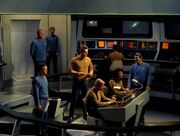

Quintessential Star Trek set: the USS Enterprise bridge

When writer, and later executive producer, Gene Roddenberry submitted his 11 March 1964 "Star Trek is..." pitch to MGM, it was already abundantly clear that a starship called "S.S. Yorktown" would take center stage, meaning that at least some futuristic interior sets were to be constructed for his proposal. As Roddenberry's proposal gained more momentum, for it to become ultimately Star Trek: The Original Series, now featuring the USS Enterprise, requirements for these interiors became more stringent, especially for the bridge, for which Roddenberry stipulated some sort of scientific foundation in ever-increasing graduation once both pilot episodes – "The Cage" and "Where No Man Has Gone Before" – as well as the subsequent original series were in development.

Over the next several years, several Constitution-class interior sets for representing the USS Enterprise were designed and constructed, capturing the imagination of generations of Star Trek fans, who not infrequently indulged in their fascination for these in recreating them on numerous occasions, the original Enterprise bridge being perceived as the quintessential one in particular.

Bridge set[]

When approved, Roddenberry's proposal made it abundantly clear that the bridge of his proposed starship was to become one of if not the most important standing sets for the proposed show, since most of the projected on-board scenes were to take place on the bridge, as it has been for every subsequent Star Trek live-action production ever since. Though established as being instrumental, that was as far as it went; shape, function, size, location, and interior all had to be beefed out and thought about. As early as 24 July 1964, Roddenberry commented in a memo to his art director Pato Guzman, "More and more I see the need for some sort of interesting electronic computing machine designed into the USS Enterprise, perhaps on the bridge itself. It will be an information device out of which April and the crew can quickly and interestingly extract information on the registry of other space vessels, space flight plans for other ships, information on individuals and planets and civilizations, etc. [note: ultimately becoming Spock's Library Computer Access and Retrieval System] This should not only speed up our storytelling but could be visually interesting." (The Making of Star Trek, p. 85) A month later, on 25 August 1964, Roddenberry mused in a memo to Guzman,

"It seems to me likely that design of controls, dials, instruments, etc., aboard our spaceship, particularly the complex "three dimensional" ones which our scientists friends insist would be there, necessitates we locate some hopefully, near genius gadgeteer and electrician and jack-of-all-trades here at Desilu who can augment our speculation and sketching with some idea of what he can accomplish with batteries, lights, wires, plastic, etc. For example, going on an instrument I saw yesterday at North American´s Advanced Space Research Center, is there some way to construct a plain revolving globe on which flicker on and off various small lights, lighted path projections, projected course lines, etc. The point being, although neither you or I may see this as possible or within our budget limits, a highly inventive and mechanically minded person may know of fairly simple ways to accomplish it. In short, I think it's important to locate the best possible man here and, rather than wait for the more formal preproduction meetings, immediately include him in some of our speculating and discussions. If you agree, please call Jim Paisley [note: Desilu's overall production manager]. Have forwarded him a copy of this note." (The Making of Star Trek, pp. 86-87)

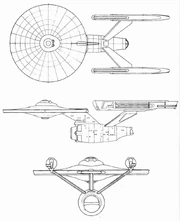

By this time, however, both Matt Jefferies and Guzman were already homing in on the final exterior design of the Enterprise, and their design directions made it already abundantly clear that the bridge was to be circular and situated atop what was to become the saucer section. In the script of "The Cage", the bridge was described thus; "The Enterprise command station is unusually spacious, with controls and instrumentation so highly advanced the net effect is simplicity and attractiveness."

Once Roddenberry and his design advisors had beefed out the format, shape and functions of the bridge, he, once the regular series went into production, proceeded to formalize those in the internal writer's/director's guide, The Star Trek Guide, endowed with the sobriquet "The Writer's Bible" by production staffers (and used for every such document of later Star Trek productions ever since), stated,

INT. BRIDGE-

- a circular, platformed set where Captain Kirk presides over the whole ship's complex. Access is achieved to this set by means of a turbolift elevator which opens directly into the set. Kirk sits in his command chair in the inner, lower elevation facing the large Bridge Viewing Screen. Directly in front of him, also facing the Screen, sit the Navigator and the Helmsman at their individual console. In the outer circular elevation of the set are various positions for Communications Officer and various Technician Crewmen and other ship's officers. Mister Spock, our Science Officer, presides over a console which is known as the "Library-Computer Station". (3rd ed, 17 April 1967, p. 15)

The bridge format as formally laid down has been largely adhered to for every subsequent Star Trek reincarnation, at least as far as Federation/Starfleet starship vessels were concerned.

Original configuration bridge[]

After he was finished with the arduous design of the exterior look for the Enterprise in the early autumn of 1964 for the production of the first pilot "The Cage", then set designer Matt Jefferies, pressed for time due to the drawn-out design process of the ship, immediately set out to work on the design of the bridge. "It was pretty well established with the model that the thing was going to be in a full circle. From there it became a question of how we were going to make it, how it could come apart, where the cameraman could get into it." [1]

Designing the original configuration bridge[]

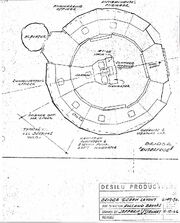

The very first visual representation of the Enterprise bridge by Guzman

Together with his supervisor, Pato Guzman, Jefferies started to hammer out the details. "The original concept of the bridge being circular was from a little water color or pastel sketch that Pato Guzman did. But it only covered about 180 degrees of the circle, so gradually, when we thought about where we were going to locate it on the ship, and about the things we felt could come up as story points, it became full circle. Which had its advantages, because we were getting into molded fiberglass at the time, we could make a mold and instead of just making one section you could make eight of it. So more set was possible for less money; that's what it amounted to." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 20) When Guzman left in October that year because of home sickness, Franz Bachelin took over his position as art director, continuing to put forward designs for what at the time was still called "Control Room". The designs, however, were met with increasing skepticism from Jefferies, as were those of Bachelin's immediate predecessor. "I had to come up with the construction drawings to actually build these sets, and my problem was in trying to figure out just what the hell Bachelin had done such a pretty painting about. I mean in terms of practicality, his paintings just didn't work; the construction crew would have gone out of their minds trying to build what he'd painted. At any rate, as I had said, I was a nuts-and-bolts man, so I took his basic paintings and used them in creating all of the ship's specific design work. I'm talking mainly about the bridge, the layout, the relationships between Enterprise crew members positions, the original instrumentations – all of this stuff required a massive amount of work." (Star Trek Memories, 1994, p. 57)

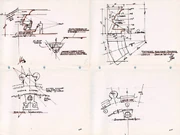

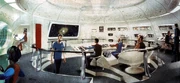

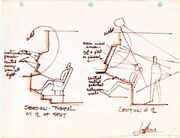

Practical bridge layout concept by Jefferies

Realizing that the smooth circular designs of Guzman and Bachelin, while not beyond the technical capabilities of the contemporary set constructors, was cost-prohibitive, Jefferies proceeded to work on a design that, realistically, was more practical to realize. One of the first things he considered were the conditions any bridge crew had to work under. Taking his cue from his own experiences as a B-17 Flying Fortress pilot, he related, "If you've spent any time around ships or aircraft, then you know that every time a new piece of equipment comes out, you're going to bump your head on it. You've got to duck here and duck there, and if a piece of equipment goes out, then whoever's working with it has got to get out of the way and shut the thing down while they either fix it or replace it. I felt this was kind of stupid, and asked, why don't we change it from the back? Unhook it, pull the thing out, shove a replacement in, and never make the guy have to get up out of his chair." (The Art of Star Trek, p. 7) Later, Jefferies elaborated, "The idea of the whole thing was that if a guy's supposed to be on his toes and alert for hours he's going to have to stay sharp, and if you can make him comfortable it will help. So I felt that everything he had to work with should be at hand without him having to reach for it, and at a comfortable angle. During World War II, I'd been in B-25's and -24s and -17s, and whenever a new piece of equipment came out it would be hung somewhere that you could knock your head on it, and if anything went wrong then the crewman had to get out of the way and they had to pull the thing down and repair or replace it. I thought that was kind of dumb." For working out the various positions on the bridge stations, Jefferies resorted to the simple means of sitting on a chair by a blank wall, holding out his arms at convenient angles and having his younger brother, John Jefferies (who had some time off from his regular employer and decided to give his older brother a hand), mark the appropriate angles on the wall, or as he himself put it, "So for the bridge I pushed a chair for each position up against the wall so it felt like a good angle, and my kid brother, my chief draftsman, drew a line so that when you were sitting, regardless of where you looked, the screens would be at right angles to the eyes and everything was reachable." (The Art of Star Trek, p. 7; Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, pp. 21-22) However, in designing the bridge, there was also a very personal reason involved, as his other brother, Richard, recalled; "Contemplating where to begin, Matt remembered that as a boy, he had often seen his father in the control room of a power plant, where he stood and faced an immense switchboard resplendent with colored lights, switches, and gauges. Having to keep a watchful eye on the performance of all of the plant's systems, he had little opportunity to move away from his station. Matt was determined to design a bridge which would allow the crew to sit comfortably, have the advantage of remote control, and have a clear view of the display monitors. To make the command center a model of high-tech efficiency, he used a hands-on approach to attain the desired results." (Beyond the Clouds, pp. 220-221)

Fine-tuning his bridge design, Jefferies additionally commented, four years later:

"The split-level bridge was not part of the original idea. I did not like it, and in many ways I do not now. There is much to be said for it pictorially, in terms of people movement and picture composition. But it's had a great many difficult ramifications for me. The split-level design limits the type of camera shot you can do, for example. For any close-ups of people on the bridge, you have to jack the camera up off the floor. Another problem that resulted from the split-level design is the high noise level in the bridge. The original bridge was built in 'wild' [separate] sections. These sections have a tendency to squeak a great deal because they weaken and loosen from daily usage, being pulled in and out and moved around. "Franz and I have worked out how many people would be on the bridge and what their functions would be. Then Franz proceeded with the design of the rest of the sets of the pilot and left me alone with the bridge. The first thing I did was to work out the size of the units and the shapes of the consoles and screens at each station. I then made a full-size cut-out of each screen, pinned it up on a wall, and sat back in a chair in front of it in order to check the feel of the thing, and how high the screens were to look at. When that checked out properly, I set to work drawing full-size layouts for every button, panel, screen, console, and the eight instruments on each of the eight sections. The full-size drawings were then sent to the construction department so that they could begin building the actual sets. at the same time, I called in the special effects man and got him started building the electrical boxes and equipment that would be needed to light all of those buttons, screens, and so forth. After choosing the proper colors that I wanted for the various view screens and components around the bridge, the final assembly stage was relatively easy." (The Making of Star Trek, pp. 102, 106)

In later years, Jefferies made some additional remarks on his design; "The elevated platform came about two ways. It had to be elevated to some extent because we had to be able to roll sections in and out, and then we had to get in so we could soundproof the thing, because it became a terrible drum, even with soft-soled shoes." Another aspect he did not quite foresee was the enthusiasm with which episode directors took to the novel circular design. "Of course every director wanted to get in there and shoot a 360. We did our damnedest to talk them out of it because we knew we were going to wind up on the cutting room floor; the whole world would go by too quick to see anything! So that only happened once or twice." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, pp. 20-21)

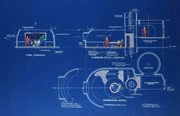

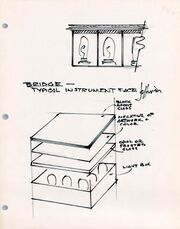

Bridge console display light box design

In regard to the bridge instrumentation, Jefferies elaborated, "I decided that the crewman would work like in the navy, so often would be on for four hours, off eight hours, and it had better be comfortable. The switches would all be so that the crewman doesn't have to reach for anything. Each of the viewing screens would be at right-angles to his eyes, and we drew a full size section of the bridge that way. I wanted an all-black instrument panel that would light up from behind which is pretty much what we came up with. I did all of the artwork on each one of the instruments, and got the negative, put the color on the negative and mounted 'em under black glass. I was still assembling those things on one side of the bridge when they were shooting the other side...." [2] Jefferies added later, "Several of the instruments that we had in the bridge were very complicated-looking wiring diagrams. They were actually from the weapons bay on the B-58, a supersonic bomber; I got hold of the manual on the weapons pod. Any symbol that was known we painted out, then we turned it upside down and had a negative made, put it under the black glass, and backlit it." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 22) Jefferies initially intended to present an early equivalent to a touch-screen console, which he called "magic jukebox stuff." "For the displays, what I was after was a perfectly plain black panel that would light up when you touched a spot. But the lights were so strong that we didn't dare leave them on for more than a matter of seconds, or it would melt the unit under it!" In the end, the effect, envisioned as a film sandwiched between two pieces of glass and backlit, did not quite work out as well as Jefferies had intended, and he had to make do with a more static version for the computer readout displays and the overhead projection screens. And even then, later special effects staffer Jim Rugg had to jump in frequently and kill the switches to avoid consoles burning out. "I wanted to get a cumulative effect with the lights rather than indiscriminate blinking: what I was trying to do without getting into all kinds of expensive stuff was get an amber, two ambers, three ambers, four ambers and then a red or something like that. All of the instrumentation I did personally: I did the artwork, had it shot, got the negative, put the color in the negative, and then sandwiched it under that black glass," Jefferies elaborated. (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 22) Another graphics display intent, the overhead screens constantly flickering with continuously changing data displays to be realized with a back-rigged slide projector, had to be abandoned for rather mundane reasons. Union regulations stipulated that each of the projectors had to be manually operated by an individual projectionist. A costly proposition from a budgetary standpoint, it was decided to replace the screens with static painted panels, save for those specific instances when the script required a screen to be used, typically on the science station. (The Art of Star Trek, p. 10)

The numerous bright light bulbs on the bridge set had very modest origins, as was later recalled by John Jefferies (who remained to also work on the final construction of the bridge set, though he had to do this at nights, as he was working on movies by day [3]). "For the jewel lights on the consoles and the bridge and anywhere we needed a panel that had lights behind it," he explained, "ice-trays were used that were tipped of on edge to put resin in, put some color in, you know." To that, later Set Decorator John Dwyer has added, "That was buttons and light. If we wanted to light them up, we'd drill a hole, put a piece of plastic on top, put a light in the back of it." (TOS Season 2 DVD-special feature, "Designing the Final Frontier")

Build and first production use of the original configuration bridge[]

|

|

The conceived eight wild sections, each of which were capable of being moved in and out to allow camera crews access to shoot the bridge at various angles, consisted of the turbolift, the main viewing screen and six bridge work stations, each with two overhead screens. Constructed at more cost-effective straight angles, the sections, when assembled, formed an octagon, approximating the circular form as originally envisioned. Construction of the set was started in November 1964 on Desilu Culver Stage 15 at the Culver City location, which constituted the former De Mille Studios and currently the Culver Studios. The electric wiring alone took hundreds of man-hours to complete and, when completed, all instrumentation could either be operated from an off-stage central panel, or individually operated by performers from their work stations. Jefferies' "special effects man", assigned to the production by Jim Paisley and responsible for the electronics, was Joe Lombardi, Roddenberry's "genius gadgeteer and electrician and jack-of-all-trades" of his 25 August 1964 memo. The bridge set was executed in a somewhat bluish-gray monochromatic color setting at the behest of "The Cage" director Robert Butler, who wanted the sets to reflect the dark and moody script of the pilot. When completed, the original set was reportedly constructed at a cost of approximately US$60,000, or close to ten percent of the pilot's total production costs of US$616,000, and took six weeks to complete from conception to construction. (The Making of Star Trek, pp. 102 & 106; These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, pp. 36-37, 56-58) Filming, originally slated to start on 30 November, on the new bridge set started for the first time on 2 December 1964, and principal photography was finished the following day. The circular novelty of the bridge design caused director Butler to be less than enamored with the set. "I remember pleading to get some vertical structures in the bridge, because that was just too 'clean' for me. I [tried] like hell to shake up that bridge, and it fell on deaf ears... Anytime I get into a 'clean' situation, I start grinding my teeth. And Star Trek was a 'clean' situation." (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, p. 57)

Once the first pilot episode was in the can, the bridge set was left standing on the Culver stage, as the unusual situation occurred that a second pilot episode was considered. Once that pilot, "Where No Man Has Gone Before", was approved, live returned to the bridge set, though there were some differences. Matt Jefferies recalled, "Some things didn't work. At some time Gene wanted a small monitor viewer for each chair. There was one on a gooseneck arm of the captain's chair, and I hated the hell out of it. It just didn't seem logical. We got rid off it because it got in the way of the camera, and sometimes in a scene if we weren't careful it would jump; it would be here one second and there the next." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 22) There were other changes as well, aside from the removal of the "gooseneck" monitors from the captain's chair, most notably the more pronounced color scheme, with starkly contrasting blacks and reds added to the railings, turbolift doors and navigation console. Roddenberry's original "genius gadgeteer and electrician and jack-of-all-trades", Lombardi, was not available for this production, due to obligations elsewhere on the Desilu lot. In his stead, outside contractor Bob Overbeck was hired for the mechanical and special effects. While Overbeck has never again worked afterwards for the Star Trek franchise, he does hold the distinction of providing the very first bridge console explosions. First unit bridge scenes were shot from 20 July through 23 July, with additional second unit photography, not needing the principal cast, shot on 29 July 1965. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, pp. 87, 90)

Refurbishment and regular production use of the original configuration bridge[]

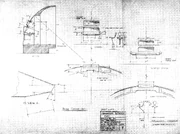

Jefferies' refined bridge floor plan

After the second pilot was shot, the bridge set, along with the others were stored outside while the studio pondered the fate of he series. This of course had detrimental effects on the set when the series was given a go-ahead, as Jefferies recollected, "We had to move from the Culver City lot to the Grower lot [then adjacent to, and now part of, Paramount]. The bridge and about 20 feet of one of side of the corridor, and the lights from the floor of the transporter room, were just about the only things that came over here. That's all that was usable. The bridge had suffered to some extent because it had been stored outdoors and covered with tarp, and condensation and moisture had caused some problems." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 23) As a result, the bridge set had to be largely reconstructed. While costly, this turned out to be a fortuitous circumstance, as Associate Producer Robert H. Justman clarified, "But first, we had to accomplish the move. All the so-called permanent, starship sets had to be removed from Culver City and transported to their new home in Hollywood. Unfortunately, we had discovered during filming that these "permanent" sets were much too permanent. Ideally, motion picture sets are designed to be flexible. In order to accommodate whatever camera angles are needed, walls are usually designed to be removable or "wild," so that there will be enough room for the cameras, floor lights, grip equipment, and shooting crew. The Enterprise set used in the pilots looked great on film, but it was awkward to work in. Not enough of it was wild, and this lack of flexibility slowed our progress to a crawl. If we were going to make our show in six days each. I knew we had to make some big changes. After the sets were trucked over, I asked Matt to make every section of the Enterprise bridge really wild. Matt and Roy Long, his construction supervisor, went to work." (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, pp. 113-114)

The "molded fiberglass" casts Jefferies had referred to earlier, now really came into their own by becoming parts of the so-called "wild-sets" when the bridge was rebuilt for the regular series production and as far as Justman was concerned they were a God-send, "The other untouchable set was the bridge. My experience with both pilots convinced me it should be filmable from any angle, allowing us to pull out any module quickly without compromising the intricate wiring for all the other consoles. To do This, Matt Jefferies and Roy Long made a mold from one of the heavy, all-wood bridge consoles and used it to cast enough lightweight plastic resin and fiberglass copies for the entire set. Now our grips could quickly pull or reset them for any camera setup that the director chose. Set operations became much more efficient thanks to Matt and STAR TREK 's unsung hero, studio construction chief Roy Long." Continuing, Justman went further into the details of the advantages of having wild-sets, "Next, special effects wizard Jim Rugg and his crew wired every console so that any section could be removed without wreaking havoc upon the electronics in the remaining ones (This monumental job took many weeks of work, and only became operational shortly before we filmed our very first episode, "The Corbomite Maneuver"). While the bridge was now a really wild set, the choice of camera angles was somewhat restricted because the Enterprise miniature had to be photographed flying left to right on screen. This was because the ship's running lights and illuminated power pods were fed by an umbilical which entered the fuselage on the off-camera port side. Therefore, the major angles inside the bridge had to reflect this screen direction. Next time you watch STAR TREK, note that the ship almost always travels from camera left to camera right." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 17, p. 13) A noticeable difference was that instead of the original eight wild sets, it was decided to have now ten wild sets, in order to provide directors with additional camera angles to somewhat compensate for the restriction Justman mentioned and with the added advantage that the bridge set now approximated a circular form even closer.

|

|

Hugely important was that each separate section was rewired independently, so that the electronics on each separate section continued to work even when one or more sections were pulled out of the set. Instead of assigning a Desilu staffer to the project, a dedicated special effects artist was hired now that Star Trek had become a regular series, Jim Rugg, and it was he who entirely re-rigged the electronics of each bridge section, enabling each of them to operate independently. (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, p. 109) The Grower lot Jefferies had referred to was actually Paramount Stage 9, where the bridge set was located throughout its remainder as production asset for the Original Series. How innovative the set was at the time was evidenced by the remarks of the early episode "The Man Trap" writer George Clayton Johnson made when he visited the freshly raised interior Enterprise standing sets, "It was very weird. They had it all on wheels so that they could take sections out like a segment of pie. They could whip out a wall and stick a camera in there and shoot the bridge. Then they would put that wall back in place and take another segment of the pie out an reposition the camera. So they were able to move the cameras pretty freely because they had made the bridge in six or eight fairly large chunks that were light enough to move and that would clamp back together. It was really quite ingenious to watch." The refurbished bridge set was put through its regular series paces for the first time on 25 May 1966 for the episode "The Corbomite Maneuver". (These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, 1st ed, pp. 110, 123)

Production reuses of the original configuration bridge set[]

During the production of the Original Series, the Enterprise bridge set was called upon to stand in as the bridge of another vessel on three separate occasions. As they in all three cases concerned class sisters of Enterprise no refurbishment was necessary, which enabled the set to be used as it was, though care had to be taken to avoid Enterprise's dedication plaque being seen on-screen. This was in the case of USS Exeter achieved by simply covering up the plaque with a board painted in a color that matched that of the port-side bulkhead it was attached to, whereas deliberate camera angles avoided the plaque altogether in the cases of USS Lexington (where only a single camera angle was used) and USS Defiant.

Defiant's bridge set was faithfully recreated as itself for Star Trek: Enterprise in 2005 with its very own dedication plaque, which incidentally provided firm visual confirmation in canon that Enterprise too belonged to the Constitution-class, the "Starship-class" designation on its dedication plaque notwithstanding (see: main article).

Legacy[]

Jefferies' taking a cue from the Navy's operating procedures had a real life reciprocated effect as the Navy took a cue form his bridge design, as he related in 1987, "We had some talks with the U.S. Navy during the third year of STAR TREK and they wanted to know the theory behind the bridge – the slopes and various angles... We explained it to them and I gave them a full-sized vertical section. There is a letter in the file stating that the Navy did use that as a basis for one of their major communications centers." (Cinefantastique, Vol 17 #2, p. 29) On a later occasion he has added, "Gene called me one day and said there were some navy officers that wanted information on the bridge and why we did it the way we did. So they came in – a commander and a lieutenant – and we treated them to lunch, and I showed them the drawing and pulled the blueprints for them, and they got to look at he bridge itself. We got a nice letter the following week thanking us, and about a year later another thank-you letter saying that the information had led to the design of a new master communications center at NAS San Diego. And they would like to invite me down to see it, but unfortunately it was classified. I didn't bother to tell them that I still had an ultra top secret clearance from work I had done when I was in Washington before coming out here!". (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 11, p. 21)

USS Enterprise bridge, animated style

When Star Trek: The Animated Series went into production in 1973, the basic design and layout of the bridge as established in the Original Series was adhered to. There was however, a noticeable addition. Producer Gene Roddenberry requested that a second turbolift was added on the bridge in response to fan questions asking what the crew would do if the hitherto one turbolift got stuck. The new lift was located next to the main viewscreen on the forward port side. Having made the request when the production was just started up, this somewhat unusual location was necessitated as the animation cells showing the aft side of the bridge were already made, which made it more expedient to adapt a cell of the far less frequently seen port front side by replacing a bulkhead with the lift, thereby avoiding noticeable and obvious continuity issues. The forward lift was only seen in a few episodes, usually with its doors closed, starting with the fifth episode, "More Tribbles, More Troubles". The lift with its doors open was only seen twice, in "More Tribbles, More Troubles" and "The Terratin Incident". (The Art of Star Trek, p. 46)

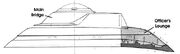

Original Series-inspired bridge

Around the time the Animated Series was being aired, Jefferies himself, not involved with that series, was working in pre-production as production designer for legendary science fiction movie maker George Pal for his proposed War of the Worlds television series, an intended follow-up of his classic 1953 Paramount Pictures War of the Worlds movie. For the project he conceived a "hero" ship, the "hyperspace carrier" Pegasus, itself an offshoot of the abandoned 1968 Strategic Space Command concept for model kit company AMT. For that ship, Jefferies created bridge concept art work that had a more than passing resemblance to the one he created for the Original Series, with an element added, an access well, reconsidered later on for an early bridge variant for the Star Trek live-action follow-up production, four years later. Ultimately though, the War of the Worlds television project never came to fruition. [4](X)

Original configuration bridge production use recreations[]

It was not only fandom that was fascinated with the original bridge configuration but, as it turned out, later incarnations of Star Trek in the form of, until then, closet production staff fans as well. On three occasions the original configuration bridge was recreated in full, or in part, for actual use in modern Star Trek television spin-off productions.

"Relics"[]

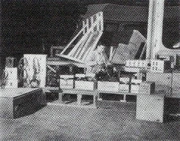

The Enterprise bridge set pieces built for "Relics"

The next time the original bridge was seen by television audiences was in the sixth season episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, "Relics", written by original series fan Ronald D. Moore, in which Captain Montgomery Scott finds himself unexpectedly in the 24th century. In the episode, feeling out of place, Scotty visits the holodeck on the USS Enterprise-D to reminisce on days past. The setting he choose was the bridge of his old ship.

It was Moore, who suggested recreating the bridge as a set, having already done so a year earlier for the USS Bozeman in "Cause And Effect", but like on that occasion, the idea was initially nixed for budgetary reasons. (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, 3rd ed., p. 219) Michael Piller recalled, "We had Scotty and then Ron came up with this wonderful idea of recreating the old starship. It was an interesting dilemma because it was a very expensive proposition. It was actually cut out after the first meeting with Rick and the production people." (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 23) Yet, this time around, Moore was not ready to let go of the idea, and continued to look into the possibilities. Ultimately, after Piller suggested renting fan-built replicas or maquettes, it was Production Designer Richard James who came up with a cost effective suggestion, of building only a wedged-shaped part of the bridge and have it composited with a blue screen matte using suitable film elements from the old series as background, if such footage could be found. (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, 3rd ed., p. 219) "My initial reaction was what we wound up doing," James elaborated, "I said if they could find a clip of the original bridge of the Enterprise, then we could take that film clip and do blue screen and I could just build a piece of the original to shoot the actors against. When Scotty walks in and sees an empty bridge, what he sees is a blue screen. Then I explained that we could take the actor across the blue screen and pick him up walking into the frame again and he'd be against the real set at that point." Supervising Producer David Livingston, who originally vetoed the construction of the set, was elated at James' suggestion, "I said we couldn't build the bridge. I'm sure I did. If I didn't, I should have. But that's when Richard brought up looking at the original show and seeing if we can get "stock footage" off of it. That was like manna from heaven." (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 25)

That suitable Original Series footage was the footage of the empty bridge seen in the background, when Scotty entered the holodeck. It was Visual Effects Producer Dan Curry, like Moore a closet Original Series fan, who remembered the empty bridge scene of the original Enterprise from The Original Series episode "This Side of Paradise". (Star Trek: The Next Generation 365, p. 274) The scene, color corrected and enhanced, was looped into the longer footage as eventually featured in the episode. Due to the "looping" of the scene, and blue screening it behind Scotty performer James Doohan, the small, wedge-shaped part of the set, though somewhat cramped, served exceptionally well, as it could be used to represent different parts of the bridge by slightly redressing it and using different camera angles. Ironically, Doohan did not appear in the episode from which the footage was taken. The shot of the original viewscreen (with no one sitting at the helm/navigation console) was recycled from "The Mark of Gideon". (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, 3rd ed., p. 219)

That there was only a small cramped part of the bridge built came as a nasty surprise to first time Star Trek director Alex Singer, who had expected to work with a full bridge set, "I didn't see how they were going to do it. I assumed they had a complete bridge. When I was told they had one third of one part of it, I had to put on my thinking cap. I'd like to feel I'm a filmmaker and that given anything to work with I probably can make it work, if it's possible. No challenge has been as peculiar as this one, though. We had a monitor on the set and I worked from the monitor and I kept reliving the old STAR TREK deck, and I was never on it as a director. It's not memorable to me, but all of a sudden I'm living in a place and I don't even have it in front of me to deal with so the business of creating it was to me an enormous cinematic challenge. I had with me an art director and a visual effects director who with their knowledge and sophistication could pace me very comfortably." Richard James, Singer's art director, had to lay out the effects procedure for Singer, "I explained to Alex that we could take the actor across the blue screen and then pick him up walking into the frame again and he'd be against the real set at that point." (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 26)

When Scotty first enters the holodeck, there is another red alert light visible behind him that was not present on the original bridge set. In terms of filming, helping out Singer with his shots, the set designers removed the dedication plaque from the turbolift foyer to create the illusion of a different part of the bridge, thereby also saving money on building more of the set, which, as what was called a "wild set", was mobile, allowing it to be moved around for different angles. Additionally, in order to further enhance the illusion, the graphics on the bridge monitors were replaced when another angle of the bridge was deemed necessary. James assured Singer, "I told him it will look like it's on the other side of the set so it will give the illusion that we literally did the full Enterprise bridge of the original series." (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 26)

The replicas of the captain's chair and helm, and navigational console were built by Steve Horch for convention purposes and slated to appear in the 1993 Star Trek Earth Tour traveling exhibition. [5] Discovered by Michael Okuda shortly before the start of the tour, they were rented for the recreation of the original bridge, and from a budgetary standpoint were instrumental in pulling off the recreation (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, 3rd ed., p. 219), Okuda having flat-out stated, "If not for Steve Horch, we would not have that scene.". (Star Trek: The Next Generation 365, p. 274) Returned to Horch after use, the now bona-fide screen-used set pieces, together with the by the studio built wedge-shaped bridge panel, continued their existence as tour displays.

"Relics", once approved, was quickly realized by the studio to be of singular emotional importance to Original Series fans, due to the visual reconnection with that series within the Next Generation framework, despite the earlier appearances of Sarek and Spock. In order to give them what they wanted, the studio somewhat relaxed the "not hiring fans as production staff proviso" by allowing those who already were to come "out of the closet", as the episode writer Ron Moore, being one himself, has put it by stating, "A lot of people put in a lot of extra effort and didn't get paid for it and put in a lot of extra hours to make that possible and just bit the bullet because they wanted to do the scene." Production staff fans of the Original Series, aside from Moore, Curry, Naren Shankar, and Wendy Neuss, like Okuda, Doug Drexler, and Greg Jein (providing several screen-used Original Series captain's chair's buttons given to him by Original Series special effects technician Jim Rugg, for use in the episode), poured their hearts and souls into the making of the episode's Scotty bridge scene. (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 26) Realizing the scrutiny the episode would be under, Moore additionally acknowledged, "The people in the production department put in a lot of extra hours and a lot of free work because they really wanted it to look good. They really wanted to sweat the details because they knew everyone was going to be watching us – it's the kind of thing you better not screw up or you're going to be hearing about every little thing!" (Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, 3rd ed., p. 219)

The set proved to be a powerful visual reconnection with the Original Series. While the episode was in production a slew of Star Trek alumni visited the set, many of whom were not involved with the production of the episode but had worked on the Original Series. Visiting dignitaries included Robert Justman (who had been a producer on the Original Series and The Next Generation, but had left the franchise five years earlier), Walter Koenig (Chekov), Majel Barrett (Roddenberry's widow, who also provided the computer's voice for the episode), and Paula Block, among many others. Michael Okuda took it upon himself to make sure that the visiting (ex-)staffers had the opportunity to visit the set. (Star Trek: The Next Generation 365, p. 274) When it was writer Moore's turn to visit the set, it too proved to be an emotional experience for the avid fan, "Michael Okuda gave me a call and said you've got to come down and see this before it's shot. I went down and sat there and got tears in my eyes. I sat in the captain's chair because it was so real. And then the day they were shooting I went down, and there was Jimmy on the bridge. And then Majel came in to say "hi". And then Bob Justman walked in. He came over and watched the scene and said some very nice things to me about the writing. It was like a time warp standing on the bridge of the Enterprise with Bob Justman and Majel. I remember we were talking and when he first walked in he had his back to the set and he turned around and went, "Oh, my God," and he just looked at it. It was such an accurate re-creation he couldn't believe it." Moore also stated that Justman detected that the carpet color was off from that of the original, but once lit properly it blended in seamlessly with that of the original footage. (Cinefantastique, Vol. 24, issue 3/4, p. 27)

Refit-configuration bridge[]

A set of similar design was built and used to serve as the bridges of the Enterprise and Enterprise-A in the first six Star Trek films, though it was frequently redressed to meet the particular tastes of a director and/or production designer.

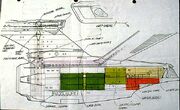

Making its debut in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the redesigned bridge was actually designed and largely constructed in 1977 for the film's immediate predecessor, the planned television project Star Trek: Phase II. Redesign work was started in early June 1977 by the original bridge designer Matt Jefferies, who had agreed to serve on the television production as a temporary "Technical Advisor" only. (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, pp. 23-27) Remarkably, Jefferies started out with revisiting Pato Guzman's more futuristic looking original Control Room concept in quite some detail, also including his Pegasus bridge inspired "access well" he had conceived a few years earlier for the aforementioned abandoned War of the Worlds project. Yet, after Joe Jennings, Jefferies' second season assistant on the Original Series, came aboard a few days later on his recommendation as art director, it was quickly decided to stick with the classical lines as established for the original bridge and limiting themselves to modernizing the look. What noticeably remained however, was a true circular form, as well as a second turbolift as established in the Animated Series. Graphic Artist Lee Cole joined the two men the subsequent month lending her input to the redesign, most notably that of the bridge instrumentation and their lay-out, and drawing up the set construction blueprints. (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, p. 28)

Construction on the bridge set was started on Paramount Stage 9 on 25 July 1977 under the auspices of another Original Series veteran, brought back on Jefferies' recommendation, Special Effects artist Jim Rugg, who was answerable to Jennings. Phase II Producer Robert Goodwin reported in a progress memo to Gene Roddenberry dated 3 August 1977:

"The basic layout of the Enterprise set has been drawn. Work is being concentrated on the two most complicated sections of the set, the bridge and the engine room. The basic shell of the bridge has been approved in design and is currently being built. Platforming should be done by the end of next week. The molding is in construction for our plastic forms, which will cover the wall units. It will approximately a week and a half before the molds are finished and at that point we will begin casting one section a day. (There are 12 sections in the bridge, plus we will be making 6 extra sections, to be used as needed for explosions, special effects, etc.) The shell should be completed by the end of August. At the same time, Matt Jefferies, Joe Jennings and special-effects man Jim Rugg are at work designing and researching new types of instrumentation that will be used within the bridge, including new kinds of computer graphic displays, touch control switches, etc. (...) Joe Jennings and Matt Jefferies are researching new materials that can be used in forms of plastics and metals that were not available to us previously." (The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, pp. 36-37)

|

|

|

|

The set construction crew wasted no time, as Goodwin was able to report in a follow-up progress report six days later, "Work is continuing on stage 9 with the construction of the Enterprise set. All frames and platforms have been built for the bridge. The plaster mold is almost complete and on Monday we will start casting the plastic skins. There are 12 sections. We will cast 12 skins plus 6 extras. (...) Joe has now drawings of the weapons defense station, which are ready for you to see. Once he gets your approval, he will put working drawings out and we can start construction on that particular station. By Thursday he will have several sketches of proposals for the consoles of the other stations. Mark Tanz, along with Jim Rugg is doing research into various computers and instrument panels etc., which can be used in conjunction with these consoles." The following day Production Illustrator Mike Minor was hired, and one of his first assignments was to produce concept art of the bridge to give producers and studio executives a feel for the completed look of the bridge. Interestingly, Minor located the second turbolift where the Animated Series had it located. (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, p. 37, color inset) In a subsequent 8 September 1977 progress memo, Goodwin became aware of a problem that had bedeviled Robert Justman and his film crew on the Original Series bridge set, "So far we have pulled five skins of the bridge and by next week we will be finished with all twelve skins. The skins are coming off better than we'd hoped for. The only possible problem involved is an echo effects in certain portions of the set, but Joe Jennings has already arranged with Glen Glenn Sound to go over the set and eliminate any of those problems before we start production." (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, p. 43) With the ambient sound problem looked into, construction went otherwise smoothly and encountered no serious other setbacks, as was evidenced in Goodwin's last Phase II production progress memo of 21 October 1977, when he reported that basic construction and painting was completed and that, "Just about all the consoles have been mounted in the bridge and work is going forward on the instrumentation. The consoles for the Engine Room have also been completed. There are two set designers at work finishing the instrumentation drawings, which are immediately given to Jim Rugg, who is putting all available men to work." (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, p. 52)

Then, on 21 November 1977, the executive decision to upgrade Phase II to a major theatrical feature was disseminated through the lower production echelons, and production on Phase II was suspended in order to ascertain the requirements for a motion picture production, including construction on the bridge set, which was nearing completion. (The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, p. 47) On 12 December 1977 Post-production Supervisor Paul Rabwin inspected the sets to see see if they would hold up in big-screen resolution and deemed them salvageable, albeit with additional upgrading and detailing. To this end he had director Robert Collins and cameraman Bruce Logan start shooting test footage and lens tests of the sets on this date, but now with anamorphic lenses, required for wide-screen films, to get a feel of how these sets will translate on theater screens. Shooting of this test footage lasted for two weeks, and after it was finished the set was abandoned for two months while the producers were gearing up for the production of the film. (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, pp. 67, 73, color inset) When the production was halted, construction costs for the bridge set had just passed the US$1 million dollar mark. (Starlog, issue 27, p. 26)

Veterans Matt Jefferies and Jim Rugg by that time had already left the production earlier in November, the former to return to his regular job. Jefferies later sold his bridge design art, including that for the Original Series, in the aforementioned The Star Trek Auction of 12 December 2001. He did not retain ownership of his two, Guzman inspired, early June color bridge designs sketches, which turned up at auction separately later on. The Guzman inspired sketch turned up at Profiles' Hollywood Memorabilia Auction 37 where as Lot 602 it sold on 9 October 2009 for US$2,750 (excluding buyer's premium), having been originally estimated at US$3,000-$5,000.[6] Discovered on the back of one of Jefferies' aviation paintings, the auction description assumed it was done for the Original Series due to its close resemblance to Guzman's original painting. This was dispelled when the blueprint of the Guzman inspired bridge turned up two years later at auction as lot 1449 in Profiles' Hollywood Auction 44, estimated at US$2,000-$3,000, where it sold on 11 May 2011 for US2,360 (including buyer's premium). [7] One of Minor's bridge concept art pieces, the in red tones aft view piece featured below, was after production had wrapped gifted to notable fan Bjo Trimble in recognition for her services to the franchise. She auctioned off her piece in Profile's The Ultimate Sci-Fi Auction of 26 April 2003 as lot 153 for US$1,100 (excluding buyer's premium), having been originally estimated at US$1,500-$2,000.[8](X)

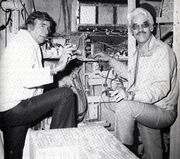

Abel directing the bridge set test footage

Life shortly returned in February 1978 to the abandoned and near-complete bridge set, when Robert Abel of Robert Abel & Associates, the company recently contracted for the visual effects, shot test footage in order to ascertain effects requirements, with extras still clad in Original Series/Phase II uniforms. To this end, an internal document, "Enterprise" Flight Manual, still reflecting the Phase II bridge configuration, was drawn up by Cole and Jennings, intended to instruct the stage effects technicians on wiring up all of the work station's control panel backlits, working switches and indicator lights as well as giving performers basic button-pushing lessons, was distributed among the various departments that month, prior to shooting. The manual was a few months later updated to reflect the design changes that were implemented after April. (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, pp. 78, 104-108)

In April 1978, Harold Michelson was brought in by Director Robert Wise as production designer, replacing Joe Jennings as head of the art department. Michelson was responsible to perform redesigns on the Phase II sets in their various states of completion for their motion picture use. The first set he tackled was that of the bridge, and to this end he had a production illustrator, who signed his work with Hersey (nothing else is known about this artist, as he was not credited for his work), translate Minor's artists impressions into more crisp, businesslike non-artistic black and white pencil perspective drawings, already incorporating some of the design changes Michelson had in mind. He began by eliminating the original plastic bubble, representing Chekov's weapons station, already grafted onto a section of the bridge wall. The bubble was supposed to feature neon-lighted cross hairs, with Chekov manipulating them to get a target lock, while he looked out into space (incidentally, the bubble design was remarkably reminiscent of Roddenberry's original "revolving globe" proposition of 25 August 1964). The round hole was covered up with various technical readouts. Wise requested that Chekov would face the main screen, which was difficult to realize on a circular bridge. Yet there was one corner on the bridge somewhat differently sculpted, for reasons that nobody really knew – production staffers jokingly speculated that it was the bridge's "head", conspicuously missing in the Original Series – and Michelson had Minor design a new corner for this area, which became the weapons station alcove. A noticeable novelty was the addition for the first time of a bridge ceiling, inspired by the look of a jet engine fan, which Minor also designed. According to Minor it gave the bridge a more Human touch, as the ceiling bubble was intended to be a piece of equipment which told the captain the state of the ship's attitude, even though in real space there was no right or left or up and down. Another change Michelson made was the design of the chairs and the captain's chair, from the simple pedestal swivel seats and boxlike captain's chair, reminiscent of the ones used in the Original Series, to girdle clad, multifaceted, ergonomic seats with automatic, switch operated, bracing devises, for which Set Decorator Linda DeScenna concurrently lent a hand in designing. (The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, pp. 85-88)

When redesigning the bridge instrumentation of the refit-Constitution-class for the Motion Picture, Graphic Designer Lee Cole recalled, "Our original designs for Star Trek I were much more detailed and interesting. Then Gene Roddenberry said, "I want it really plain to try to be futuristic. Cut out all this detail, and simplify things." We did that, but it got a little too plain, I think. It was kind of beige." (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 3, Issue 5, p. 67) Elaborating, she has added, "We did a lot of research in getting the bridge together. We talked to a lot of scientists about what advancements might occur by the 23rd century. But despite our research and our contact with all these brilliant minds, we often couldn't use our findings for the film. I had originally designed the Enterprise consoles to be entirely smooth. The were to be heat sensitive, so a crew member could execute his or her duties by simply waving a hand over the console. No buttons or anything would protrude from the surface." Yet, upon the upgrade to a movie, the notion was reverted, "But Robert Wise said, and rightly so, that those sort of designs just wouldn't be dramatic. In his director's role he explained that, in a really dramatic sense when Sulu's hand is grasping at this lever in an attempt to save the ship, it wouldn't be very exciting not to have a lever there for him to grasp. So we had to violate some scientific principles in order to come up with some big knobs and levers." (Future Life, issue 17, p. 45) Cole's "entirely smooth" consoles, essentially the same proposition Jefferies had made one-and-a-half decade earlier and which was revisited for Phase II, ultimately did turn up a decade later as the touch screen interfaces in Star Trek: The Next Generation.

The revisions of the bridge set were finished on time to meet the shooting schedule, which started on 7 August 1978 with a bridge scene, but it did add an additional US$205,000 to the hefty US$1 million dollar already incurred, making it the most expensive set, as it was for its predecessor and would be for its successors in the Star Trek franchise. (The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, p. 95)

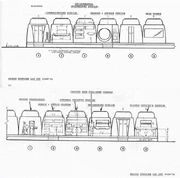

| The refit Constitution-class bridge set as featured in... | |

| |

|

|

|

|

Joe Jennings was the production designer on the second outing in the film franchise, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Due to strict budget limitations, no funding for radical redesigns was available, and the bridge set was pretty much reused as it was for its previous film outing. To facilitate the vision director Nicholas Meyer had in mind for the film, relatively simple and inexpensive means of redressing were used to give the bridge a more sleek, utilitarian and nautical feel. These included a repaint in darker colors, different lighting in reddish hues, and adding new bridge console graphics predominantly executed in contrasting green. There were modifications to the bridge set electronics. At Producer Robert Sallin's insistence, the film projectors used in the previous film to put graphics on the screens around the bridge, were replaced with especially adapted television monitors that did not strobe on screen. Most of the film of the display graphics from the first movie were transferred to video so that the majority of the graphics stayed the same. New, animated ones, such as the targeting graphics displays and essentially early CGI effects, were constructed at Evans & Sutherland. Jennings had to install a series of fans in order to cool the many built-in electronics, which started to melt the instrument panels when kept on too long. Additional electronics modifications were performed, as Jennings clarified, not entirely without its own set of drawbacks, "That bridge had no visual controls whatsoever. When everything was turned of, it was absolutely shiny, blank, black; everything was activated by proximity switches. All the actor had to do was just wiggle his fingers over the top of it and the lights would come on and start doing their winky-blinkies. Well, sometimes they set the proximity switches up too high, and somebody would walk by'em and the whole panel would turn on" (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 3, Issue 5, p. 67) The film marked the first and only time that the construction of a bridge set (i.e. in wedge shaped sections) was featured in a scene. In its role as the Mark IV bridge simulator, the main view screen section was pulled out to allow Admiral Kirk access to the simulator at the end of the Kobayashi Maru scenario, featured at the beginning of the film. The studio background was skillfully camouflaged by smoke and strong counter-light flooding for the scene. Virtually produced back-to-back, the bridge set was not further modified for its subsequent film outing, The Search for Spock.

William Shatner, director on Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, had been so impressed with Herman Zimmerman's work on Star Trek: The Next Generation as production designer, that he hired Zimmerman to upgrade the Enterprise interiors for the film. Hence, the upgraded bridge from the film resembled the bright atmosphere portrayed in The Next Generation, although strictly speaking, his predecessor Jack T. Collis had already applied the brightened atmosphere, in order to reflect the lighter tone of the film as set by director Leonard Nimoy, on the bridge at the end in the previous film outing, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, by repainting the set without otherwise modifying it, save for one feature; The graphics on the bridge console displays were replaced with new ones by Mike Okuda in his first motion picture assignment. Decades later Zimmerman later jokingly commented after seeing the film, considered so flawed by so many, "After the show was over, I was pretty sure I would never do another!" (The Art of Star Trek, p. 249; Star Trek: 45 Years of Designing the Future) For The Final Frontier, while the bright color scheme remained the same, the bridge stations received an upgrade in the form of wall covering computer console displays, for which Okuda, now firmly established as Star Trek's resident scenic artist, provided his famed okudagrams, which actually could be considered somewhat of a continuity error.

Production reuses of the refit-configuration bridge set[]

Aside from representing the main bridge of the refit-Constitution-class, the set or parts of it also doubled was also used or redressed as various locations including the bridge of several other Federation vessels.

When production of Star Trek: The Next Generation began, it took over Paramount Stage 9 and the Original Series movie sets it contained, including the bridge set, and modified or redressed them for the series. The bridge set was modified to serve as as the battle bridge of the Enteprise-D for the series pilot and continued to be redressed for various uses throughout the series. Although early stage plans for the series dated March 5, 1987 contemplated the movie bridge to be retained as it was, only a small amount of the original bridge set was ultimately retained.

The original bridge set was a full circle (made up of 12 wall sections) with a raised outer level surrounding a circular lower level where the navigational console was. The battle bridge set retained a portion of the raised section only at the rear of the bridge, about the width of the five rear wall sections. The three center wall sections were left intact including the two turbolift doors with distinctive wall recesses that flared at the top, and the panel cutouts in the center wall. The outer two sections were were either replaced or modified to remove the work stations.

Most of the rest of the bridge was replaced. New straight walls running from the ends of the curved rear wall panels narrowed toward the new viewscreen, creating a more triangular shape. Each of these walls had a one-piece sliding door. The port door led to a new auxiliary ready room. Vertical struts that had been added between each of the rear wall panels for the set's brief appearance in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home were replaced with differently-shaped struts that were taller and slightly wider. The railings between the upper and lower level were changed. Three forward-facing TNG-style consoles were erected on the upper level in place of having stations built into the walls. The captain's chair, along with the Conn and Ops consoles and chairs were of the same style as those from the Enterprise-D main bridge. New turbolifts (a standard Galaxy-class turbolift on the port side, and a rectangular emergency turbolift to the bridge at starboard) were added to the set.

This version of the set appeared twice as the battle bridge during the first season with minimal changes. It also acted as the bridge of the USS Stargazer in TNG: "The Battle", with the original movie-era turbolift, graphics, and chairs returned to the set.

Originally constructed in 1977, the refit-Constitution-class bridge set was the longest-lived standing set in the history of the live-action Star Trek franchise. (Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition)-special feature, "text commentary"; Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion, ? ed., p. ? individual episode entries; Star Trek Encyclopedia, individual ship entries). However, at some point prior to filming Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the venerable set was virtually destroyed in a freak weather event while being temporarily stored on the outside studio parking lot in order to make room for other sets. The timing is disputed, and some sources say this occurred shortly after the bridge scenes were filmed for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier in late 1988. Little could be salvaged save for some parts such as the two turbolifts and the bridge platforms. (Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (Special Edition) DVD-special feature, "text commentary"[1])

The original battle bridge set had a domed ceiling that began just above the height of the turbolift doors. It last appeared this way as the Battle Bridge in TNG: "The Arsenal of Freedom" shot in early 1988 towards the end of the first season. Some time after, the rear wall and ceiling of the set was heavily modified or rebuilt. This may have been due to aforementioned destruction of the set, or simply as a result of portions of the set being needed for Star Trek V. The back wall was made taller, with large trapezoidal panels above the location of the rear stations. The vertical struts dividing the rear wall were replaced by different-shaped struts that only minimally protruded from the wall. The rear turbolift doors were removed leaving only the two side doors. This modification first appeared in TNG: "The Measure Of A Man" (shot in late 1988 or early 1989) in which the set was used as a courtroom and the trapezoidal panels were illuminated plain white as lighting. The set appeared twice between these two episodes, but only showing only the viewscreen wall (which was not used in Star Trek V): It appeared as the bridge of the Atlec vessel in TNG: "Unnatural Selection", and as the bridge of the of the USS Lantree in TNG: "Unnatural Selection". Later that season, in what may have been the set's next appearance, the set appeared as the geophysical laboratory in TNG: "Pen Pals". The set retained the padded rear wall of the courtroom . The trapezoid panels were fitted with LCARS graphics. Rounded recesses were built into the wall adjacent to the viewscreen, and the set was heavily redressed with props and decor items. It next appeared as the surgical bay at Starbase 515 in TNG: "Samaritan Snare", with the curved recesses remaining, and the trapezoids again lit white, this time with a grid of vertical black stripes that would be used off-and-on regularly in the set. In this appearance, the raised rear platform and railings removed to make the set a single level, and the rear wall was built out to reach the floor. The viewscreen was also temporarily replaced with a smaller monitor. The raised level and railings were returned for the room's next use as the Tactical lab in TNG: "The Emissary", and more prominent struts were once again added to the rear wall between panels. The curved recesses were also replaced with flat walls with monitors.

In its next appearance, the set was once again utilised as a Starship bridge (of the USS Hathaway). Workstations were added along the back wall below the trapezoid panels which were also given 23rd century graphics. (TNG: "Peak Performance"). The room was heavily redressed to serve as an outpost in TNG: "The Vengeance Factor", replacing the front wall with one featuring a pair of windows. In similar configuration, it acted as drafting room 5 in TNG: "Booby Trap" (and later in TNG: "Galaxy's Child"). The set next acted as the brig in several episodes (TNG: "The Hunted", "Deja Q", "The Most Toys"), Data's lab (TNG: "The Offspring"),

In the final appearance of the Battle Bridge in TNG: "The Best of Both Worlds, Part II", the new back walls resulted in the room looking notably different from its first-season appearances.

Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan

TNG: "Encounter at Farpoint", "The Arsenal of Freedom"

Second refit-configuration bridge[]

The new refit-configuration bridge

When The Undiscovered Country was greenlighted, it therefore necessitated the building of an almost-entirely new refit-configuration bridge set. Starting from Zimmermann's redesigns for The Final Frontier, but once more dressed to reflect director Meyer's earlier, more militaristic approach for The Wrath of Khan, Producer Ralph Winter commented on the rebuild, "We rebuilt it from the ground up. On this one we kept the platforms and some of the wider forms [note: as salvaged from the original refit bridge-set] and then we rebuilt everything else. We tied it together [with the other films] this time. We try to keep it as similar as possible because we are cognizant of the rules of the STAR TREK universe and the laws we have set up, but each director brings a new perspective to it. I think the new bridge is very close to the one you saw in V. You really didn't see much of it in IV, where there's only one shot aboard the Enterprise. If you looked at what was in STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE and II and III, that shifted around a lot, and the lighting and graphics have changed drastically." (Cinefantastique, Vol. 22, No. 5, p. 35) The new bridge set was again dressed by Michael Okudu with newly created okudagrams.

Production reuses of the second refit-configuration bridge set[]

Though specifically built to serve as the bridge of the Enterprise-A, the second bridge set was for the production of The Undiscovered Country actually first filmed as the bridge of the USS Excelsior as the Excelsior bridge scenes were slated before those of the Enterprise. The more modern Excelsior bridge was set apart from the older Enterprise bridge by means of reshuffling the variable wall panels as well as by borrowing the navigational/helm consoles from The Next Generation production to stand in for Excelsior's. For the cash-strapped production, the fact that a new bridge set had to be build was a fortuitous circumstance for its double-use potential, as the original, more cavernous original Excelsior bridge had been struck after the filming of Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. (Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Special Edition) DVD-special feature, "text commentary")

Like its immediate predecessor had, the second refit-configuration bridge set or parts thereof continued to double, frequently redressed, on various occasion as the bridge of several other Starfleet/Federation vessels with that of a Romulan Warbird and some non-bridge appearances to boot, its use in 1999 as the USS Equinox bridge in VOY: "Equinox" becoming its last recorded production use. Curiously, in its appearance as the bridge of the USS Bozeman, it included the trapezoidal panels (as grey recesses in which smaller LCARS panels were inset) and wall struts much like the previous set and unlike other appearances of this second set.

Jefferies tube set[]

Quite early on in the production of the regular Original Series run, the need for a dramatic device was perceived in order to emphasize particular tense, emergency moments in an episode, which the producers found in the form of a cramped internal maintenance conduit, the Jefferies tube. Executive in Charge of Production Herb Solow elaborated, "Necessity made Matt Jefferies the absolute mother of Star Trek invention. As Engineering Officer Scott gained importance, there came the need for a compact set where Scotty could feverishly work to effect emergency repairs on the ship's internal circuitry, when the preservation of the galaxy and the future of the Enterprise was in doubt. With short notice and little money, Matt designed a tall cylinder that later became known as the "Jefferies Tube". The camera could shoot straight down at Engineer Scott as he clung to the inside of the cramped set with lights flickering all around him. An assortment of bells, whistles, gongs and beeps was laid in afterward by the sound editors." (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, p. 167)

Original configuration Jefferies tube[]

Set Designer John Jefferies, the younger brother to Matt and who, with his team, had to build his brother's designs, recalled how the Original Series Jefferies tube was constructed, "It was the only part of that set that was moved on [note: meaning it was a mobile set, mounted on rollers], that was on an incline, and it was made out of a Sona Tube that we cut and expanded a little bit. Sona Tubes were large cardboard tubes that could be purchased. They were used for forming concrete and we would buy these in either eight- or ten-foot lengths and they came in many varying diameters. They ran about a half an inch thick and they were wrapped cardboard. Well, we found these marvelous for pieces of set and curved walls, because they were quick." (TOS Season 2 DVD-special feature, "Designing the Final Frontier") Robert Justman has added, "Whenever shooting scripts called for the Jefferies Tube, Matt added more dojiggers and thingamajigs to it. Since there was no space available on Stage 8 to keep the contraption set up all the time, Jefferies put his tube on wheels so it could be easily moved in whenever it became necessary for Scotty to restore "war-rp" power and save the galaxy. Again." (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, p. 168) To the cramped, at an angle inclined tube was later added a wider, vertically orientated one, with a three-sided ladder in the center, frequently seen recessed in the hallways of the Enterprise.

While Jefferies himself had endowed his design with the designation "Engineering Power Shaft", the set quickly went under the denominator "Jefferies tube" amongst the production staffers themselves as an "in-joke". Jefferies himself had indicated, "Somebody hung the name Jefferies Tube on it. It wasn't me, but the name stuck and I used it in some of my sketches!" (Star Trek: The Original Series Sketchbook, p. 72) Never elevated to canon during the Original Series – though the first recorded "official" use of the nomenclature had been the "SHOT – JEFFERIES TUBE" script reference in the draft of 14 September 1967 of "Journey to Babel" (scene 36, p. 21, where the body of Gav was stashed), though it was not heard in the episode) – the name indeed stuck and was adopted by Star Trek production staffers for every subsequent Star Trek production ever since and was expanded to the larger, more spacious service conduits as well, seen later in the franchise. Elevation into canon only came about in 1990, when the scene 58 line "Danar must have climbed the reactor core and gotten into a Jefferies tube." was spoken aloud by Lieutenant Geordi La Forge in Star Trek: The Next Generation's third season episode "The Hunted".

An annotation on Jefferies' design sketch read that he had designed the Jefferies tube for the first season episode "The Enemy Within", though it was not featured there. The entrance of the tube was first seen in that season's episode "Charlie X", whereas the interior of the tube was for the first time seen in "The Naked Time", both of which produced later, but aired before "The Enemy Within".

Nearly four decades later, in 2005, set designers on Star Trek: Enterprise recreated the cramped inclined original Jefferies tube as an USS Defiant (NCC-1764) one, for the fourth season episode "In a Mirror, Darkly, Part II". Concurrently, they dressed one of the standing NX-class sets to approximate the appearance of the original vertical one with the addition of a three-sided ladder. The vertical tube had already been recreated once before in 1996 for the Deep Space Nine fifth season 30th anniversary homage episode "Trials and Tribble-ations". The Enterprise episode though, added to canon as well, as it was established that the inclined Jefferies tube was actually an access passage to more spacious horizontally aligned overhead maintenance conduits in the original configuration Constitution-class vessels. These too, were standing Enterprise NX-01 sets, which the set decorators and designers adapted as much as possible to resemble the visual style of the Original Series, most notably by adding, or painting the existing, tubings and pipings in the bright colors as was established for that series and including the application of GNDN signage already applied in the Original Series and renowned in Star Trek lore. (ENT Season 4 DVD-special features, "Inside the 'Mirror' Episodes" & "In a Mirror, Darkly: Audio commentary")

The GNDN signage too, was an in-joke performed by John Jefferies and the team of set designers of the series, as he had explained decades later. "The plumbing and pipes in the Enterprise all had color codes and some form of nomenclature on it. That would be a series of letters and numbers and something that looked like you could tell what this pipe was on this side of the wall, as it came out of the wall. And GNDN with a number behind it and then a color code became very common throughout the Enterprise. GNDN means 'Goes nowhere, does nothing'." This became a well-known enough prank that when the Deep Space Nine crew re-built some of the old Enterprise sets for "Trials and Tribble-ations", they made sure to include a GNDN pipe. (TOS Season 2 DVD-special feature, "Designing the Final Frontier")

Jefferies' original design sketch drawing was later sold as Lot 117 in Profiles' earlier mentioned 2001 The Star Trek Auction, having had an estimate of US$200-$300.

Refit-configuration Jefferies tube[]

A spacious, horizontal Jefferies tube on the USS Enterprise-A; note the "GNDN" signage on the overhead pipings

Part of the reason why the designation "Jefferies tube" stuck was that it evolved from an in-joke to a homage, as Jefferies became revered by his production designer/art director successors on the subsequent Star Trek incarnations. Archivist Penny Juday has explained in 2002, "The Jefferies tube is used even today. The last feature [note: Star Trek Nemesis] is an example, where she took the Jefferies tube and made it really big. That's where you see the Reman Viceroy and you see Commander Riker fighting together, is inside a larger version of the Jefferies tube. So, Herman Zimmerman has made sure that the name sticks, and he has always idolized Matt and his work. And he has always tried to incorporate Matt's work and designs and to make sure that the theme is carried on into the new TV series and all of the features. Almost all the time – not in every episode of course – but when we need a crawl space, that's exactly what we use; it's always called a Jefferies tube." (TOS Season 2 DVD-special feature, "Designing the Final Frontier")