Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these military expeditions are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that had the objective of reconquering Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Muslim rule. Beginning with the First Crusade, which resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, dozens of military campaigns were organised, providing a focal point of European history for centuries. Crusading declined rapidly after the 15th century.

In 1095, after a Byzantine request for aid,[1] Pope Urban II proclaimed the first expedition at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos and called for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in Western Europe, there was an enthusiastic response. Participants came from all over Europe and had a variety of motivations. These included religious salvation, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic or political advantage. Later expeditions were conducted by generally more organised armies, sometimes led by a king. All were granted papal indulgences. Initial successes established four Crusader states: the County of Edessa; the Principality of Antioch; the Kingdom of Jerusalem; and the County of Tripoli. A European presence remained in the region in some form until the fall of Acre in 1291. After this, no further large military campaigns were organised.

Other church-sanctioned campaigns include crusades against Christians not obeying papal rulings and heretics, those against the Ottoman Empire, and ones for political reasons. The struggle against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula–the Reconquista–ended in 1492 with the Fall of Granada. From 1147, the Northern Crusades were fought against pagan tribes in Northern Europe. Crusades against Christians began with the Albigensian Crusade in the 13th century and continued through the Hussite Wars in the early 15th century. Crusades against the Ottomans began in the late 14th century and include the Crusade of Varna. Popular crusades, including the Children's Crusade of 1212, were generated by the masses and were unsanctioned by the Church.

Terminology

The term "crusade" first referred to military expeditions undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries to the Holy Land. The conflicts to which the term is applied has been extended to include other campaigns initiated, supported and sometimes directed by the Latin Church with varying objectives, mostly religious, sometimes political. These differed from previous Christian religious wars in that they were considered a penitential exercise, and so earned participants remittance from penalties for all confessed sins.[2] What constituted a crusade has been understood in diverse ways, particularly regarding the early Crusades, and the precise definition remains a matter of debate among contemporary historians.[3][4]

At the time of the First Crusade, iter, "journey", and peregrinatio, "pilgrimage" were used for the campaign. Crusader terminology remained largely indistinguishable from that of Christian pilgrimage during the 12th century. A specific term for a crusader in the form of crucesignatus—"one signed by the cross"—emerged in the early 12th century. This led to the French term croisade—the way of the cross.[3] By the mid 13th century the cross became the major descriptor of the crusades with crux transmarina—"the cross overseas"—used for crusades in the eastern Mediterranean, and crux cismarina—"the cross this side of the sea"—for those in Europe.[5] The use of croiserie, "crusade" in Middle English can be dated to c. 1300, but the modern English "crusade" dates to the early 1700s.[6] The Crusader states of Syria and Palestine were known as the "Outremer" from the French outre-mer, or "the land beyond the sea".[7]

Crusades and the Holy Land, 1095–1291

Background

By the end of the 11th century, the period of Islamic Arab territorial expansion had been over for centuries. The Holy Land's remoteness from focus of Islamic power struggles enabled relative peace and prosperity in Syria and Palestine. Muslim-Western European contact was only more than minimal in the conflict in the Iberian Peninsula.[8] The Byzantine Empire and the Islamic world were long standing centres of wealth, culture and military power. The Arab-Islamic world tended to view Western Europe as a backwater that presented little organised threat.[9] By 1025, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II had extended territorial recovery to its furthest extent. The frontiers stretched east to Iran. Bulgaria and much of southern Italy were under control, and piracy was suppressed in the Mediterranean Sea. The empire's relationships with its Islamic neighbours were no more quarrelsome than its relationships with the Slavs or the Western Christians. The Normans in Italy; to the north Pechenegs, Serbs and Cumans; and Seljuk Turks in the east all competed with the Empire and the emperors recruited mercenaries—even on occasions from their enemies—to meet this challenge.[10]

The political situation in Western Asia was changed by later waves of Turkic migration, in particular the arrival of the Seljuk Turks in the 10th century. Previously a minor ruling clan from Transoxania, they had recently converted to Islam and migrated into Iran. In two decades following their arrival they conquered Iran, Iraq and the Near East. The Seljuks and their followers were from the Sunni tradition. This brought them into conflict in Palestine and Syria with the Fatimids who were Shi'ite.[11] The Seljuks were nomadic, Turkic speaking and occasionally shamanistic, very different from their sedentary, Arabic speaking subjects. This difference and the governance of territory based on political preference, and competition between independent princes rather than geography, weakened existing power structures.[12] In 1071, Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes attempted confrontation to suppress the Seljuks' sporadic raiding, leading to his defeat at the battle of Manzikert. Historians once considered this a pivotal event but now Manzikert is regarded as only one further step in the expansion of the Great Seljuk Empire.[13]

The evolution of a Christian theology of war developed from the link of Roman citizenship to Christianity, according to which citizens were required to fight the empire's enemies. This doctrine of holy war dated from the 4th-century theologian Saint Augustine. He maintained that aggressive war was sinful, but acknowledged a "just war" could be rationalised if it was proclaimed by a legitimate authority, was defensive or for the recovery of lands, and without an excessive degree of violence.[14][15] Violent acts were commonly used for dispute resolution in Western Europe, and the papacy attempted to mitigate this.[16] Historians have thought that the Peace and Truce of God movements restricted conflict between Christians from the 10th century; the influence is apparent in Urban II's speeches. Other historians assert that the effectiveness was limited and it had died out by the time of the crusades.[17] Pope Alexander II developed a system of recruitment via oaths for military resourcing that his successor Pope Gregory VII extended across Europe.[18] In the 11th century, Christian conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom was sponsored by the Church, including the siege of Barbastro and the Norman conquest of Sicily.[19] In 1074, Gregory VII planned a display of military power to reinforce the principle of papal sovereignty. His vision of a holy war supporting Byzantium against the Seljuks was the first crusade prototype, but lacked support.[20]

The First Crusade was an unexpected event for contemporary chroniclers, but historical analysis demonstrates it had its roots in earlier developments with both clerics and laity recognising Jerusalem's role in Christianity as worthy of penitential pilgrimage. In 1071, Jerusalem was captured by the Turkish warlord Atsiz, who seized most of Syria and Palestine as part of the expansion of the Seljuks throughout the Middle East. The Seljuk hold on the city was weak and returning pilgrims reported difficulties and the oppression of Christians. Byzantine desire for military aid converged with increasing willingness of the western nobility to accept papal military direction.[21][22]

First Crusade

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested military aid from Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza. He was probably expecting a small number of mercenaries he could direct. Alexios had restored the Empire's finances and authority but still faced numerous foreign enemies. Later that year at the Council of Clermont, Urban raised the issue again and preached a crusade.[23] Almost immediately, the French priest Peter the Hermit gathered thousands of mostly poor in the People's Crusade.[24] Traveling through Germany, German bands massacred Jewish communities in the Rhineland massacres during wide-ranging anti-Jewish activities.[25] Jews were perceived to be as much an enemy as Muslims. They were held responsible for the Crucifixion, and were more immediately visible. People wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were many closer to home.[26] Quickly after leaving Byzantine-controlled territory on their journey to Nicaea, these crusaders were annihilated in a Turkish ambush at the Battle of Civetot.[27]

Conflict with Urban II meant that King Philip I of France and Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV declined to participate. Aristocrats from France, western Germany, the Low Countries, Languedoc and Italy led independent contingents in loose, fluid arrangements based on bonds of lordship, family, ethnicity and language. The elder statesman Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse was foremost, rivaled by the relatively poor but martial Italo-Norman Bohemond of Taranto and his nephew Tancred. Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin also joined with forces from Lorraine, Lotharingia, and Germany. These five princes were pivotal to the campaign, which was augmented by a northern French army led by Robert Curthose, Count Stephen II of Blois, and Count Robert II of Flanders.[28] The total number may have reached as many as 100,000 people including non-combatants. They traveled eastward by land to Constantinople where they were cautiously welcomed by the emperor.[29] Alexios persuaded many of the princes to pledge allegiance to him and that their first objective should be Nicaea, the capital of the Sultanate of Rum. Sultan Kilij Arslan left the city to resolve a territorial dispute, enabling its capture after the siege of Nicaea and a Byzantine naval assault in the high point of Latin and Greek co-operation.[30]

The first experience of Turkish tactics, using lightly armoured mounted archers, occurred when an advanced party led by Bohemond and Robert was ambushed at the battle of Dorylaeum. The Normans resisted for hours before the arrival of the main army caused a Turkish withdrawal.[31] The army marched for three months to the former Byzantine city Antioch, that had been in Muslim control since 1084. Starvation, thirst and disease reduced numbers, combined with Baldwin's decision to leave with 100 knights and their followers to carve out his own territory in Edessa.[32] The siege of Antioch lasted eight months. The crusaders lacked the resources to fully invest the city; the residents lacked the means to repel the invaders. Then Bohemond persuaded a guard in the city to open a gate. The crusaders entered, massacring the Muslim inhabitants and many Christians amongst the Greek Orthodox, Syrian and Armenian communities.[33] A force to recapture the city was raised by Kerbogha, the effective ruler of Mosul. The Byzantines did not march to the assistance of the crusaders after the deserting Stephen of Blois told them the cause was lost. Alexius retreated from Philomelium, where he received Stephen's report, to Constantinople. The Greeks were never truly forgiven for this perceived betrayal and Stephen was branded a coward.[34] Losing numbers through desertion and starvation in the besieged city, the crusaders attempted to negotiate surrender but were rejected. Bohemond recognised that the only option was open combat and launched a counterattack. Despite superior numbers, Kerbogha's army—which was divided into factions and surprised by the Crusaders commitment—retreated and abandoned the siege.[35] Raymond besieged Arqa in February 1099 and sent an embassy to al-Afdal Shahanshah, the vizier of Fatimid Egypt, seeking a treaty. The Pope's representative Adhemar died, leaving the crusade without a spiritual leader. Raymond failed to capture Arqa and in May led the remaining army south along the coast. Bohemond retained Antioch and remained, despite his pledge to return it to the Byzantines. Local rulers offered little resistance, opting for peace in return for provisions. The Frankish envoys returned accompanied by Fatimid representatives. This brought the information that the Fatimids had recaptured Jerusalem. The Franks offered to partition conquered territory in return for the city. Refusal of the offer made it imperative that the crusade reach Jerusalem before the Fatimids made it defensible.[36]

The first attack on the city, launched on 7 June 1099, failed, and the siege of Jerusalem became a stalemate, before the arrival of craftsmen and supplies transported by the Genoese to Jaffa tilted the balance. Two large siege engines were constructed and the one commanded by Godfrey breached the walls on 15 July. For two days the crusaders massacred the inhabitants and pillaged the city. Historians now believe the accounts of the numbers killed have been exaggerated, but this narrative of massacre did much to cement the crusaders' reputation for barbarism.[37] Godfrey secured the Frankish position by defeating an Egyptian force at the Battle of Ascalon on 12 August.[38] Most of the crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe. When it came to the future governance of the city it was Godfrey who took leadership and the title of Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri, Defender of the Holy Sepulchre. The presence of troops from Lorraine ended the possibility that Jerusalem would be an ecclesiastical domain and the claims of Raymond.[39] Godfrey was left with a mere 300 knights and 2,000 infantry. Tancred also remained with the ambition to gain a princedom of his own.[40]

The Islamic world seems to have barely registered the crusade; certainly, there is limited written evidence before 1130. This may be in part due to a reluctance to relate Muslim failure, but it is more likely to be the result of cultural misunderstanding. Al-Afdal Shahanshah and the Muslim world mistook the crusaders for the latest in a long line of Byzantine mercenaries, not religiously motivated warriors intent on conquest and settlement.[41] The Muslim world was divided between the Sunnis of Syria and Iraq and the Shi'ite Fatimids of Egypt. The Turks had found unity unachievable since the death of Sultan Malik-Shah in 1092, with rival rulers in Damascus and Aleppo.[42] In addition, in Baghdad, Seljuk sultan Barkiyaruq and Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir were engaged in a power struggle. This gave the Crusaders a crucial opportunity to consolidate without any pan-Islamic counter-attack.[43]

Early 12th century

Urban II died on 29 July 1099, fourteen days after the capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, but before news of the event had reached Rome. He was succeeded by Pope Paschal II who continued the policies of his predecessors in regard to the Holy Land.[44] Godfrey died in 1100. Dagobert of Pisa, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem and Tancred looked to Bohemond to come south, but he was captured by the Danishmends.[45] The Lorrainers foiled the attempt to seize power and enabled Godfrey's brother, Baldwin I, to take the crown.[46]

Paschal II promoted the large-scale Crusade of 1101 in support of the remaining Franks. This new crusade was a similar size to the First Crusade and joined in Byzantium by Raymond of Saint-Gilles. Command was fragmented and the force split in three:[44]

- A largely Lombard force was harried by Kilij Arslan's forces and finally destroyed in three days at the battle of Mersivan in August 1101. Some of the leadership, including Raymond, Stephen of Blois and Anselm IV of Milan, survived to retreat to Constantinople.

- A force led by William II of Nevers attempted catch up with the Lombards but was caught and routed at Heraclea. The destitute leaders eventually reached Antioch.

- William IX of Aquitaine, Welf IV of Bavaria, Ida of Formbach-Ratelnberg and Hugh, Count of Vermandois reached Heraclea later and were also defeated. Again the leaders fled the field and survived, although Hugh died of his wounds at Tarsus and Ida disappeared. The remnants of the army helped Raymond capture Tortosa.[47]

The defeat of the crusaders proved to the Muslim world that the crusaders were not invincible, as they appeared to be during the First Crusade. Within months of the defeat, the Franks and Fatimid Egypt began fighting in three battles at Ramla, and one at Jaffa:

- In the first on 7 September 1101, Baldwin I and 300 knights narrowly defeated the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah.[48]

- In the second on 17 May 1102, al-Afdal's son Sharaf al-Ma'ali and a superior force inflicted a major defeat on the Franks. Stephen of Blois and Stephen of Burgundy from the Crusade of 1101 were among those killed. Baldwin I fled to Arsuf.[48]

- Victory at the battle of Jaffa on 27 May 1102 saved the kingdom from virtual collapse.[48]

- In the third at Ramla on 28 August 1102, a coalition of Fatimid and Damescene forces were defeated again by Baldwin I and 500 knights.[49]

Baldwin of Edessa, later king of Jerusalem as Baldwin II, and Patriarch Bernard of Valence ransomed Bohemond for 100,000 gold pieces.[50] Baldwin and Bohemond then jointly campaigned to secure Edessa's southern front. On 7 May 1104, the Frankish army was defeated by the Seljuk rulers of Mosul and Mardin at the battle of Harran.[49] Baldwin II and his cousin, Joscelin of Courtenay, were captured. Bohemond and Tancred retreated to Edessa where Tancred assumed command. Bohemond returned to Italy, taking with him much of Antioch's wealth and manpower. Tancred revitalised the beleaguered principality with victory at the battle of Artah on 20 April 1105 over a larger force, led by the Seljuk Ridwan of Aleppo. He was then able to secure Antioch's borders and push back his Greek and Muslim enemies.[51] Under Paschal's sponsorship, Bohemond launched a version of a crusade in 1107 against the Byzantines, crossing the Adriatic and besieging Durrës. The siege failed; Alexius hit his supply lines, forcing his surrender. The terms laid out in the Treaty of Devol were never enacted because Bohemond remained in Apulia and died in 1111, leaving Tancred as notional regent for his son Bohemond II.[52] In 1007, the people of Tell Bashir ransomed Joscelin and he negotiated Baldwin's release from Jawali Saqawa, atabeg of Mosul, in return for money, hostages and military support. Tancred and Baldwin, supported by their respective Muslim allies, entered violent conflict over the return of Edessa leaving 2,000 Franks dead before Bernard of Valence, patriarch of both Antioch and Edessa, adjudicated in Baldwin's favour.[53]

On 13 May 1110, Baldwin II and a Genoese fleet captured Beirut.[54][55] In the same month, Muhammad I Tapar, sultan of the Seljuk Empire, sent an army to recover Syria, but a Frankish defensive force arrived at Edessa, ending the short siege of the city.[56] On 4 December, Baldwin captured Sidon, aided by a flotilla of Norwegian pilgrims led by Sigurd the Crusader.[54][55] Next year, Tancred's extortion from Antioch's Muslim neighbours provoked the inconclusive battle of Shaizar between the Franks and an Abbasid army led by the governor of Mosul, Mawdud. Tancred died in 1112 and power passed to his nephew Roger of Salerno.[57] In May 1113, Mawdud invaded Galilee with Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus. On 28 June this force surprised Baldwin, chasing the Franks from the field at the battle of al-Sannabra. Mawdud was killed by Assassins. Bursuq ibn Bursuq led the Seljuk army in 1115 against an alliance of the Franks, Toghtekin, his son-in-law Ilghazi and the Muslims of Aleppo. Bursuq feigned retreat and the coalition disbanded. Only the forces of Roger and Baldwin of Edessa remained, but, heavily outnumbered, they were victorious on 14 September at the first battle of Tell Danith.[58]

In April 1118, Baldwin I died of illness while raiding in Egypt.[59] His cousin, Baldwin of Edessa, was unanimously elected his successor. [60] In June 1119, Ilghazi, now emir of Aleppo, attacked Antioch with more than 10,000 men. Roger of Salerno's army of 700 knights, 3,000 foot soldiers and a corps of Turcopoles was defeated at the battle of Ager Sanguinis, or field of blood, and Roger was among the many killed.[61] Baldwin II's counter-attack forced the offensive's end, after an inconclusive second battle of Tell Danith.[61]

In January 1120 the secular and ecclesiastical leaders of the Outremer gathered at the Council of Nablus. The council laid a foundation of a law code for the kingdom of Jerusalem that replaced common law.[62] The council also heard the first direct appeals for support made to the Papacy and Republic of Venice. They responded with the Venetian Crusade, sending a large fleet that supported the capture of Tyre in 1124.[63] In April 1123, Baldwin II was ambushed and captured by Belek Ghazi while campaigning north of Edessa, along with Joscelin I, Count of Edessa. He was released in August 1024 in return for 80,000 gold pieces and the city of Azaz.[64] In 1129, the Council of Troyes approved the rule of the Knights Templar for Hugues de Payens. He returned to the East with a major force including Fulk V of Anjou. This allowed the Franks to capture the town of Banias during the Crusade of 1129. Defeat at Damascus and Marj al-Saffar ended the campaign and Frankish influence on Damascus for years.[65]

The Levantine Franks sought alliances with the Latin West through the marriage of heiresses to wealthy martial aristocrats. Constance of Antioch was married to Raymond of Poitiers, son of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine. Baldwin II's eldest daughter Melisende of Jerusalem was married to Fulk of Anjou in 1129. When Baldwin II died on 21 August 1131. Fulk and Melisende were consecrated joint rulers of Jerusalem. Despite conflict caused by the new king appointing his own supporters and the Jerusalemite nobles attempting to curb his rule, the couple were reconciled and Melisende exercised significant influence. When Fulk died in 1143, she became joint ruler with their son, Baldwin III of Jerusalem.[66] At the same time, the advent of Imad ad-Din Zengi saw the Crusaders threatened by a Muslim ruler who would introduce jihad to the conflict, joining the powerful Syrian emirates in a combined effort against the Franks.[67] He became atabeg of Mosul in September 1127 and used this to expand his control to Aleppo in June 1128.[68] In 1135, Zengi moved against Antioch and, when the Crusaders failed to put an army into the field to oppose him, he captured several important Syrian towns. He defeated Fulk at the battle of Ba'rin of 1137, seizing Ba'rin Castle.[69]

In 1137, Zengi invaded Tripoli, killing the count Pons of Tripoli.[70] Fulk intervened, but Zengi's troops captured Pons' successor Raymond II of Tripoli, and besieged Fulk in the border castle of Montferrand. Fulk surrendered the castle and paid Zengi a ransom for his and Raymond's freedom. John II Komnenos, emperor since 1118, reasserted Byzantine claims to Cilicia and Antioch, compelling Raymond of Poitiers to give homage. In April 1138, the Byzantines and Franks jointly besieged Aleppo and, with no success, began the Siege of Shaizar, abandoning it a month later.[71]

On 13 November 1143, while the royal couple were in Acre, Fulk was killed in a hunting accident. On Christmas Day 1143, their son Baldwin III of Jerusalem was crowned co-ruler with his mother.[72] That same year, having prepared his army for a renewed attack on Antioch, John II Komnenos cut himself with a poisoned arrow while hunting wild boar. He died on 8 April 1143 and was succeeded as emperor by his son Manuel I Komnenos.[73]

Following John's death, the Byzantine army withdrew, leaving Zengi unopposed. Fulk's death later in the year left Joscelin II of Edessa with no powerful allies to help defend Edessa. Zengi came north to begin the first siege of Edessa, arriving on 28 November 1144.[74] The city had been warned of his arrival and was prepared for a siege, but there was little they could do. Zengi realised there was no defending force and surrounded the city. The walls collapsed on 24 December 1144. Zengi's troops rushed into the city, killing all those who were unable to flee. All the Frankish prisoners were executed, but the native Christians were allowed to live. The Crusaders were dealt their first major defeat.[75]

Zengi was assassinated by a slave on 14 September 1146 and was succeeded in the Zengid dynasty by his son Nūr-ad-Din. The Franks recaptured the city during the Second Siege of Edessa of 1146 by stealth but could not take or even properly besiege the citadel.[76] After a brief counter-siege, Nūr-ad-Din took the city. The men were massacred, with the women and children enslaved, and the walls razed.[77]

Second Crusade

The fall of Edessa caused great consternation in Jerusalem and Western Europe, tempering the enthusiastic success of the First Crusade. Calls for a new crusade – the Second Crusade – were immediate, and was the first to be led by European kings. Concurrent campaigns as part of the Reconquista and Northern Crusades are also sometimes associated with this Crusade.[78] The aftermath of the Crusade saw the Muslim world united around Saladin, leading to the fall of Jerusalem.[79]

Eugene III, recently elected pope, issued the bull Quantum praedecessores in December 1145 calling for a new crusade, one that would be more organized and centrally controlled than the First. The armies would be led by the strongest kings of Europe and a route that would be pre-planned. The pope called on Bernard of Clairvaux to preach the Second Crusade, granting the same indulgences which had accorded to the First Crusaders. Among those answering the call were two European kings, Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. Louis, his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and many princes and lords prostrated themselves at the feet of Bernard in order to take the cross. Conrad and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa also received the cross from the hand of Bernard.[80]

Conrad III and the German contingent planned to leave for the Holy Land at Easter, but did not depart until May 1147. When the German army began to cross Byzantine territory, emperor Manuel I had his troops posted to ensure against trouble. A brief Battle of Constantinople in September ensued, and their defeat at the emperor's hand convinced the Germans to move quickly to Asia Minor. Without waiting for the French contingent, Conrad III engaged the Seljuks of Rûm under sultan Mesud I, son and successor of Kilij Arslan, the nemesis of the First Crusade. Mesud and his forces almost totally destroyed Conrad's contingent at the Second Battle of Dorylaeum on 25 October 1147.[81]

The French contingent departed in June 1147. In the meantime, Roger II of Sicily, an enemy of Conrad's, had invaded Byzantine territory. Manuel I needed all his army to counter this force, and, unlike the armies of the First Crusade, the Germans and French entered Asia with no Byzantine assistance. The French met the remnants of Conrad's army in northern Turkey, and Conrad joined Louis's force. They fended off a Seljuk attack at the Battle of Ephesus on 24 December 1147. A few days later, they were again victorious at the Battle of the Meander. Louis was not as lucky at the Battle of Mount Cadmus on 6 January 1148 when the army of Mesud inflicted heavy losses on the Crusaders. Shortly thereafter, they sailed for Antioch, almost totally destroyed by battle and sickness.[82]

The Crusader army arrived at Antioch on 19 March 1148 with the intent on moving to retake Edessa, but Baldwin III of Jerusalem and the Knights Templar had other ideas. The Council of Acre was held on 24 June 1148, changing the objective of the Second Crusade to Damascus, a former ally of the kingdom that had shifted its allegiance to that of the Zengids. The Crusaders fought the Battle of Bosra with the Damascenes in the summer of 1147, with no clear winner.[83] Bad luck and poor tactics of the Crusaders led to the disastrous five-day siege of Damascus from 24 to 28 July 1148.[84] The barons of Jerusalem withdrew support and the Crusaders retreated before the arrival of a relief army led by Nūr-ad-Din. Morale fell, hostility to the Byzantines grew and distrust developed between the newly arrived Crusaders and those that had made the region their home after the earlier crusades. The French and German forces felt betrayed by the other, lingering for a generation due to the defeat, to the ruin of the Christian kingdoms in the Holy Land.[85]

In the spring of 1147, Eugene III authorised the expansion of his mission into the Iberian Peninsula, equating these campaigns against the Moors with the rest of the Second Crusade. The successful Siege of Lisbon, from 1 July to 25 October 1147, was followed by the six-month siege of Tortosa, ending on 30 December 1148 with a defeat for the Moors.[86] In the north, some Germans were reluctant to fight in the Holy Land while the pagan Wends were a more immediate problem. The resulting Wendish Crusade of 1147 was partially successful but failed to convert the pagans to Christianity.[87]

The disastrous performance of this campaign in the Holy Land damaged the standing of the papacy, soured relations between the Christians of the kingdom and the West for many years, and encouraged the Muslims of Syria to even greater efforts to defeat the Franks. The dismal failures of this Crusade then set the stage for the fall of Jerusalem, leading to the Third Crusade.[85]

Nūr-ad-Din and the rise of Saladin

In the first major encounter after the Second Crusade, Nūr-ad-Din's forces then destroyed the Crusader army at the Battle of Inab on 29 June 1149. Raymond of Poitiers, as prince of Antioch, came to the aid of the besieged city. Raymond was killed and his head was presented to Nūr-ad-Din, who forwarded it to the caliph al-Muqtafi in Baghdad.[88] In 1150, Nūr-ad-Din defeated Joscelin II of Edessa for a final time, resulting in Joscelin being publicly blinded, dying in prison in Aleppo in 1159. Later that year, at the Battle of Aintab, he tried but failed to prevent Baldwin III's evacuation of the residents of Turbessel.[89] The unconquered portions of the County of Edessa would nevertheless fall to the Zengids within a few years. In 1152, Raymond II of Tripoli became the first Frankish victim of the Assassins.[90] Later that year, Nūr-ad-Din captured and burned Tortosa, briefly occupying the town before it was taken by the Knights Templar as a military headquarters.[91]

After the Siege of Ascalon ended on 22 August 1153 with a Crusader victory, Damascus was taken by Nūr-ad-Din the next year, uniting all of Syria under Zengid rule. In 1156, Baldwin III was forced into a treaty with Nūr-ad-Din, and later entered into an alliance with the Byzantine Empire. On 18 May 1157, Nūr-ad-Din began a siege on the Knights Hospitaller contingent at Banias, with the Grand Master Bertrand de Blanquefort captured. Baldwin III was able to break the siege, only to be ambushed at Jacob's Ford in June. Reinforcements from Antioch and Tripoli were able to relieve the besieged Crusaders, but they were defeated again that month at the Battle of Lake Huleh. In July 1158, the Crusaders were victorious at the Battle of Butaiha. Bertrand's captivity lasted until 1159, when emperor Manuel I negotiated an alliance with Nūr-ad-Din against the Seljuks.[92]

Baldwin III died on 10 February 1163, and Amalric of Jerusalem was crowned as king of Jerusalem eight days later.[93] Later that year, he defeated the Zengids at the Battle of al-Buqaia. Amalric then undertook a series of four invasions of Egypt from 1163 to 1169, taking advantage of weaknesses of the Fatimids.[73] Nūr-ad-Din's intervention in the first invasion allowed his general Shirkuh, accompanied by his nephew Saladin, to enter Egypt.[94] Shawar, the deposed vizier to the Fatimid caliph al-Adid, allied with Amalric I, attacking Shirkuh at the second Siege of Bilbeis beginning in August 1164, following Amalric's unsuccessful first siege in September 1163.[95] This action left the Holy Land lacking in defenses, and Nūr-ad-Din defeated a Crusader forces at the Battle of Harim in August 1164, capturing most of the Franks' leaders.[96]

After the sacking of Bilbeis, the Crusader-Fatimid force was to meet Shirkuh's army in the indecisive Battle of al-Babein on 18 March 1167. In 1169, both Shawar and Shirkuh died, and al-Adid appointed Saladin as vizier. Saladin, with reinforcements from Nūr-ad-Din, defeated a massive Crusader-Byzantine force at the Siege of Damietta in late October.[97] This gained Saladin the attention of the Assassins, with attempts on his life in January 1175 and again on 22 May 1176.[98]

Baldwin IV of Jerusalem[99] became king on 5 July 1174 at the age of 13.[100] As a leper he was not expected to live long, and served with a number of regents, and served as co-ruler with his cousin Baldwin V of Jerusalem beginning in 1183. Baldwin IV, Raynald of Châtillon and the Knights Templar defeated Saladin at the celebrated Battle of Montgisard on 25 November 1177. In June 1179, the Crusaders were defeated at the Battle of Marj Ayyub, and in August the unfinished castle at Jacob's Ford fell to Saladin, with the slaughter of half its Templar garrison. However, the kingdom repelled his attacks at the Battle of Belvoir Castle in 1182 and later in the Siege of Kerak of 1183.[101]

Fall of Jerusalem

Baldwin V became sole king upon the death of his uncle in 1185 under the regency of Raymond III of Tripoli. Raymond negotiated a truce with Saladin which went awry when the king died in the summer of 1186.[102] His mother Sibylla of Jerusalem and her husband Guy of Lusignan were crowned as queen and king of Jerusalem in the summer of 1186, shortly thereafter. They immediately had to deal with the threat posed by Saladin.[103]

Despite his defeat at the Battle of al-Fule in the fall of 1183, Saladin increased his attacks against the Franks, leading to their defeat at the Battle of Cresson on 1 May 1187. Guy of Lusignan responded by raising the largest army that Jerusalem had ever put into the field. Saladin lured this force into inhospitable terrain without water supplies and routed them at the Battle of Hattin on 4 July 1187. One of the major commanders was Raymond III of Tripoli who saw his force slaughtered, with some knights deserting to the enemy, and narrowly escaping, only to be regarded as a traitor and coward.[104] Guy of Lusignan was one of the few captives of Saladin's after the battle, along with Raynald of Châtillon and Humphrey IV of Toron. Raynald was beheaded, settling an old score. Guy and Humphrey were imprisoned in Damascus and later released in 1188.[105]

As a result of his victory, much of Palestine quickly fell to Saladin. The siege of Jerusalem began on 20 September 1187 and the Holy City was surrendered to Saladin by Balian of Ibelin on 2 October. According to some, on 19 October 1187, Urban III died upon of hearing of the defeat.[106] Jerusalem was once again in Muslim hands. Many in the kingdom fled to Tyre, and Saladin's subsequent attack at the siege of Tyre beginning in November 1187 was unsuccessful. The siege of Belvoir Castle began the next month and the Hospitaller stronghold finally fell a year later. The sieges of Laodicea and Sahyun Castle in July 1188 and the sieges of al-Shughur and Bourzey Castle in August 1188 further solidified Saladin's gains. The siege of Safed in late 1188 then completed Saladin's conquest of the Holy Land.[100]

Third Crusade

The years following the founding of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were met with multiple disasters. The Second Crusade did not achieve its goals, and left the Muslim East in a stronger position with the rise of Saladin. A united Egypt–Syria led to the loss of Jerusalem itself, and Western Europe had no choice but to launch the Third Crusade, this time led by the kings of Europe.[107]

The news of the disastrous defeat at the battle of Hattin and subsequent fall of Jerusalem gradually reached Western Europe. Urban III died shortly after hearing the news, and his successor Gregory VIII issued the bull Audita tremendi on 29 October 1187 describing the events in the East and urging all Christians to take up arms and go to the aid of those in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, calling for a new crusade to the Holy Land – the Third Crusade – to be led by Frederick Barbarossa and Richard I of England.[108]

Frederick took the cross in March 1188.[109] Frederick sent an ultimatum to Saladin, demanding the return of Palestine and challenging him to battle and in May 1189, Frederick's host departed for Byzantium. In March 1190, Frederick embarked to Asia Minor. The armies coming from western Europe pushed on through Anatolia, defeating the Turks and reaching as far as Cilician Armenia. On 10 June 1190, Frederick drowned near Silifke Castle. His death caused several thousand German soldiers to leave the force and return home. The remaining German army moved under the command of the English and French forces that arrived shortly thereafter.[110]

Richard the Lionheart had already taken the cross as the Count of Poitou in 1187. His father Henry II of England and Philip II of France had done so on 21 January 1188 after receiving news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin.[111][112] Richard I and Philip II of France agreed to go on the Crusade in January 1188. Arriving in the Holy Land, Richard led his support to the stalemated siege of Acre. The Muslim defenders surrendered on 12 July 1191. Richard remained in sole command of the Crusader force after the departure of Philip II on 31 July 1191. On 20 August 1191, Richard had more than 2000 prisoners beheaded at the massacre of Ayyadieh. Saladin subsequently ordered the execution of his Christian prisoners in retaliation.[113]

Richard moved south, defeating Saladin's forces at the battle of Arsuf on 7 September 1191. Three days later, Richard took Jaffa, held by Saladin since 1187, and advanced inland towards Jerusalem.[114] On 12 December 1191 Saladin disbanded the greater part of his army. Learning this, Richard pushed his army forward, to within 12 miles from Jerusalem before retreating back to the coast. The Crusaders made another advance on Jerusalem, coming within sight of the city in June before being forced to retreat again. Hugh III of Burgundy, leader of the Franks, was adamant that a direct attack on Jerusalem should be made. This split the Crusader army into two factions, and neither was strong enough to achieve its objective. Without a united command the army had little choice but to retreat back to the coast.

On 27 July 1192, Saladin's army began the battle of Jaffa, capturing the city. Richard's forces stormed Jaffa from the sea and the Muslims were driven from the city. Attempts to retake Jaffa failed and Saladin was forced to retreat.[115] On 2 September 1192 Richard and Saladin entered into the Treaty of Jaffa, providing that Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control, while allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and traders to freely visit the city. This treaty ended the Third Crusade.[116]

Crusade of 1197

Three years later, Henry VI launched the Crusade of 1197. While his forces were en route to the Holy Land, Henry VI died in Messina on 28 September 1197. The nobles that remained captured the Levant coast between Tyre and Tripoli before returning to Germany. The Crusade ended on 1 July 1198 after capturing Sidon and Beirut.[117]

Fourth Crusade

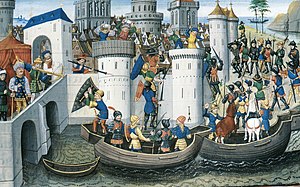

In 1198, the recently elected Pope Innocent III announced a new crusade, organised by three Frenchmen: Theobald of Champagne; Louis of Blois; and Baldwin of Flanders. After Theobald's premature death, the Italian Boniface of Montferrat replaced him as the new commander of the campaign. They contracted with the Republic of Venice for the transportation of 30,000 crusaders at a cost of 85,000 marks. However, many chose other embarkation ports and only around 15,000 arrived in Venice. The Doge of Venice Enrico Dandolo proposed that Venice would be compensated with the profits of future conquests beginning with the seizure of the Christian city of Zara. Pope Innocent III's role was ambivalent. He only condemned the attack when the siege started. He withdrew his legate to disassociate from the attack but seemed to have accepted it as inevitable. Historians question whether for him, the papal desire to salvage the crusade may have outweighed the moral consideration of shedding Christian blood.[118] The crusade was joined by King Philip of Swabia, who intended to use the Crusade to install his exiled brother-in-law, Alexios IV Angelos, as Emperor. This required the overthrow of Alexios III Angelos, the uncle of Alexios IV. Alexios IV offered the crusade 10,000 troops, 200,000 marks and the reunion of the Greek Church with Rome if they toppled his uncle Emperor Alexios III.[119] When the crusade entered Constantinople, Alexios III fled and was replaced by his nephew. The Greek resistance prompted Alexios IV to seek continued support from the crusade until he could fulfil his commitments. This ended with his murder in a violent anti-Latin revolt. The crusaders were without seaworthy ships, supplies or food. Their only escape route was through the city, taking by force what Alexios had promised and the new anti-westerner Byzantine ruler – Alexios V Doukas – denied them. The Sack of Constantinople involved three days of pillaging churches and killing much of the Greek Orthodox Christian populace. This sack was not unusual considering the violent military standards of the time, but contemporaries such as Innocent III and Ali ibn al-Athir saw it as an atrocity against centuries of classical and Christian civilisation.[120]

Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the sultan al-Adil, brother of Saladin. In 1213, Innocent III called for another Crusade at the Fourth Lateran Council, and in the papal bull Quia maior.[121] Innocent died in 1216 and was succeeded by Honorius III who immediately called on Andrew II of Hungary and Frederick II of Germany to lead a Crusade.[122] Frederick had taken the cross in 1215, but hung back, with his crown still in contention, and Honorius delayed the expedition.[123]

Andrew II left for Acre in August 1217, joining John of Brienne, king of Jerusalem. The initial plan of a two-prong attack in Syria and in Egypt was abandoned and instead the objective became limited operations in Syria. After accomplishing little, the ailing Andrew returned to Hungary early in 1218. As it became clear that Frederick II was not coming to the east, the remaining commanders began the planning to attack the Egyptian port of Damietta.[124]

The fortifications of Damietta included the Burj al-Silsilah – the chain tower – with massive chains that could stretch across the Nile. The siege of Damietta began in June 1218 with a successful assault on the tower. The loss of the tower was a great shock to the Ayyubids, and the sultan al-Adil died soon thereafter.[125] He was succeeded as sultan by his son al-Kamil. Further offensive action by the Crusaders would have to wait until the arrival of additional forces, including legate Pelagius with a contingent of Romans.[126] A group from England arrived shortly thereafter.[127]

By February 1219, the Crusaders now had Damietta surrounded, and al-Kamil opened negotiations with the Crusaders, asking for envoys to come to his camp. He offered to surrender the kingdom of Jerusalem, less the fortresses of al-Karak and Krak de Montréal, guarding the road to Egypt, in exchange for the evacuation of Egypt. John of Brienne and the other secular leaders were in favor of the offer, as the original objective of the Crusade was the recovery of Jerusalem. But Pelagius and the leaders of the Templars and Hospitallers refused.[128] Later, Francis of Assisi arrived to negotiate unsuccessfully with the sultan.[129]

In November 1219, the Crusaders entered Damietta and found it abandoned, al-Kamil having moved his army south. In the captured city, Pelagius was unable to prod the Crusaders from their inactivity, and many returned home, their vow fulfilled. Al-Kamil took advantage of this lull to reinforce his new camp at Mansurah, renewing his peace offering to the Crusaders, which was again refused. Frederick II sent troops and word that he would soon follow, but they were under orders not to begin offensive operations until he had arrived.[130]

In July 1221, Pelagius began to advance to the south. John of Brienne argued against the move, but was powerless to stop it. Already deemed a traitor for opposing the plans and threatened with excommunication, John joined the force under the command of the legate. In the ensuing Battle of Mansurah in late August, al-Kamil had the sluices along the right bank of the Nile opened, flooding the area and rendering battle impossible.[131] Pelagius had no choice but to surrender.[132]

The Crusaders still had some leverage as Damietta was well-garrisoned. They offered the sultan a withdrawal from Damietta and an eight-year truce in exchange for allowing the Crusader army to pass, the release of all prisoners, and the return of the relic of the True Cross. Prior to the formal surrender of Damietta, the two sides would maintain hostages, among them John of Brienne and Hermann of Salza for the Franks side and a son of al-Kamil for Egypt.[133] The masters of the military orders were dispatched to Damietta, where the forces were resistant to giving up, with the news of the surrender, which happened on 8 September 1221. The Fifth Crusade was over, a dismal failure, unable to even gain the return of the piece of the True Cross.[134]

Sixth Crusade

The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229) was a military expedition to recapture the city of Jerusalem. It began seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade and involved very little actual fighting. The diplomatic maneuvering of Frederick II[135] resulted in the Kingdom of Jerusalem regaining some control over Jerusalem for much of the ensuing fifteen years. The Sixth Crusade is also known as the Crusade of Frederick II.[136]

Of all the European sovereigns, only Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, was in a position to regain Jerusalem. Frederick was, like many of the 13th-century rulers, a serial crucesignatus,[137] having taken the cross multiple times since 1215.[138] After much wrangling, an onerous agreement between the emperor and Pope Honorius III was signed on 25 July 1225 at San Germano. Frederick promised to depart on the Crusade by August 1227 and remain for two years. During this period, he was to maintain and support forces in Syria and deposit escrow funds at Rome in gold. These funds would be returned to the emperor once he arrived at Acre. If he did not arrive, the money would be employed for the needs of the Holy Land.[139] Frederick II would go on the Crusade as king of Jerusalem. He married John of Brienne's daughter Isabella II by proxy in August 1225 and they were formally married on 9 November 1227. Frederick claimed the kingship of Jerusalem despite John having been given assurances that he would remain as king. Frederick took the crown in December 1225. Frederick's first royal decree was to grant new privileges on the Teutonic Knights, placing them on equal footing as the Templars and Hospitallers.[140]

After the Fifth Crusade, the Ayyubid sultan al-Kamil became involved in civil war in Syria and, having unsuccessfully tried negotiations with the West beginning in 1219, again tried this approach,[141] offering return of much of the Holy Land in exchange for military support.[142] Becoming pope in 1227, Gregory IX was determined to proceed with the Crusade.[143] The first contingents of Crusaders then sailed in August 1227, joining with forces of the kingdom and fortifying the coastal towns. The emperor was delayed while his ships were refitted. He sailed on 8 September 1227, but before they reached their first stop, Frederick was struck with the plague and disembarked to secure medical attention. Resolved to keep his oath, he sent his fleet on to Acre. He sent his emissaries to inform Gregory IX of the situation, but the pope did not care about Frederick's illness, just that he had not lived up to his agreement. Frederick was excommunicated on 29 September 1227, branded a wanton violator of his sacred oath taken many times.[136]

Frederick made his last effort to be reconciled with Gregory. It had no effect and Frederick sailed from Brindisi in June 1228. After a stop at Cyprus, Frederick II arrived in Acre on 7 September 1228 and was received warmly by the military orders, despite his excommunication. Frederick's army was not large, mostly German, Sicilian and English.[144] Of the troops he had sent in 1227 had mostly returned home. He could neither afford nor mount a lengthening campaign in the Holy Land given the ongoing War of the Keys with Rome. The Sixth Crusade would be one of negotiation.[145]

After resolving the internecine struggles in Syria, al-Kamil's position was stronger than it was a year before when he made his original offer to Frederick. For unknown reasons, the two sides came to an agreement. The resultant Treaty of Jaffa was concluded on 18 February 1229, with al-Kamil surrendering Jerusalem, with the exception of some Muslim holy sites, and agreeing to a ten-year truce.[146] Frederick entered Jerusalem on 17 March 1229 and received the formal surrender of the city by al-Kamil's agent and the next day, crowned himself.[147] On 1 May 1229, Frederick departed from Acre and arrived in Sicily a month before the pope knew that he had left the Holy Land. Frederick obtained from the pope relief from his excommunication on 28 August 1230 at the Treaty of Ceprano.[148]

The results of the Sixth Crusade were not universally acclaimed. Two letters from the Christian side tell differing stories,[149] with Frederick touting the great success of the endeavor and the Latin patriarch painting a darker picture of the emperor and his accomplishments. On the Muslim side, al-Kamil himself was pleased with the accord, but others regarded the treaty as a disastrous event.[150] In the end, the Sixth Crusade successfully returned Jerusalem to Christian rule and had set a precedent, in having achieved success on crusade without papal involvement.

The Crusades of 1239–1241

The Crusades of 1239–1241, also known as the Barons' Crusade, were a series of crusades to the Holy Land that, in territorial terms, were the most successful since the First Crusade.[151] The major expeditions were led separately by Theobald I of Navarre and Richard of Cornwall.[152] These crusades are sometimes discussed along with that of Baldwin of Courtenay to Constantinople.[153]

In 1229, Frederick II and the Ayyubid sultan al-Kamil, had agreed to a ten-year truce. Nevertheless, Gregory IX, who had condemned this truce from the beginning, issued the papal bull Rachel suum videns in 1234 calling for a new crusade once the truce expired. A number of English and French nobles took the cross, but the crusade's departure was delayed because Frederick, whose lands the crusaders had planned to cross, opposed any crusading activity before the expiration of this truce. Frederick was again excommunicated in 1239, causing most crusaders to avoid his territories on their way to the Holy Land.[154]

The French expedition was led by Theobald I of Navarre and Hugh of Burgundy, joined by Amaury of Montfort and Peter of Dreux.[155] On 1 September 1239, Theobald arrived in Acre, and was soon drawn into the Ayyubid civil war, which had been raging since the death of al-Kamil in 1238.[156] At the end of September, al-Kamil's brother as-Salih Ismail seized Damascus from his nephew, as-Salih Ayyub, and recognised al-Adil II as sultan of Egypt. Theobald decided to fortify Ascalon to protect the southern border of the kingdom and to move against Damascus later. While the Crusaders were marching from Acre to Jaffa, Egyptian troops moved to secure the border in what became the Battle at Gaza.[157] Contrary to Theobald's instructions and the advice of the military orders, a group decided to move against the enemy without further delay, but they were surprised by the Muslims who inflicted a devastating defeat on the Franks. The masters of the military orders then convinced Theobald to retreat to Acre rather than pursue the Egyptians and their Frankish prisoners. A month after the battle at Gaza, an-Nasir Dā'ūd, emir of Kerak, seized Jerusalem, virtually unguarded. The internal strife among the Ayyubids allowed Theobald to negotiate the return of Jerusalem. In September 1240, Theobald departed for Europe, while Hugh of Burgundy remained to help fortify Ascalon.[158]

On 8 October 1240, the English expedition arrived, led by Richard of Cornwall.[159] The force marched to Jaffa, where they completed the negotiations for a truce with Ayyubid leaders begun by Theobald just a few months prior. Richard consented, the new agreement was ratified by Ayyub by 8 February 1241, and prisoners from both sides were released on 13 April. Meanwhile, Richard's forces helped to work on Ascalon's fortifications, which were completed by mid-March 1241. Richard entrusted the new fortress to an imperial representative, and departed for England on 3 May 1241.[160]

In July 1239, Baldwin of Courtenay, the young heir to the Latin Empire, travelled to Constantinople with a small army. In the winter of 1239, Baldwin finally returned to Constantinople, where he was crowned emperor around Easter of 1240, after which he launched his crusade. Baldwin then besieged and captured Tzurulum, a Nicaean stronghold seventy-five miles west of Constantinople.[161]

Although the Barons' Crusade returned the kingdom to its largest size since 1187, the gains would be dramatically reversed a few years later. On 15 July 1244, the city was reduced to ruins during the siege of Jerusalem and its Christians massacred by the Khwarazmian army. A few months later, the Battle of La Forbie permanently crippled Christian military power in the Holy Land. The sack of the city and the massacre which accompanied it encouraged Louis IX of France to organise the Seventh Crusade.[162]

The Seventh Crusade

The Seventh Crusade (1248–1254) was the first of the two Crusades led by Louis IX of France. Also known as the Crusade of Louis IX to the Holy Land, its objective was to reclaim the Holy Land by attacking Egypt, the main seat of Muslim power in the Middle East, then under as-Salih Ayyub, son of al-Kamil. The Crusade was conducted in response to setbacks in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, beginning with the loss of the Holy City in 1244, and was preached by Innocent IV in conjunction with a crusade against emperor Frederick II, the Prussian crusades and Mongol incursions.[163]

At the end of 1244, Louis was stricken with a severe malarial infection and he vowed that if he recovered he would set out for a Crusade. His life was spared, and as soon as his health permitted him, he took the cross and immediately began preparations.[164] The next year, the pope presided over First Council of Lyon, directing a new Crusade under the command of Louis. With Rome under siege by Frederick, the pope also issued his Ad Apostolicae Dignitatis Apicem, formally renewing the sentence of excommunication on the emperor, and declared him deposed from the imperial throne and that of Naples.[165]

The recruiting effort under cardinal Odo of Châteauroux was difficult, and the Crusade finally began on 12 August 1248 when Louis IX left Paris under the insignia of a pilgrim, the Oriflamme.[166] With him were queen Margaret of Provence and two of Louis' brothers, Charles I of Anjou and Robert I of Artois. Their youngest brother Alphonse of Poitiers departed the next year. They were followed by Hugh IV of Burgundy, Peter Maulcerc, Hugh XI of Lusignan, royal companion and chronicler Jean de Joinville, and an English detachment under William Longespée, grandson of Henry II of England.[167]

The first stop was Cyprus, arriving in September 1248 where they experienced a long wait for the forces to assemble. Many of the men were lost en route or to disease.[168] The Franks were soon met by those from Acre including the masters of the Orders Jean de Ronay and Guillaume de Sonnac. The two eldest sons of John of Brienne, Alsonso of Brienne and Louis of Brienne, would also join as would John of Ibelin, nephew to the Old Lord of Beirut.[169] William of Villehardouin also arrived with ships and Frankish soldiers from the Morea. It was agreed that Egypt was the objective and many remembered how the sultan's father had been willing to exchange Jerusalem itself for Damietta in the Fifth Crusade. Louis was not willing to negotiate with the infidel Muslims, but he did unsuccessfully seek a Franco-Mongol alliance, reflecting what the pope had sought in 1245.[170]

As-Salih Ayyub conducting a campaign in Damascus when the Franks invaded as he had expected the Crusaders to land in Syria. Hurrying his forces back to Cairo, he turned to his vizier Fakhr ad-Din ibn as-Shaikh to command the army that fortified Damietta in anticipation of the invasion. On 5 June 1249 the Crusader fleet began the landing and subsequent siege of Damietta. After a short battle, the Egyptian commander decided to evacuate the city.[171] Remarkably, Damietta had been seized with only one Crusader casualty.[172] The city became a Frankish city and Louis waited until the Nile floods abated before advancing, remembering the lessons of the Fifth Crusade. The loss of Damietta was a shock to the Muslim world, and as-Salih Ayyub offered to trade Damietta for Jerusalem as his father had thirty years before. The offer was rejected. By the end of October 1249 the Nile had receded and reinforcements had arrived. It was time to advance, and the Frankish army set out towards Mansurah.[173]

The sultan died in November 1249, his widow Shajar al-Durr concealing the news of her husband's death. She forged a document which appointed his son al-Muazzam Turanshah, then in Syria, as heir and Fakhr ad-Din as viceroy.[174] But the Crusade continued, and by December 1249, Louis was encamped on the river banks opposite to Mansurah.[172] For six weeks, the armies of the West and Egypt faced each other on opposite sides of the canal, leading to the Battle of Mansurah that would end on 11 February 1250 with an Egyptian defeat. Louis had his victory, but a cost of the loss of much of his force and their commanders. Among the survivors were the Templar master Guillaume de Sonnac, losing an eye, Humbert V de Beaujeu, constable of France, John II of Soissons, and the duke of Brittany, Peter Maulcerc. Counted with the dead were the king's brother Robert I of Artois, William Longespée and most of his English followers, Peter of Courtenay, and Raoul II of Coucy. But the victory would be short-lived.[175] On 11 February 1250, the Egyptians attacked again. Templar master Guillaume de Sonnac and acting Hospitaller master Jean de Ronay were killed. Alphonse of Poitiers, guarding the camp, was encircled and was rescued by the camp followers. At nightfall, the Muslims gave up the assault.[176]

On 28 February 1250, Turanshah arrived from Damascus and began an Egyptian offensive, intercepting the boats that brought food from Damietta. The Franks were quickly beset by famine and disease.[177] The Battle of Fariskur fought on 6 April 1250 would be the decisive defeat of Louis' army. Louis knew that the army must be extricated to Damietta and they departed on the morning of 5 April, with the king in the rear and the Egyptians in pursuit. The next day, the Muslims surrounded the army and attacked in full force. On 6 April, Louis' surrender was negotiated directly with the sultan by Philip of Montfort. The king and his entourage were taken in chains to Mansurah and the whole of the army was rounded up and led into captivity.[176]

The Egyptians were unprepared for the large number of prisoners taken, comprising most of Louis' force. The infirm were executed immediately and several hundred were decapitated daily. Louis and his commanders were moved to Mansurah, and negotiations for their release commenced. The terms agreed to were harsh. Louis was to ransom himself by the surrender of Damietta and his army by the payment of a million bezants (later reduced to 800,000).[178] Latin patriarch Robert of Nantes went under safe-conduct to complete the arrangements for the ransom. Arriving in Cairo, he found Turanshah dead, murdered in a coup instigated by his stepmother Shajar al-Durr. On 6 May, Geoffrey of Sergines handed Damietta over to the Moslem vanguard. Many wounded soldiers had been left behind at Damietta, and contrary to their promise, the Muslims massacred them all. In 1251, the Shepherds' Crusade, a popular crusade formed with the objective to free Louis, engulfed France.[179] After his release, Louis went to Acre where he remained until 1254. This is regarded as the end of the Seventh Crusade.[163]

The final crusades

After the defeat of the Crusaders in Egypt, Louis remained in Syria until 1254 to consolidate the crusader states.[180] A brutal power struggle developed in Egypt between various Mamluk leaders and the remaining weak Ayyubid rulers. The threat presented by an invasion by the Mongols led to one of the competing Mamluk leaders, Qutuz, seizing the sultanate in 1259 and uniting with another faction led by Baibars to defeat the Mongols at Ain Jalut. The Mamluks then quickly gained control of Damascus and Aleppo before Qutuz was assassinated and Baibers assumed control.[181]

Between 1265 and 1271, Baibars drove the Franks to a few small coastal outposts.[182] Baibars had three key objectives: to prevent an alliance between the Latins and the Mongols, to cause dissension among the Mongols (particularly between the Golden Horde and the Persian Ilkhanate), and to maintain access to a supply of slave recruits from the Russian steppes. He supported Manfred of Sicily's failed resistance to the attack of Charles and the papacy. Dissension in the crusader states led to conflicts such as the War of Saint Sabas. Venice drove the Genoese from Acre to Tyre where they continued to trade with Egypt. Indeed, Baibars negotiated free passage for the Genoese with Michael VIII Palaiologos, Emperor of Nicaea, the newly restored ruler of Constantinople.[183] In 1270 Charles turned his brother King Louis IX's crusade, known as the Eighth Crusade, to his own advantage by persuading him to attack Tunis. The crusader army was devastated by disease, and Louis himself died at Tunis on 25 August. The fleet returned to France. Prince Edward, the future king of England, and a small retinue arrived too late for the conflict but continued to the Holy Land in what is known as Lord Edward's Crusade.[184] Edward survived an assassination attempt, negotiated a ten-year truce, and then returned to manage his affairs in England. This ended the last significant crusading effort in the eastern Mediterranean.[185]

Decline and fall of the Crusader States

The years 1272–1302 include numerous conflicts throughout the Levant as well as the Mediterranean and Western European regions, and many crusades were proposed to free the Holy Land from Mamluk control. These include ones of Gregory X, Charles I of Anjou and Nicholas IV, none of which came to fruition. The major players fighting the Muslims included the kings of England and France, the kingdoms of Cyprus and Sicily, the three Military Orders and Mongol Ilkhanate. The end of Western European presence in the Holy Land was sealed with the fall of Tripoli and their subsequent defeat at the siege of Acre in 1291. The Christian forces managed to survive until the final fall of Ruad in 1302.[186]

The Holy Land would no longer be the focus of the West even though various crusades were proposed in the early years of the fourteenth century. The Knights Hospitaller would conquer Rhodes from Byzantium, making it the center of their activity for a hundred years. The Knights Templar, the elite fighting force in the kingdom, was disbanded. The Mongols converted to Islam, but disintegrated as a fighting force. The Mamluk sultanate would continue for another century. The Crusades to liberate Jerusalem and the Holy Land were over.[187]

Other crusades

The military expeditions undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries to recover the Holy Land from Muslims provided a template for warfare in other areas that also interested the Latin Church. These included the 12th and 13th century conquest of Muslim Al-Andalus by Spanish Christian kingdoms; 12th to 15th century German Northern Crusades expansion into the pagan Baltic region; the suppression of non-conformity, particularly in Languedoc during what has become called the Albigensian Crusade and for the Papacy's temporal advantage in Italy and Germany that are now known as political crusades. In the 13th and 14th centuries there were also unsanctioned, but related popular uprisings to recover Jerusalem known variously as Shepherds' or Children's crusades.[188]

Urban II equated the crusades for Jerusalem with the ongoing Catholic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula and crusades were preached in 1114 and 1118, but it was Pope Callixtus II who proposed dual fronts in Spain and the Middle East in 1122. In the spring of 1147, Eugene authorised the expansion of his mission into the Iberian peninsula, equating these campaigns against the Moors with the rest of the Second Crusade. The successful siege of Lisbon, from 1 July to 25 October 1147, was followed by the six-month siege of Tortosa, ending on 30 December 1148 with a defeat for the Moors.[189] In the north, some Germans were reluctant to fight in the Holy Land while the pagan Wends were a more immediate problem. The resulting Wendish Crusade of 1147 was partially successful but failed to convert the pagans to Christianity.[190] By the time of the Second Crusade the three Spanish kingdoms were powerful enough to conquer Islamic territory – Castile, Aragon, and Portugal.[191] In 1212 the Spanish were victorious at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa with the support of foreign fighters responding to the preaching of Innocent III. Many of these deserted because of the Spanish tolerance of the defeated Muslims, for whom the Reconquista was a war of domination rather than extermination.[192] In contrast the Christians formerly living under Muslim rule called Mozarabs had the Roman Rite relentlessly imposed on them and were absorbed into mainstream Catholicism.[193] Al-Andalus, Islamic Spain, was completely suppressed in 1492 when the Emirate of Granada surrendered.[194]

In 1147, Pope Eugene III extended Calixtus's idea by authorising a crusade on the German north-eastern frontier against the pagan Wends from what was primarily economic conflict.[195][196] From the early 13th century, there was significant involvement of military orders, such as the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Order of Dobrzyń. The Teutonic Knights diverted efforts from the Holy Land, absorbed these orders and established the State of the Teutonic Order.[197][198] This evolved the Duchy of Prussia and Duchy of Courland and Semigallia in 1525 and 1562, respectively.[199]

By the beginning of the 13th century papal reticence in applying crusades against the papacy's political opponents and those considered heretics had abated. Innocent III proclaimed a crusade against Catharism that failed to suppress the heresy itself but ruined the culture of the Languedoc.[200] This set a precedent that was followed in 1212 with pressure exerted on the city of Milan for tolerating Catharism,[201] in 1234 against the Stedinger peasants of north-western Germany, in 1234 and 1241 Hungarian crusades against Bosnian heretics.[200] The historian Norman Housley notes the connection between heterodoxy and anti-papalism in Italy.[202] Indulgence was offered to anti-heretical groups such as the Militia of Jesus Christ and the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[203] Innocent III declared the first political crusade against Frederick II's regent, Markward von Annweiler, and when Frederick later threatened Rome in 1240, Gregory IX used crusading terminology to raise support against him. On Frederick II's death the focus moved to Sicily. In 1263, Pope Urban IV offered crusading indulgences to Charles of Anjou in return for Sicily's conquest. However, these wars had no clear objectives or limitations, making them unsuitable for crusading.[204] The 1281 election of a French pope, Martin IV, brought the power of the papacy behind Charles. Charles's preparations for a crusade against Constantinople were foiled by the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, who instigated an uprising called the Sicilian Vespers. Instead, Peter III of Aragon was proclaimed king of Sicily, despite his excommunication and an unsuccessful Aragonese Crusade.[205] Political crusading continued against Venice over Ferrara; Louis IV, King of Germany when he marched to Rome for his imperial coronation; and the free companies of mercenaries.[206]

The Latin states established were a fragile patchwork of petty realms threatened by Byzantine successor states – the Despotate of Epirus, the Empire of Nicaea and the Empire of Trebizond. Thessaloniki fell to Epirus in 1224, and Constantinople to Nicaea in 1261. Achaea and Athens survived under the French after the Treaty of Viterbo.[207] The Venetians endured a long-standing conflict with the Ottoman Empire until the final possessions were lost in the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War in the 18th century. This period of Greek history is known as the Frankokratia or Latinokratia ("Frankish or Latin rule") and designates a period when western European Catholics ruled Orthodox Byzantine Greeks.[208]

The major crusades of the 14th century include: the Crusade against the Dulcinians; the Crusade of the Poor; the Anti-Catalan Crusade; the Shepherds' Crusade; the Smyrniote Crusades; the Crusade against Novgorod; the Savoyard Crusade; the Alexandrian Crusade; the Despenser's Crusade; the Mahdia, Tedelis, and Bona Crusades; and the Crusade of Nicopolis.

The threat of the expanding Ottoman Empire prompted further crusades of the 15th century. In 1389, the Ottomans defeated the Serbs at the Battle of Kosovo, won control of the Balkans from the Danube to the Gulf of Corinth, in 1396 defeated French crusaders and King Sigismund of Hungary at the Nicopolis, in 1444 destroyed a crusading Polish and Hungarian force at Varna, four years later again defeated the Hungarians at Kosovo and in 1453 captured Constantinople. The 16th century saw growing rapprochement. The Habsburgs, French, Spanish and Venetians and Ottomans all signed treaties. Francis I of France allied with all quarters, including from German Protestant princes and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[209]

Anti-Christian crusading declined in the 15th century, the exceptions were the six failed crusades against the religiously radical Hussites in Bohemia and attacks on the Waldensians in Savoy.[210] Crusading became a financial exercise; precedence was given to the commercial and political objectives. The military threat presented by the Ottoman Turks diminished, making anti-Ottoman crusading obsolete in 1699 with the final Holy League.[211][212]

Crusading movement

Prior to the 11th century, the Latin Church had developed a system for the remission and absolution of sin in return for contrition, confession, and penitential acts. Reparation through abstinence from martial activity still presented a difficulty to the noble warrior class. It was revolutionary when Gregory VII offered absolution of sin earned through the Church-sponsored violence in support of his causes, if selflessly given at the end of the century.[213][214] This was developed by subsequent Popes into the granting of plenary indulgences that reduced all God-imposed temporal penalties.[215] The papacy developed "Political Augustinianism" into attempts to remove the Church from secular control by asserting ecclesiastical supremacy over temporal polities and the Orthodox Church. This was associated with the idea that the Church should actively intervene in the world to impose "justice".[216]

A distinct ideology promoting and regulating crusading is evidenced in surviving texts. The Church defined this in legal and theological terms based on the theory of holy war and the concept of pilgrimage. Theology merged the Old Testament Israelite wars instigated and assisted by God with New Testament Christocentric views. Holy war was based on ancient ideas of just war. The fourth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo had Christianised this, and it eventually became the paradigm of Christian holy war. Theologians widely accepted the justification that holy war against pagans was good, because of their opposition to Christianity.[215] The Holy Land was the patrimony of Christ; its recovery was on behalf of God. The Albigensian Crusade was a defence of the French Church, the Northern Crusades were campaigns conquering lands beloved of Christ's mother Mary for Christianity.[217]

Inspired by the First Crusade, the crusading movement went on to define late medieval western culture and impacted the history of the western Islamic world.[218] Christendom was geopolitical, and this underpinned the practice of the medieval Church. Reformists of the 11th century urged these ideas which declined following the Reformation. The ideology continued after the 16th century with the military orders but dwindled in competition with other forms of religious war and new ideologies.[219]

Military orders

The military orders were forms of a religious order first established early in the twelfth century with the function of defending Christians, as well as observing monastic vows. The Knights Hospitaller had a medical mission in Jerusalem since before the First Crusade, later becoming a formidable military force supporting the crusades in the Holy Land and Mediterranean. The Knights Templar were founded in 1119 by a band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem.[220] The Teutonic Knights were formed in 1190 to protect pilgrims in both the Holy Land and Baltic region.[221]

The Hospitallers and the Templars became supranational organisations as papal support led to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This, in turn, led to a steady flow of new recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications in the crusader states. In time, they developed into autonomous powers in the region.[222] After the fall of Acre the Hospitallers relocated to Cyprus, then ruled Rhodes until the island was taken by the Ottomans in 1522. While there was talk of merging the Templars and Hospitallers in 1305 by Clement V, ultimately the Templars were charged with heresy and disbanded. The Teutonic Knights supported the later Prussian campaigns into the fifteenth century.

Art and architecture

According to the historian Joshua Prawer no major European poet, theologian, scholar or historian settled in the crusader states. Some went on pilgrimage, and this is seen in new imagery and ideas in western poetry. Although they did not migrate east themselves, their output often encouraged others to journey there on pilgrimage.[223]

Historians consider the crusader military architecture of the Middle East to demonstrate a synthesis of the European, Byzantine and Muslim traditions and to be the most original and impressive artistic achievement of the crusades. Castles were a tangible symbol of the dominance of a Latin Christian minority over a largely hostile majority population. They also acted as centres of administration.[224] Modern historiography rejects the 19th-century consensus that Westerners learnt the basis of military architecture from the Near East, as Europe had already experienced rapid development in defensive technology before the First Crusade. Direct contact with Arab fortifications originally constructed by the Byzantines did influence developments in the east, but the lack of documentary evidence means that it remains difficult to differentiate between the importance of this design culture and the constraints of situation. The latter led to the inclusion of oriental design features such as large water reservoirs and the exclusion of occidental features such as moats.[225]

Typically, crusader church design was in the French Romanesque style. This can be seen in the 12th-century rebuilding of the Holy Sepulchre. It retained some of the Byzantine details, but new arches and chapels were built to northern French, Aquitanian, and Provençal patterns. There is little trace of any surviving indigenous influence in sculpture, although in the Holy Sepulchre the column capitals of the south facade follow classical Syrian patterns.[226]

In contrast to architecture and sculpture, it is in the area of visual culture that the assimilated nature of the society was demonstrated. Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries the influence of indigenous artists was demonstrated in the decoration of shrines, paintings and the production of illuminated manuscripts. Frankish practitioners borrowed methods from the Byzantines and indigenous artists and iconographical practice leading to a cultural synthesis, illustrated by the Church of the Nativity. Wall mosaics were unknown in the west but in widespread use in the crusader states. Whether this was by indigenous craftsmen or learnt by Frankish ones is unknown, but a distinctive original artistic style evolved.[227]