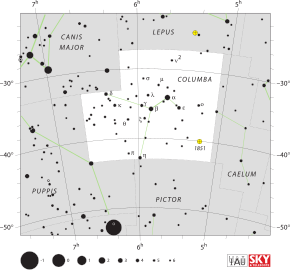

Columba is a faint constellation designated in the late sixteenth century, remaining in official use, with its rigid limits set in the 20th century. Its name is Latin for dove. It takes up 1.31% of the southern celestial hemisphere and is just south of Canis Major and Lepus.

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Col |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Columbae |

| Pronunciation | /kəˈlʌmbə/, genitive /kəˈlʌmbiː/ |

| Symbolism | the dove |

| Right ascension | 05h 03m 53.8665s–06h 39m 36.9263s[1] |

| Declination | −27.0772038°–−43.1116486°[1] |

| Area | 270 sq. deg. (54th) |

| Main stars | 5 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 18 |

| Stars with planets | 1 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 1 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | α Col (Phact) (2.65m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | 0 |

| Bordering constellations | Lepus Caelum Pictor Puppis Canis Major |

| Visible at latitudes between +45° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of February. | |

History

edit- Early 3rd century BC: Aratus's astronomical poem Phainomena (lines 367–370 and 384–385) mentions faint stars where Columba is now but does not fit any name or figure to them.

- 2nd century AD: Ptolemy listed 48 constellations in the Almagest but did not mention Columba.

- c. 150–215 AD: Clement of Alexandria wrote in his Logos Paidogogos[2]"Αἱ δὲ σφραγῖδες ἡμῖν ἔστων πελειὰς ἢ ἰχθὺς ἢ ναῦς οὐριοδρομοῦσα ἢ λύρα μουσική, ᾗ κέχρηται Πολυκράτης, ἢ ἄγκυρα ναυτική," (= "[when recommending symbols for Christians to use], let our seals be a dove or a fish or a ship running in a good wind or a musical lyre ... or a ship's anchor ..."), with no mention of stars or astronomy.

- 1592 AD: [3] Petrus Plancius first depicted Columba on the small celestial planispheres of his large wall map to differentiate the 'unformed stars' of the large constellation Canis Major.[4] Columba is also shown on his smaller world map of 1594 and on early Dutch celestial globes. Plancius named the constellation Columba Noachi ("Noah's Dove"), referring to the dove that gave Noah the information that the Great Flood was receding. This name is found on early 17th-century celestial globes and star atlases.

- 1592: Frederick de Houtman listed Columba as "De Duyve med den Olijftack" (= "the dove with the olive branch")

- 1603: Bayer's Uranometria was published. It includes Columba as Columba Noachi.[5]

- 1624: Bartschius listed Columba in his Usus Astronomicus as "Columba Nohae".

- 1662: Caesius published Coelum Astronomico-Poeticum, including an inaccurate Latin translation of the above text of Clement of Alexandria: it mistranslated "ναῦς οὐριοδρομοῦσα" as Latin "Navis coelestis cursu in coelum tendens" ("Ship of the sky following a course in the sky"), perhaps misunderstanding "οὐριο-" as "up in the air or sky" by analogy with οὐρανός = "sky".

- 1679: Halley mentioned Columba in his work Catalogus Stellarum Australium from his observations on St. Helena.

- 1679: Augustin Royer published a star atlas that showed Columba as a constellation.

- c.1690: Hevelius's Prodromus Astronomiae showed Columba but did not list it as a constellation.

- 1712 (pirated) and 1725 (authorized): Flamsteed's work Historia Coelestis Britannica showed Columba but did not list it as a constellation.

- 1757 or 1763: Lacaille listed Columba as a constellation and catalogued its stars.

- 1889: Richard H. Allen,[6] misled by Caesius's mistranslation, wrote that the Columba asterism may have been invented in Roman/Greek times, but with a footnote saying that it may have been another star group.

- 2001: Ridpath and Tirion wrote that Columba may also represent the dove released by Jason and the Argonauts at the Black Sea's mouth; it helped them navigate the dangerous Symplegades.[3]

- 2007: The author P.K. Chen wrote (his opinion) that, given the mythological linkage of a dove with Jason and the Argonauts, and the celestial location of Columba over Puppis (part of the old constellation Argo Navis, the ship of the Argonauts), Columba may have an ancient history although Ptolemy omits it.[7][8]

- 2019–20: OSIRIS-REx students discovered a black hole in the constellation Columba, based on observing X-ray bursts.[9]

In the Society Islands, Alpha Columbae (Phact) was called Ana-iva.[10]

Features

editStars

editColumba is rather inconspicuous, the brightest star, Alpha Columbae, being only of magnitude 2.7. This, a blue-white star, has a pre-Bayer, traditional, Arabic name Phact (meaning ring dove) and is 268 light-years from Earth. The only other named star is Beta Columbae, which has the alike-status name Wazn. It is an orange-hued giant star of magnitude 3.1, 87 light-years away.[11]

The constellation contains the runaway star μ Columbae, which was probably expelled from the ι Orionis system.

Exoplanet NGTS-1b and its star NGTS-1 are in Columba.

General radial velocity

editColumba contains the solar antapex – the opposite to the net direction of the solar system[12] (noting the local spiral arm of the Milky Way itself is responsible for most of our change of position over time).[citation needed]

Deep-sky objects

editNGC 1851 a globular cluster in Columba appears at 7th magnitude in a far part of our galaxy as is 39,000 light-years away - it is resolvable south of at greatest latitude +40°N in medium-sized amateur telescopes (under good conditions).[11]

- NGC 1792 is a spiral galaxy of magnitude 10.2.

- NGC 1808 is a Seyfert galaxy of magnitude 10.8.

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ a b "Columba, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ B. Schildgen (2016). Heritage or Heresy: Preservation and Destruction of Religious Art and Architecture in Europe. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-230-61315-7.

- ^ a b Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Ley, Willy (December 1963). "The Names of the Constellations". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 90–99.

- ^ Canis Maior and Columba in Bayers Uranometria 1603 (Linda Hall Library) Archived 2007-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Richard H. Allen (1899) Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, pp. 166–168

- ^ P.K. Chen (2007) A Constellation Album: Stars and Mythology of the Night Sky, p. 126 (ISBN 978-1-931559-38-6).

- ^ Chen, p. 126.

- ^ "NASA's OSIRIS-REx Students Catch Unexpected Glimpse of Newly Discovered Black Hole". NASA. 28 February 2020.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 281.

- ^ a b Ridpath & Tirion 2017, p. 122.

- ^ Madore, Barry F. (14 August 2002). "Astronomical Glossary". NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

References

edit- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press. p. 281. Bibcode:1941msra.book.....M.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017). Stars and planets guide (Fifth ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-823927-5. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-69-117788-5.

External links

edit- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Columba

- The clickable Columba

- Star Tales – Columba

- Lost Stars, by Morton Wagman, publ. Mcdonald & Woodward Publishing Company, First printing September 2003, ISBN 0-939923-78-5 , page 110