History of the Teller–Ulam design

The Teller–Ulam design is a technical concept behind modern thermonuclear weapons, also known as hydrogen bombs. The design – the details of which are military secrets and known to only a handful of major nations – is [citation needed] believed to be used in virtually all modern nuclear weapons that make up the arsenals of the major nuclear powers.

History

Teller's "Super"

The idea of using the energy from a fission device to begin a fusion reaction was first proposed by the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi to his colleague Edward Teller in the fall of 1941 during what would soon become the Manhattan Project, the World War II effort by the United States and United Kingdom to develop the first nuclear weapons. Teller soon was a participant at Robert Oppenheimer's 1942 summer conference on the development of a fission bomb held at the University of California, Berkeley, where he guided discussion towards the idea of creating his "Super" bomb, which would hypothetically be many times more powerful than the yet-undeveloped fission weapon. Teller assumed creating the fission bomb would be nothing more than an engineering problem, and that the "Super" provided a much more interesting theoretical challenge.

For the remainder of the war the effort was focused on first developing fission weapons. Nevertheless, Teller continued to pursue the "Super", to the point of neglecting work assigned to him for the fission weapon at the secret Los Alamos lab where he worked. (Much of the work Teller declined to do was given instead to Klaus Fuchs, who was later discovered to be a spy for the Soviet Union.[1]: 430 ) Teller was given some resources with which to study the "Super", and contacted his friend Maria Göppert-Mayer to help with laborious calculations relating to opacity. The "Super", however, proved elusive, and the calculations were incredibly difficult to perform, especially since there was no existing way to run small-scale tests of the principles involved (in comparison, the properties of fission could be more easily probed with cyclotrons, newly created nuclear reactors, and various other tests).

Even though they had witnessed the Trinity test, after the atomic bombings of Japan scientists at Los Alamos were surprised by how devastating the effects of the weapon had been.[2]: 35 Many of the scientists rebelled against the notion of creating a weapon thousands of times more powerful than the first atomic bombs. For the scientists the question was in part technical—the weapon design was still quite uncertain and unworkable—and in part moral: such a weapon, they argued, could only be used against large civilian populations, and could thus only be used as a weapon of genocide. Many scientists, such as Teller's colleague Hans Bethe (who had discovered stellar nucleosynthesis, the nuclear fusion that takes place in stars), urged that the United States should not develop such weapons and set an example towards the Soviet Union. Promoters of the weapon, including Teller and Berkeley physicists Ernest Lawrence and Luis Alvarez, argued that such a development was inevitable, and to deny such protection to the people of the United States—especially when the Soviet Union was likely to create such a weapon itself—was itself an immoral and unwise act. Still others, such as Oppenheimer, simply thought that the existing stockpile of fissile material was better spent in attempting to develop a large arsenal of tactical atomic weapons rather than potentially squandered on the development of a few massive "Supers".[3]

In any case, work slowed greatly at Los Alamos, as some 5,500 of the 7,100 scientists and related staff who had been there at the conclusion of the war left to go back to their previous positions at universities and laboratories.[2]: 89–90 A conference was held at Los Alamos in 1946 to examine the feasibility of building a Super; it concluded that it was feasible, but there were a number of dissenters to that conclusion.[2]: 91

When the Soviet Union exploded their own atomic bomb (dubbed "Joe 1" by the US) in August 1949, it caught Western analysts off guard, and over the next several months there was an intense debate within the US government, military, and scientific communities on whether to proceed with the far-more-powerful Super.[2]: 1–2 On January 31, 1950, US President Harry S. Truman ordered a program to develop a hydrogen bomb.[1]: 406–408

Many scientists returned to Los Alamos to work on the "Super" program, but the initial attempts still seemed highly unworkable. In the "classical Super," it was thought that the heat alone from the fission bomb would be used to ignite the fusion material, but that proved to be impossible. For a while, many scientists thought (and hoped) that the weapon itself would be impossible to construct.[2]: 91

Ulam's and Teller's contributions

The exact history of the Teller–Ulam breakthrough is not completely known, partly because of numerous conflicting personal accounts and also by the continued classification of documents that would reveal which was closer to the truth. Previous models of the "Super" had apparently placed the fusion fuel either surrounding the fission "trigger" (in a spherical formation) or at the heart of it (similar to a "boosted" weapon) in the hopes that the closer the fuel was to the fission explosion, the higher the chance it would ignite the fusion fuel by the sheer force of the heat generated.

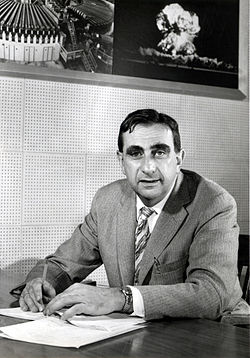

In 1951, after many years of fruitless labor on the "Super", a breakthrough idea from the Polish émigré mathematician Stanislaw Ulam was seized upon by Teller and developed into the first workable design for a megaton-range hydrogen bomb. This concept, now called "staged implosion" was first proposed in a classified scientific paper, On Heterocatalytic Detonations I. Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors[note 1][4] by Teller and Ulam on March 9, 1951. The exact amount of contribution provided respectively from Ulam and Teller to what became known as the "Teller–Ulam design" is not definitively known in the public domain—the degree of credit assigned to Teller by his contemporaries is almost exactly commensurate with how well they thought of Teller in general. In an interview with Scientific American from 1999, Teller told the reporter:

I contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea which I already had worked out and difficulty getting people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When it then came to defending that paper and really putting work into it, he refused. He said, "I don't believe in it."[5]

The issue is controversial. Bethe in his “Memorandum on the History of the Thermonuclear Program” (1952) cited Teller as the discoverer of an “entirely new approach to thermonuclear reactions”, which “was a matter of inspiration” and was “therefore, unpredictable” and “largely accidental.”[6] At the Oppenheimer hearing, in 1954, Bethe spoke of Teller's “stroke of genius” in the invention of the H-bomb.[7] And finally in 1997 Bethe stated that “the crucial invention was made in 1951, by Teller.” [8]

Other scientists (antagonistic to Teller, such as J. Carson Mark) have claimed that Teller would have never gotten any closer without the idea of Ulam. The nuclear weapons designer Ted Taylor was clear about assigning credit for the basic staging and compression ideas to Ulam, while giving Teller the credit for recognizing the critical role of radiation as opposed to hydrodynamic pressure.[9]

Priscilla Johnson McMillan in her book The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer: And the Birth of the Modern Arms Race, writes that Teller sought to "conceal the role" of Ulam, and that only "radiation implosion" was Teller's idea. Teller went as far as refusing to sign the patent application because it would need Ulam's signature. Thomas Powers writes that "of course the bomb designers all knew the truth, and many considered Teller the lowest, most contemptible kind of offender in the world of science, a stealer of credit".[10]

Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb", a title which he did not seek to discourage. Many of Teller's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a part in, and in response, with encouragement from Enrico Fermi, Teller authored an article titled "The Work of Many People," which appeared in Science magazine in February 1955, emphasizing that he was not alone in the weapon's development (he would later write in his memoirs that he had told a "white lie" in the 1955 article, and would imply that he should receive full credit for the weapon's invention).[11] Hans Bethe, who also participated in the hydrogen bomb project, once said, "For the sake of history, I think it is more precise to say that Ulam is the father, because he provided the seed, and Teller is the mother, because he remained with the child. As for me, I guess I am the midwife."[12]: 166

The Teller–Ulam breakthrough—the details of which are still classified—was apparently the separation of the fission and fusion components of the weapons, and to use the radiation produced by the fission bomb to first compress the fusion fuel before igniting it. Some sources have suggested that Ulam initially proposed compressing the secondary through the shock waves generated by the primary and that it was Teller who then realized that the radiation from the primary would be able to accomplish the task (hence "radiation implosion"). However, compression alone would not have been enough and the other crucial idea, staging the bomb by separating the primary and secondary, seems to have been exclusively contributed by Ulam. The elegance of the design impressed many scientists, to the point that some who previously wondered if it were feasible suddenly believed it was inevitable and that it would be created by both the US and the Soviet Union. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally opposed to the project, called the idea "technically sweet." The "George" shot of Operation Greenhouse in 1951 tested the basic concept for the first time on a very small scale (and the next shot in the series, "Item," was the first boosted fission weapon), raising expectations to a near certainty that the concept would work.

On November 1, 1952, the Teller–Ulam configuration was tested in the "Ivy Mike" shot at an island in the Enewetak atoll, with a yield of 10.4 megatons of TNT (44 PJ) (over 450 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki during World War II). The device, dubbed the Sausage, used an extra-large fission bomb as a "trigger" and liquid deuterium, kept in its liquid state by 20 short tons (18 tonnes) of cryogenic equipment, as its fusion fuel, and it had a mass of around 80 short tons (73 tonnes) altogether. An initial press blackout was attempted, but it was soon announced that the US had detonated a megaton-range hydrogen bomb.

The elaborate refrigeration plant necessary to keep its fusion fuel in a liquid state meant that the "Ivy Mike" device was too heavy and too complex to be of practical use. The first deployable Teller–Ulam weapon in the US would not be developed until 1954, when the liquid deuterium fuel of the "Ivy Mike" device would be replaced with a dry fuel of lithium deuteride and tested in the "Castle Bravo" shot (the device was codenamed the Shrimp). The dry lithium mixture performed much better than had been expected, and the "Castle Bravo" device that was detonated in 1954 had a yield two-and-a-half times greater than had been expected (at 15 Mt (63 PJ), it was also the most powerful bomb ever detonated by the United States). Because much of the yield came from the final fission stage of its 238

U

tamper,[13] it generated much nuclear fallout, which caused one of the worst nuclear accidents in US history after unforeseen weather patterns blew it over populated areas of the atoll and Japanese fishermen on board the Daigo Fukuryu Maru.

After an initial period focused on making multi-megaton hydrogen bombs, efforts in the United States shifted towards developing miniaturized Teller–Ulam weapons which could outfit Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles and Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles. The last major design breakthrough in this respect was accomplished by the mid-1970s, when versions of the Teller–Ulam design were created which could fit on the end of a small MIRVed missile.

Soviet research

In the Soviet Union, the scientists working on their own hydrogen bomb project also ran into difficulties in developing a megaton-range fusion weapon. Because Klaus Fuchs had only been at Los Alamos at a very early stage of the hydrogen bomb design (before the Teller–Ulam configuration had been completed), none of his espionage information was of much use, and the Soviet physicists working on the project had to develop their weapon independently.

The first Soviet fusion design, developed by Andrei Sakharov and Vitaly Ginzburg in 1949 (before the Soviet Union had a working fission bomb), was dubbed the Sloika, after a Russian layered puff pastry, and was not of the Teller–Ulam configuration, but rather used alternating layers of fissile material and lithium deuteride fusion fuel spiked with tritium (this was later dubbed Sakharov's "First Idea"). Though nuclear fusion was technically achieved, it did not have the scaling property of a staged weapon, and their first hydrogen bomb test, Joe 4, is considered a hybrid fission/fusion device more similar to a large boosted fission weapon than a Teller–Ulam weapon (though using an order of magnitude more fusion fuel than a boosted weapon). Detonated in 1953 with a yield equivalent to 400 kt (1,700 TJ) (only 15%–20% from fusion), the Sloika device did, however, have the advantage of being a weapon which could actually be delivered to a military target, unlike the "Ivy Mike" device, though it was never widely deployed. Teller had proposed a similar design as early as 1946, dubbed the "Alarm Clock" (meant to "wake up" research into the "Super"), though it was calculated to be ultimately not worth the effort and no prototype was ever developed or tested.

Attempts to use a Sloika design to achieve megaton-range results proved unfeasible in the Soviet Union as it had in the calculations done in the US, but its value as a practical weapon since it was 20 times more powerful than their first fission bomb, should not be underestimated. The Soviet physicists calculated that at best the design might yield a single megaton of energy if it was pushed to its limits. After the US tested the "Ivy Mike" device in 1952, proving that a multimegaton bomb could be created, the Soviet Union searched for an additional design and continued to work on improving the Sloika (the "First Idea"). The "Second Idea", as Sakharov referred to it in his memoirs, was a previous proposal by Ginzburg in November 1948 to use lithium deuteride in the bomb, which would, by the bombardment by neutrons, produce tritium.[14]: 299, 314 In late 1953, physicist Viktor Davidenko achieved the first breakthrough, that of keeping the primary and the secondary parts of the bombs in separate pieces ("staging"). The next breakthrough was discovered and developed by Sakharov and Yakov Zeldovich, that of using the X-rays from the fission bomb to compress the secondary before fusion ("radiation implosion"), in the spring of 1954. Sakharov's "Third Idea", as the Teller–Ulam design was known in the Soviet Union, was tested in the shot "RDS-37" in November 1955 with a yield of 1.6 Mt (6.7 PJ).

If the Soviet Union had been able to analyze the fallout data from either the "Ivy Mike" or "Castle Bravo" tests, they could have been able to discern that the fission primary was being kept separate from the fusion secondary, a key part of the Teller–Ulam device, and perhaps that the fusion fuel had been subjected to high amounts of compression before detonation.[15] One of the key Soviet bomb designers, Yuli Khariton, later said:

At that time, Soviet research was not organized on a sufficiently high level, and useful results were not obtained, although radiochemical analyses of samples of fallout could have provided some useful information about the materials used to produce the explosion. The relationship between certain short-lived isotopes formed in the course of thermonuclear reactions could have made it possible to judge the degree of compression of the thermonuclear fuel, but knowing the degree of compression would not have allowed Soviet scientists to conclude exactly how the exploded device had been made, and it would not have revealed its design.[16]: 20

Sakharov stated in his memoirs that though he and Davidenko had fallout dust in cardboard boxes several days after the "Mike" test with the hope of analyzing it for information, a chemist at Arzamas-16 (the Soviet weapons laboratory) had mistakenly poured the concentrate down the drain before it could be analyzed. Only in the fall of 1952 did the Soviet Union set up an organized system for monitoring fallout data. Nonetheless, the memoirs also say that the yield from one of the American tests, which became an international incident involving Japan, told Sakharov that the US design was much better than theirs, and he decided that they must have exploded a separate fission bomb and somehow used its energy to compress the lithium deuteride. He then turned his focus to finding a way for an explosion to one side to be used to compress the ball of fusion fuel within 5% of symmetry, which he realised could be achieved by focusing the X-rays. [14]

The Soviet Union demonstrated the power of the "staging" concept in October 1961 when they detonated the massive and unwieldy Tsar Bomba, a 50 Mt (210 PJ) hydrogen bomb which derived almost 97% of its energy from fusion rather than fission—its uranium tamper was replaced with one of lead shortly before firing, in an effort to prevent excessive nuclear fallout. Had it been fired in its "full" form, it would have yielded at around 100 Mt (420 PJ). The weapon was technically deployable (it was tested by dropping it from a specially modified bomber), but militarily impractical, and was developed and tested primarily as a show of Soviet strength. It is the largest nuclear weapon developed and tested by any country.[citation needed]

Other countries

United Kingdom

The details of the development of the Teller–Ulam design in other countries are less well known. In any event, the United Kingdom initially had difficulty in its development of it and failed in its first attempt in May 1957 (its "Grapple I" test failed to ignite as planned, but much of its energy came from fusion in its secondary). However, it succeeded in its second attempt in its November 1957 "Grapple X" test, which yielded 1.8 Mt. The British development of the Teller–Ulam design was apparently independent, but it was allowed to share in some US fallout data which may have been useful. After the successful detonation of a megaton-range device and thus its practical understanding of the Teller–Ulam design "secret," the United States agreed to exchange some of its nuclear designs with the United Kingdom, which led to the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement.

China

The People's Republic of China detonated its first device using a Teller–Ulam design June 1967 ("Test No. 6"), a mere 32 months after detonating its first fission weapon (the shortest fission-to-fusion development yet known), with a yield of 3.3 Mt. Little is known about the Chinese thermonuclear program.

Development of the bomb was led by Yu Min.[18]

France

Very little is known about the French development of the Teller–Ulam design beyond the fact that it detonated a 2.6 Mt device in the "Canopus" test in August 1968.

India

On 11 May 1998, India announced that it has detonated a hydrogen bomb in its Operation Shakti tests ("Shakti I", specifically).[19] Some non-Indian analysts, using seismographic readings, have suggested that it might not be the case by pointing at the low yield of the test, which they say is close to 30 kilotons (as opposed to 45 kilotons announced by India).[20]

However, some non-Indian experts agree with India. Dr. Harold M. Agnew, former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, said that India's assertion of having detonated a staged thermonuclear bomb was believable.[21] The British seismologist Roger Clarke argued that seismic magnitudes suggested a combined yield of up to 60 kilotonnes, consistent with the Indian announced total yield of 56 kilotonnes.[22] Professor Jack Evernden, a US seismologist, has always maintained that for correct estimation of yields, one should "account properly for geological and seismological differences between test sites." His estimation of the yields of the Indian tests concur with those of India.[23]

Indian scientists have argued that some international estimations of the yields of India's nuclear tests are unscientific.[23][24]

India says that the yield of its tests were deliberately kept low to avoid civilian damage and that it can build staged thermonuclear weapons of various yields up to around 200 kilotons on the basis of those tests.[23] Another cited reason for the low yields was that radioactivity released from yields significantly more than 45 kilotons might not have been contained fully.[23]

Even low-yield tests can have a bearing on thermonuclear capability, as they can provide information on the behavior of primaries without the full ignition of secondaries.[25]

North Korea

North Korea claimed to have tested its miniaturised thermonuclear bomb on January 6, 2016. North Korea's first three nuclear tests (2006, 2009 and 2013) had a relatively low yield and do not appear to have been of a thermonuclear weapon design. In 2013, the South Korean Defense Ministry had speculated that North Korea might be trying to develop a "hydrogen bomb" and such a device might be North Korea's next weapons test.[26][27] In January 2016, North Korea claimed to have successfully tested a hydrogen bomb,[28] but only a magnitude 5.1 seismic event was detected at the time of the test,[29] a similar magnitude to the 2013 test of a 6–9 kt atomic bomb. Those seismic recordings have scientists worldwide doubting North Korea's claim that a hydrogen bomb was tested and suggest it was a non-fusion nuclear test.[30] On September 9, 2016, North Korea conducted their fifth nuclear test which yielded between 10 and 30 kilotons.[31][32][33]

On September 3, 2017, North Korea conducted a sixth nuclear test just a few hours after photographs of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un inspecting a device resembling a thermonuclear weapon warhead were released.[34] Initial estimates in first few days were between 70 and 160 kilotons[35][36][37][38][39] and were raised over a week later to range of 250 to over 300 kilotons.[40][41][42][43] Jane's Information Group estimated, based mainly on visual analysis of propaganda pictures, that the bomb might weigh between 250 and 360 kg (550 and 790 lb).[44]

Public knowledge

The Teller–Ulam design was for many years considered one of the top nuclear secrets, and even today, it is not discussed in any detail by official publications with origins "behind the fence" of classification. The policy of the US Department of Energy (DOE) has always been not to acknowledge when "leaks" occur since doing such would acknowledge the accuracy of the supposed leaked information. Aside from images of the warhead casing but never of the "physics package" itself, most information in the public domain about the design is relegated to a few terse statements and the work of a few individual investigators.

Here is a short discussion of the events that led to the formation of the "public" models of the Teller–Ulam design, with some discussions as to their differences and disagreements with those principles outlined above.

Early knowledge

The general principles of the "classical Super" design were public knowledge even before thermonuclear weapons were first tested. After Truman ordered the crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in January 1950, the Boston Daily Globe published a cutaway description of a hypothetical hydrogen bomb with the caption Artist's conception of how H-bomb might work using atomic bomb as a mere "trigger" to generate enough heat to set up the H-bomb's "thermonuclear fusion" process.[45]

The fact that a large proportion of the yield of a thermonuclear device stems from the fission of a uranium 238 tamper (fission-fusion-fission principle) was revealed when the Castle Bravo test "ran away," producing a much higher yield than originally estimated and creating large amounts of nuclear fallout.[13]

DOE statements

In 1972, the DOE declassified a statement that "The fact that in thermonuclear (TN) weapons, a fission 'primary' is used to trigger a TN reaction in thermonuclear fuel referred to as a 'secondary'", and in 1979, it added: "The fact that, in thermonuclear weapons, radiation from a fission explosive can be contained and used to transfer energy to compress and ignite a physically separate component containing thermonuclear fuel." To the latter sentence, it specified, "Any elaboration of this statement will be classified." (emphasis in original) The only statement that may pertain to the sparkplug was declassified in 1991: "Fact that fissile and/or fissionable materials are present in some secondaries, material unidentified, location unspecified, use unspecified, and weapons undesignated." In 1998, the DOE declassified the statement that "The fact that materials may be present in channels and the term 'channel filler,' with no elaboration," which may refer to the polystyrene foam (or an analogous substance). (DOE 2001, sect. V.C.)[clarification needed]

Whether the statements vindicate some or all of the models presented above is up for interpretation, and official US government releases about the technical details of nuclear weapons have been purposely equivocating in the past (such as the Smyth Report). Other information, such as the types of fuel used in some of the early weapons, has been declassified, but precise technical information has not been.

The Progressive case

Most of the current ideas of the Teller–Ulam design[clarification needed] came into public awareness after the DOE attempted to censor a magazine article by the anti-weapons activist Howard Morland in 1979 on the "secret of the hydrogen bomb." In 1978, Morland had decided that discovering and exposing the "last remaining secret" would focus attention onto the arms race and allow citizens to feel empowered to question official statements on the importance of nuclear weapons and nuclear secrecy. Most of Morland's ideas about how the weapon worked were compiled from highly-accessible sources; the drawings that most inspired his approach came from the Encyclopedia Americana. Morland also interviewed, often informally, many former Los Alamos scientists (including Teller and Ulam, though neither gave him any useful information), and used a variety of interpersonal strategies to encourage informational responses from them (such as by asking questions such as "Do they still use sparkplugs?" even if he was unaware what the latter term specifically referred to). (Morland 1981)

Morland eventually concluded that the "secret" was that the primary and secondary were kept separate and that radiation pressure from the primary compressed the secondary before igniting it. When an early draft of the article, to be published in The Progressive magazine, was sent to the DOE after it had fallen into the hands of a professor who was opposed to Morland's goal, the DOE requested that the article not be published and pressed for a temporary injunction. After a short court hearing in which the DOE argued that Morland's information was (1). likely derived from classified sources, (2). if not derived from classified sources, itself counted as "secret" information under the "born secret" clause of the 1954 Atomic Energy Act, and (3). dangerous and would encourage nuclear proliferation, Morland and his lawyers disagreed on all points, but the injunction was granted, as the judge in the case thought that it was safer to grant the injunction and allow Morland, et al., to appeal,[citation needed] which they did in United States v. The Progressive, et al. (1979).

Through a variety of more complicated circumstances,[clarification needed] the DOE case began to wane, as it became clear that some of the data it attempted to claim as "secret" had been published in a students' encyclopedia a few years earlier. After another hydrogen bomb speculator, Chuck Hansen, had his own ideas about the "secret" (quite different from Morland's) published in a Wisconsin newspaper, the DOE claimed The Progressive case was moot, dropped its suit, and allowed the magazine to publish, which it did in November 1979. Morland had by then, however, changed his opinion of how the bomb worked to suggesting that a foam medium (the polystyrene) rather than radiation pressure was used to compress the secondary and that in the secondary was a sparkplug of fissile material as well. He published the changes, based in part on the proceedings of the appeals trial, as a short erratum in The Progressive a month later.[46] In 1981, Morland published a book, The secret that exploded, about his experience, describing in detail the train of thought which led him to his conclusions about the "secret."

Because the DOE sought to censor Morland's work, one of the few times that it violated its usual approach of not acknowledging "secret" material that had been released, it is interpreted as being at least partially correct, but to what degree it lacks information or has incorrect information is not known with any great confidence. The difficulty which a number of nations had in developing the Teller–Ulam design (even when they understood the design, such as with the United Kingdom) makes it somewhat unlikely that the simple information alone is what provides the ability to manufacture thermonuclear weapons.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the ideas put forward by Morland in 1979 have been the basis for all current speculation on the Teller–Ulam design.

See also

Notes

- ^ The term "heterocatalytic" was Teller and Ulam's jargon for their new idea; using an atomic explosion to ignite a secondary explosion in a mass of fuel located outside the initiating bomb.

References

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard (1 August 1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-68-480400-2. LCCN 95011070. OCLC 456652278. OL 7720934M. Wikidata Q105755363 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e Young, Ken; Schilling, Warner R. (15 February 2020). Super Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen Bomb (1st ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1501745164. OCLC 1164620354. OL 28729278M.

- ^ Galison, Peter; Bernstein, Barton J. (1 January 1989). "In Any Light: Scientists and the Decision to Build the Superbomb, 1952-1954". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 19 (2): 267–347. doi:10.2307/27757627. eISSN 1939-182X. ISSN 1939-1811. JSTOR 27757627.

- ^ Teller, Edward; Ulam, Stanislaw (March 9, 1951). On Heterocatalytic Detonations I. Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors (PDF) (Report). LAMS-1225. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2014 – via Nuclear Non-Proliferation Institute. This is the original classified paper by Teller and Ulam proposing staged implosion. This declassified version is heavily redacted, leaving only a few paragraphs.

- ^ Stix, Gary (20 October 1999). "Infamy and Honor at the Atomic Café: Father of the hydrogen bomb, "Star Wars" missile defense and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career". Scientific American. Vol. 281, no. 4. pp. 42–43. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ Bethe, Hans (1952). "Memorandum on the History of the Thermonuclear Program". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ Bethe, Hans (1954). "Testimony in the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer". Atomic Archive. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ^ * H.A. Bethe, " J. Robert Oppenheimer 1904–1967," National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Biographical Memoirs (1997, vol. 71, pp. 175–218; on 197)

- ^ Dyson, George (March 1, 2012). Turing's Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe. Penguin Books Limited. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-7181-9450-5.

- ^ Powers, Thomas. "An American Tragedy". The New York Review. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ "Edward Teller's Memoirs: a book review by S. Uchii", PHS Newsletter (Philosophy and History of Science, Kyoto University), no. 52, July 22, 2003

- ^ Schweber, Silvan S. (January 7, 2007). In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist. Princeton Series in Physics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691127859. OCLC 868971191. OL 7757230M – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Why the H-Bomb Is Now Called the 3-F". LIFE. December 5, 1955. pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Holloway, David (28 September 1994). Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939-1956 (1st ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300060560. OCLC 470165274. OL 1084400M.

- ^ De Geer, Lars-Erik (December 1, 1991). "The radioactive signature of the hydrogen bomb". Science & Global Security. 2 (4): 351–363. Bibcode:1991S&GS....2..351D. doi:10.1080/08929889108426372. ISSN 0892-9882.

- ^ Khariton, Yuli; Smirnov, Yuri; Rothstein, Linda; Leskov, Sergei (1 May 1993). "The Khariton Version". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 49 (4): 20–31. Bibcode:1993BuAtS..49d..20K. doi:10.1080/00963402.1993.11456341. eISSN 1938-3282. ISSN 0096-3402. LCCN 48034039. OCLC 470268256.

- ^ "The Tsar Bomba ("King of Bombs")". Retrieved October 10, 2010.

from fireball radius scaling laws, one would expect the fireball to reach down and engulf the ground ... In fact, the shock wave reaches the ground ... and bounces upward, striking the bottom of the fireball, ... preventing actual contact with the ground.

- ^ Li Jing (January 10, 2015). "Yu Min, 'father of China's H-bomb', wins top science award". South China Morning Post. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Burns, John F. (May 12, 1998). "India Sets 3 Nuclear Blasts, Defying a Worldwide Ban; Tests Bring a Sharp Outcry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ "What Are the Real Yields of India's Test?", Nuclear Weapon Archive, November 2001

- ^ Burns, John F. (May 18, 1998). "Nuclear Anxiety: The Overview; India Detonated a Hydrogen Bomb, Experts Confirm". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ "We have an adequate scientific database for designing ... a credible nuclear deterrent". frontline.thehindu.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Press Statement by Dr. Anil Kakodkar and Dr. R. Chidambaram on Pokhran-II tests". pib.nic.in. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ "Pokhran – II tests were fully successful; given India capability to build nuclear deterrence: Dr. Kakodkar and Dr. Chidambaram". pib.nic.in. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ "India's Nuclear Weapons Program: Operation Shakti, 1998, Nuclear Weapon Archive, March 2001

- ^ Kim Kyu-won (February 7, 2013). "North Korea could be developing a hydrogen bomb". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ Kang Seung-woo; Chung Min-uck (February 4, 2013). "North Korea may detonate H-bomb". Korea Times. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ "North Korea Claims It Successfully Tested Hydrogen Bomb". ABC News. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ M5.1 – 21km ENE of Sungjibaegam, North Korea (Report). USGS. January 6, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ "North Korea nuclear H-bomb claims met by scepticism". BBC News. January 6, 2016.

- ^ "South Korea says North's nuclear capability 'speeding up', calls for action". Reuters. September 9, 2016. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016.

- ^ "North Korea claims success in fifth nuclear test". BBC News. September 9, 2016.

- ^ "South Korea says North's nuclear capability 'speeding up', calls for action". Reuters. September 9, 2016. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Kim inspects 'nuclear warhead': A picture decoded". BBC News. September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Yonhap News Agency".

- ^ "Large nuclear test in North Korea on 3 September 2017 - NORSAR". Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "North Korea's 3 September 2017 Nuclear Test Location and Yield: Seismic Results from USTC". Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "North Korean nuke test put at 160 kilotons as Ishiba urges debate on deploying U.S. atomic bombs". The Japan Times. September 6, 2017. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017.

- ^ "US Intelligence: North Korea's Sixth Test Was a 140 Kiloton 'Advanced Nuclear' Device – The Diplomat".

- ^ "The nuclear explosion in North Korea on 3 September 2017: A revised magnitude assessment - NORSAR". Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "North Korea's Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site: Satellite Imagery Shows Post-Test Effects and New Activity in Alternate Tunnel Portal Areas - 38 North: Informed Analysis of North Korea". September 12, 2017.

- ^ "North Korea nuclear test may have been twice as strong as first thought - The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ^ "SAR Image of Punggye-ri".

- ^ "North Korea bargains with nuclear diplomacy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "Hail Truman H-Bomb Order". Boston Daily Globe: 1. February 1, 1950. – reprinted in Alex Wellerstein (June 18, 2012). "What If Truman Hadn't Ordered the H-bomb Crash Program?".

- ^ "The H-Bomb Secret: How we got it and why we're telling it" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. (3.48 MB) , The Progressive, vol. 43, no. 11, November 1979

Further reading

History

- Braun, Reiner; Hinde, Robert; Krieger, David; Kroto, Harold; Milne, Sally, eds. (17 July 2007). Joseph Rotblat: Visionary for Peace. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3527406906. LCCN 2007476036. OL 12767868M. Retrieved 9 February 2021 – via Google Books.

- Bundy, McGeorge (28 November 1988). Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years (1st ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-0394522784. LCCN 89040089. OCLC 610771749. OL 24963545M – via Internet Archive.

- DeGroot, Gerard J. (31 March 2005). The Bomb: A Life. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674017245. OCLC 57750742. OL 7671320M – via Internet Archive.

- Galison, Peter; Bernstein, Barton J. (1 January 1989). "In Any Light: Scientists and the Decision to Build the Superbomb, 1952-1954". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 19 (2): 267–347. doi:10.2307/27757627. eISSN 1939-182X. ISSN 1939-1811. JSTOR 27757627.

- Goncharov, German A. (31 October 1996). "American and Soviet H-bomb development programmes: historical background". Physics-Uspekhi. 39 (10): 1033–1044. Bibcode:1996PhyU...39.1033G. doi:10.1070/PU1996v039n10ABEH000174. eISSN 1468-4780. ISSN 1063-7869. LCCN 93646146. OCLC 36334507. S2CID 250861572.

- Holloway, David (28 September 1994). Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939-1956 (1st ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300060560. OCLC 470165274. OL 1084400M.

- Rhodes, Richard (1 August 1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-68-480400-2. LCCN 95011070. OCLC 456652278. OL 7720934M. Wikidata Q105755363 – via Internet Archive.

- Schweber, Silvan S. (January 7, 2007). In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist. Princeton Series in Physics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691127859. OCLC 868971191. OL 7757230M – via Internet Archive.

- Stix, Gary (20 October 1999). "Infamy and Honor at the Atomic Café: Father of the hydrogen bomb, "Star Wars" missile defense and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career". Scientific American. Vol. 281, no. 4. pp. 42–43. ISSN 0036-8733.

- Young, Ken; Schilling, Warner R. (15 February 2020). Super Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen Bomb (1st ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1501745164. OCLC 1164620354. OL 28729278M.

- Younger, Stephen M. (6 January 2009). The Bomb: A New History (1st ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0061537196. OCLC 310470696. OL 24318509M – via Internet Archive.

Analyzing fallout

- De Geer, Lars-Erik (1991). "The radioactive signature of the hydrogen bomb". Science & Global Security. 2 (4): 351–363. Bibcode:1991S&GS....2..351D. doi:10.1080/08929889108426372. ISSN 0892-9882. OCLC 15307789.

- Khariton, Yuli; Smirnov, Yuri; Rothstein, Linda; Leskov, Sergei (1 May 1993). "The Khariton Version". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 49 (4): 20–31. Bibcode:1993BuAtS..49d..20K. doi:10.1080/00963402.1993.11456341. eISSN 1938-3282. ISSN 0096-3402. LCCN 48034039. OCLC 470268256.

The Progressive Case

- De Volpi, Alexander; Marsh, Gerald E.; Postol, Ted; Stanford, George (1 May 1981). Born Secret: The H-Bomb, the Progressive Case and National Security (1st ed.). Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0080259956. OCLC 558172005. OL 7311029M – via Internet Archive.

- Morland, Howard (1 May 1981). The secret that exploded. Random House. ISBN 0394512979. LCCN 80006032. OCLC 7196781. OL 4094494M.

External links

- PBS: Race for the Superbomb: Interviews and Transcripts Archived March 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (with U.S. and USSR bomb designers as well as historians).

- Howard Morland on how he discovered the "H-bomb secret" (includes many slides).

- The Progressive November 1979 issue – "The H-Bomb Secret: How we got it, why we're telling" (entire issue online).