Prada

Logo since 2002 | |

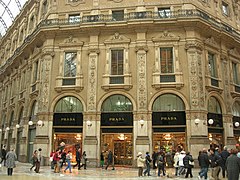

Prada boutique at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Italy | |

| Company type | Public (S.p.A.) |

|---|---|

| SEHK: 1913 | |

| Industry | Fashion |

| Founded | 1913 (as Fratelli Prada) |

| Founder | Mario Prada (nee Pappradda) |

| Headquarters |

|

Number of locations | 606 boutiques[1] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Andrea Guerra (CEO) Miuccia Prada (head designer) Patrizio Bertelli (chairman)[2] |

| Products | Luxury goods |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 14,876 (2023)[1] |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | prada.com |

Prada S.p.A. (/ˈprɑːdə/ , PRAH-də; Italian: [ˈpraːda]) is an Italian luxury fashion house founded in 1913 in Milan by Mario Prada. It specializes in leather handbags, travel accessories, shoes, ready-to-wear, and other fashion accessories. Prada licenses its name and branding to Luxottica for eyewear[3] and L’Oréal for fragrances and cosmetics.[4]

Founded in 1913 and named for the family of founder Mario Prada, the company originally sold imported English animal goods before transitioning to waterproof nylon fabrics in the 1970s under the leadership of Mario's granddaughter, Miuccia Prada and her husband Patrizio Bertelli. By the 1990s, Prada was perceived as a luxury brand, a designation credited to originality in its designs. To further the business, Miuccia Prada founded Miu Miu as a subsidiary of Prada around this time period; the company additionally partnered with LVMH to acquire a joint stake in Fendi; Prada further assisted LVMH in its failed takeover of Gucci.

The brand struggled through the late 2000s and early to mid 2010s, which included a failed initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, though began a resurgence in popularity entering into the 2020s. Miuccia Prada and Bertelli, both entering old age, began a transition in leadership to their children in the 2020s, bringing in former Luxottica CEO Andrea Guerra to lead the company for the years during the transition. The house presently sees annual revenue in the billions of Euros, making €4.2 billion in 2022 with profit that same year totaling to €776 million; furthermore, Prada and less so Miu Miu are seen as having very high desirability among consumers across various reports.[5][6][7]

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]

The company started in 1913 by Mario Prada and his brother Martino as Fratelli Prada, a leather goods shop in Milan.[8][9] Initially, the shop sold animal goods, imported English steamer trunks, handbags. Alongside these handcrafted leather goods, Prada also sold travel accessories,[10] as well as beauty cases, jewelry, luxury items, and rare objects.[11]

Mario Prada opens an exclusive store in Milan’s prestigious Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II that sells leather bags, trunks, beauty cases, jewels, luxury accessories, and rare objects.

Mario Prada did not believe women should have a role in business, so he prevented female family members from entering his company. Ironically, Mario's son had no interest in the business,[12] so it was Mario's daughter Luisa who succeeded Mario and ran Prada for almost twenty years. Luisa's daughter, Miuccia Prada, joined the company in 1970, eventually taking over from Luisa in 1978.[13]

Miuccia began making waterproof backpacks out of Pocono, a nylon fabric.[8] She met Patrizio Bertelli in 1977, an Italian who had begun his own leather goods business at the age of 24, and he joined the company soon after. He advised Miuccia on company business, which she followed.[13] It was his advice to discontinue importing English goods and to change the existing luggage.[citation needed]

Development

[edit]Miuccia inherited the company in 1978 by which time sales were up to U.S. $450,000. With Bertelli alongside her as business manager, Miuccia was allowed time to implement her creativity in the company's designs.[8] She would go on to incorporate her ideas into the house of Prada that would change it.[8]

She released her first set of backpacks and totes in 1979. They were made out of a tough military spec black nylon that her grandfather had used as coverings for steamer trunks. Initial success was not instant, as they were hard to sell due to the lack of advertising and high prices, but the lines would go on to become her first commercial hit.[13]

Next, Miuccia and Bertelli sought out wholesale accounts for the bags in upscale department stores and boutiques worldwide. In 1983, Prada opened a second boutique in the centre of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan's shopping heart, on the site of the previous historic "London House" emporium run by Felice Bellini from 1870 to the 1960s, reminiscent of the original shop, but with a sleek and modern contrast to it.[citation needed]

The next big release was a nylon tote. That same year, the house of Prada began expansion across continental Europe and the United States by opening locations in prominent shopping districts within Florence, Paris, Madrid, and New York City. A shoe line was also released in 1984. In 1985 Miuccia released the "classic Prada handbag" that became an overnight sensation. Although practical and sturdy, its sleek lines and craftsmanship had a luxury that has become the Prada signature.[14]

In 1987, Miuccia and Bertelli married. Prada launched its women's ready-to-wear collection in 1988, and the designs came to be known for their dropped waistlines and narrow belts. Prada's popularity increased when the fashion world took notice of its clean lines, opulent fabrics, and basic colors.[13]

The logo for the label was not as obvious a design element as those on bags from other prominent luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton. It tried to market its lack of prestigious appeal, including of its apparel, by projecting an image of "anti-status" or "inverse snobbery".[citation needed]

1990s

[edit]Prada's originality made it one of the most influential fashion houses,[8] and the brand became a premium status symbol in the 1990s.

Sales were reported at L 70 billion, or US$31.7 million, in 1998.[citation needed] Patrizio di Marco took charge of the growing business in the United States after working for the house in Asia. He was successful in having the Prada bags prominently displayed in department stores, so that they could become a hit with fashion editors. Prada's continued success was attributed to its "working-class" theme which, Ginia Bellafante at The New York Times Magazine proclaimed, "was becoming chic in the high-tech, IPO-driven early 1990s." Furthermore, now husband and wife, Miuccia and Bertelli led the Prada label on a cautious expansion, making products hard to come by.

In 1992, the high fashion brand Miu Miu, named after Miuccia's nickname, launched. Miu Miu catered to younger consumers and celebrities. By 1993 Prada was awarded the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) award for accessories.[8]

The first ready-to-wear menswear collection was Spring/Summer 1998.[15] By 1994, sales were at US$210 million, with clothing sales accounting for 20% (expected to double in 1995). Prada won another award from the CFDA, in 1995 as a "designer of the year" 1996 witnessed the opening of the 18,000 ft² Prada boutique in Manhattan, New York, the largest in the chain at the time. By now the House of Prada operated in 40 locations worldwide, 20 of which were in Japan. The company owned eight factories and subcontracted work from 84 other manufacturers in Italy. Prada's and Bertelli's respective businesses were merged to create Prapar B.V. in 1996. The name, however, was later changed to Prada B.V., and Patrizio Bertelli was named Chief Executive Officer of the Prada luxury company.

1996 can also be seen as marking an important turning point in Prada's aesthetics, one that fueled the brand's worldwide reputation. Journalists praised Miuccia's development of an “ugly chic” style, which initially confused customers by offering blatantly unsexy outfits which then revealed to offer daring and original takes on the relationship between fashion and desire.[16] Since then Prada has been regarded as one of the most intelligent and conceptual designers.

In 1997, Prada posted revenue of US$674 million. Another store in Milan opened that same year. According to The Wall Street Journal, Bertelli smashed the windows of the store a day before the opening, after he had become deeply unsatisfied with the set-up. Bertelli also acquired shares in the Gucci group, and later blamed Gucci for "aping his wife's designs." In June 1998, Bertelli gained 9.5% return on investment at US$260 million.[17] Analysts began to speculate that he was attempting a take over of the Gucci group. The proposition seemed unlikely, however, because Prada was at the time still a small company and was in debt. Funding Universe states that "At the very least, Prada had a voice as one of Gucci's largest shareholders (a 10 percent holding would be required for the right to request a seat on the board) and would stand to profit tidily should anyone try to take over Gucci." However, Bertelli sold his shares to Moët-Hennessy • Louis Vuitton chairman Bernard Arnault in January 1998 for a profit of US$140 million. Arnault was in fact attempting a take over of Gucci. LVMH had been purchasing fashion companies for a while and already owned Dior, Givenchy, and other luxury brands. Gucci, however, managed to fend him off by selling a 45% stake to industrialist François Pinault, for US$3 billion.[18] In 1998, the first Prada menswear boutique opened in Los Angeles.

Prada was determined to hold a leading portfolio of luxury brands, like the Gucci group and LVMH. Prada purchased 51% of Helmut Lang's company based in New York for US$40 million in March 1999.[19] Lang's company was worth about US$100 million. Months later, Prada paid US$105 million to have full control of Jil Sander A.G., a German-based company with annual revenue of US$100 million. The purchase gained Prada a foothold in Germany, and months later Jil Sander resigned as chairwoman of her namesake company. Church & Company, an English shoemaker, also came under the control of Prada, when Prada bought 83% of the company for US$170 million.[20] A joint venture between Prada and the De Rigo group was also formed that year to produce Prada eyewear. In October 1999, Prada joined with LVMH and beat Gucci to buy a 51% stake in the Rome-based Fendi S.p.A. Prada's share of the purchase (25.5%) was worth US$241.5 million out of the reported US$520 million total paid by both Prada and LVMH.[21][22] Prada took on debts of Fendi, as the latter company was not doing well financially.

These acquisitions elevated Prada to the top of the luxury goods market in Europe. Revenue tripled from that of 1996, to L2 trillion.[citation needed] Despite apparent success, the company was still in debt.

2000s

[edit]

The company's merger and purchasing sprees slowed in the 2000s. However, the company signed a loose agreement with Azzedine Alaia. Skincare products in unit doses were introduced in the United States, Japan, and Europe in 2000. A 30-day supply of cleansing lotion was marketed at the retail price of US$100. To help pay off debts of over US$850 million, the company planned on listing 30% of the company on the Milan Stock Exchange in June 2001. However, the offering slowed down after a decline in spending on luxury goods in the United States and Japan. In 2001, under the pressure of his bankers, Bertelli sold all of Prada's 25.5% share in Fendi to LVMH. The sale raised only US$295 million.

By 2006, the Helmut Lang, Amy Fairclough, Ghee, and Jil Sander labels were sold. Jil Sander was sold to the private equity firm Change Capital Partners, which was headed by Luc Vandevelde, the chairman of Carrefour, while the Helmut Lang label is now owned by Japanese fashion company Link Theory. Prada is still recovering from the Fendi debt. More recently, a 45% stake of the Church & Company brand has been sold to Equinox.

The Prada Spring/Summer 2009 Ready-to-Wear fashion show, held on 23 September 2008 in Milan, got infamous coverage because all the models on the catwalk were tottering[23] – several of them stumbled,[24] while two models fell down in front of the photographers and had to be helped by spectators to get up.[25] They removed their shoes in order to continue their walk.[26][27] One more model (Sigrid Agren) even had to stop and go back during the finale walk as she couldn't manage walking in her high heels any longer.[28] Interviewed right after the show, one model declared: "I was having a panic attack, my hands were shaking. The heels were so high."[29] The designer Miuccia Prada, on her side, did not blame the height of the shoes, but the silk little socks inside, which were slippery and moved inside of the shoes, preventing the models' feet from having a correct grip on the sole.[30][31] Miuccia Prada also assured that the shoes sold in stores would have a lower heel,[32] and that the little socks would be sewn into the shoes in order to prevent further slips. But many fashionistas rightly claimed that the socks, once sewn into the shoes, would be non-washable and would quickly stink and become grey.[33] Consequently, the shoes have never been commercially sold.

2010s

[edit]According to Fortune, Bertelli planned on increasing revenue of the company to US$5 billion by 2010.

On 6 May 2011 Hong Kong Stock Exchange came under fire for approving Prada's IPO despite the Prada Gender Discrimination Case. Feminist NGOs and Hong Kong Legislative Council lawmaker Lee Cheuk-yan protested in front of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.[34][35][36][37][38][39]

On 24 June 2011 the brand was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange to raise $2.14 billion, but failed to meet expectations reported by AAP on 17 June 2011[40] and Bloomberg.[41]

In 2015, Prada's turnover was 3,551.7 million euros, up 1 percent from 2014, while its gross operating profit fell 16.5 percent to 954.2 million euros.[42]

In July 2016, Prada began selling its clothing online through Net-a-Porter and Mytheresa in response to changing consumer preferences and the need to reach a wider audience. This strategic move allowed Prada to tap into e-commerce expertise, reduce overhead costs, and adapt to the digital age while maintaining its luxury brand image..[43]

As of March 2018, Prada's sales turned positive after declining since 2014, and their stock jumped 14% at the news.[44]

Stating that Prada would be "(f)ocusing on innovative materials will allow the company to explore new boundaries of creative design while meeting the demand for ethical products," the company announced in 2019 that fur will be eliminated from the collection and all house brands as of 2020.[45]

2020s

[edit]In February 2020, Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli named the Belgian designer Raf Simons as co-creative director.[46]

In August 2020, the fashion house announced it would no longer use kangaroo leather in its products.[47] In 2020, fashion magazine Vanity Teen promoted its Prada Resort 21 campaign.[48]

January 2023 saw Prada announce Andrea Guerra as its next CEO; Guerra formerly was CEO of both Luxottica and Eataly, and later the leader of LVMH's hotel division. Guerra was onboarded to ease the transition between the Bertelli and his children, who are expected to inherit the company. One of Guerra's first moves was to look at dual listing Prada stock on both the Hong Kong Stock Exchange as well as on a European stock exchange, expected to be one in Milan.[49][50]

Businesses today

[edit]Runway shows

[edit]Prada hosts seasonal runway shows on the international fashion calendar, taking place in Milan often at one of the brand's spaces.

1988 – first womenswear show in Milan

1998 – first menswear show in Milan[15]

Resort 2019 was shown in New York City at Prada's New York headquarters.[51] The show was broadcast over screens in Times Square.[52]

Previous Prada models include Daria Werbowy, Gemma Ward, Vanessa Axente, Suvi Koponen, Ali Stephens, Vlada Roslyakova and Sasha Pivovarova, who went on to appear in Prada's ad campaigns for six consecutive seasons after opening the Prada fall 2005 runway show. Prada has also featured many actors as models in their menswear shows and campaigns, including Gary Oldman, Adrien Brody, Emile Hirsch[53] and Norman Reedus.[54]

Prada's runway music is designed by Frédéric Sanchez.[55]

Boutiques

[edit]

Prada has commissioned architects, most notably Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron, to design flagship stores in various locations.

1913 – The original Prada store opened in Milan in inside the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II.[56]

1919 – Prada was appointed Official Supplier to the Italian Royal Household; as such, it incorporated the House of Savoy's coat of arms and knotted rope design into its logo.

1983 – Retail expansion sees a new boutique opened in Milan, as well as New York, Madrid, London, Paris, and Tokyo.

1991 – Further retail expansion and more boutiques open in New York City, China, and Japan.[57]

2001 – Broadway Epicenter in New York City by OMA opens.[58]

2003 – Tokyo Epicenter by Herzog & de Meuron[59] opens.[60]

2004 – Los Angeles Epicenter by OMA group opens.[61] Restored in 2012.

2008 – A duplex megastore was opened in Kuala Lumpur at the Pavilion Kuala Lumpur.

2009 – A new store focussing on the Prada Made to Order collection opened on Corso Venezia, Milan, designed by architect Robert Baciocchi.[62]

2012 – In June, Prada opened its largest ever boutique in Dubai's Mall of the Emirates.[63]

Other activities

[edit]Costume design

[edit]In 2007, Miuccia Prada contributed costume designs for two digital characters in the CGI film Appleseed Ex Machina.[64]

In 2010, Giuseppe Verdi’s Attila premiered at New York’s Metropolitan Opera with costumes by Miuccia Prada.[65]

In 2013, Miuccia Prada designed costumes for Baz Luhrmann's film The Great Gatsby in collaboration with costume designer Catherine Martin.[66]

Eyewear

[edit]2000 – Eyewear launched under Prada and Miu Miu labels, manufactured by Luxottica.[57]

Perfumes

[edit]2004 – Fragrance launched with the Puig company.[67] Women's fragrances were followed by men's fragrances in 2006. L'Oreal Group acquired the beauty license from Puig in 2021.[68]

- Exclusive Scents, 2003[69]

- Amber Woman, 2004[70]

- Amber Man, 2006[71]

- Infusion d'Iris, 2007[72]

- Infusion d'Homme, 2008[72]

- Luna Rossa, 2008

- Amber pour Homme Intense, 2011[73]

- Prada Candy, 2011[74]

- Prada Olfactories collection, 2015[75]

- Les Infusions de Prada, 2015[76]

- L'Homme and la Femme Prada, 2016[77]

- L'Homme and la Femme Prada Intense, 2017[78]

- La Femme Prada L'eau, 2017[79]

- Luna Rossa Ocean, 2021[80]

- Prada Paradoxe, 2022[81]

Cosmetics and Skincare

[edit]2023 – Launched through license with L'Oreal Luxe.[82] The color cosmetics are branded Prada Color, and the skincare line is branded Prada Skin. Initial product range included lipstick, foundation, eyeshadow, cleanser, moisturizer, and serum.[83]

Mobile phone

[edit]In May 2007, Prada began producing mobile phones with LG Electronics. Three mobile phones resulted from this collaboration: LG Prada (KE850), LG Prada II (KF900) and LG Prada 3.0. These devices were the origin of the current Smartphone.

Watches

[edit]Production of watches started in 2007 and was suspended in 2012. One of the watch models produced by Prada, the Prada Link, is compatible with bluetooth technology and can connect with the LG Prada II mobile phone.[84]

Spacesuits

[edit]In 2024, Axiom Space and Prada partnered to develop the Axiom Extravehicular Mobility Unit (AxEMU) spacesuit that will be used for NASA's Artemis III mission. [85]

Prada in popular culture

[edit]Films

[edit]The 1999 feature film 10 Things I Hate About You features the following exchange extolling the virtues of Prada ownership:[86]

Bianca: You know, there's a difference between like and love. I like my Skechers but I love my Prada backpack.

Chastity: But I love my Skechers.

Bianca: That’s because you don’t have a Prada backpack.

— 10 Things I Hate About You (1999)

The 2006 feature film The Devil Wears Prada (based on the 2003 book of the same name written by Lauren Weisberger) earned Meryl Streep an Oscar nomination for her role. Her shoe wardrobe for the film was said to be "at least 40% Prada" by the costume designer Patricia Field.[87] Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of American Vogue and the supposed inspiration for Meryl Streep's character, wore Prada to the film's premiere.[88]

Art

[edit]In 2005, a false Prada boutique was built as an art installation 26 miles away from Marfa, Texas. Called "Prada Marfa," the purpose of the structure was to eventually disintegrate into its surroundings. Shoes and bags were provided by Miuccia Prada from the Summer Season 2005 collection.[89] The installation was looted after being completed, and the restoration needed led to a revise in plans, making the structure a permanent installation.[90]

Philanthropy and sponsoring

[edit]Arts and architecture

[edit]Inaugurated in 2000, Prada's Milan Headquarters are located in a former industrial space between via Bergamo and Via Fogazzaro.[91] An art installation by Carsten Höller that takes the form of a three-story metal slide leads from Miuccia Prada's office to the interior courtyard.[92]

Completed in 2002, Prada's New York City Headquarters open, located in a former Times Square piano factory renovated by the Herzog & de Meuron architecture firm.[93]

2003 – "Garden-Factories" Project – Prada collaborates with architect Guido Canali to rejuvenate the landscape surrounding their manufacturers.[57]

In 2004, "Waist Down – Skirts by Miuccia Prada" bowed at the Tokyo Epicenter. A traveling exhibition featuring 100 skirts designed by Miuccia Prada and conceived by curator Kayoko Ota of AMO in collaboration with Mrs. Prada, the exhibition went on to Shanghai, New York, Los Angeles and Seoul.[94]

Completed in 2009, Prada commissioned an unusual multi-purpose building from Rem Koolhaas's OMA group called the Prada Transformer in Seoul.[95] The building was first used to display the "Waist Down – Skirts by Miuccia Prada" exhibition, and later changed into a movie theater.

In 2012, Mrs. Prada, along with designer Elsa Schiaparelli, was the subject of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition, "Impossible Conversations".[96] The Los Angeles Epicenter was also restored in 2012.[97]

In 2014, an exhibition called "Pradasphere" bowed in London's Harrods and Hong Kong's Central Ferry Pier 4, highlighting the Prada universe.[98]

In 2015, Prada opened a permanent home for Fondazione Prada in Milan. Located in a former distillery redesigned by Rem Koolhaas's OMA group, it hosts a permanent collection of site-specific art as well as galleries of rotating exhibits. Intended to act as a gathering space for the local community,[99] it also features a performance space, movie theater, bookstore, and a cafe – Bar Luce,[100] with an interior designed by director Wes Anderson.[101]

In 2016, after 6 years of restoration Prada opened an events space in a historic residence in the Rong Zhai district of Shanghai, China.[102]

Sports sponsoring

[edit]Patrizio Bertelli's passion for sailing led Prada to form Team Luna Rossa in 1997 in order to participate in the America's Cup.[57] On 28 September 2017 it was announced by the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron[103] that Prada will be the hosting sponsor of Challenger Selection Series at the 2021 America's Cup, superseding the role of Louis Vuitton started in 1983.

The Challenger Selection Series that was the Louis Vuitton Cup, will now be known as the Prada Cup, and the America's Cup Match will be presented by Prada. It will be held in Auckland, New Zealand, January 2021.[104]

Environmental sustainability

[edit]The luxury Group, Prada, allied with UNESCO's Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission in 2019 to introduce an 'educational program', SEA BEYOND, about sea-peservation.[105] The rationale behind such an educational project is to sensibilize the youth and make them aware of 'ocean pollution' and the importance of preserving the sea.[106] At the Sustainable Fashion Awards 2022, the project SEA BEYOND, which simultaneously included 'ocean-literacy' and 'sustainable fashion', received an award.[106] In June 2023, Prada announced its plan to increase its financial support for the Sea Beyond project.[107] Accordingly, for the next two years, the Italian luxury brand will donate 1% of sales revenues from its Re-Nylon collections.[108][109] This will allow the project to broaden its scope beyond ocean education with two ocean-related fields of action; support for scientific research and community projects.[110] Also in December 2023, Prada unveiled its engagement to the UN’s Global Compact (UNGC) initiative which reflected its commitment to work according guiding principles relating to human rights, the environment, labour and anti-corruption.[111]

In January 2024, Prada announced its new partnership with the international non-profit organization Bibliothèques Sans Frontières involves the creation of a resource space dedicated to the seabed.[112]

Prada Female Discrimination Case

[edit]Prada Female Discrimination Case was the first women's rights lawsuit and movement of luxury fashion industry that appeared in the global media in 2010. It was named “David vs. Goliath” by the global NGOs leader. The Prada Female Discrimination Case occurred 4 years after the Me Too movement and was started by activist, Tarana Burke.[113][114]

On December 10, 2009, Bovrisse filed a lawsuit against Prada Japan accusing them of discriminating against women in the workplace.[115][116] Prada Luxembourg (where the trademark is registered) countersued for defamation, stating "voicing women's rights damaged Prada's brand logo."[117][118][119][120]

In May 2011, the Feminists rallied outside the Tsim She Tsui branch of Prada, calling on the Hong Kong exchange to veto the brand's initial public offering (IPO).[121] In May 2012, a Labour Network Monitoring Asian Transnational Corporations issued a letter against LVMH Group on appointing Sebastian Suhl as COO of Givenchy while he was in the case of sexual harassment in Japan and Luxembourg.[122] In October 2012, Tokyo District Court Judge Reiko Morioka ruled in favor of Prada, saying their alleged discrimination was “acceptable for a luxury fashion label.”[123] Bovrisse claimed the court was not fair and accused the judge of screaming at her. Bovrisse took her discrimination claims to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[124] The committee, without mentioning Bovrisse, did issue a report to the Japanese Government urging them to enact regulations that would make sexual harassment in the workplace illegal.[119][120][125][126][127][128][129]

Labor rights

[edit]Prada is the main buyer from the Turkish leather factory DESA, which was found guilty by the Turkish Supreme Court of illegally dismissing workers who joined a union.[130] The Clean Clothes Campaign, a labor rights organization based in Europe, has called on Prada to ensure that freedom of association is respected at the factory.[131] On 30 January 2013 Clean Clothes Campaign reported, "Trade Union Harassment Continues at Prada Supplier".[132]

Research of the social democratic party in the European Parliament, the Sheffield Hallam University and further Groups accused Prada in 2023 of using forced labour camps exploiting muslim Uyghurs in china provided by the Anhui Huamao Group Co., Ltd. for production.[133]

Ostrich leather

[edit]In February 2015, a report in The New York Times by Charles Curkin was published about the use of ostrich leather by luxury fashion brands and the brutal methods by which it is removed from the flightless birds. It was based on a months-long investigation conducted by PETA and namechecked Prada as one of fashion's key brands dealing in products made from ostrich skin.[134]

Blackface imagery

[edit]On 14 December 2018 Prada was forced to pull a new range of accessories and displays from its stores following complaints that they featured "blackface imagery." Prada scrapped the products after outrage spread online when a New Yorker spotted the character at the Prada's Soho store and blasted the brand for using "Sambo like imagery" in a viral Facebook post.[135]

Prada stated in a tweet in response, "Prada Group never had the intention of offending anyone and we abhor all forms of racism and racist imagery. In this interest we will withdraw the characters in question from display and circulation."[135]

In response to the incident, Prada assembled a diversity and inclusion advisory council co-chaired by Ava DuVernay and Theaster Gates.[136]

Investigation on tax evasion

[edit]As of 2014[update], Prada was being investigated by Italian prosecutors for possible tax evasion after the luxury-goods company disclosed undeclared taxable income. Prada SpA Chairman Miuccia Prada, Chief Executive Officer Patrizio Bertelli and accountant Marco Salomoni have been named in the probe, which is for possible undeclared or false tax claims.[137] The chairwoman of Prada faced an investigation after it was alleged the company avoided nearly £400 million in tax by transferring services abroad.[138] Italy's Corriere della Sera newspaper said on Friday Prada and Bertelli had paid 420 million euros ($571 million) to Italy's tax agency to settle their tax affairs. Despite the settlement, an investigation continued.[139] As of 2016, prosecutors requested the case be dropped as the debt had been settled.[140]

See also

[edit]- Lavender Prada dress of Uma Thurman, a 1995 dress worn to the Academy Awards

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Prada Group Annual Report 2023" (PDF). pradagroup.com. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Analysis | Prada's New CEO Takes the Reins at a Delicate Time". Washington Post. 8 December 2022. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Zargani, Luisa (14 May 2015). "Prada and Luxottica Renew Eyewear License". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Arnett, George (12 December 2019). "Prestige beauty battle heats up with L'Oréal-Prada deal". Vogue Business. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ "Prada Reports Record-High Annual Revenue". Hypebeast. 9 March 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Beauloye, Florine Eppe (24 August 2023). "Top 15 Most Popular Luxury Brands Online (2023 Ranking)". Luxe Digital. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ admin (23 May 2023). "Luxury Brand Ranking 2023 – Unveiling the Top Luxury Icons". Mediaboom. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Grosvenor, Carrie. "The History of Prada". Life in Italy. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ "Prada Group". Prada Group. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ "How Mario Prada Built an Empire in the Fashion Industry". DSF Antique Jewelry. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Prada. Internet Archive. Milan : Progetto Prada Arte. 2009. ISBN 978-88-87029-44-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Miuccia Prada tra i candidati a ricevere l'Ambrogino d'oro 2023" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Miuccia Prada". Life in Italy. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Prada: origini e storia di una maison emblematica" (in Italian). Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ a b "SS 1998 Menswear". Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Lugli, Emanuele (2019). "Prada, Ugliness, and Birds". Animalia Fashion, ed. By Patricia Lurati: 137–141.

- ^ Forden, Sara G. (2012). The House of Gucci : a Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062222671. OCLC 841311813.

- ^ Givhan, Robin (4 December 2000). "Givenchy's Loss, Gucci's Gain". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "When Prada acquired Helmut Lang". 7 September 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Cowell, Alan. "Prada in $170 Million Deal For Church, the Shoemaker". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Menkes, Suzy (13 October 1999). "Prada and LVMH Join Forces to Buy Italian Fashion House Fendi". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Prada Sells Stake in Fendi for $265 Million". The New York Times. 26 November 2001. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Menkes, Suzy (September 23, 2008). "Prada takes a tumble". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Photo (High Quality)". ekstrabladet.dk. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Model Katie Fogarty helped by spectators Archived February 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Model Katie Fogarty removing her high heels..." cmestatic.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "... then walking with the shoes in her hands". Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- ^ PiyoPiyoNaku (September 30, 2008). "Prada S/S 09 finale mishap". Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Two Models Fall, Many Stumble at Prada". nymag.com. September 24, 2008. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Close-up photo of the little socks and shoes". novinky.cz. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Model Yulia Kharlapanova losing her balance when her left sock slips out of the shoe". tumblr.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Prada high heel disaster: enough of this stiletto tyranny - Telegraph". fashion.telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "At Prada, Milano". thesartorialist.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Imogen Fox (May 6, 2011). "Prada's attempts to storm Chinese market hit by feminist protesters". the Guardian. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Hong Kong Feminists Bristle at Prada IPO". WWD. May 3, 2011. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Photo from Getty Images - Hong Kong Legislative Council member Lee News, photos, topics, and quotes". Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ "Prada strengthens on Hong Kong debut". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prada Hong Kong debut lackluster". June 25, 2011. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "The China Post". The China Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Prada HK IPO fails to meet expectations". finance. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Interactive Stock Chart for Prada SpA (1913)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014.

- ^ Gonzalez-Rodriguez, Angela (April 1, 2015). "Prada earnings take a 30 percent cut in 2014". FashionUnited. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ "Prada is now available to buy online. Here's our fantasy shopping edit". Archived from the original on July 20, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Sanderson, Rachel (12 March 2018). "Prada shares soar on sale growth outlook". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Jacopo Prisco, "Prada to go fur-free in 2020," CNN, 22 May 2019.

- ^ Friedman, Vanessa (23 February 2020). "Raf Simons Becomes Co-Creative Director at Prada". The New York Times.

- ^ Sarah Maisey, "Valentino and Prada to halt use of alpaca wool and kangaroo leather," The National 17 August 2020.

- ^ PRADA resort 21 03 November, 2020. Vanity Teen.

- ^ Zargani, Luisa (26 January 2023). "Andrea Guerra Kicks Off New Prada Group Phase". WWD. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ "Prada hires former Luxottica chief Andrea Guerra as new CEO". Reuters. 6 December 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Prada Is Coming to New York For Its Cruise 2019 Show". Fashionista. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Prada's Premonition: Taking Over Times Square". brandchannel. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ gq.com (15 January 2012). "Prada's Model Actors". GQ. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "'The Walking Dead' heartthrob Norman Reedus used to be a Prada model in the '90s". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Palimpsest: The Absence and Presence of Miuccia Prada". September 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

(Miuccia Prada's) long-term collaborator Frederic Sanchez's auditory accompaniment was composed of ghostly snatches and layers of jazz, which he defined as 'A disorientation of time, where your head is full of memories – fragments of a life.'

- ^ "Galleria 1913". www.prada.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d "History". PradaGroup. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "New York". www.prada.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "178 PRADA AOYAMA – HERZOG & DE MEURON". www.herzogdemeuron.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Tokyo". www.prada.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Los Angeles". www.prada.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Cat Tsang (October 2009). "Prada: the personal touch". Glass Magazine. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ "Prada returns to Dubai by opening its largest boutique ever". Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Appleseed: Ex Machina x Prada". HYPEBEAST. 26 June 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Dazed (23 February 2010). "Prada at the Opera". Dazed. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (21 January 2013). "Prada reveals 'Gatsby' collection". Variety. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Puig invests 20 million in Prada". Economía digital. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Weil, Jennifer (12 December 2019). "Prada, L'Oréal Sign Beauty License". WWD. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Prada presenta infusion de fleur d'oranger, il primo profumo della infusion ephemeral collection". pambianconews.com (in Italian). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Smells like Prada - La storia e il profumo di un brand". nssmag.com (in Italian). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Prada Introduces Amber Pour Homme". wwd.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Nove filmati per il lancio del nuovo Infusion d'Homme di Prada". pambianconews.com (in Italian). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Prada Amber Pour Homme Intense Prada cologne – a fragrance for men 2011". www.fragrantica.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prada lancia la nuova campagna per l'eau de parfum Candy". milanofinanza.it (in Italian). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Prada Launch 10 New Fragrances: Prada Olfactories | LOVE". LOVE. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Prada Out to Break Fragrance Stereotypes With Les Infusions de Prada". wwd.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Prada Launches New Fragrances". Harper's BAZAAR. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Mia Goth is the Face of Prada Intense". CR Fashion Book. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Levinson, Lauren. "Prada La Femme Prada L'Eau Eau de Toilette Spray". POPSUGAR Beauty. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Jake Gyllenhaal On Starring In Prada's New Fragrance Campaign And His Favorite Smells". forbes.com. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Prada celebra la fragranza Paradoxe con un party a Londra". milanofinanza.it (in Italian). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Weil, Jennifer (28 July 2023). "EXCLUSIVE: Prada Beauty to Launch Makeup and Skin Care". WWD. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Trakoshis, Angela (3 August 2023). "Prada Beauty Is the Luxury Beauty Brand We Needed". Allure. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Orologi Prada, The Link con tecnologia Bluetooth". January 3, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Axiom Space, Prada Unveil Spacesuit Design for Moon Return".

- ^ Quotes from "10 Things I Hate About You", retrieved 24 May 2018

- ^ ""The Devil Wears Prada" Costume Designer Patricia Field Tells All". Racked. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Amiel, Barbara (1 July 2006). "The 'Devil' I know". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Eric (29 September 2005). "Little Prada in the Desert". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Novovitch, Barbara (8 October 2005). "Vandal Hated the Art, but, Oh, Those Shoes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Milano via Bergamo 21 | Prada Group". PradaGroup. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "This Epic Slide Makes Us Wish We Worked For Prada (PHOTO)". The Huffington Post. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Headquarters USA | Prada Group". PradaGroup. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Prada Waist Down". OMA. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Prada Transformer". prada-transformer.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Schiaparelli and Prada: Impossible Conversations". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Epicenter Los Angeles | PRADA".

- ^ "Pradasphere". www.prada.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "History – Fondazione Prada". www.fondazioneprada.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Bar Luce – Fondazione Prada". www.fondazioneprada.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Wes Anderson Designed a Bar in Milan and It's Pretty Much Perfect". Vogue. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Rong Zhai". www.prada.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ TOM, EHMAN (September 28, 2017). "AC36: Protocol (Notice of Race) has just been announced in Auckland at RNZYS; it's Back to the Future". sailingillustrated.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ "Who will be the America's Cup 2021 challenger? Key points to know about the Prada Cup 2021". Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "UNESCO-IOC AND PRADA GROUP TOGETHER FOR SEA BEYOND". UNESCO-IOC. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Project by UNESCO and Prada Group receives the Oceans Award at CNMI Sustainable Fashion Awards 2022". Ocean Decade. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ "Prada renforce son engagement pour la protection des océans". Fashion Network. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Prada va reverser 1% de sa ligne Re-Nylon à la protection des océans". Journal du Luxe. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Prada to Donate 1 Percent of Re-Nylon Revenues to Helping Oceans". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "UNESCO and Prada Group partner for Ocean Literacy". UNESCO. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Prada signs UN global compact". Ecotextile. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ "Un nouveau projet RSE pour Prada Sea Beyond". Journal du Luxe. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Eidelson, Josh (14 November 2013). "Prada, suicide and sexual harassment: A whistle-blower speaks out". Salon. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "Prada Employee Fought Back, And So Did Prada". HuffPost. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Lauren Leibowitz (April 24, 2013). "Prada Employee's Lawsuit Now Involves 'Discrimination,' Aid From UN". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Matsutani, Minoru (12 March 2010). "Prada accused of maltreatment". The Japan Times. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Minoru Matsutani (August 25, 2010). "Prada countersues plaintiff claiming harassment". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Prada countersues plaintiff claiming harassment". Japan Times. August 25, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Japan Prada Case Probes High-Fashion Harassment". Women's eNews. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Prada Wears Devil in Eyes of This 'Ugly' Woman: William Pesek". Bloomberg.com. 9 September 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Fox, Imogen (6 May 2011). "Prada's attempts to storm Chinese market hit by feminist protesters". The Guardian.

- ^ "AGAINST LVMH GROUP ON APPOINTING SEBASTIAN SUHL AS COO OF GIVENCHY WHILE THE CANDIDATE IS IN THE CASE OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND DISCRIMINATION CASE IN PRADA JAPAN AND PRADA LUXEMBURG". 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Fired Prada staffer's battle turns ugly". nydailynews.com. April 24, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Ella Alexander (May 28, 2013). "Prada Vs The UN". Vogue News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Concluding observations on the third periodic report of Japan, adopted by the Committee at its fiftieth session (29 April-17 May 2013)". United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ^ Cowles, Charlotte (23 May 2013). "U.N. Pressures Prada to Stop Sexual Discrimination in Japan". The Cut. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Bohrer, Fujita, Stephen, Miki (1 June 2013). ""THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA WITH DISCRIMINATING FASHION – AN OVERVIEW OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT CLAIMS IN JAPAN"" (PDF). Nishimura & Asahi. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sahny, Pooja (6 June 2013). "Prada Japan being sued by ex-employee". The Upcoming. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Bryant, Kenzie (25 June 2013). "Prada Fails to Shut Down Bad Press Over Sexual Harassment Suit". Racked. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Displaying items by tag: Prada - Labour Behind the Label". Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Luxury Brands Drag Their Feet, DESA Workers Fight for Their Lives". Archived from the original on 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Trade Union Harassment Continues at Prada Supplier". Clean Clothes Campaign. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ "Tailoring Responsibility" (PDF). Tracing Apparel Supply Chains from the Uyghur Region to Europe. Uyghur Rights Monitor, the Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University. p. 17.

- ^ Curkin, Charles (25 February 2016). "PETA Revives Luxury Fight". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Lang, Cady. "Prada Pulls Keychain After Blackface Comparison Backlash". Time. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Alex, Ella; er (14 February 2019). "Prada launches a diversity council led by Ava DuVernay". Harper's BAZAAR. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Prada Said to Be Under Investigation for Tax Evasion". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014.

- ^ "Prada, indagine fiscale su Miuccia e Patrizio Bertelli". la Repubblica (in Italian). 29 September 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Prada owners under investigation for tax avoidance - sources". Reuters. January 10, 2014. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Prosecutors seek to close Prada CEO tax case: sources". U.S. Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

External links

[edit] Media related to Prada at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prada at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Prada – brand and company profile at Fashion Model Directory

- Prada Logo SVG - Unofficial

- Prada

- Italian companies established in 1913

- Bags (fashion)

- Clothing brands of Italy

- Clothing companies established in 1913

- Companies listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange

- High fashion brands

- Italian Royal Warrant holders

- Luxury brands

- Manufacturing companies based in Milan

- Eyewear brands of Italy

- Shoe companies of Italy

- Watch manufacturing companies of Italy

- Design companies established in 1913