Kurtuluş

Kurtuluş | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood | |

| Coordinates: 41°02′54″N 28°58′51″E / 41.04845°N 28.98095°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Marmara |

| Province | Istanbul |

| District | Şişli |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 34375, 34377, 34379 |

| Area code | 0212 |

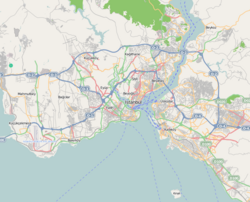

Kurtuluş is a neighbourhood of the Şişli district of Istanbul that was originally called Tatavla, meaning 'stables' in Greek (Greek: Ταταύλα). The modern Turkish name means "liberation", "salvation", "independence" or "deliverance". On 13 April 1929, six years after the Republic of Turkey was founded, a fire swept through the neighbourhood and largely destroyed it, with 207 houses going up in flames. The name was changed to Kurtuluş to mark the rebuilding of the area.

Once a predominantly Greek Orthodox and Armenian neighbourhood,[1][2] its population today mostly consists of Turks who moved there after the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923. There is still a small population or Greeks, Armenians and Jews, as well as some Kurds who are relatively recent economic migrants.

Kurtuluş is served by the Osmanbey Metro station and innumerable buses from Taksim. It is adjacent to Pangaltı, Feriköy and Dolapdere.

History

The quarter started life in the 16th century as a residential area for Greeks from the island of Chios who were settled here to work in the principal dockyards of the Ottoman Empire in the neighbouring Kasımpaşa quarter; they originally lived in Kasımpaşa but retreated uphill to a new area when their church there was turned into a mosque.[citation needed][3] In 1793 Sultan Selim III decreed that only Greeks would be allowed to live in Tatavla, a distinction it shared with the small Aegean town of Ayvalık.[4]

In 1832, a fire completely destroyed the neighbourhood, with 600 houses and 30 shops going up in flames. During the 19th century Tatavla's population reached around 20,000 and it hosted several Orthodox churches (Hagios Demetrios, Hagios Georgios and Hagios Eleftherios), schools and tavernas;[5] it was nicknamed Little Athens because of its Greek character.[5] It was typically a residential area for Greeks of more modest income. Nevertheless, a number of grand houses were built in the late 19th century, some of which still stand today, especially along Kurtuluş Caddesi.

Despite the turmoil of the Balkan War, followed by World War I and the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and then the devastating fire, the neighbourhood continued to be home to a large Greek population (as well as a significant Armenian and Jewish population). However, the riots of 1955 persuaded most of the Greeks that the time had come to emigrate.

Culture

Tatavla used to be famous for the lively Baklahorani carnival, an annual event organised by the Greek Orthodox community on Clean Monday, the last Monday before Lent. It took place during 19th century and perhaps earlier.[6] This was banned by the Turkish authorities in 1943, but was revived in 2010.[7]

A vivid description of pre-First World War Tatavla is to be found in Maria Iordanidou's 1963 novel Loxandra, which is based on the experiences of her grandmother.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Candar, Tuba (2017). Hrant Dink: An Armenian Voice of the Voiceless in Turkey. Taylor & Francis. p. 362. ISBN 9781351514781.

- ^ Eckhardt, Robyn (2017). Istanbul and Beyond: Exploring the Diverse Cuisines of Turkey. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 35. ISBN 9780544444317.

- ^ Yale 1 Tonguç 2, Pat 1 Saffet Emre 2 (2010). Istanbul The Ultimate Guide (1st ed.). Istanbul: Boyut. p. 353. ISBN 9789752307346.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Yale 1 Tonguç 2, Pat 1 Saffet Emre 2 (2010). Istanbul The Ultimate Guide (1st ed.). Istanbul: Boyut. p. 353. ISBN 9789752307346.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Didem Danis, Ebru Kayaalp. "Elmadag: A Neighborhood in Flux" (PDF). Institut Français D'Etudes Anatoliennes GEORGES DUMEZIL. p. 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ "Baklahorani Carnival". Greek Minority of Istanbul. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Mullins, Ansel. "Reviving Carnival in Istanbul". New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Loxandra, English translation 2017, by Maria Iordanidou, pub. Harvey, pp. e.g. 26-28

External links

- Şişli Belediyesi (Şişli Municipality). Tarihçe (Brief history). https://web.archive.org/web/20100302202602/http://www.sislibelediyesi.com/yeni/sisli/t1.asp?PageName=tarihce Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- A Journey through Kurtuluş, a Mirror of Turkey Old and New, Evan Pheiffer, 2 April 2020. https://www.resetdoc.org/story/a-journey-through-kurtulus/. Retrieved 16 October 2020.