Music of the American Civil War

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Music of the United States |

|---|

|

During the American Civil War, music played a prominent role on both sides of the conflict, Union (the North) and Confederate (the South). On the battlefield, different instruments including bugles, drums, and fifes were played to issue marching orders or sometimes simply to boost the morale of one's fellow soldiers. Singing was also employed not only as a recreational activity but as a release from the inevitable tensions that come with fighting in a war. In camp, music was a diversion away from the bloodshed, helping the soldiers deal with homesickness and boredom. Soldiers of both sides often engaged in recreation with musical instruments, and when the opposing armies were near each other, sometimes the bands from both sides of the conflict played against each other on the night before a battle.

Each side had its particular favorite tunes, while some music was enjoyed by Northerners and Southerners alike, as exemplified by United States President Abraham Lincoln's love of "Dixie", the unofficial anthem of the Confederacy. To this day, many of the songs are sung when a patriotic piece is required. The war's music also inspired music artists such as Lynyrd Skynyrd and Elvis Presley.

Development of American music

The Civil War was an important period in the development of American music. During the Civil War, when soldiers from across the country commingled, the multifarious strands of American music began to cross-fertilize each other, a process that was aided by the burgeoning railroad industry and other technological developments that made travel and communication easier. Army units included individuals from across the country, and they rapidly traded tunes, instruments, and techniques. The songs that arose from this fusion were "the first American folk music with discernible features that can be considered unique to America".[1] The war was an impetus for the creation of many songs that became and remained wildly popular; the songs were aroused by "all the varied passions (that the Civil War inspired)" and "echoed and re-echoed" every aspect of the war. John Tasker Howard has claimed that the songs from this era "could be arranged in proper sequence to form an actual history of the conflicts: its events, its principal characters, and the ideals and principles of the opposing sides".[2]

In addition to, and in conjunction with, popular songs with patriotic fervor, the Civil War era also produced a great body of brass band pieces, from both the North and the South,[3] as well as other military musical traditions like the bugle call "Taps".

Regulations

In May 1861, the United States War Department officially approved that every regiment of infantry and artillery could have a brass band with 24 members, while a cavalry regiment could have one of sixteen members. The Confederate army would also have brass bands. This was followed by a Union army regulation of July 1861 requiring every infantry, artillery, or cavalry company to have two musicians and for there to be a twenty-four man band for every regiment.[4] The July 1861 requirement was ignored as the war dragged on, as riflemen were more needed than musicians. In July 1862 the brass bands of the Union were disassembled by the adjutant general, although the soldiers that comprised them were sometimes re-enlisted and assigned to musician roles. A survey in October 1861 found that 75% of Union regiments had a band.[4] By December 1861 the Union army had 28,000 musicians in 618 bands; a ratio of one soldier out of 41 who served the army was a musician, and the Confederate army was believed to have a similar ratio.[5] Musicians were often given special privileges. Union general Philip Sheridan gave his cavalry bands the best horses and special uniforms, believing "Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war".[6]

Musicians on the battlefield were drummers and buglers, with an occasional fifer. Buglers had to learn forty-nine separate calls just for infantry, with more needed for cavalry. These ranged from battle commands to calls for meal time.[7] Some of these required musicians were drummer boys not even in their teens, which allowed an adult man to instead be a foot soldier. The most notable of these under aged musicians was John Clem, also known as "Johnny Shiloh". Union drummers wore white straps to support their drums. The drum and band majors wore baldrics to indicate their status; after the war, this style would be emulated in civilian bands. Drummers would march to the right of a marching column. Similar to buglers, drummers had to learn 39 different beats: fourteen for general use, and 24 for marching cadence. However, buglers were given greater importance than drummers.[8]

On the battlefield

Whole songs were sometimes played during battles. The survivors of the disastrous Pickett's Charge returned under the tune "Nearer My God to Thee".[9] At the Battle of Five Forks, Union musicians under orders from Sheridan played Stephen Foster's minstrel song "Nelly Bly" while being shot at on the front lines.[9] Samuel P. Heintzelman, the commander of the III Corps, saw many of his musicians standing at the back lines at the Battle of Williamsburg, and ordered them to play anything.[9] Their music rallied the Union forces, forcing the Confederate to withdraw. It was said that music was the equivalent of "a thousand men" on one's side. Robert E. Lee himself said, "I don't think we could have an army without music."[10]

Sometimes, musicians were ordered to leave the battlefront and assist the surgeons. One notable time was the 20th Maine's musicians at Little Round Top. As the rest of the regiment were driving back wave after wave of Confederates, the musicians of the regiment were not just performing amputations, but doing it in a very quick manner.[11][12]

In camp

Many soldiers brought musical instruments from home to pass the time at camp. Banjos, fiddles, and guitars were particularly popular. Aside from drums, the instruments Confederates played were either acquired before the war or imported, due to the lack of brass and the industry to make such instruments.[11][13]

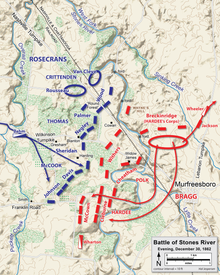

Musical duels between the two sides were common, as they heard each other as the music traveled across the countryside. The night before the Battle of Stones River, bands from both sides dueled with separate songs until both sides started playing "Home! Sweet Home!", at which time soldiers on both sides started singing together as one.[14] A similar situation occurred in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the winter of 1862–63. On a cold afternoon, a Union band started playing Northern patriotic tunes; a Southern band responded by playing Southern patriotic tunes. This back and forth continued into the night, until at the end both sides played "Home! Sweet Home!" simultaneously, to the cheers of both sides' forces.[11] In a third instance, in the spring of 1863, the opposing armies were on the opposite sides of the Rappahannock River in Virginia, when the different sides played their patriotic tunes, and at taps one side played "Home! Sweet Home!", and the other joined in, creating "cheers" from both sides that echoed throughout the hilly countryside.[15]

Both sides sang "Maryland, My Maryland", although the lyrics were slightly different. Another popular song for both was "Lorena". "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" was written in 1863 by Patrick Gilmore, an immigrant from Ireland, and was also enjoyed by both sides.[16][17]

Homefront

The first song written for the war, "The First Gun Is Fired", was first published and distributed three days after the Battle of Fort Sumter. George F. Root, who wrote it, is said to have produced the most songs of anyone about the war, over thirty in total.[18] Lincoln once wrote a letter to Root, saying, "You have done more than a hundred generals and a thousand orators."[19] Other songs played an important role in convincing northern whites that African Americans were willing to fight and wanted freedom, for instance Henry Clay Work's 1883 "Babylon Is Fallen" and Charles Halpine's "Sambo's Right to Be Kilt".[20]

The southern states had long lagged behind northern states in producing common literature. With the advent of war, Southern publishers were in demand. These publishers, based largely in five cities (Charleston, South Carolina; Macon, Georgia; Mobile, Alabama; Nashville, Tennessee; and New Orleans, Louisiana), produced five times more printed music than they did literature.[21]

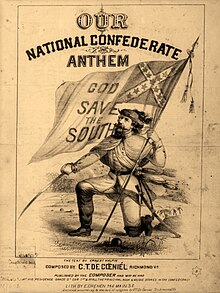

In the Confederate States of America, "God Save the South" was the official national anthem. However, "Dixie" was the most popular.[17] United States President Abraham Lincoln said he loved "Dixie" and wanted to hear it played, saying "as we had captured the rebel army, we had also captured the rebel tune".[22] At an April 9, 1865, rally, the band director was surprised when Lincoln requested that the band play "Dixie". Lincoln said, "That tune is now Federal property ... good to show the rebels that, with us in power, they will be free to hear it again." The other prominent tune was "The Bonnie Blue Flag", which, like "Dixie", was written in 1861, unlike Union popular tunes which were written throughout the war.[23]

The United States did not have a national anthem at this time ("The Star-Spangled Banner" would not be recognized as such until the twentieth century). Union soldiers frequently sang the "Battle Cry of Freedom", and the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" was considered the north's most popular song.[17]

African American music

Music sung by African-Americans changed during the war. The theme of escape from bondage became especially important in spirituals sung by blacks, both by slaves singing among themselves on plantations and for free and recently freed blacks singing to white audiences. New versions of songs such as "Hail Mary", "Michael Row the Boat Ashore", and "Go Down Moses" emphasized the message of freedom and the rejection of slavery.[24] Many new slave songs were sung as well, the most popular being, "Many Thousands Go", which was frequently sung by slaves fleeing plantations to Union Army camps.[25] Several attempts were made to publish slave songs during the war. The first was the publishing of sheet music to "Go Down Moses" by Reverend L. C. Lockwood in December 1861 based on his experience with escaped slaves in Fort Monroe, Virginia, in September of that year. In 1863, the Continental Monthly published a sampling of spirituals from South Carolina in an article titled, "Under the Palmetto".[26]

The white colonel of the all-black First South Carolina, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, noted that when blacks knew that whites were listening, they changed the way they were sung, and historian Christian McWhiter noted that African Americans "used their music to reshape white perceptions and foster a new image of black culture as thriving and ready for freedom".[27] In Port Royal, escaped slaves learned the anthem, "America" in secret, never singing it in front of whites. When the Emancipation Proclamation was passed, a celebration was held, and in a surprise to white onlookers, contrabands began singing the anthem, using the song to express their new status.[28] The most popular white songs among slaves were "John Brown's Body" and H. C. Work's "Kingdom Coming",[29] and as the war continued, the lyrics African Americans sung changed, with vagueness and coded language dropped and including open expressions of their new roles as soldiers and citizens.[30]

Slave owners in the south responded by restricting singing on plantations and imprisoning singers of songs supporting emancipation or the North.[31] Confederate supporters also looked to music sung by slaves for signs of loyalty. Several Confederate regimental bands included slaves, and Confederates arranged slaves to sing and dance to show how happy they were. Slave performer Thomas Greene Bethune, known as Blind Tom, frequently played pro-Confederate songs such as "Maryland, My Maryland" and "Dixie" and dropped, "Yankee Doodle" from his performances.[32]

Different versions

Although certain songs were identified with one particular side of the war, sometimes the other would adapt the song for their use. A Southern revision of "The Star-Spangled Banner" was used, entitled "The Southern Cross". In an example of the different lyrics, where the "Banner" had "O say does that Star Spangled Banner yet wave", the "Cross" had "'Tis the Cross of the South, which shall ever remain".[33] Another Confederate version of "The Star-Spangled Banner", called "The Flag of Secession", replaced the same verse with "and the flag of secession in triumph doth wave".[22] Even a song from the American Revolutionary War was adapted, as the tune "Yankee Doodle" was changed to "Dixie Doodle", and started with "Dixie whipped old Yankee Doodle early in the morning".[34] The Union's "Battle Cry of Freedom" was also altered, with the original lines of "The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah! Down with the traitor, up with the star" being changed to "Our Dixie forever! She's never at a loss! Down with the eagle and up with the cross!"[35]

The Union also adapted Southern songs. In a Union variation of "Dixie", instead of the line "I wish I was in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten, Look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land", it was changed to "Away down South in the land of traitors, Rattlesnakes and alligators, Right away, come away, right away, come away".[36] "John Brown's Body" (originally titled "John Brown") was originally written for a soldier at Fort Warren in Boston in 1861. It was sung to the tune of "Glory, Hallelujah" and was later used by Julia Ward Howe for her famous poem, "Battle Hymn of the Republic".[37]

Classical music

- A Lincoln Portrait (1942), by Aaron Copland, for narrator and orchestra. The subject is Lincoln's words. Contains excerpts from his 1862 annual address to Congress, the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, and the Gettysburg Address. The narrator is usually a distinguished person the orchestra wishes to honor; among them have been Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and Barack Obama.

- "The Battle of Shiloh" (1886), by C. L. Barnhouse, march for military band. The subject is the battle of the same name.

- Names from the War (1961), by Alec Wilder, for narrator with chorus, woodwinds, and brass. Sets to music a long poem of the same name by Civil War historian Bruce Catton. 100 years later, what remains are the names.

Legacy

The music derived from this war was of greater quantity and variety than from any other war involving America.[38] Songs came from a variety of sources. "Battle Hymn of the Republic" borrowed its tune from a song sung at Methodist revivals. "Dixie" was a minstrel song that Daniel Emmett adapted from two Ohio black singers named Snowden.[39] After the Civil War, American soldiers would continue to sing "Battle Hymn of the Republic" until World War II.[40]

The Southern rock style of music has often used the Confederate Battle Flag as a symbol of the musical style. "Sweet Home Alabama" by Lynyrd Skynyrd was described as a "vivid example of a lingering Confederate mythology in Southern culture".[41]

A ballad from the war, "Aura Lee", would become the basis of the song "Love Me Tender" by Elvis Presley. Presley also sang "An American Trilogy", which was described as "smoothing" out "All My Trials", the "Battle Hymn of the Republic", and "Dixie" of its divisions, although "Dixie" still dominated the piece.[42]

In 2013, a compilation album by current popular musicians, like Jorma Kaukonen, Ricky Skaggs, and Karen Elson, was released with the title Divided & United: The Songs of the Civil War.[43]

Songs published per year

w. = Words by

m. = Music by

1861

- "The First Gun is Fired", w.m. George F. Root

- "The Bonnie Blue Flag", w. Mrs. Annie Chamber-Ketchum, m. Harry MacCarthy

- "Dixie", w. Dan Emmett a. C. S. Grafully

- "John Brown's Body", w. anonymous m. William Steffe (came to be the unofficial theme song of black soldiers)

- "Maryland, My Maryland", w. James Ryder Randall m. Walter de Mapers (Music "Mini est Propositum" 12th century)

- "The Vacant Chair", w. Henry S. Washburne m. George Frederick Root

1862

- "Here's Your Mule", C. D. Benson

- "Battle Cry of Freedom", George F. Root

- "Battle Hymn of the Republic", Julia Ward Howe

1863

- "All Quiet Along the Potomac Tonight", w.m. John Hill Hewitt

- "Just Before the Battle, Mother", by George F. Root

- "Mother Would Comfort Me", w.m. Charles C. Sawyer

- "Tenting on the Old Camp Ground", w.m. Walter Kittredge

- "Weeping Sad and Lonely", w. Charles Carroll Sawyer m. Henry Tucker

- "When Johnny Comes Marching Home", by Patrick Gilmore

- "You Are Going to the Wars, Willie Boy!", w.m. John Hill Hewitt

- "The Young Volunteer", w.m. John Hill Hewitt

1864

- "Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! (The Boys Are Marching)", w.m. George F. Root

- "Pray, Maiden, Pray!", w. A. W. Kercheval, m. A. J. Turner

1865

- "Jeff in Pettycoats", w.m. Henry Tucker

- "Marching Through Georgia", w.m. Henry Clay Work

- "Good Bye, Old Glory", w. L. J. Bates, m. George Frederick Root

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Struble, p. xvii

- ^ Howard, John Tasker, cited in Ewen, p. 19 (no specific source given)

- ^ "Band Music from the Civil War Era", Library of Congress

- ^ a b Lanning p. 243

- ^ Lanning p. 243, Vaughan pp. 194, 195

- ^ Lanning, p. 244

- ^ Amedeo, p. 127; Miller, p. 92

- ^ Lanning p. 243; Miller p. 96

- ^ a b c Lanning p. 244

- ^ Lanning pp. 243, 244

- ^ a b c "Music of the Civil War", National Park Service

- ^ Turner p. 151; Vaughan p. 195

- ^ Heidler p. 1173; Miller p. 190

- ^ Amedeo p. 257; Vaughan p. 194

- ^ Branham p. 131

- ^ Amedeo, pp. 77, 127

- ^ a b c Lanning p. 245

- ^ Kelley p. 30; Silber p. 7

- ^ Branham p. 132

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 148

- ^ Harwell, pp. 3, 4

- ^ a b Branham p. 130

- ^ Silber, p. 8

- ^ McWhirter 2012, pp. 149–150, 157

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 151

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 155–156

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 152

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 158–159

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 159

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 163

- ^ McWhirter 2012, pp. 152–153

- ^ McWhirter 2012, p. 154

- ^ Harwell pp. 64, 65

- ^ Harwell, p. 67

- ^ Silber p. 10

- ^ Van Deburg p. 109

- ^ Hall, p. 4

- ^ Silber, p. 4

- ^ Heidler pp. 191, 607

- ^ Ravitch p. 257

- ^ Kaufman pp. x, 81

- ^ Amedeo, p. 111, Kaufman, p. 83

- ^ Doughtery, Steve, "Civil War Pop Music: Divided & United: On a new CD, contemporary artists revive the era's songs", The Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2013

References

- Amedeo, Michael (2007). Civil War: Untold stories of the Blue and the Gray. West Side Publications. ISBN 978-1-4127-1418-1.

- Branham, Robert J. (2002). Sweet Freedom's Song: "My Country 'tis of Thee" and Democracy in America. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-513741-8.

- Ewen, David (1957). Panorama of American Popular Music. Prentice Hall.

- Hall, Roger Lee (2012). Glory, Hallelujah: Civil War Songs and Hymns. PineTree Press.

- Harwell, Richard B. (1950). Confederate Music. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 309959.

- Heidler, David (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Kaufman, Will (2006). The Civil War in American Culture. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1935-6.

- Kelley, Bruce (2004). "An Overview of Music of the Civil War Era" Bugle Resounding. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8131-2375-5.

- Lanning, Michael (2007). The Civil War 100. Sourcebooks. ISBN 978-1-4022-1040-2.

- McWhirter, Christian (2012). Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469613673.

- Miller, David (2001). Uniforms, Weapons, and Equipment of the Civil War. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 1-84065-257-8.

- Ravitch, Diane (2000). The American Reader: Words that Moved a Nation. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-273733-3.

- Silber, Irwin (1995). Songs of the Civil War. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28438-7.

- Struble, John Warthen (1995). The History of American Classical Music. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-2927-X.

- Turner, Thomas Reed (2007). 101 Things You Didn't Know about the Civil War. Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-59869-320-1.

- Van Deburg, William L. (1984). Slavery & Race in American Popular Culture. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-09634-3.

- Vaughan, Donald (2000). The Everything Civil War Book. Holbrook, Massachusetts: Adams Media Corporation. ISBN 1-58062-366-2.

Further reading

- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861–1865 (First ed.). Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0228-6.

- Clarke, Donald (1995). The Rise and Fall of Popular Music. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-11573-3.

- Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82535-X.

- Knouse, Nola Reed "Music from the Band Books of the 26th Infantry Regiment, NC Troops, C.S.A.". Liner notes essay. New World Records.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans. New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 206–212. ISBN 0-393-97141-4.

External links

- "Collection: Band Music From the Civil War Era". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 13, 2005.

- The short film A Nation Sings (1963) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Singing the Songs of Zion: Soldier's Hymn Collections and Hymn Singing in the American Civil War

- Civil War songs and hymns

- American Song Sheets, Duke University Libraries Digital Collections – includes images and text of over 1,500 Civil War song sheets

- Civil War-era pictorial envelopes and song sheets at the University of Maryland Libraries