What do you think?

Rate this book

584 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1819

Let us have wine and woman, mirth and laughter,

Sermons and soda water the day after.

He might be taught, by love and her together—

I really don't know what, nor Julia either.

What men call gallantry, and gods adultery

Is much more common where the climate's sultry.

But oh, ye lords of ladies intellectual,Or Juan's distress on his exile from Spain:

Inform us truly, have they not hen-peck'd you all?

No doubt he would have been much more patheticAnd as we have seen, Byron can also be quite naughty; here he is describing the interior of a harem, into which Juan has been smuggled disguised as a woman:

But the sea acted as a strong emetic.

'Twas on the whole a nobly furnish'd hall,Every now and then, Byron resists the temptation towards comedy and writes passages of pathos with even a touch of the sublime:

With all things ladies want, save one or two.

And even those were nearer than they knew.

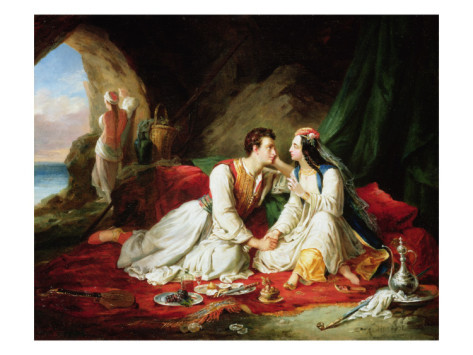

Thus to their hopeless eyes the night was shown,Some of the descriptions of the feasting of Juan and Haidée on her father's island have echoes of Homer or Virgil, and his famous elegy on departed grandeur, "The Isles of Greece," also comes from this section. I could personally have done with more seriousness and less comedy, and these moments were welcome when they came.

And grimly darkled o'er the faces pale,

And the dim desolate deep: twelve days had Fear

Been their familiar, and now Death was here.

There poets find materials for their books,Pointing out that "All tragedies are finish'd by a death; all comedies are ended by a marriage," he asks:

And every now and then we read them through,

So that their plan and prosody are eligible,

Unless, like Wordsworth, they prove unintelligible.

Think you, if Laura had been Petrarch's wife,For the most part, Byron's philosophy is the comfortable one of taking life as it comes:

He would have written sonnets all his life?

Well—well, the world must turn upon its axis,But towards the end of the epic, he reaches towards a deeper explanation of the Romantic search for wider and wilder experiences:

And all mankind turn with it, heads or tails,

And live and die, make love and pay our taxes,

And as the veering wind shifts, shift our sails.

The new world would be nothing to the oldThe soul's antipodes: those indeed are destinations worth punching on one's ticket!

If some Columbus of the moral seas

Would show mankind their souls' antipodes.