of about 400 Māori were arrested in the ploughing and fencing campaigns. The Waitangi Tribunal, at section 8.13 of its Taranaki report, claims more than 420 ploughmen were imprisoned by the end of 1879 and that 216 fencers were arrested in 1880, making a total of more than 636 arrests over the course of the two campaigns.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 61. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 76. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b c Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b c Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 87–88, 91, 104–105. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b c d Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 61–65. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Richmond-Atkinson papers, G. H. Scholefield (ed.), (1960), as cited by Scott, pages 66–7.

- ^ a b Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 71, 72. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ a b c Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 95, 98, 111. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Reports of the West Coast Royal Commission, 1880, Page liii, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, National Library of New Zealand website.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 113, 116–117. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 103. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 77, 78. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ a b c d Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 112, 114–115. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 80. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ a b Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 85, 86. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 130–133. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 96. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 81. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 99. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 144, 147, 152, 241 footnote 84. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 154–159. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 103, 106. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 162. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume II, pages 517-8, 1922.

- ^ His order, according to Scott, was ignored by several reporters who arrived at Parihaka before dawn to warn Te Whiti and then watched the day's events from concealed positions.

- ^ The Riot Act of 1714

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 166–169. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. pp. 120–121, 127. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Te Ture Haeata ki Parihaka 2019 [Parihaka Reconciliation Act 2019] (60, Schedule 1). New Zealand Parliament. 30 October 2019.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 130. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 186. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 176, 196. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ a b Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 183, 186. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 139. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 198, 199. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. p. 147. ISBN 0-86863-375-5.

- ^ Riseborough, Hazel (1989). Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1878-1884. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. pp. 205, 209. ISBN 0-04-614010-7.

- ^ "Crown apologises to Parihaka for past horrors". Stuff. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ^ Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. ISBN 0-7900-0190-X.

- ^ Composer's information page.

- ^ "The Parihaka Woman by Witi Ihimaera". Random House Books. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ McKinlay, Tom (28 February 2022). "Pop and Parihaka". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

External links

edit- parihaka.com

- Parihaka - Past, Present, and Future

- Winder, Virginia (27 May 2003). "The Plunder of Parihaka". Puke Ariki.

- Legacy of Parihaka

- New Zealand in History: Parihaka

- Summary of the Ngati Mutunga Treaty settlement (pdf, 4 pages)

- Parihaka and the Gift of Non Violent Resistance

- Waitangi Tribunal Report into Taranaki Claims

- Parihaka International Peace Festival Gallery

- Parihaka Music Video by Tim Finn and Herbs, 1989, New Zealand Film Archive