What do you think?

Rate this book

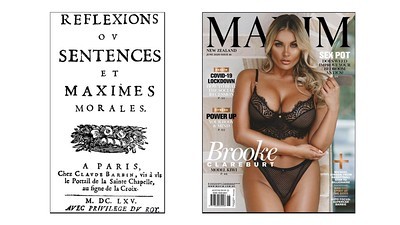

126 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1665

the same may be said of his Maxims. Few books as widely read have provoked as much resistance. Most of us can no more look at it without wavering than we could the sun. We cannot bear the thought that it might be true; the consequences would be too painful. So, to shut our eyes to it, to avoid facing it, we rely on every psychological defence we can muster. The book is a work of cynicism, pessimism, scepticism, Jansenism, or some other limited and limiting -ism; we ourselves are much wiser, and take a broader, more balanced view of humanity. Or it is inconsistent, and contains its own refutation. Or it is true only of La Rochefoucauld himself (how corrupt he must be, to be capable of thinking us corrupt!). Or it may be true of many people, but it is not true of us. Or if it is, it is true of us only in our worst moments, or only in some details. Or if we do happen to entertain the thought that it might be wholly true, we entertain that thought only while actually reading it; a few minutes later we put the book aside and turn our minds to other, more comfortable things; we live, in practice, as if we had never read it.

There is more pride than kindness in our reprimands to people who are at fault; and we reprove them not so much to correct them as to convince them that we ourselves are free from such wrongdoing.

We would have few pleasures if we never flattered ourselves.

While laziness and timidity keep us to the path of duty, our virtue often gets all the honour.

The sure way to be deceived is to think yourself more astute than other people.

‘The reader’s best policy is to start with the premiss that none of these maxims is directed specifically at him, and that he is the sole exception to them, even though they seem to be generally applicable. After that, I guarantee that he will be the first to subcribe to them.’

Hypocrisy is a form of homage that vice pays to virtue.

We do not like to praise, and we never praise without a motive.

One of the reasons that we find so few persons rational and agreeable in conversation is there is hardly a person who does not think more of what he wants to say than of his answer to what is said. The most clever and polite content themselves with only seeming attentive while we perceive in their mind and eyes that at the very time they are wandering from what is said and desire to return to what they want to say.

"Nathan "N.R." wrote: "There is nothing worse in the world than someone who has fallen in love."

[Moira]: Nathan, you get the La Rochefoucauld (sp) award for the day."

Great minds have the ability to say much in few words.

In short, the reader’s best policy is to start with the premiss that none of these maxims is directed specifically at him, and the he is the sole exception to them, even though they seem to be generally applicable. After that, I guarantee that he will be the first to subscribe to them, and that he will think them only too favourable to the human heart. That is what I have to say about the work in general.

Deceptively brief and insidiously easy to read . . .