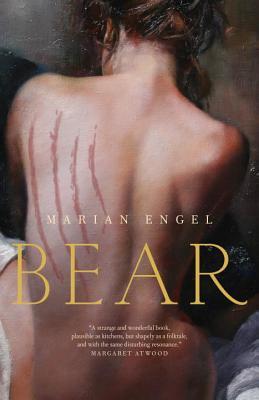

Carolyn's Reviews > Bear

Bear

by

by

In Engel’s novel, Lou and Bear’s relationship is not consensual; many of their encounters are sexually abusive, verging on rape. As Margret Grebowicz argues in “When Species Meat: Confronting Bestiality Pornography,” “[h]ow might we begin to distinguish between the sexual agency we anthropomorphically project onto animals (in the production of porn, for instance) and their real sexual agency, the very thing which render them rapeable (at least in human legal terms) in the first place?” Because animals cannot verbally give informed consent, they are legally in line with humans who cannot — for instance, the severely mentally handicapped and underaged people — in this way, all sexual encounters with animals are rape. Bear cannot give informed consent because of the language barrier between his suitors and himself, which makes him rapeable; in Bear’s case, raped. Bear’s encounters with Lou are an example of this sexual abuse of power taken by a caregiver, made possible by Bear’s conditioned submissive nature.

Ethically, animals are not responsible — nor should they be — to uphold human laws, but humans are. Restricting animals such as Bear by human-invented constructs of sexual agency and the concept of informed consent is to measure them by standards outside of their species. This is not the case when a human commits a crime against an animal. Sex without informed consent with an animal — human or otherwise — is rape. As Jeremy Bentham argues, the line between “us” and “them” is not our intelligence or ability to communicate and understand one another, but our ability to suffer (Bentham). Therefore, if an animal suffers under abuse as a human does, they are no different in terms of rape victimhood.

Lou does not see herself as a bear, or Bear as a human, nor does she have any delusion that Bear could give informed consent. “She had no idea what animals were about. They were creatures. She supposed that they led flickering, inarticulate psychic lives as well” (Engel 46); Lou thinks of Bear as a thoughtless brute, yet still believes she is right in trying to have sex with him, knowing she cannot get informed consent. Lou’s forcing herself on Bear is especially abusive in the case of her attempted rape because she not only abuses his physically — sexually — she does not respect him on an emotional or mental level either.

Stockholm syndrome is a “psychological condition in which hostages or victims of kidnappings sometimes develop positive feelings towards their captors, on whom they depend for their survival” (Colman). Lou seems disinterested in understanding the Bear and his mind, more interested in his body.

In Greg Garrard’s “Being Zoo”, he cites an interview with a zoophile who expresses his distrust of condemning bestiality; “[i]t is unthinkable that any sexual act with an animal is punished without proof that the animal has come to any harm” (2). In Bear and Lou’s relationship, it is clear that manipulation and conditioning is at play.

Lou and Bear’s relationship is tenuous and unstable. Lou is only at the Cary house for a summer. Lou takes advantage of a bear that has been a captive of humans for many years, possibly sexually abused by Lucy, the Indigenous woman, and the Colonel. In this way, Bear could have developed Stockholm Syndrome himself, forced to be docile and submissive around his keepers, even when he could physically overwhelm them. Bear is described as “a middle-aged woman defeated to the point of being daft. . .I can manage him, she decided” (Engel 23). Here, Lou positions herself as the dominant in their relationship, both believing the bear to be “defeated” and “daft,” that is passive and stupid, and deciding that she can manage, control, abuse him, take advantage of her fiduciary position.

In the instances where the bear ‘initiates’ sexual contact, it is made clear by Engel that he is not visibly aroused, that is, not erect. Therefore, it is feasible to argue that he does not treat licking Lou as a sexual act, more as an act that simply makes her happy, and through her contentment, more likely to give him treats, take him to the water, and play with him. This is another sign of conditioned response; he has been trained to please his captors. Lou says, “I don’t care if I can’t turn you on, I just love you” (Engel 90). In that way, she does not care if he is attracted to her; that is not important. Lou has never needed consent to feel she has right to abuse Bear.

The only instance in which Bear becomes erect is at the climax of the novel; here, Lou notices his arousal and tries to have sex with him but is injured instead (Engel 106-107). There is no preamble, no attempt on his part to be submissive and please her;

[s]he looked at him. He did not move. She. . .went down on all fours in front of him, in the animal posture. He reached out one great paw and ripped the skin on her back. . .[she] [t]urned to face him. He had lost his erection and was sitting in the same posture. She could see nothing, nothing in his face to tell her what to do. (Engel 107)

While this wound inflicted on her back could be an accident or a part of regular bear mating, it is understood by the reader to be a violent act that drives Lou away, perhaps Bear’s intention. The one instance when penetrative rape is truly threatening him, he acts violently, never having shown a violent or aggressive side before in the novel. His sexual agency was encroached upon, and he responded in defense. As well, his erection is lost as soon as she assumes the “animal posture,” a sign that he does not wish to have sex with her. This moment is another attempted rape of Bear, and while he did not attack her the first time, he is ready to defend himself and his sexual agency in this instance. Garrard argues that Bear’s reasoning behind his act of harming Lou “remains unknowable, it can hardly be “‘neutral,’” and goes on to argue that it is the moment when Bear is no longer an object to Lou, the moment she is seeing his selfhood for the first time (Garrard 26). The moment when the bear’s agency and personhood is finally clear to Lou is his attack on her, ripping at her skin. Paul Barrett’s “Animal Tracks” cites Elspeth Cameron who argues that the protagonist’s “relationship with the bear is emblematic of her tentative exploration of, gradual immersion in, and full acceptance of the primitive forces in the world and herself” (Barrett 125). This is yet another critic who is content to see an anthropomorphized, allegorized bear rather than the person himself. If we interpret Bear as a symbol of Lou’s sexuality, or “the Wild, the Canadian North, the Romantic spirit, or masculinity” (Garrard 19), then his sexual agency is unimportant as he is not really a bear. Of course, if he is a bear, as the facts of the narrative point out clearly to us through its clear and frequent physical descriptions of Bear, he is grossly abused by the protagonist, his sexual agency disregarded as she attempts twice to rape him.

With Lou and Bear, the relationship is obviously manipulative and abusive. In Bear, Lou takes advantage of Bear’s dependency on her, his conditioned submissive nature to please her, regardless of his own awareness of his place in her sexuality. She leaves with no care for the bear’s future, showing her true disinterest in his mind and identity, only having used him as a way to explore her own sexual identity.

Ethically, animals are not responsible — nor should they be — to uphold human laws, but humans are. Restricting animals such as Bear by human-invented constructs of sexual agency and the concept of informed consent is to measure them by standards outside of their species. This is not the case when a human commits a crime against an animal. Sex without informed consent with an animal — human or otherwise — is rape. As Jeremy Bentham argues, the line between “us” and “them” is not our intelligence or ability to communicate and understand one another, but our ability to suffer (Bentham). Therefore, if an animal suffers under abuse as a human does, they are no different in terms of rape victimhood.

Lou does not see herself as a bear, or Bear as a human, nor does she have any delusion that Bear could give informed consent. “She had no idea what animals were about. They were creatures. She supposed that they led flickering, inarticulate psychic lives as well” (Engel 46); Lou thinks of Bear as a thoughtless brute, yet still believes she is right in trying to have sex with him, knowing she cannot get informed consent. Lou’s forcing herself on Bear is especially abusive in the case of her attempted rape because she not only abuses his physically — sexually — she does not respect him on an emotional or mental level either.

Stockholm syndrome is a “psychological condition in which hostages or victims of kidnappings sometimes develop positive feelings towards their captors, on whom they depend for their survival” (Colman). Lou seems disinterested in understanding the Bear and his mind, more interested in his body.

In Greg Garrard’s “Being Zoo”, he cites an interview with a zoophile who expresses his distrust of condemning bestiality; “[i]t is unthinkable that any sexual act with an animal is punished without proof that the animal has come to any harm” (2). In Bear and Lou’s relationship, it is clear that manipulation and conditioning is at play.

Lou and Bear’s relationship is tenuous and unstable. Lou is only at the Cary house for a summer. Lou takes advantage of a bear that has been a captive of humans for many years, possibly sexually abused by Lucy, the Indigenous woman, and the Colonel. In this way, Bear could have developed Stockholm Syndrome himself, forced to be docile and submissive around his keepers, even when he could physically overwhelm them. Bear is described as “a middle-aged woman defeated to the point of being daft. . .I can manage him, she decided” (Engel 23). Here, Lou positions herself as the dominant in their relationship, both believing the bear to be “defeated” and “daft,” that is passive and stupid, and deciding that she can manage, control, abuse him, take advantage of her fiduciary position.

In the instances where the bear ‘initiates’ sexual contact, it is made clear by Engel that he is not visibly aroused, that is, not erect. Therefore, it is feasible to argue that he does not treat licking Lou as a sexual act, more as an act that simply makes her happy, and through her contentment, more likely to give him treats, take him to the water, and play with him. This is another sign of conditioned response; he has been trained to please his captors. Lou says, “I don’t care if I can’t turn you on, I just love you” (Engel 90). In that way, she does not care if he is attracted to her; that is not important. Lou has never needed consent to feel she has right to abuse Bear.

The only instance in which Bear becomes erect is at the climax of the novel; here, Lou notices his arousal and tries to have sex with him but is injured instead (Engel 106-107). There is no preamble, no attempt on his part to be submissive and please her;

[s]he looked at him. He did not move. She. . .went down on all fours in front of him, in the animal posture. He reached out one great paw and ripped the skin on her back. . .[she] [t]urned to face him. He had lost his erection and was sitting in the same posture. She could see nothing, nothing in his face to tell her what to do. (Engel 107)

While this wound inflicted on her back could be an accident or a part of regular bear mating, it is understood by the reader to be a violent act that drives Lou away, perhaps Bear’s intention. The one instance when penetrative rape is truly threatening him, he acts violently, never having shown a violent or aggressive side before in the novel. His sexual agency was encroached upon, and he responded in defense. As well, his erection is lost as soon as she assumes the “animal posture,” a sign that he does not wish to have sex with her. This moment is another attempted rape of Bear, and while he did not attack her the first time, he is ready to defend himself and his sexual agency in this instance. Garrard argues that Bear’s reasoning behind his act of harming Lou “remains unknowable, it can hardly be “‘neutral,’” and goes on to argue that it is the moment when Bear is no longer an object to Lou, the moment she is seeing his selfhood for the first time (Garrard 26). The moment when the bear’s agency and personhood is finally clear to Lou is his attack on her, ripping at her skin. Paul Barrett’s “Animal Tracks” cites Elspeth Cameron who argues that the protagonist’s “relationship with the bear is emblematic of her tentative exploration of, gradual immersion in, and full acceptance of the primitive forces in the world and herself” (Barrett 125). This is yet another critic who is content to see an anthropomorphized, allegorized bear rather than the person himself. If we interpret Bear as a symbol of Lou’s sexuality, or “the Wild, the Canadian North, the Romantic spirit, or masculinity” (Garrard 19), then his sexual agency is unimportant as he is not really a bear. Of course, if he is a bear, as the facts of the narrative point out clearly to us through its clear and frequent physical descriptions of Bear, he is grossly abused by the protagonist, his sexual agency disregarded as she attempts twice to rape him.

With Lou and Bear, the relationship is obviously manipulative and abusive. In Bear, Lou takes advantage of Bear’s dependency on her, his conditioned submissive nature to please her, regardless of his own awareness of his place in her sexuality. She leaves with no care for the bear’s future, showing her true disinterest in his mind and identity, only having used him as a way to explore her own sexual identity.

Sign into Goodreads to see if any of your friends have read

Bear.

Sign In »

Reading Progress

February 26, 2016

–

Started Reading

February 26, 2016

– Shelved

March 1, 2016

– Shelved as:

2016

March 1, 2016

– Shelved as:

my-real-life-bookshelf

March 1, 2016

–

Finished Reading

Comments Showing 1-3 of 3 (3 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Peter

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Sep 06, 2016 07:27AM

Funny! Or at least I hope this comment is meant to be satire.

Funny! Or at least I hope this comment is meant to be satire.

reply

|

flag