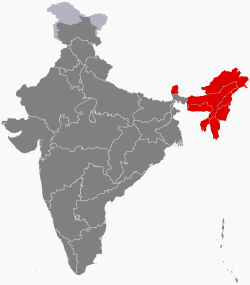

Northeast India, officially the North Eastern Region (NER), is the easternmost region of India representing both a geographic and political administrative division of the country.[18] It comprises eight states—Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura (commonly known as the "Seven Sisters"), and the "brother" state of Sikkim.[19]

Northeast India | |

|---|---|

| North Eastern Region (NER) | |

From top, left to right: Sela Pass, Loktak Lake, Kolodyne castle, Unakoti stone relief, Kaziranga National Park, Umngot River, Dzukou Valley, Kangchenjunga | |

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 26°N 91°E / 26°N 91°E | |

| Country | |

| States | |

| Largest city | Guwahati |

| Major cities (2011 Census of India)[1] | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 262,184 km2 (101,230 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 45,772,188 |

| • Estimate (2022)[2] | 51,670,000 |

| • Density | 173/km2 (450/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (Indian Standard Time) |

| Scheduled languages | |

| State/Regional official languages |

|

The region shares an international border of 5,182 kilometres (3,220 mi) (about 99 per cent of its total geographical boundary) with several neighbouring countries – 1,395 kilometres (867 mi) with China in the north, 1,640 kilometres (1,020 mi) with Myanmar in the east, 1,596 kilometres (992 mi) with Bangladesh in the south-west, 97 kilometres (60 mi) with Nepal in the west, and 455 kilometres (283 mi) with Bhutan in the north-west.[20] It comprises an area of 262,184 square kilometres (101,230 sq mi), almost 8 per cent of that of India. The Siliguri Corridor connects the region to the rest of mainland India.

The states of North Eastern Region are officially recognised under the North Eastern Council (NEC),[19] constituted in 1971 as the acting agency for the development of the north eastern states. Long after induction of NEC, Sikkim formed part of the North Eastern Region as the eighth state in 2002.[21][22] India's Look-East connectivity projects connect Northeast India to East Asia and ASEAN. The city of Guwahati in Assam is referred to as the "Gateway to the Northeast" and is the largest metropolis in Northeast India.

History

editThe earliest settlers may have been Austroasiatic speakers from Southeast Asia, followed by Tibeto-Burman speakers from China, and by 500 BCE Indo-Aryan speakers from the Gangetic Plains as well as Kra–Dai speakers from southern Yunnan and Shan State.[23] Due to the biodiversity and crop diversity of the region, archaeological researchers believe that early settlers of Northeast India had domesticated several important plants.[24] Historians believe that the 100 BCE writings of Chinese explorer Zhang Qian indicate an early trade route via Northeast India.[25] The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions a people called Sêsatai in the region,[26] who produced malabathron (cinnamon-like aromatic leaves, dried and used as a flavouring agent), so prized in the old world.[27] Ptolemy's Geographia (2nd century CE) calls the region Kirrhadia, apparently after the Kirata population.[28]

In the early historical period (most of the first millennium CE), Kamarupa straddled most of present-day Northeast India. Xuanzang, a travelling Chinese Buddhist monk, visited Kamarupa in the 7th century CE. He described the people as "short in stature and black-looking", whose speech differed a little from mid-India and who were of simple but violent disposition. He wrote that the people in Kamarupa knew of Sichuan, which lay to the kingdom's east beyond a treacherous mountain.[29]

The northeastern states were established during the British Raj of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when they became relatively isolated from traditional trading partners such as Bhutan and Myanmar.[30] Many of the peoples in present-day Mizoram, Meghalaya and Nagaland converted to Christianity under the influence of British (Welsh) missionaries.[31]

Formation of North Eastern states

editSince the Moamoria disturbances, the Ahom dynasty was on the decline. The British appeared on the scene in the guise of saviours.[32] In the early 19th century, both the Ahom and the Manipur kingdoms fell to a Burmese invasion.[32] The ensuing First Anglo-Burmese War resulted in the entire region coming under British control. In the colonial period (1826–1947), North East India was made a part of Bengal Province from 1839 to 1873, after which Colonial Assam became its own province,[33] but which included Sylhet.

After Indian Independence from British Rule in 1947, the Northeastern region of British India consisted of Assam and the princely states of Tripura Kingdom and Manipur Kingdom. Subsequently, Manipur and Tripura were made Union Territories of India in 1956 and in 1972 attained fully-fledged statehood. Later, Nagaland attained statehood in 1963, Meghalaya in 1972. Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram became full-fledged states on 20 February 1987, being carved out of the large territory of Assam.[34] Sikkim was integrated as the eighth North Eastern Council state in 2002.[21]

The city of Shillong served as the capital of the Assam province created during British Rule. It remained the capital of undivided Assam until the formation of the state of Meghalaya in 1972.[35] The capital of Assam was shifted to Dispur, a part of Guwahati, and Shillong was designated as the capital of Meghalaya.[citation needed]

| State | Historic Name | Capital(s) | Statehood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | North-East Frontier Agency | Itanagar | 1987 (earlier a Union Territory of India, constituted in 1971)[36] |

| Assam | Kamarupa | Shillong (till 1969), Dispur | 1947 |

| Manipur | Kangleipak[37] | Imphal | 1971 (earlier a Union Territory of India, constituted in 1956)[36] |

| Meghalaya | Khasi hills, Jaintia hills and Garo hills | Shillong | 1971[36] |

| Tripura | Tipperah[38] | Agartala | 1971 (earlier a Union Territory of India, constituted in 1956)[36] |

| Mizoram | Lushai Hills | Aizawl | 1987 (earlier a Union Territory of India, constituted in 1971)[36][39] |

| Nagaland | Naga Hills District | Kohima | 1963 |

| Sikkim | Sukhim | Gangtok | 1975 |

World War II

editInitially, the Japanese had invaded British territories in Southeast Asia, including Burma (now Myanmar), with the intention of creating a fortified perimeter around Japan. The British had neglected the defense of Burma, and by early 1942, the Japanese had captured Rangoon and pushed Allied forces back towards India through a grueling retreat.[40]

In response to the Japanese advance, the British formed the South East Asia Command (SEAC) under Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten in November 1943. This command brought new energy to the war effort in the region and emphasized the importance of standing firm and fighting on despite logistical challenges, such as during the monsoon season.[41]

The Japanese launched an offensive in March 1944 aimed at capturing Imphal and Kohima, key locations in northeast India. Capturing these areas would have allowed the Japanese to disrupt Allied supply lines to China and launch air attacks against India.[42]

However, the Allied forces, under the leadership of Field Marshal William Slim, held firm. They adopted aggressive tactics, including the creation of defensive "boxes" and the use of jungle warfare techniques. Despite being surrounded, the defenders at Kohima held out against intense Japanese attacks until reinforcements arrived.[43]

The battles of Imphal and Kohima resulted in a decisive defeat for the Japanese. They suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retreat, marking a turning point in the Burma Campaign. The Allied victory paved the way for subsequent offensives to clear Japanese forces from Burma and ultimately led to the re-conquest of the region.[44]

Sino-Indian War (1962)

editArunachal Pradesh, a state in the Northeastern tip of India, is claimed by China as South Tibet.[45] Sino-Indian relations degraded, resulting in the Sino-Indian War of 1962. The cause of the escalation into war is still disputed by both Chinese and Indian sources. During the war in 1962, the PRC (China) captured much of the NEFA (North-East Frontier Agency) created by India in 1954. But on 21 November 1962, China declared a unilateral ceasefire, and withdrew its troops 20 kilometres (12 mi) behind the McMahon Line. China returned Indian prisoners of war in 1963.[46]

Seven Sister States

editThe Seven Sister States is a popular term for the contiguous states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura prior to inclusion of the state of Sikkim into the North Eastern Region of India. The sobriquet 'Land of the Seven Sisters' was coined to coincide with the inauguration of the new states in January 1972 by Jyoti Prasad Saikia,[47] a journalist in Tripura, in the course of a radio talk show. He later compiled a book on the interdependence and commonness of the Seven Sister States. It has been primarily because of this publication that the nickname has caught on.[48]

Geography

editThe Northeast region can be physiographically categorised into the Eastern Himalaya, the Patkai and the Brahmaputra and the Barak valley plains. Northeast India (at the confluence of Indo-Malayan, Indo-Chinese, and Indian biogeographical realms) has a predominantly humid sub-tropical climate with hot, humid summers, severe monsoons, and mild winters. Along with the west coast of India, this region has some of the Indian subcontinent's last remaining rainforests, which support diverse flora and fauna and several crop species. Reserves of petroleum and natural gas in the region are estimated to constitute a fifth of India's total potential.[citation needed]

The region is covered by the mighty Brahmaputra-Barak river systems and their tributaries. Geographically, apart from the Brahmaputra, Barak and Imphal valleys and some flatlands in between the hills of Meghalaya and Tripura, the remaining two-thirds of the area is hilly terrain interspersed with valleys and plains; the altitude varies from almost sea-level to over 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) above MSL. The region's high rainfall, averaging around 10,000 millimetres (390 in) and above creates problems of the ecosystem, high seismic activity, and floods. The states of Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim have a montane climate with cold, snowy winters and mild summers.[citation needed]

-

Ropeway, Gangtok

-

Aerial view of Shillong

-

Neer Mahal of Tripura

-

-

Nohkalikai Falls, Cherrapunji, Meghalaya

Topography

editHighest peaks

editKangchenjunga, the third highest mountain peak in the world rising to an altitude of 8,586 m (28,169 ft), lies in-between the state Sikkim and adjacent country Nepal.

Brahmaputra river basin

editTributaries of the Brahmaputra River in Northeast India:

Climate

editNortheast India has a subtropical climate that is influenced by its relief and influences from the southwest and northeast monsoons.[49][50] The Himalayas to the north, the Meghalaya plateau to the south and the hills of Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur to the east influences the climate.[51] Since monsoon winds originating from the Bay of Bengal move northeast, these mountains force the moist winds upwards, causing them to cool adiabatically and condense into clouds, releasing heavy precipitation on these slopes.[51] It is the rainiest region in the country, with many places receiving an average annual precipitation of 2,000 mm (79 in), which is mostly concentrated in summer during the monsoon season.[51] Cherrapunji, located on the Meghalaya plateau is one of the rainiest place in the world with an annual precipitation of 11,777 mm (463.7 in).[51] Temperatures are moderate in the Brahmaputra and Barak valley river plains which decreases with altitude in the hilly areas.[51] At the highest altitudes, there is permanent snow cover.[51] In general, the region has 3 seasons: Winter, Summer, and rainy season in which the rainy season coincides with the summer months much like the rest of India.[52] Winter is from early November until mid March while summer is from mid-April to mid-October.[51]

Under the Köppen climate classification, the region is divided into 3 broad types: A (tropical climates), C (warm temperate mesothermal climates), and D (snow microthermal climates).[53][54] The tropical climates are located in parts of Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram, and the Cachar plains south of 25oN and are classified as tropical wet and dry (Aw).[53] Much of Assam, Nagaland, northern parts of Meghalaya and Manipur and parts of Arunachal Pradesh fall within the warm temperature mesothermal climates (type C) where the mean temperatures in coldest months range from −3 to 18 °C (27 to 64 °F).[54][55] The entire Brahmaputra valley has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa/Cwa) with hot summers.[54][55] At altitudes between 500 and 1,500 m (1,600 and 4,900 ft) located in the eastern hills of Nagaland, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh, a (Cfb/CWb) climate prevails with warm summers.[54][55] Locations above 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in Meghalaya, parts of Nagaland, and northern Arunachal Pradesh have a (Cfc/Cwc) climate with short and cool summers.[55] Finally, the extreme northern parts of Arunachal Pradesh are classified as humid continental climates with mean winter temperatures below −3 °C (27 °F).[54][56]

- Temperature

Temperatures vary by altitude with the warmest places being in the Brahmaputra and Barak River plains and the coldest at the highest altitudes.[57] It is also influenced by proximity to the sea with the valleys and western areas being close to the sea, which moderates temperatures.[57] Generally, temperatures in the hilly and mountainous areas are lower than the plains which lie at a lower altitude.[58] Summer temperatures tend to be more uniform than winter temperatures due to high cloud cover and humidity.[59]

In the Brahmaputra and Barak valley river plains, mean winter temperatures vary between 16 and 17 °C (61 and 63 °F) while mean summer temperatures are around 28 °C (82 °F).[57] The highest summer temperatures occur in the West Tripura plain with Agartala, the capital of Tripura having mean maximum summer temperatures ranging between 33 and 35 °C (91 and 95 °F) in April.[60] The highest temperatures in summer occur before the arrival of monsoons and thus eastern areas have the highest temperatures in June and July where the monsoon arrives later than western areas.[60] In the Cachar Plain, located south of the Brahmaputra plain, temperatures are higher than the Brahmaputra plain although the temperature range is smaller owing to higher cloud cover and the monsoons that moderate night temperatures year round.[58][60]

In the mountainous areas of Arunachal Pradesh, the Himalayan ranges in the northern border with India and China experience the lowest temperatures with heavy snow during winter and temperatures that drop below freezing.[58] Areas with altitudes exceeding 2,000 metres (6,562 ft) receive snowfall during winters and have cool summers.[58] Below 2,000 metres (6,562 ft) above sea level, winter temperatures reach up to 15 °C (59 °F) during the day with nights dropping to zero while summers are cool, with a mean maximum of 25 °C (77 °F) and a mean minimum of 15 °C (59 °F).[58] In the hilly areas of Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram, winters are cold while summers are cool.[59]

The plains in Manipur has colder winter minimums than what is warranted by its elevation owing to being surrounded by hills on all sides.[61] This is due to temperature inversions during winter nights when cold air descends from the hills into the valleys below and its geographic location which prevents winds that bring hot temperatures and humidity from coming into the Manipur plain.[61] For example, in Imphal, winter daytime temperatures hover around 21 °C (70 °F) but nighttime temperatures drop to 3 °C (37 °F).[61]

- Rainfall

No part of Northeast India receives less than 1,000 mm (39 in) of rainfall a year.[52] Areas in the Brahmputra valley receive 2,000 mm (79 in) of rainfall a year while mountainous areas receive 2,000 to 3,000 mm (79 to 118 in) a year.[52] The southwest monsoon is responsible for bringing 90% of the annual rainfall to the region.[62] April to late October are the months where most of the rainfall in Northeast India occurs with June and July being the rainiest months.[62] In most parts of the region, the average date of onset of the monsoons is 1 June.[63] Southern areas are the first to receive the monsoon (May or June) with the Brahmaputra valley and the mountainous north receiving later (later May or June).[62] In the hilly parts of Mizoram, the closer proximity to the Bay of Bengal causes it to experience early monsoons with June being the wettest season.[62]

High-risk seismic zone

editThe North Eastern Region of India is a mega-earthquake prone zone caused by active fault planes beneath formed by the convergence of three tectonic plates viz. India Plate, Eurasian Plate and Burma Plate. Historically the region has suffered from two great earthquakes (M > 8.0) – 1897 Assam earthquake and 1950 Assam-Tibet earthquake – and about 20 large earthquakes (8.0 > M > 7.0) since 1897.[64][65] The 1950 Assam-Tibet earthquake is still the largest earthquake in India.[citation needed]

Wildlife

editFlora

editWWF has identified the entire Eastern Himalayas as a priority Global 200 ecoregion. Conservation International has upscaled the Eastern Himalaya hotspot to include all the eight states of Northeast India, along with the neighbouring countries of Bhutan, southern China and Myanmar.

The region has been identified by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research as a center of rice germplasm. The National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (NBPGR), India, has highlighted the region as being rich in wild relatives of crop plants. It is the center of origin of citrus fruits. Two primitive variety of maize, Sikkim Primitive 1 and 2, have been reported from Sikkim (Dhawan, 1964). Although jhum cultivation, a traditional system of agriculture, is often cited as a reason for the loss of forest cover of the region, this primary agricultural economic activity practised by local tribes supported the cultivation of 35 varieties of crops. The region is rich in medicinal plants and many other rare and endangered taxa. Its high endemism in both higher plants, vertebrates, and avian diversity has qualified it as a biodiversity hotspot.

The following figures highlight the biodiversity significance of the region:[66]

- 51 forest types are found in the region, broadly classified into six major types – tropical moist deciduous forests, tropical semi-evergreen forests, tropical wet evergreen forests, subtropical forests, temperate forests, and alpine forests.

- Out of the nine important vegetation types of India, six are found in the North Eastern Region.

- These forests harbour 8,000 out of 15,000 species of flowering plants. In floral species richness, the highest diversity is reported from the states of Arunachal Pradesh (5000 species) and Sikkim (4500 species) amongst the North Eastern states.

- According to the Indian Red Data Book, published by the Botanical Survey of India, 10 per cent of the flowering plants in the country are endangered. Of the 1500 endangered floral species, 800 are reported from Northeast India.

- Most of the North Eastern states have more than 60% of their area under forest cover, a minimum suggested coverage for the hill states in the country in order to protect from erosion.

- Northeast India is a part of Indo-Burma hotspot. This hotspot is the second largest in the world, next only to the Mediterranean Basin, with an area 2,206,000 square kilometres (852,000 sq mi) among the 25 identified.[citation needed]

Fauna

editThe International Council for Bird Preservation, UK identified the Assam plains and the Eastern Himalaya as an Endemic Bird Area (EBA). The EBA has an area of 220,000 km2 following the Himalayan range in the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Nepal, Myanmar and the Indian states of Sikkim, North Bengal, Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya and Mizoram. Because of a southward occurrence of this mountain range in comparison to other Himalayan ranges, this region has a distinctly different climate, with warmer mean temperatures and fewer days with frost, and much higher rainfall. This has resulted in the occurrence of a rich array of restricted-range bird species. More than two critically endangered species, three endangered species, and 14 vulnerable species of birds are in this EBA. Stattersfield et al. (1998) identified 22 restricted range species, out of which 19 are confined to this region and the remaining three are present in other endemic and secondary areas. Eleven of the 22 restricted-range species found in this region are considered as threatened (Birdlife International 2001), a number greater than in any other EBA of India.[citation needed]

Northeast India is very rich in faunal diversity. There are as many as 15 species of non-human primates and most important of them are hoolock gibbon, stumptied macaque, pigtailed macaque, golden langur, hanuman langur and rhesus monkey. The most important and endangered species is one-horned rhinoceros. The forests of the region are also the habitats of elephant, royal Bengal tiger, leopard, golden cat, fishing cat, marbled cat, Bengal fox etc. the Gangetic dolphin in the Brahmaputra is also an endangered species. The other endangered species are otter, mugger crocodile, tortoise and some fishes.[67]

WWF has identified the following priority ecoregions in North-East India:

- Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests

- Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests

- Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests

- Northeast India–Myanmar pine forests

National parks

editState symbols

edit| Arunachal Pradesh | Assam | Manipur | Meghalaya | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | Mithun (Bos frontalis) | Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) | Sangai (Rucervus eldii eldii) | Clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) | ||||

| Bird | Hornbill (Buceros bicornis) | White-winged duck (Asarcornis scutulata) | Mrs. Hume's pheasant (Syrmaticus humiae) | Hill myna (Gracula religiosa) | ||||

| Flower | Foxtail orchid (Rhynchostylis retusa) | Foxtail orchid (Rhynchostylis retusa) | Siroi lily (Lilium mackliniae) | Lady's Slipper Orchid (Paphiopedilum insigne) | ||||

| Tree | Hollong (Dipterocarpus macrocarpus) | Hollong (Dipterocarpus macrocarpus) | Uningthou (Phoebe hainesiana) | Gamhar (Gmelina arborea) | ||||

| Mizoram | Nagaland | Sikkim | Tripura | |||||

| Animal | Himalayan serow (Capricornis thar) | Mithun (Bos frontalis) | Red panda (Ailurus fulgens) | Phayre's leaf monkey (Trachypithecus phayrei) | ||||

| Bird | Mrs. Hume's pheasant (Syrmaticus humiae) | Blyth's tragopan (Tragopan blythii) | Blood pheasant (Ithaginis cruentus) | Green imperial pigeon (Ducula aenea) | ||||

| Flower | Red Vanda (Renanthera imschootiana) | Tree rhododendron (Rhododendron arboreum) | Noble dendrobium (Dendrobium nobile) | Indian rose chestnut (Mesua ferrea) | ||||

| Tree | Indian rose chestnut (Mesua ferrea) | Alder (Alnus nepalensis) | Rhododendron (Rhododendron niveum) | Agarwood (Aquilaria agallocha) | ||||

Demographics

editThe total population of Northeast India is 46 million with 68 per cent of that living in Assam alone. Assam also has a higher population density of 397 persons per km2 than the national average of 382 persons per km2. The literacy rates in the states of the Northeastern region, except those in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, are higher than the national average of 74 per cent. As per 2011 census, Meghalaya recorded the highest population growth of 27.8 per cent among all the states of the region, higher than the national average at 17.64 per cent; while Nagaland recorded the lowest in the entire country with a negative 0.5 per cent.[73]

| State | Population | Males | Females | Sex Ratio | Literacy % | Rural Population | Urban Population | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | 1,383,727 | 713,912 | 669,815 | 938 | 65.38 | 870,087 | 227,881 | 83,743 | 17 |

| Assam | 31,205,576 | 15,939,443 | 15,266,133 | 958 | 72.19 | 23,216,288 | 3,439,240 | 78,438 | 397 |

| Manipur | 2,570,390 | 1,290,171 | 1,280,219 | 992 | 79.21 | 1,590,820 | 575,968 | 22,327 | 122 |

| Meghalaya | 2,966,889 | 1,491,832 | 1,475,057 | 989 | 74.43 | 1,864,711 | 454,111 | 22,429 | 132 |

| Mizoram | 1,097,206 | 555,339 | 541,867 | 976 | 91.33 | 447,567 | 441,006 | 21,081 | 52 |

| Nagaland | 1,978,502 | 1,024,649 | 953,853 | 931 | 79.55 | 1,647,249 | 342,787 | 16,579 | 119 |

| Sikkim | 610,577 | 323,070 | 287,507 | 890 | 81.42 | 480,981 | 59,870 | 7,096 | 86 |

| Tripura | 3,673,917 | 2,087,059 | 2,086,858 | 960 | 91.58 | 2,639,134 | 1,534,783 | 10,486 | 350 |

Largest cities by population

editAccording to 2011 Census of India, the largest cities in Northeast India are

| Rank | City | Type | State | Population | Rank | City | Type | State | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guwahati | City | Assam | 968,549 | 9 | Jorhat | UA | Assam | 153,889 |

| 2 | Agartala | City | Tripura | 622,613 | 10 | Nagaon | UA | Assam | 147,496 |

| 3 | Imphal | UA | Manipur | 414,288 | 11 | Bongaigaon | UA | Assam | 139,650 |

| 4 | Dimapur | City | Nagaland | 379,769 | 12 | Tinsukia | UA | Assam | 126,389 |

| 5 | Shillong | UA | Meghalaya | 354,325 | 13 | Tezpur | UA | Assam | 102,505 |

| 6 | Aizawl | City | Mizoram | 291,822 | 14 | Kohima | UA | Nagaland | 100,000 |

| 7 | Silchar | UA | Assam | 229,136 | 15 | Gangtok | City | Sikkim | 98,658 |

| 8 | Dibrugarh | UA | Assam | 154,296 | 16 | Itanagar | City | Arunachal Pradesh | 95,650 |

|

UA: Urban Agglomeration[74] | |||||||||

Languages

editNortheast India constitutes a single linguistic region within the Indian national context, with about 220 languages in multiple language families (Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Kra–Dai, Austroasiatic, as well as some creole languages) that share a number of features that set them apart from most other areas of the Indian subcontinent (such as alveolar consonants rather than the more typical dental/retroflex distinction).[75][76] Assamese, an Indo-Aryan language spoken mostly in the Brahmaputra Valley, developed as a lingua franca for many speech communities. Assamese-based pidgin/creoles have developed in Nagaland (Nagamese) and Arunachal (Nefamese),[77] though Nefamese has been replaced by Hindi in recent times. Bengali language is another Indo-Aryan language spoken in South Assam in the Barak Valley and Tripura, being the majority and official language in both the regions. The Austro-Asiatic family is represented by the Khasi, Jaintia and War languages of Meghalaya. A small number of Tai–Kadai languages (Ahom, Tai Phake, Khamti, etc.) are also spoken. Sino-Tibetan is represented by a number of languages that differ significantly from each other,[78] some of which are: Boro, Rabha, Karbi, Mising, Tiwa, Deori, Hmar (including Biate, Chorei, Halam, Hrangkhawl, Kaipeng, Molsom, Ranglong, Saihriem, Sakachep, Thangachep, Thiek), Zeme Naga, Rengma Naga and, Kuki (Thadou language) (Assam); Garo, Rabha, Hmar (including Biate, Sakachep) (Meghalaya); Ao, Angami, Sema, Lotha, Konyak, Chakhesang, Chang, Khiamniungan, Phom, Pochury, Rengma, Sangtam, Tikhir, Yimkhiung, Zeliang, Kuki (Thadou), and Hmar (including Sakachep/Khelma) etc. (Nagaland); Mizo languages such as Lusei (including Hualngo), Hmar (including Chorei, Darlawng, Darngawn, Kaipeng, Khawlhring, Molsom, Ngente, Sakachep, Zote), Lai (including Hakha, Falam, Khualsim, Zanniet, Sim), Mara languages, Ralte/Galte, Zomi/Paihte, Kuki/Thahdo, etc. (Mizoram); Hrusso, Tanee, Niyshi, Adi, Abor, Nocte, Apatani, Mishmi etc. (Arunachal). Kokborok is the dominant among the tribal people of Tripura and one of the official languages of the state, while Garo, Hmar (including Bong, Bongcher, Chorei, Dab, Darlawng, Hmarchaphang, Hrangkhawl, Langkai, Kaipeng, Koloi, Korbong, Molsom, Ranglong, Rupini, Saihmar, Sakachep, Thangachep)), Lusei (including Rokhum), etc are also spoken. Meitei is the official language in Manipur, the dominant language of the Imphal Valley; while "Naga" languages such as Poumai, Mao, Maram, Rongmei (Kabui),Tangkhul, Zeme, Liangmei, Inpui, Thangal Naga and Mizo languages such as Kuki/Thado, Lusei, Zomi languages (including Paite, Simte, Vaiphei, Zou, Mate, Thangkhal, Tedim-Chin), Gangte and Hmar languages (including Biete, Hrangkhawl, Thiek, Zote) predominate in individual hill areas of the state.[79]

Among other Indo-Aryan languages, Chakma is spoken in Mizoram and Hajong in Assam and Meghalaya. Nepali, an Indo-Aryan language, is dominant in Sikkim, besides the Sino-Tibetan languages Limbu, Bhutia, Lepcha, Rai, Tamang, Sherpa, etc. Bengali was made the official language of Colonial Assam from 1836 to 1873.[82]

Official languages

edit| State | Official Languages[83] |

|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | English |

| Assam | Assamese, Bodo, Meitei (Manipuri),[15] Bengali[84] |

| Manipur | Meitei |

| Meghalaya | English |

| Mizoram | Mizo, English |

| Nagaland | English[85] |

| Sikkim | Sikkimese, Lepcha, Nepali, English[17] |

| Tripura[86] | Bengali, Kokborok, English |

Etymology of state names

edit| Name of state | Origin | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Sanskrit | Land of the dawn-lit mountains |

| Assam | native name | Both Assam and Ahom are from asam, acam, a corruption of Shan/Shyam as used for the Ahoms.[87] |

| Manipur | Sanskrit | Land abundant with jewels, adopted in the 18th century |

| Meghalaya | Sanskrit | Abode of the clouds, coined by Shiba P. Chatterjee |

| Mizoram | Mizo language | Land of the Mizo people; Ram means land |

| Nagaland | English | Land of the Naga people |

| Sikkim | Limbu language | New House – Derived from the word "Sukhim", "Su" meaning new and "Khim" meaning house |

| Tripura | Kokborok | Sanskrit version of native names: Tipra, Tuipura, Twipra etc. It literally means Land near the Water – Derived from the word "TWIPRA", "Twi" meaning water and "Bupra" meaning near, as Tripura is slightly near the Bay of Bengal. |

Religions

editReligion in Northeast India (2011)

Hinduism is the majority religion in the North Eastern states of Assam, Tripura, Manipur, Sikkim and plurality in Arunachal Pradesh, while Christianity is the majority religion in Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram and plurality in Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. A significant plurality of the state of Arunachal Pradesh follows the indigenous religion Donyi-Polo. Islam has a significant presence in Assam and about 93% of all North East Muslim population is concentrated in that state alone. A bulk of Christian population in India resides in North East, as about 30% of India's Christian population is concentrated in North Eastern region alone. There is a significant presence of Buddhism in Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram.[88]

| State | Hinduism | Islam | Christianity | Buddhism | Jainism | Sikhism | Other Religions | Religion Not Stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | 401,876 | 27,045 | 418,732 | 162,815 | 771 | 3,287 | 362,553 | 6,648 |

| Assam | 19,180,759 | 10,679,345 | 1,165,867 | 54,993 | 25,949 | 20,672 | 27,118 | 50,873 |

| Manipur | 1,181,876 | 239,836 | 1,179,043 | 7,084 | 1,692 | 1,527 | 233,767 | 10,969 |

| Meghalaya | 342,078 | 130,399 | 2,213,027 | 9,864 | 627 | 3,045 | 258,271 | 9,578 |

| Mizoram | 30,136 | 14,832 | 956,331 | 93,411 | 376 | 286 | 808 | 1,026 |

| Nagaland | 173,054 | 48,963 | 1,739,651 | 6,759 | 2,655 | 1,890 | 3,214 | 2,316 |

| Sikkim | 352,662 | 9,867 | 60,522 | 167,216 | 314 | 1,868 | 16,300 | 1,828 |

| Tripura | 3,063,903 | 316,042 | 159,882 | 125,385 | 860 | 1,070 | 1,514 | 5,261 |

| Total | 24,726,344 | 11,466,329 | 7,893,055 | 627,527 | 33,244 | 33,645 | 903,545 | 88,499 |

Ethnic groups

editNortheast India has over 220 ethnic groups and an equal number of dialects in which Bodo form the largest indigenous ethnic group.[90] The hills states in the region like Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland are predominantly inhabited by tribal people with a degree of diversity even within the tribal groups. The region's population results from ancient and continuous flows of migrations from Tibet, Indo-Gangetic India, the Himalayas, present Bangladesh, and Myanmar.[91]

Majority communities

editThese ethnic groups form significant majorities in the states/regions of Northeast India:

- Assamese people - (48.38%), largest ethnicity in Assam

- Tani People - (40.32%), largest ethnicity in Arunachal Pradesh

- Bodo people - (30.47%), largest ethnicity in Bodoland region of Assam

- Bengali people - (63.48% and 80.84%), largest ethnicity in Tripura state and Barak Valley region of Assam

- Meitei people - (53.3%), largest ethnicity in Manipur

- Tripuri people - largest ethnicity in Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council of Tripura

- Mizo people - (73.14%), largest ethnicity in Mizoram

- Khasi people - (46.24%), largest ethnicity in Meghalaya

- Naga people - (88.24%), largest ethnicity in Nagaland

- Nepali people - (62.6%), largest ethnicity in Sikkim

- Sikkimese people - native ethnicity of Sikkim

Minority communities

editThese ethnic groups form minorities in the states of Northeast India:

- Bhojpuri

- Bishnupriya

- Biate

- Bodo

- Chakma

- Deori

- Dimasa

- Garo

- Hajong

- Hmar

- Karbi

- Kami (caste)

- Khampti

- Koch Rajbongshi

- Kom

- Lepcha

- Limbu

- Lotha Naga

- Miji

- Miyas

- Mara

- Mishmi

- Nyishi

- Nepali

- Paite

- Pnar

- Purvottar maithili

- Rabha

- Ranglong (Langrong)

- Rai

- Singpho

- Sylheti

- Tamang

- Tiwa

- Tripuri

- Kuki people (Kuki: Thadou, Baite, Mate, Khongsai, Haokip, Doungel, Hangmi, Touthang, Kipgen, Hangmi, Neisel, Chongloi, Hangsing, Guite, etc.)

-

British India map of Northeast India by ethnicity and Language, 1891

-

A Naga warrior in 1960

-

Shad suk Mynsiem, a Khasi festival

-

Traditional Hajong Clothing

-

Aka tribe, Arunachal Pradesh

-

Mizo school girls

-

Princess of Sikkim in traditional royal dress

-

Tripuri woman in traditional attire

-

Asamiya youth in Bihu attire.

Culture

editCuisines

edit| State | Staple diet | Popular dishes |

|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Rice, fish, meat, leaf vegetables | Thukpa, momo, apong (rice beer) |

| Assam | Rice, fish, meat, leaf vegetable | Assam tea, Pitha (rice cakes), Khar (alkali), Khar-Matidail, Ou-tenga-Maasor-Jul, Pura-Maas, Alu-Pitika, Pani-Tenga, Kharoli, Khorisa (bamboo shoot), Xukan Maasor Xukoti, Pointa-Bhaat, Tupula-Bhaat, Sunga-Sawul (rice cooked in bamboo), Kharikat Diya Maas, Kharikat Dia-Mangxo, Pati-Hanhor-Mangxo-Jul (duck stew), Lai-Xak-Gahori-Mangxo (pork with mustard greens), Kumol Sawul-Doi Jolpaan, Tamul (betel nut) – paan, rice beer (Judima, Rohi, Xaj Pani, Apong, etc.) |

| Manipur | Rice, fish, local vegetables | Eromba, u-morok, singju, ngari (fermented fish), kangshoi |

| Meghalaya | Rice, spiced meat, fish | Khasi dishes – Thungtap, Dohjem, Thungrumbai, Jadoh, ki kpu, Garo dishes – kappa, brenga, so•tepa, wa•tepa, pura, minil, na•kam (dried fish), bamboo shoot |

| Mizoram | Rice, fish, meat | Bai, bekang (fermented soya beans), sa-um (fermented pork), sawhchiar |

| Nagaland | Rice, meat, stewed or steamed vegetables | fermented bamboo shoot, smoked pork and beef, axone, galho, bhut jolokia |

| Sikkim | Rice, meat, dairy products | Thukpa, momo, sha Phaley, gundruk, sinki, sel roti |

| Tripura | Rice, meat, vegetables | Maidul (rice ball), Awang bangwi, Awang sokrang, Chakhūi, Gudok, Mosodeng, Awandru, Mūkhūi, Hangjak, Yikjak, Wahan mosodeng, Muiya (bamboo shoot), Berma Bwtwi (fermented fish) |

-

Bangwi - Tripuri food of Tripura

-

Paknam (Manipur)

-

Basic Tripuri lunch thali

-

Smoked freshwater fish (Manipur)

-

North Sikkim meal

-

Assamese thali

-

Red rice with pork (Arunachal Pradesh)

Arts

editThe Manipuri Raas Leela dance (from Manipur) and the Sattriya (from Assam) have been included in the elite category of the "Classical Dances of India", as officially recognised by both the Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Ministry of Culture (India). Besides these, all tribes in Northeast India have their own folk dances associated with their religion and festivals. The tribal heritage in the region is rich with the practice of hunting, land cultivation and indigenous crafts. The rich culture is vibrant and visible with the traditional attires of each community.[citation needed]

All states in Northeast India share the handicrafts of bamboo and cane, wood carving, making traditional weapons and musical instruments, pottery and handloom weaving. Traditional tribal attires are made of thick fabrics primarily with cotton.[92] Assam silk is a famous industry in the region.

| State | Traditional Performing Arts | Traditional Visual Arts | Traditional Crafts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Wancho dances, Idu Mishmi dance, Digaru Mishmi Buiya dance, Khampti dance, Ponung dance, Sadinuktso[93] | Cane and bamboo, cotton and wool weaving, wood carving, blacksmithy (hand tools, weapons, ornaments, dishes, sacred bells and smoking pipes)[93][94] | |

| Assam | Sattriya, Bagurumba, Bihu dance, Bhaona (For more see Music of Assam) | Hastividyarnava (For more see Painting of Assam and Fine Arts of Assam) | Cane and bamboo, bell metal and brass, silk, toys, and mask making, pottery and terracotta, jewellery, musical instruments making, boat making, paints. |

| Manipur | Manipuri dance (Ras Lila), Kartal Cholom, Manjira Cholom, Khubak Eshei, Pung Cholom, Lai-Haraoba | Cotton textile, bamboo crafts (hats, baskets), pottery[94][92] | |

| Meghalaya | Nongkrem, Shad suk, Behdienkhlam, Wangala, Lahoo dance[95][94] (For more see Music of Meghalaya) | Making hand tools and weapons, musical instruments (drums), cane and bamboo work, weaving traditional attires, jewellery making (gold, coral, glass), wall engravings, wood carving[94][96] | |

| Mizoram | Cheraw, Khual Lam, Chheih Lam, Chai Lam, Rallu Lam, Sarlamkai/Solakia, Par Lam, Sakei Lu Lam[97] (For more see Music of Mizoram), Bizhu Dance | Traditional hand tools, weapons and textile work, bamboo and cane handicrafts[98][94] | |

| Nagaland | Zeliang dance, war dance, Nruirolians (cock dance) (For more see Music of Nagaland) | Cane and bamboo crafts, traditional hand tools, weapons and textile work, wood carving, pottery, ornaments for traditional attire, musical instruments (drum and trumpet)[94] | |

| Sikkim | Chu Faat dance, Lu Khangthamo, Gha To Kito, Rechungma, Maruni, Tamang Selo, Singhi Chaam, Yak Chaam, Khukuri dance, Rumtek Chaam (mask dance) Chyabrung[99][100][101] (See also Music of Sikkim) | Thangka (showcasing Buddhist teachings on cotton canvas using vegetable dyes)[100] | Handmade paper, carpet making, woollen textile, wood carving[100] |

| Tripura | Tripuri dances, Mamita dance, Goria dance, Lebang dance, Mosak sulmani dance, Hojagiri dance, Bizhu dance, Wangala, Hai-hak dance, Sangrai dance, Owa dance | Rock curbings of different gods and goddesses | Cane and bamboo, Traditional cotton textiles, weaving and handloom, moluwa /sitalpati(mat making), wood carving,[94] string and wind musical instruments |

-

Assamese youths performing Bihu dance.

-

Nyokum festival of Nyishi tribe (Arunachal Pradesh)

-

-

-

Dance of Angami tribe (Nagaland)

Music

editNortheast is a hub of different genres of music. Each community has its own rich heritage of folk music. Talented musicians and singers are plentifully found in this part of the country. The Assamese singer-composer Bhupen Hazarika achieved national and international fame with his remarkable creations. Another famous singer from Assam, Pratima Barua Pandey is a well-known folk singer. Zubeen Garg, Papon, Anurag Saikia are some other notable singers, musicians from the state of Assam. Tangkhul Naga folk blue singer like Rewben Mashangva, who comes from Ukhrul, is an acclaimed Folk singer whose music is inspired by the like of Bob Dylan and Bob Marley. Another famous folk singing band from Nagaland popularly known as Tetseo Sisters is one to be noted for their original music genre. However, younger generation has started pursuing western music more and more nowadays. The northeast region has seen a significant increase in musical innovation in the 21st century.[102]

Literature

editMany of the Northeast Indian indigenous communities have an ancient heritage of folktales which tell the tale of their origin, rituals, beliefs and so on. These tales are transmitted from one generation to another in oral form. They are remarkable instances of tribal wisdom and imagination. However, Assam, Tripura and Manipur have some ancient written texts. These states were mentioned in the great Hindu epic Mahabharata. The Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by Madhava Kandali is considered the first translation of the Sanskrit Ramayana into a modern Indo-Aryan Language. Karbi Ramayana bears witness to the old heritage of written literature in Assam. Two writers from the Northeast, viz., Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya and Mamoni Raisom Goswami, have been awarded Jnanpith, the highest literary award in India.[103] Hence, Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya was the first Assamese writer and from the Northeast India to receive Jnanpith Award for his Assamese novel Mrityunjay (1979).[104] Mamoni Raisom Goswami was awarded the Jnanpith Award in the year 2000.[103] Nagen Saikia is the first writer from Assam and the Northeast India, to have been conferred the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship by the Sahitya Akademi.[105][106] Some of the notable writers of Northeast Literature are--(from Assam) Lakshminath Bezbaroa, Homen Borgohain, Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya, Harekrishna Deka, Rongbong Terang, Nilmani Phukan, Indira Goswami, Hiren Bhattacharyya, Mitra Phukan, Jahnavi Barua, Dhruba Hazarika, Rita Chowdhury; (from Arunachal Pradesh) Mamang Dai; (from Manipur) Robin S Ngangom, Ratan Thiyam; (from Meghalaya) Paul Lyngdoh; (from Nagaland) Temsula Ao, Easterine Kire; (from Sikkim) Rajendra Bhandari. Temsula Ao is the first writer from Northeast India to be awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award (2013) in the Indian English Literature category for her collection of short stories, Laburnum for My Head, and Padma Shri (2007). Easterine Kire is the first English novelist hailed from Nagaland. She received The Hindu Literary Prize (2015) for her novel When the River Sleeps. Indira Goswami, alias Mamoni Roisom Goswami, is an acclaimed Assamese writer whose novels include Moth-Eaten Howda of the Tusker, Pages Stained with Blood, The Shadow of Kamakhya and The Blue-Necked God. Mamang Dai won the Sahitya Akademi Award (2017) for her novel The Black Hill.[107]

Festivals

editIndigenous festivals in the northeast include the Ojiale festival of the Wancho people, Chhekar festival of the Sherdukpen people, Longte Yullo festival of Nishis, Solung festival of Adis, Losar festival of Monpas, Reh festival of Idu Mishmis and Dree festival of Apatani. Mamita Tripurabda(Tring festival), Buisu, Hangrai, Hojagiri, Kharchi and Garia festivals of Tripura, [108] In Manipur popular festivals include Ningol Chakouba and the Manipur boat racing festival or the Heikru Hidongba, Chasok Tangnam festival of Limbu people.

Sport

editNortheast India is notable for playing sports that are not very popular in the rest of India. These sports include football, with Mizoram's Talimeren Ao having served as the first captain of the national team in 1948,[109] and a growing presence of baseball in Manipur.[110]

Administration and political disputes

editInternational borders management

edit- McMahon Line and China–India border crossings patrolled by Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Special Frontier Force with China along Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh

- India-Bangladesh border and crossings patrolled by Border Security Force along Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram

- India–Myanmar border, crossings patrolled by Assam Rifles and Indian Army along Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram

- India-Bhutan borders patrolled by Sashastra Seema Bal along Sikkim, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh

- India-Nepal border patrolled by Sashastra Seema Bal along Sikkim

Pan-states development authorities

editStates and sub-divisions

edit| State | Code | Capital | Districts | Sub-division Type | Number of Subdivisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | IN-AR | Itanagar | 20 | Circle | 149 |

| Assam | IN-AS | Dispur | 35 | Sub-division | 78 |

| Manipur | IN-MN | Imphal | 16 | Sub-division | 38 |

| Meghalaya | IN-ML | Shillong | 12 | Community Development Block | 39 |

| Mizoram | IN-MZ | Aizawl | 11 | Community Development Block | 22 |

| Nagaland | IN-NL | Kohima | 16 | Circle | 33 |

| Sikkim | IN-SK | Gangtok | 6 | Sub-division | 9 |

| Tripura | IN-TR | Agartala | 8 | Sub-division | 23 |

| State | Autonomous Division | Establishment |

|---|---|---|

| Assam | Bodoland Territorial Area Districts | February 2003 |

| Dima Hasao district | February 1970 | |

| Karbi Anglong district | February 1970 | |

| Mising Autonomous Council | 1995 | |

| Rabha Hasong Autonomous Council | 1995 | |

| Manipur[111][112] | Churachandpur Autonomous District Council | 1971 |

| Chandel Autonomous District Council | 1971 | |

| Senapati Autonomous District Council | 1971 | |

| Sadar Hills Autonomous District Council | 1971 | |

| Tamenglong Autonomous District Council | 1971 | |

| Ukhrul Autonomous District Council | 1971 | |

| Meghalaya | Garo Hills Autonomous District Council | |

| Jaintia Hills Autonomous District Council | July 2012 | |

| Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council | ||

| Mizoram | Chakma Autonomous District Council | April 1972 |

| Lai Autonomous District Council | April 1972 | |

| Mara Autonomous District Council | May 1971 | |

| Tripura | Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council | January 1982 |

Government

editThe northeastern states, having 3.8% of India's total population, are allotted 25 out of a total of 543 seats in the Lok Sabha. This is 4.6% of the total number of seats.[citation needed]

| State | Chief Minister[113] | Governor[114] | High Court | Chief Justice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Pema Khandu | Kaivalya Trivikram Parnaik | Guwahati High Court (Itanagar Bench) | Sandeep Mehta, Chief Justice |

| Assam | Himanta Biswa Sarma | Gulab Chand Kataria | Guwahati High Court | Sandeep Mehta, Chief Justice |

| Manipur | Nongthombam Biren Singh | Anusuiya Uikye | Manipur High Court | Justice Siddharth Mridul |

| Meghalaya | Conrad Sangma | Phagu Chauhan | Meghalaya High Court | Justice Sanjib Banerjee |

| Mizoram | Lalduhoma | Kambhampati Hari Babu | Guwahati High Court (Aizawl Bench) | Sandeep Mehta, Chief Justice |

| Nagaland | Neiphiu Rio | La Ganesan | Guwahati High Court (Kohima Bench) | Sandeep Mehta, Chief Justice |

| Sikkim | Prem Singh Tamang | Ganga Prasad | Sikkim High Court | Justice Satish K. Agnihotri |

| Tripura | Manik Saha | Indrasena Reddy | Tripura High Court | Justice T. A. Gaur |

20th century separatist unrest

editIn 1947 Indian independence and partition resulted in the North East becoming a landlocked region. This exacerbated the isolation that has been recognised, but not studied. East Pakistan controlled access to the Indian Ocean.[115] The mountainous terrain has hampered the construction of road and railways connections in the region.[citation needed]

Several militant groups have formed an alliance to fight against the governments of India, Bhutan, and Myanmar, and now use the term "Western Southeast Asia" (WESEA) to refer to the region.[116] The separatist groups include the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP), Kanglei Yawol Kanna Lup (KYKL), People's Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK), People's Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak-Pro (PREPAK-Pro), Revolutionary People's Front (RPF) and United National Liberation Front (UNLF) of Manipur, Hynniewtrep National Liberation Council (HNLC) of Meghalaya, Kamatapur Liberation Organization (KLO), which operates in Assam and North Bengal, National Democratic Front of Bodoland and ULFA of Assam, and the National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT).[117]

Economy

editThe Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (MDoNER) is the deciding body under Government of India for socio-economic development in the region. The North Eastern Council under MDoNER serves as the regional governing body for Northeast India. The North Eastern Development Finance Corporation Ltd. (NEDFi) is a public limited company providing assistance to micro, small, medium and large enterprises within the northeastern region (NER). Other organisations under MDoNER include North Eastern Regional Agricultural Marketing Corporation Limited (NERAMAC), Sikkim Mining Corporation Limited (SMC) and North Eastern Handlooms and Handicrafts Development Corporation (NEHHDC).

List of NE states by NSDP 2023-24

edit| Rank | State | NSDP in

Indian Rupees ₹ |

NSDP in

US Dollars $ |

NSDP Per Capita

in ₹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Assam | ₹ 5,67,000 crore | $69 Billions | ₹ 1,58,734 |

| 2 | Tripura | ₹ 89,000 crore | $8 Billions | ₹ 2,14,458 |

| 3 | Sikkim | ₹ 47,331 crore | $3.88 Billions | ₹ 6,85,957 |

| 4 | Meghalaya | ₹ 46,600 crore | $5 Billions | ₹ 1,39,104 |

| 5 | Manipur | ₹ 45,145 crore | $5.52 Billions | ₹ 1,39,768 |

| 6 | Arunachal Pradesh | ₹ 37,870 crore | $4.6 Billions | ₹ 2,07,506 |

| 7 | Nagaland | ₹ 37,300 crore | $3.79 Billions | ₹ 90,666 |

| 8 | Mizoram | ₹ 35,904 crore | $4.3 Billion | ₹ 2,89,548 |

Industries

editAgriculture

editThe economy is agrarian. Little land is available for settled agriculture. Along with settled agriculture, jhum (slash-and-burn) cultivation is still practised by a few indigenous groups of people. The inaccessible terrain and internal disturbances have made rapid industrialisation difficult in the region.[citation needed]

Tourism

editLiving Root Bridges

Northeast India is also the home of many living root bridges. In Meghalaya, these can be found in the southern Khasi and Jaintia Hills.[118][119][120] They are still widespread in the region, though as a practice they are fading out, with many examples having been destroyed in floods or replaced by more standard structures in recent years.[121] Living root bridges have also been observed in the state of Nagaland, near the Indo-Myanmar border.[122]

Newspapers and Magazines

editNortheast India has several newspapers in both English and regional languages. The largest circulated English daily in Assam is The Assam Tribune. In Meghalaya, The Shillong Times is the highest circulated newspaper. In Nagaland, Nagaland Post has the highest number of readers. G Plus is the only print and digital English weekly tabloid published from Guwahati. In Manipur, Imphal Free Press is a highly respected newspaper. In Arunachal Pradesh, The Arunachal Times is the highest circulated newspaper in Arunachal Pradesh.[citation needed]

Transportation

editAir

editStates in the North Eastern Region are well connected by air-transport conducting regular flights to all major cities in the country. The states also own several small airstrips for military and private purposes which may be accessed using Pawan Hans helicopter services. The region currently has two international airports viz. Lokapriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport, Bir Tikendrajit International Airport Maharaja Bir Bikram Airport conducting flights to Thailand, Myanmar, Nepal and Bhutan. While the airport in Sikkim is under-construction, Bagdogra Airport (IATA: IXB, ICAO: VEBD) remains the closest domestic airport to the state.

| State | Airport | City | IATA Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal Pradesh | Itanagar Airport | Itanagar | HGI |

| Assam | Dibrugarh Airport | Dibrugarh | DIB |

| Jorhat Airport | Jorhat | JRH | |

| Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport | Guwahati | GAU | |

| Lilabari Airport | Lakhimpur | IXI | |

| Rupsi Airport | Dhubri | RUP | |

| Silchar Airport | Silchar | IXS | |

| Tezpur Airport | Tezpur | TEZ | |

| Manipur | Bir Tikendrajit International Airport | Imphal | IMF |

| Meghalaya | Baljek Airport | Tura | VETU (ICAO) |

| Shillong Airport | Shillong | SHL | |

| Mizoram | Lengpui Airport | Aizawl | AJL |

| Nagaland | Dimapur Airport | Dimapur | DMU |

| Sikkim | Pakyong Airport | Gangtok | PYG |

| Tripura | Maharaja Bir Bikram Airport | Agartala | IXA |

Railway

editRailway in Northeast India is delineated as Northeast Frontier Railway zone of Indian Railways. The regional network is underdeveloped. States of Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Sikkim will remain almost disconnected till March 2023 when the capital cities of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland are expected to get the rail links once the under construction rail projects are completed.[123]

Look East Policy

editIn the 21st century, there has been recognition among policymakers and economists of the region that the main stumbling block for economic development of the Northeastern region is the disadvantageous geographical location.[124] It was argued that globalisation propagates deterritorialisation and a borderless world which is often associated with economic integration. With 98 per cent of its borders with China, Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal, Northeast India appears to have a better scope for development in the era of globalisation.[125] As a result, a new policy developed among intellectuals and politicians that one direction the Northeastern region must be looking to as a new way of development lies with political integration with the rest of India and economic integration with the rest of Asia and Oceania, with North, East and Southeast Asia, Micronesia and Polynesia in particular, as the policy of economic integration with the rest of India did not yield much dividends. With the development of this new policy, the Government of India directed its Look East policy towards developing the Northeastern region. This policy is reflected in the Year End Review 2004 of the Ministry of External Affairs, which stated that: "India’s Look East Policy has now been given a new dimension by the UPA Government. India is now looking towards a partnership with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN countries, both within BIMSTEC and the India-ASEAN Summit dialogue as integrally linked to economic and security interests, particularly for India’s East and North East region."[126]

Development and connectivity projects

editThe north-east (NE) region of India lags behind the rest of the country in several development indicators. Although infrastructure has developed over the years, the region has to go a long way to level up the national standard. The total road network of about 377 thousand km of NE contributes about 9.94 per cent of the total roads in the country. Road density in terms of road length per thousand square kilometres. area is very poor in hilly state of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Sikkim, while it is significantly high in Tripura and Assam. The road length per 100 km2 area in NE districts varies from as less as below 10 km (in Arunachal Pradesh) to more than 200 km (in Tripura). Other means of transport such as rail, air and water is insignificant in NE (except Assam); however, a few cities of these states having direct air connectivity in the region. The total railway network in the NE is 2,602 km (as on 2011), which is only about 4 per cent of the total rail network of the country. Constructions of roads build the road map for development and road is the only means of mass transport for the entire NE of India. Due to hilly terrain and varied altitudes, rail transport is mainly confined to Assam and water transport is almost non-existent.

India's road network has benefited greatly from the articulation of the National Highways Development Project (NHDP). The Ministry has formulated the Special Accelerated Road Development Programme for North East (SARDP-NE) for the development/improvement of more than 10,000 km roads in the NE states. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) has been paying special attention to the development of national highways in the region and has assigned 10 per cent of the total allocation of fund for the NE region.

Another major constraint of surface infrastructure projects in the NE states has to be linked up with parallel developments in the neighbouring countries, particularly with Bangladesh. The restoration and extension of pre-partition land and river transit routes through Bangladesh is vital for transport infrastructure in NE states. Other international cooperation, such as, revival of Ledo road (Stilwell road) connecting Ledo in Assam to northern Myanmar and extended up to Kunming in south-eastern China, Kaladan Multimodal Transit Project and Trans-Asian Railways, could open up an eastern window for the land-locked NE states of India. Various regional initiatives, such as, the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) and Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway (IMTTH) project to link the markets of South and Southeast Asia, are in very initial stages.[127]

See also

edit- Battle of the Tennis Court

- Laskar Committee Report

- Ledo Road (Stillwell Road)

- List of Christian denominations in Northeast India

- Literature from North East India

- Political integration of India

- History of Ladakh

- List of indigenous peoples of South Asia

- East India

- North India

- South India

- Central India

- Western India

- Administrative divisions of India

- Northeastern South Asia

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "Indian cities by population" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "State/UT wise Aadhaar Saturation" (PDF). Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Languages Included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution | Department of Official Language | Ministry of Home Affairs | GoI". rajbhasha.gov.in. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Manipuri language | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 84–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Nath, Monoj Kumar (29 March 2021). The Muslim Question in Assam and Northeast India. Taylor & Francis. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-000-37027-0.

- ^ a b Chakravarti, Sudeep (6 January 2022). The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India's Far East. Simon and Schuster. p. 421. ISBN 978-93-92099-26-7.

- ^ a b Kumāra, Braja Bihārī (2007). Problems of Ethnicity in the North-East India. Concept Publishing Company. p. 88. ISBN 978-81-8069-464-6.

- ^ Wadley, Susan S. (18 December 2014). South Asia in the World: An Introduction: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-317-45959-0.

- ^ Oinam, Bhagat; Sadokpam, Dhiren A. (11 May 2018). Northeast India: A Reader. Taylor & Francis. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-429-95320-0.

- ^ Deb, Bimal J. (2006). Ethnic Issues, Secularism, and Conflict Resolution in North East Asia. Concept Publishing Company. p. 21. ISBN 978-81-8069-134-8.

- ^ a b Britannica. Student Britannica India 7 Vols. Popular Prakashan. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-85229-762-9.

- ^ Brenzinger, Matthias (31 July 2015). Language Diversity Endangered. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 322. ISBN 978-3-11-090569-4.

- ^ Experts, Arihant (4 June 2019). General Knowledge 2020. Arihant Publications India limited. p. 531. ISBN 978-93-131-9167-4.

- ^ a b Purkayastha, Biswa Kalyan (24 February 2024). "Assam recognises Manipuri as associate official language in four districts". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ PTI (24 February 2024). "Assam Cabinet gives nod to recognise Manipuri as associate official language in four districts". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Legislative assembly". Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Home ,Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region, North East India". mdoner.gov.in. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b "North Eastern Council". Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Problems of border areas in Northeast India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Integration of Sikkim in North Eastern Council". The Times of India. 10 December 2002. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Evaluation of NEC funded projects in Sikkim" (PDF). NEC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Geography of Assam. New Delhi: Rajesh Publications. 2001. p. 12. ISBN 81-85891-41-9. OCLC 47208764. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

The first group of migrants to settle in this part of the country is perhaps the Austro-Asiatic language speaking people who came here from South-East Asia a few millennia before Christ. The second group of migrants came to Assam from the north, north-east and east. They are mostly the Tibeto-Burman language speaking people. From about the fifth century before Christ, there started a trickle of migration of the people speaking Indo-Aryan language from the Gangetic plain.

- ^ Hazarika, M. 2006 "Neolithic Culture of Northeast India: A Recent Perspective on the Origins of Pottery and Agriculture". Ancient Asia, 1, doi:10.5334/aa.06104

- ^ "Chang K'ien had clearly realized the existence of a trade route between Sichuan and India via Yunnan and Burma or Assam" (Lahiri 1991, pp. 11–12)

- ^ Besatae in the Schoff translation and also sometimes used by Ptolemy, they are a people similar to Kirradai and they lived in the region between "Assam and Sichuan" (Casson 1989, pp. 214–242)

- ^ (Casson 1989, pp. 51–53)

- ^ "The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea (last quarter of the first century A.D) and Ptolemy's Geography (middle of the second century A.D) appear to call the land including Assam Kirrhadia after its Kirata population." (Sircar 1990:60–61)

- ^ (Watters 1905, p. 186)

- ^ Baruah, Sanjib (2004), Between South and Southeast Asia Northeast India and Look East Policy, Ceniseas Paper 4, Guwahati

- ^ May, Andrew (2015). Welsh Missionaries and British Imperialism: The Empire of Clouds in North-east India. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719099977.

- ^ a b (Guha 1977, p. 2)

- ^ "Formation of Assam during British rule in India". Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Formation of North Eastern states from Assam". Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Shillong becomes the capital of Meghalaya". Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "The North Eastern Areas (Re-organisation Act) 1971" (PDF). meglaw.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Ancient name of Manipur". 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Historical evolution of Mizoram" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "History of Mizoram". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Ranjan Pal (4 October 2020). "Revisiting India's forgotten battle of WWII: Kohima–Imphal, the Stalingrad of the East". CNN. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "Battles of Imphal and Kohima | National Army Museum". National Army Museum. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Kohima: Britain's 'forgotten' battle that changed the course of WWII". 14 February 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Remembering The Second World War in North East India". The India Forum. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Guyot-Réchard, Bérénice (2018). "When Legions Thunder Past: The Second World War and India's Northeastern Frontier". War in History. 25 (3): 328–360. doi:10.1177/0968344516679041. ISSN 0968-3445. JSTOR 26500618.

- ^ "China says Arunachal Pradesh part of it "since ancient times"". The Economic Times. PTI. 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ Larry M. Wortzel, Robin D. S. Higham (1999), Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese Military History

- ^ Saikia, J. P (1976). The Land of seven sisters. Place of publication not identified: Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Assam. OCLC 4136888.

- ^ "Who are the Seven Sisters of India?". HT School. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ Dikshit 2014, p. 150.

- ^ Dikshit 2014, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dikshit 2014, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Dikshit 2014, p. 149.

- ^ a b Dikshit 2014, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d e Dikshit 2014, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "JetStream Max: Addition Köppen-Geiger Climate Subdivisions". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Dikshit 2014, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e Dikshit 2014, p. 156.

- ^ a b Dikshit 2014, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Dikshit 2014, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Dikshit 2014, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d Dikshit 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Dikshit 2014, p. 59.

- ^ "At least eight dead as north-east India hit by 6.7 magnitude earthquake". The Guardian. 4 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ J. R. Kayal; S. S. Arefiev; S. Barua; Devajit Hazarika; N. Gogoi; A. Kumar; S. N. Chowdhury; Sarbeswar Kalita (July 2006). "Shillong Plateau Earthquakes". Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Hedge 2000, FSI 2003.

- ^ Saikia, Parth (15 May 2020). "Biodiversity of Northeast India | Flora, Fauna and Hotspots". North East India Info. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Kaziranga National Park – a world heritage site, Govt. of Assam" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Khangchendzonga National Park". Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "A note on non-human primates of Murlen National Park, Mizoram, India" (PDF). Zoological Survey of India. 106 (Part-1): 111–114. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Orang Tiger Reserve". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Forest types of Mizoram". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Nagaland records negative decadal growth". The Hindu. April 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ (Moral 1997, p. 42)

- ^ "IITG – Hierarchy of North Eastern Languages". Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ (Moral 1997, pp. 43–44)

- ^ Blench, R. & Post, M. W. (2013). Rethinking Sino-Tibetan phylogeny from the perspective of Northeast Indian languages Archived 26 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Post, M. W. and R. Burling (2017). The Tibeto-Burman languages of Northeast India Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Language – India, States and Union Territories" (PDF). Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General. pp. 13–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue". census.gov.in. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Banerjee, Paula (2008). Women in Peace Politics. Sage. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7619-3570-4.

- ^ "Report on North East India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Govt withdraws Assamese as official language from Barak valley". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 9 September 2014. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Nagaland State Profile". Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Know Tripura | Tripura State Portal". tripura.gov.in. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Ahoms also gave Assam and its language their name (Ahom and the modern ɒχɒm. 'Assam' comes from an attested earlier form asam, acam, probably from a Burmese corruption of the word Shan/Shyam, cf. Siam: Kakati 1962; 1–4)." (Masica 1993, p. 50)

- ^ "India - C-01: Population by religious community, India - 2011". censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Population By Religious Community". Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Tribal groups in Assam and Northeast India". Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ van Driem, G. (2012)

- ^ a b Bihar, Ghata (30 May 2023). "Northeast India craft forms – biharghata.in". Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Arunachal Pradesh". Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Arts and crafts of North-east India". Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Popular dances of Meghalaya". Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Meghalaya handicrafts". Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Dances in Mizoram". Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Mizoram handicrafts". Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Sikkim dances". Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "Culture of Sikkim – sikkimonline.in". Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Folk dances of Sikkim". Bihar Gatha. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Sundaresan, Eshwar (20 October 2022). "Music a language in itself in north-east India". Frontline. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Jnanpith | Laureates". jnanpith.net. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Assamese, Manipuri, Naga authors have kept alive World War II fought 70 years ago". The Indian Express. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "..:: SAHITYA : Fellows and Honorary Fellows ::." sahitya-akademi.gov.in. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Press release, election of fellows of Sahitya Akademy" (PDF). Sahitya Akademi. 29 January 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "..:: SAHITYA : Akademi Awards ::." sahitya-akademi.gov.in. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Sadangi 2008, p. 48–55.

- ^ "A Culture Of Sports Brings Northeast Closer To India". Outlook India. 9 August 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "'The Only Real Game' Explores Baseball's Long History in India's Manipur". Newsweek. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Autonomous District Councils of Manipur". Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Manipur District Council Act 1971". 22 February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ http://india.gov.in/my-governmentra/whos-who/chief-ministers [dead link]

- ^ "Governors | National Portal of India". Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Seventh Kamal Kumari Memorial Lecture". Archived from the original on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- ^ "11 rebel groups call for Republic Day boycott". The Times of India. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "NE rebels call general strike on I-Day". The Sangai Express. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "Living Root Bridges". Cherrapunjee. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Living Root Bridge Project". The Living Root Bridge Project. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Living-Root Bridge: The Symbol of Benevolence". Riluk. 10 October 2016. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Why is Meghalaya's Botanical Architecture Disappearing?". The Living Root Bridge Project. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Living Root Bridges of Nagaland India – Nyahnyu Village Mon District | Guy Shachar". guyshachar.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ By March 2023, Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland to have rail connectivity Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Business Standard, 29 August 2020.

- ^ Sachdeva, Gulshan. Economy of the North-East: Policy, Present Conditions and Future Possibilities. New Delhi: Konark Publishers, 2000, p. 145.

- ^ Thongkholal Haokip, India’s Northeast Policy: Continuity and Change Archived 28 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Man and Society – A Journal of North-East Studies, Vol. VII, Winter 2010, pp. 86–99.

- ^ Year End Review 2004, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. New Delhi.

- ^ Nandy, S.N. (2014). "Road Infrastructure in Economically Underdeveloped North-east India". Journal of Infrastructure Development. 6 (2): 131–144. doi:10.1177/0974930614564648. S2CID 155649407.

Sources cited

edit- Guha, Amalendu (1977). Planter-raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam, 1826-1947. Indian Council of Historical Research: People's Publishing House. ISBN 8189487035.

- Casson, Lionel (1989). The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text With Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04060-8.

- Sircar, D C (1990), "Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, vol. I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 59–78

- Dikshit, K.; Dikshit, Jutta (2014). "Weather and Climate of North-East India". North-East India: Land, People and Economy. Advances in Asian Human-Environmental Research. Springer Netherlands. pp. 149–173. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7055-3_6. ISBN 978-94-007-7054-6.

- Grierson, George A. (1967) [1903]. "Assamese". Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. V, Indo-Aryan family. Eastern group. New Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass. pp. 393–398.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (1991). Pre-Ahom Assam: Studies in the Inscriptions of Assam between the Fifth and the Thirteenth Centuries AD. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd.

- Masica, Colin P. (1993), Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521299442, archived from the original on 26 July 2020, retrieved 26 September 2017

- Moral, Dipankar (1997), "North-East India as a Linguistic Area" (PDF), Mon-Khmer Studies, 27: 43–53, archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021, retrieved 19 December 2020

- Sharma, Benudhar, ed. (1972), An Account of Assam, Gauhati: Assam Jyoti

- Taher, M (2001), "Assam: An Introduction", in Bhagawati, A K (ed.), Geography of Assam, New Delhi: Rajesh Publications, pp. 1–17

- Watters, Thomas (1905). Davids, T. W. Rhys; Bushell, S. W. (eds.). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India. Vol. 2. London: Royal Asiatic Society. ISBN 9780524026779. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- Nandy, S N (2014), "Agro-Economic Indicators—A Comparative Study of North-Eastern States of India", Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 2: 75–88, doi:10.1177/2321024913515127, S2CID 128485864

- van Driem, George (2012), ""Glimpses of the Ethnolinguistic Prehistory of Northeastern India".", in Huber, Toni (ed.), Origins and Migrations in the Extended Eastern Himalayas, Leiden: Brill

- Sadangi, H. C. (2008). Emergent North-East: A Way Forward. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 9788182054370.

External links

edit- Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region

- Know India/States

- Northeast India Tourism Archived 2 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Northeast India travel guide from Wikivoyage