Marie Maitland

Marie Maitland | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1550 |

| Died | 1596 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Other names |

|

Marie Maitland (c. 1550[1] – 1596) was a Scottish writer and poet, a member of the Maitland family of Lethington and Thirlestane Castle, and later Lady Haltoun. Her first name is sometimes written as "Mary".

Poetry overview

[edit]

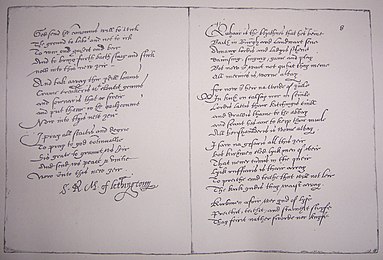

She was the transcriber of the Maitland Quarto manuscript (1586) as well as a poet in her own right.[3] The Maitland Quarto contains explicitly lesbian poetry penned by Marie, which is among the earliest Sapphic poetry in any language in Europe since the time of Sappho herself.[4] The Maitland Quarto is a significant primary source of Scottish and world LGBT history. Together with the Maitland Folio manuscript, the Maitland Quarto is one of the Maitland Manuscripts,[5] which are important sources for Scots literature of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. She recorded and preserved her father's extensive writings as his sight became increasingly poor, eventually resulting in his blindness.[1]

Early life

[edit]Marie Maitland was a daughter of Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlestane (1496–1586)[6] and Mariotta (or Margaret) Cranstoun (died 1586), the daughter of Sir Thomas Cranstoun of Corsbie, Berwickshire, Scotland.[5]

Marie had three brothers and three sisters. Her eldest brother, William Maitland of Lethington (died 1573), was Secretary to Mary, Queen of Scots.[7] Her second eldest brother was John Maitland, 1st Lord Maitland of Thirlestane (1543-1595), Lord Chancellor of Scotland.[7]

The Maitland Manuscripts

[edit]The Maitland folio and quarto manuscripts are anthologies of poems compiled and authored by the Maitland family. The manuscripts are written in Italic and Secretary hands. John Pinkerton was the first to suggest that Marie Maitland was the scribe. Her name appears twice on the titlepage of the quarto manuscript.[8] Some poems within the Maitland Quarto are written by her while others name her or are dedicated to her. These lines, in the Scots language, come from the end of Poem 49, which was almost certainly written by Marie.

And thoucht adversitie ws vex

Yit be our freindschip salbe sein

Thair is mair constancie in our sex

Than evir amang men hes bein

And though adversity us vex

Yet by our freindship shall be seen

There is more constancy in our sex

Than ever among men has been.[9]

Pamela M. King has suggested that, as one of Sir Richard's younger children, Marie could still have been living at Lethington Castle, the family home, when it was confiscated in 1571 following her brother William's arraignment for treason, and that the poem Lethington (No. 68), which she attributes to her, was a response to that experience.[10] Joanna Martin has identified Lethington as being one of the earliest of the 'country house' genre of poems.[11]

In 2021, Scottish researcher and writer Ashley Douglas and the educational charity Time for Inclusive Education developed secondary school lesson plans about the poetry of Marie Maitland and the Scotland in which she lived and wrote, which formed part of the world-first launch of LGBT inclusive education in Scotland. They also commissioned an imagined modern portrait of Marie Maitland, which is currently on display at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.[12]

Family and literary relationships

[edit]In 1586, Marie married Alexander Lauder of Haltoun. The contract was made in September.[13] Alexander Lauder was Sheriff Principal of Edinburgh, and was buried in Holyrood Abbey 14 November 1627.[14] Marie would not have been known as "Marie Lauder" after her marriage, because women in early modern Scotland did not usually adopt their husband's surnames.[15][16]

Hatton or Haltoun is an estate near Kirkliston in Ratho parish.[8] Alexander Lauder was a son of William Lauder (died 1596) and Jean Cockburn (died 1600). William Lauder hosted the Earl of Bothwell at Hatton on 23 April 1567, the day before he abducted Mary, Queen of Scots.[17][18] The poet Alexander Scott, who wrote Ane New Yeir Gift to Quene Mary was a connection by marriage of the Lauders.[19] Jean Cockburn's aunt, Elizabeth Douglas, Lady Temple Hall, was a poet, working in the same circle of East Lothian poets.[20]

Alexander Lauder with his younger brother got into trouble in 1596. They threatened Alexander McGill, the Provost of Corstorphine "under colour of friendship" because they wanted him to sign a contract.[21]

Marie Maitland, Lady Haltoun's children included:

- Alexander Lauder younger of Hatton (died 1623),[22] who married Susannah Cunningham, a daughter of the Earl of Glencairn, and sister of the writer Margaret Cunningham.

- Richard Lauder of Hatton (1589-1675), his younger daughter Elizabeth married Charles Maitland, later Earl of Lauderdale.[23]

- Jane Lauder, who married (1) Alexander Hay of Smithfield, (2) Bryce Sempill of Boghauche and Cathcart.[24]

- Helen Lauder (died 1620), who married Thomas Young of Leny, a lawyer.[25]

Marie Maitland died in June 1596. Soon after Marie's death, Alexander Lauder married Annabella Bellenden, a sister of the lawyer, Lewis or Ludovick Bellenden of Auchnoule, and sister-in-law of the courtier Margaret Livingstone, Countess of Orkney. Annabella would be a stepmother for their young children.[26]

George Lauder, a son of Alexander Lauder and Annabella Bellenden, was a soldier.[27][1] He was a friend of William Drummond of Hawthornden and gained a considerable reputation as a poet.[28]

Further reading

[edit]- King, Pamela E., "Lethington, Marie Maitland and the 'Maitland Quarto': Memorialisation and Performance in Times of 'Troubill' for Scotland", in Brown, Ian & Goodard Desmarest, Clarisse (eds.) (2023), Writing Scottishness: Literature and the Shaping of Scottish National Identities, Association for Scottish Literature Occasional Papers Number 26, Glasgow, pp. 20 - 43, ISBN 978-1-908980-39-7

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Crockett, William Shillinglaw (1893). Minstrelsy of the Merse: The Poets and Poetry of Berwickshire : a Country Anthology. J. and R. Parlane. p. 35.

- ^ Lethington, Richard Maitland of (2012-02-12), English: Two pages from the Maitland Quarto Manuscript of Scots literature. Sixteenth Century. Held by the Pepys Library in Cambridge., retrieved 2019-09-23

- ^ Andrea Thomas, Glory and Honour: The Renaissance in Scotland (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2013), pp. 154, 173.

- ^ National Library of Scotland: Wee Windaes Poem 49

- ^ a b "Maitland, Mary (d. 1596), writer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68146. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Henderson, Thomas Finlayson. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. pp. 368–370.

- ^ a b Loughlin, Mark (2008). "Maitland, William, of Lethington". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17838.

- ^ a b Joanna M. Martin, The Maitland Quarto (Scottish Text Society, 2015), pp. 28-32.

- ^ Jane Stevenson & Peter Davidson, Early Modern Women Poets (1520-1700), An Anthology (Oxford, 2001), p. 98: Bob Harris & Alan R. MacDonald, Scotland: Making and Unmaking of the Nation (Dundee, 2006), p. 289.

- ^ King, Pamela M., "Lethington, Marie Maitland, and the 'Maitland Quarto': Memorialisation and Performance in Times of 'Troubill' for Scotland", in Brown, Ian & Godard Desmarest, Clarisse (eds.) (2023), Writing Scottishness: Writing and the Shaping of National Identities, Association for Scottish Literature Occasional Papers Number 26, Glasgow, pp. 20 - 43, ISBN 978-1-908980-39-7

- ^ Martin, Joanna, "The Presentation of the Family in Maitland Writings", in Hadley-Williams, Janet & McClure, J. Derrick (eds.), Fresche Fontanis: Studies in the Culture of Medieval and Early Modern Scotland, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, pp. 318 - 330, ISBN 978-1-4438-4481-9

- ^ Marie Maitland: Scotland's 16th century Sappho, SNPG

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St Giles, The Bass: and the other homes of Dick-Lauder family (Edinburgh: Constable, 1898), p. 239.

- ^ Lorna Hutson, England's Insular Imagining: The Elizabethan Erasure of Scotland (Cambridge, 2023), p. 143.

- ^ Jenny Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community (London, 1981), p. 30.

- ^ History Workshop, What's in a Surname? Rebecca Mason

- ^ Robert Chambers, 'Locality of the Abduction of Queen Mary', PSAS, 2 (1859), p. 335

- ^ James Anderson, Collections relating to the History of Mary Queen of Scots, 2, p. 275.

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St. Giles (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 239-40: Register of the Privy Council', 1578-1585 (Edinburgh, 1880), pp. 237, 635, 637.

- ^ Sebastiaan Verweij, The Literary Culture of Early Modern Scotland (Oxford, 2017), pp. 81, 84-87.

- ^ Winifred Coutts, The Business of the College of Justice in 1600 (Edinburgh: Stair Society, 2003), pp. 561-2, NRS CS7/187/346v.

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St Giles, The Bass: and the other homes of Dick-Lauder family (Edinburgh: Constable, 1898), p. 242.

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St. Giles (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 245.

- ^ Adrian Cox, 'Decorative Plaster', Brian Kerr, 'Cathcart Castle, Glasgow: Excavations 1980–81', Scottish Archaeological Journal, 38 (2016), pp. 61-66.

- ^ Helen Lauder's will details her costume and jewellery, National Records of Scotland CC8/8/51 pp. 151-2.

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St. Giles (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 241.

- ^ Bayne, T.W. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 32. p. 195.

- ^ Jane Stewart Smith, The Grange of St. Giles (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 243-5.