Francis Joseph Hardy (21 March 1917 – 28 January 1994), published as Frank J. Hardy and also under the pseudonym Ross Franklyn, was an Australian novelist and writer. He is best known for his 1950 novel Power Without Glory, and for his later political activism. He brought the plight of Aboriginal Australians to international attention with the publication of his book, The Unlucky Australians, in 1968, written during the Gurindji Strike. He ran unsuccessfully for the Australian parliament twice as a Communist Party of Australia candidate.

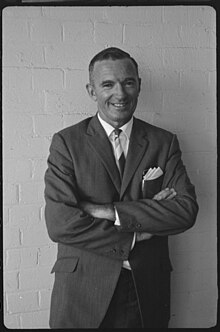

Frank Hardy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Francis Joseph Hardy 21 March 1917 Southern Cross, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 28 January 1994 (aged 76) Carlton North, Australia |

| Resting place | Fawkner Memorial Park |

| Pen name | Ross Franklin |

| Occupation | Author |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Citizenship | Australian |

| Period | 1950-1992 |

| Literary movement | left wing political |

| Notable works | Power Without Glory |

| Spouse | Rosslyn Couper |

| Children | Frances, Alan and Shirley |

| Relatives | Sister, Mary Hardy, granddaughter Marieke Hardy |

Early life

editFrank Hardy, the fifth of the eight children of Thomas and Winifred Hardy, was born on 21 March 1917 at Southern Cross in Western Victoria and later moved with his family to Bacchus Marsh, west of Melbourne.[1][2][3] His mother, Winifred, was a Roman Catholic – his father, Thomas, an atheist of Welsh and English descent. In 1931 Hardy left school, aged 14, and embarked upon a series of manual jobs. According to Hardy biographer Pauline Armstrong, "his first job was as a messenger and bottlewasher at the local chemist's shop" and then Hardy worked at the local grocer. He later also did manual work "in and around Bacchus Marsh in the milk factory, digging potatoes, picking tomatoes and fruit".[citation needed]

There is some debate among Hardy's biographers about the relative extent Hardy personally suffered from hardships during the 1930s depression. Hardy claimed himself that he left home when he was 13 because "his dad couldn't get the dole" with him at home.[4] However, Jim Hardy, Frank's eldest brother, wrote to the Melbourne Herald on 6 November 1983 to rebut this assertion, claiming that Frank had never had to leave home – further noting that their "father never lost a day's work in his life". According to biographer Jenny Hocking[1] in a more recent biography, Tom Hardy did indeed lose his job at a milk factory at the start of the Great Depression, and the family had to move into a small rented house in Lerderderg Street.

In 1937, Radio Times published a selection of his cartoons.[citation needed]

Adult life

editIn 1940, Hardy married Rosslyn Couper and they had three children, Frances, Alan and Shirley. From 1954 they made their home in Sydney.[citation needed]

Communist Party of Australia

editBecause of his experiences during the Depression, Hardy joined the Communist Party of Australia in 1939. Hardy stood unsuccessfully twice as a CPA candidate for public office: in 1953 as a Senate candidate for Victoria, and in 1955 for the seat of Mackellar (NSW) in the House of Representatives.

Hardy also stood unsuccessfully for the National Committee of the CPA in 1955 and again in 1967.

Australian Army service

editHardy was called up for army service and became a member the Citizen Military Force on 22 April 1942. He spent more than a year based in the Melbourne area, first with the Area Staff of the 3rd Military District and then as a clerk and draughtsman with the Australian Army Ordnance Corps. In June 1943 he transferred to the Second Australian Imperial Force and in July was posted to Mataranka in the Northern Territory with the 7th Advanced Ordnance Depot. He later transferred to the 8th Advanced Ordnance Depot and edited the unit newspaper, the Troppo Tribune. In November 1944, he was transferred again be an artist for the army journal, Salt. He was discharged on 26 February 1945.[5][6]

After his discharge, his short stories "A Stranger in the Camp" and "The Man from Clinkapella" won competitions, and his work was accepted by Coast to Coast and The Guardian. Many of his early stories were written under the pseudonym Ross Franklyn.

Journalism

editHe continued to work in journalism for most of his life. Although he opposed the foundation of the Australian Society of Authors for political reasons in 1963, he later joined the Society and served on its Management Committee. He played an active role in assisting the Gurindji people in the Gurindji strike in the mid to late 1960s.[7] The documentary film The Unlucky Australians, which featured Frank Hardy and the Gurindji people, was made by director and producer John Goldschmidt for Associated Television (ATV) and transmitted on the ITV network in the UK.

Power Without Glory

editHis most famous work, Power Without Glory, was initially published in 1950 by Hardy himself, with the assistance of other members of the Communist Party. The novel is a fictionalised version of the life of a Melbourne businessman, John Wren, and is set largely in the fictitious Melbourne suburb of Carringbush (based on the actual suburb Collingwood).

In 1950 Hardy was arrested for criminal libel and had to defend Power Without Glory in a celebrated case shortly after its publication. Prosecutors alleged that Power Without Glory criminally libelled John Wren's wife by implying that she had engaged in an extramarital affair. Hardy was acquitted and it was the last criminal libel case launched in Victoria; all subsequent libel cases have been civil. Hardy detailed the case in his book The Hard Way.[8]

Power Without Glory was filmed by the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) in 1976 as a 26-episode television series adapted by Howard Griffiths and Cliff Green.

Following the success of Power Without Glory, Hardy founded the Australasian Book Society.[9]

The Unlucky Australians

editIn 1968, Hardy published The Unlucky Australians, with a foreword by Donald Horne and contributions by Vincent Lingiari, Aboriginal Union organiser Daniel Dexter, actor Robert Tudawali and others, telling the story of the Gurindji people based on personal narratives, and the Gurindji Strike.[10]

Plays

editHardy also wrote plays, including Who was Henry Larsen (first performed 1984) and Faces in the Street (first performed 1988, published 1990), which were both based on Henry Lawson.[citation needed]

Hardy founded the Realist Writers Group,[11] which he represented in 1951 at the 3rd World Festival of Youth and Students in Berlin.

Death

editFrank Hardy died at his home in North Carlton, a suburb of Melbourne, from a heart attack on 28 January 1994, aged 76. His cremated remains were interred at Fawkner Memorial Park.

Family

editHardy's younger sister, Mary Hardy, was a popular radio and television personality in the 1960s/1970s.[12]

His granddaughter, Marieke Hardy, is a writer in Melbourne.

Bibliography

edit- Power Without Glory, 1950. Reprint 2000 ISBN 0-522-84888-5

- Journey Into the Future, 1952

- The Four Legged Lottery 1958 ISBN 0-00-614501-9

- The Hard Way: The Story Behind Power without Glory, 1961. ISBN 0-00-614471-3

- Legends from Benson's Valley, 1963. ISBN 0-14-007504-6

- The Yarns of Billy Borker, 1965.

- Billy Borker Yarns Again, 1967.

- The Unlucky Australians, 1968. 1972 ISBN 0-7260-0012-4

- Outcasts of Foolgarah, 1971, ISBN 0-85887-000-2

- But the Dead Are Many: A Novel in Fugue Form, 1975, ISBN 0-370-10570-2

- The Needy and the Greedy: Humorous Stories of the Racetrack, 1975.

- The Obsession of Oscar Oswald, 1983, ISBN 0-9592104-1-5

- Who Shot George Kirkland? : A Novel About the Nature of Truth, 1981.

- Warrant of Distress, 1983, ISBN 978-0-9592104-2-2

- The Loser Now Will Be Later to Win, 1985.

- Mary Lives!, 1992 ISBN 0-86819-350-X .

Books about Frank Hardy

edit- Frank Hardy: Politics, Literature, Life, Jenny Hocking (South Melbourne: Lothian Books, 2005, ISBN 0-7344-0836-6)

- Frank Hardy and the Literature of Commitment Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, edited by Paul Adams & Christopher Lee (North Carlton, Victoria: The Vulgar Press, 2003, ISBN 0-9580-7941-2)

- Frank Hardy and the Making of Power without Glory, Pauline Armstrong (Carlton South: Melbourne University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-522-84888-5)

- The Stranger From Melbourne: Frank Hardy – A Literary Biography 1944 – 1975, Paul Adams (University of Western Australia Press, 1999, ISBN 1-876268-23-9)

References

edit- ^ a b Hocking, Jenny. Frank Hardy: Politics, Literature, Life South Melbourne: Lothian Books: 2005; ISBN 0-7344-0836-6

- ^ Armstrong, Pauline. Frank Hardy and the Making of Power Without Glory. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84888-5

- ^ Adams, Paul. The Stranger From Melbourne: Frank Hardy – A Literary Biography 1944–1975. University of Western Australia Press: 1999; ISBN 1-876268-23-9

- ^ See interview "Hardy declares war on poverty" in The Herald (Melbourne) of 7 October 1983

- ^ Military service record, B883, VX126476, National Archives of Australia, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=6081665&S=6&R=0

- ^ Paul Adams, "Hardy, Francis Joseph (Frank), Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hardy-francis-joseph-frank-19531

- ^ Jennett, Christine (Summer 2015–2016). "Big Things Grow". SL Magazine. 8 (4): 17.

- ^ "The Hard Way : The Story Behind Power Without Glory". AustLit: Discover Australian Stories. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ McLaren, John (1996). Writing in Hope and Fear: Literature as Politics in Postwar Australia. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780521567565.

- ^ Hardy, Frank (Francis Joseph) (1968). The Unlucky Australians. Nelson (Australia). Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ McLaren, John (1986). "A failed vision : Realist Writers' Groups in Australia, 1945-65 : the case of Overland". VU Research Repository | Victoria University | Melbourne Australia. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ Knox, David (6 February 2008). "Mary Hardy, the tragic clown". Retrieved 6 July 2009.