What do you think?

Rate this book

300 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2014

The archaeology of grief is not ordered. It is more like earth under a spade, turning up things you had forgotten. Surprising things come to light: not simply memories, but states of mind, emotions, older ways of seeing the world.Helen MacDonald had suffered a great loss. In Anna Karenina, Tolstoy wrote, Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Perhaps the same might be applied to grieving. I know for myself, during an acute period of grieving I was practically unable to speak for well over a month, probably not a typical experience. MacDonald’s reaction was just a wee bit more unusual than mine. She decided to train a goshawk.

I was in ruins. Some deep part of me was trying to rebuild itself, and its model was right there on my fist. The hawk was everything I wanted to be: solitary, self-possessed, free from grief, and numb to the hurts of human life.Hope may be a thing with feathers, but in MacDonald’s case, it was also a thing with a rapier beak, death-dealing claws and a penchant for killing. MacDonald named her Mabel. She takes us along on her year-long struggle to master both her hawk and her grief.

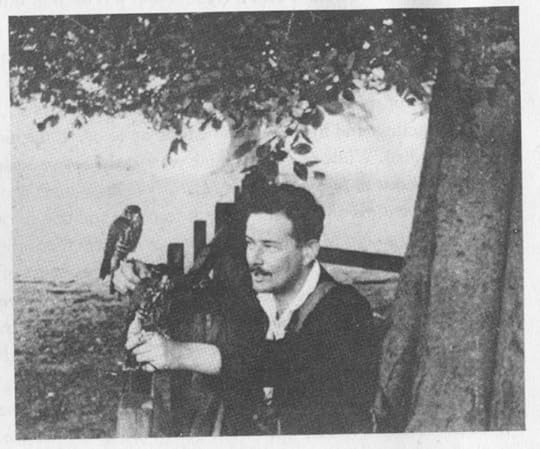

When White writes about his love for the countryside, at heart he is writing about a hope that he might be able to love himself. But the countryside wasn’t just something that was safe for White to love it was a love that was safe to write about. It took me a long time to realize how many of our classical books on animals were by gay writers who wrote of their relationships with animals in lieu of human loves of which they could not speak.Both White and MacDonald used hawking as a way to step away from the world. She also sees an expression of White’s violent inclinations, and recognizes a bloodlust in herself as she assists Mabel in the slaughter of local fauna. In referring to a scene in which White tells of a fox being ripped to bits

In this bloody scene, one man escaped White’s revulsion: the huntsman, a red-faced, grave and gentlemanly figure who stood by the hounds and blew the mort on his hunting horn, the formal act of parting to commemorate the death of the fox. By some strange alchemy—his closeness to the pack, his expert command of them—the huntsman was not horrible. For White it was a moral magic trick, a way out of his conundrum. By skillfully training a hunting animal, by closely associating with it, by identifying with it, you might be allowed to experience all your vital, sincere desires, even your most bloodthirsty ones, in total innocence. You could be true to yourself.This was something that appealed to White, a publicly sanctioned milieu in which he could express his bloody desires. MacDonald recognizes the feeling of bloodlust in herself, as well.

I saw those nineteenth century falconers were projecting onto their hawks all the male qualities they thought threatened by modern life; wildness, power, virility, independence, and strength. By identifying with their hawks as they trained them, they could introject, or repossess, those qualities. At the same time they could exercise their power by ‘civilising’ a wild and primitive creature. Masculinity and conquest; two imperial myths for the price of one.The book is filled not only with her emotional struggle to recover, but with some breath-taking nature writing.

The bare field we’d flown the hawk upon is covered in gossamer, millions of shining threads combed downwind across every inch of soil. Lit by the sinking sun the quivering silk runs like light on water all the way to my feet. It is a thing of unearthly beauty, the work of a million tiny spiders searching for new homes. Each had spun a charged silken thread out into the air to pull it from its hatch-place, ascending like intrepid hot-air balloonists to drift and disperse and fall.Does being in nature offer a salve to human suffering? Or does it reveal more of who we really are? MacDonald obviously survived her trial by feather with her personality, her core, intact. It will not feel entirely clear as you read this that she will. MacDonald is gloriously adept at bringing you into her experience, leading you to wonder the things she wonders, to feel the pain of her struggle. H is for Hawk is a magnificent achievement, taking us along with the author on her dark road, but offering glimpses of glory, of growth and understanding, while teaching us a bit about something most of us have never encountered, and giving us an expanded appreciation for one of the most beloved authors of the 20th Century. If you have not yet had the pleasure of reading H is for Hawk (I know there are some of you out there), I cannot urge you more vociferously to snatch off your hoods, fly to your bookstore and pounce on a copy before they are all gone. You will find in this book a very satisfying feast.

”Everything about the hawk is tuned and turned to hunt and kill. Yesterday I discovered that when I suck air through my teeth and make a squeaking noise like an injured rabbit, all the tendons in her toes instantaneously contract, driving her talons into the glove with terrible, crushing force. This killing grip is an old, deep pattern in her brain, an innate response that hasn't yet found the stimulus meant to release it. Because other sounds provoke it: door hinges, squealing brakes, bicycles with unoiled wheels -- and on the second afternoon, Joan Sutherland singing an aria on the radio. Ow. I laughed out loud at that. Stimulus: opera. Response: kill.

”Her eyes can follow the wingbeats of a bee as easily as ours follow the wingbeats of a bird. What is she seeing: I wonder, and my brain does backflips trying to imagine it, because I can't. I have three different receptor-sensitivities in my eyes: red green and blue. Hawks, like other birds, have four. This hawk can see colours I cannot, right into the ultraviolet spectrum. She can see polarised light, too, watch thermals of warm air rise, roil, and spill into clouds, and trace, too, the magnetic lines of force that stretch across the earth. The light falling into her deep black pupils is registered with such frightening precision that she can see with fierce clarity of things I can't possibly resolve from the generalised blur.”

Here’s a word. Bereavement. Or Bereaved. Bereft. It’s from the Old English bereafian, meaning ‘to deprive of, take away, seize, rob’.

Here’s another word: raptor, meaning ‘bird of prey’. From the Latin raptor, meaning ‘robber,’ from rapere meaning ‘seize’. Rob. Seize.

As a child I’d cleaved to falconry’s disconcertingly complex vocabulary. In my old books every part of a hawk was named: wings were sails, claws pounces, tail a train. Male hawks are a third smaller than the female so they are called tiercels, from the Latin tertius, for third. Young birds are eyasses, older birds passagers, adult-trapped birds haggards. Half-trained hawks fly on a long line called a creance. Hawks don’t wipe their beaks, they feak. When they defecate they mute. When they shake themselves they rouse. On and on it goes in a dizzying panoply of terms of precision.

In real life, goshawks resemble sparrowhawks the way leopards resemble housecoats. Bigger, yes. But bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier, and much, much harder to see. Birds of deep woodland, not gardens, they're the birdwatchers' dark grail. You might spend a week in a forest full of gosses and never see one, just traces of their presence.

What happens to the mind after bereavement makes no sense until later.

"The archeology of grief is not ordered."

"Here’s a word. Bereavement. Or, Bereaved. Bereft It’s from the Old English bereafian, meaning ‘to deprive of, take away, seize, rob.’ Robbed. Seized. It happens to everyone. But you feel it alone. Shocking loss isn’t to be shared, no matter how hard you try. ‘Imagine,’ I said, back then, to some friends, in an earnest attempt to explain, ‘imagine your whole family is in a room. Yes, all of them, All the people you love. So then what happens is someone comes into the room and punches you all in the stomach. Each one of you. Really hard. So you’re all on the floor. Right? So the thing is, you all share the same kind of pain, exactly the same, but you’re too busy experiencing total agony to feel anything other than completely alone. That’s what it’s like’ I finished my little speech in triumph, convinced that I’d hit upon the perfect way to explain how it felt. I was puzzled by the pitying, horrified faces, because it didn’t strike me at all that an example that put my friends’ families in rooms and had them beaten might carry the tang of total lunacy…Hawks apparently have a shamanic tradition of being able to cross borders that humans cannot and "were seen as messengers between this world and the next."

I’d dreamed of hawks again. I started dreaming of hawks all the time. Here’s another word: raptor, meaning ‘bird of prey’. From the Latin raptor, meaning ‘robber,’ from rapere, meaning ‘seize.’ Rob. Seize."