Q*bert

| Q*bert | |

|---|---|

| File:Q-bert Poster.png An advertisement flyer for Q*bert, which depicts the arcade cabinet, the orange title character, the purple snake enemy Coily, and the green enemy Slick. | |

| Developer(s) | Gottlieb |

| Publisher(s) | Gottlieb Parker Brothers Ultra Games Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Designer(s) | Warren Davis and Jeff Lee |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari 8-bit family, ColecoVision, Commodore 64, Commodore VIC-20, Intellivision, NES, Philips Videopac, Mobile, Othello Multivision, Standalone tabletop, Texas Instruments TI-99/4A |

| Release | Arcade: Fall 1982 (NA) Atari 2600: 1983 (NA) |

| Genre(s) | Action / Puzzle |

| Mode(s) | Up to 2 players, alternating turns |

Q*bert /ˈkjuːbərt/ is an arcade video game developed and published by Gottlieb in 1982. It is an isometric action game that features two-dimensional (2D) graphics. The object is to change the color of every cube in a pyramid by making the on-screen character jump on top of the cube while avoiding obstacles and enemies. Players use a joystick to control the character.

The game was conceived by Warren Davis and Jeff Lee. Lee designed the title character based on childhood influences and gave Q*bert a large nose that shoots projectiles. His original idea involved traversing a pyramid to shoot enemies, but Davis removed the shooting game mechanic to simplify gameplay. Q*bert was developed under the project name Cubes, but was briefly named Snots And Boogers and @!#?@! during development. The character Q*bert became known for his "swearing", an incoherent phrase of synthesized speech generated by the sound chip and a speech balloon of nonsensical characters that appear when he is hit.

Q*bert was well received in arcades and by critics, who praised the graphics, gameplay and main character. The success resulted in sequels and use of the character's likeness in merchandising, such as appearances on lunch boxes, toys, and an animated television show. The game has since been ported to numerous platforms.

Because the game was developed during the period when Columbia Pictures owned Gottlieb, the intellectual rights to Q*bert stayed with Columbia even after they divested themselves of Gottlieb's assets in 1984. Therefore, it is currently a property of Sony Pictures Entertainment who acquired Columbia in 1989. The Q*bert character's appearance in the 2012 movie Wreck-It Ralph is credited to "Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc."

Gameplay

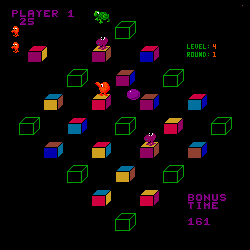

Q*bert is an action game with puzzle elements played from an isometric third-person perspective. The game is played using a single, diagonally mounted four-way joystick.[1] The player controls Q*bert, who starts each game at the top of a pyramid made of 28 cubes, and moves by hopping diagonally from cube to cube. Landing on a cube causes it to change color, and changing every cube to the target color allows the player to progress to the next stage.[2]

At first, jumping on every cube once is enough to advance. In later stages, each cube must be hit twice to reach the target color. Other times, cubes change color every time Q*bert lands on them, instead of remaining on the target color once they reach it. Both elements are then combined in subsequent stages. Jumping off the pyramid results in the character's death.[3]

The player is impeded by several enemies, introduced gradually to the game:

- Coily - Coily first appears as a purple egg that bounces to the bottom of the pyramid and then transforms into snake that chases after Q*bert.[1]

- Ugg and Wrongway - Two purple creatures that hop along the sides of the cubes. They keep moving in one direction and fall off the pyramid when they reach the end.[1]

- Slick and Sam - Two green creatures that descend down the pyramid and revert cubes whose color has already been changed.[3]

A collision with purple enemies is fatal to the character, whereas the green enemies are removed from the board upon contact.[1] Colored balls occasionally appear at the second row of cubes and bounce downward; contact with a red ball is lethal to Q*bert, while contact with a green one immobilizes the on-screen enemies for a limited time.[3] A multi-colored disc on either side of the pyramid serves as an escape device from danger, particularly Coily. When Q*bert jumps on a disc, it transports him to the top of the pyramid. If Coily is in close pursuit of the character, he is hereby tricked into jumping off the pyramid.[1] This causes all enemies and balls on the screen to disappear.

Points are awarded for each color change (25), defeating coily with a flying disc (500), remaining discs at the end of a stage (at higher stages, 50 or 100) and catching green balls (100) or Slick and Sam (300 each).[3] Extra lives are granted for reaching certain scores, which are set by the machine operator.[4]

Development

Concept

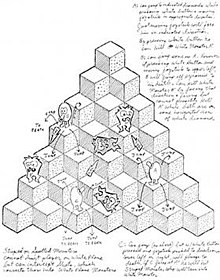

The basic ideas for the game were thought up by Warren Davis and Jeff Lee. The initial concept began when artist Jeff Lee drew a pyramid of cubes inspired by M. C. Escher.[5] Lee felt a game could be derived from the artwork, and created an orange, armless main character. The character jumped along the cubes and shot projectiles from a tubular nose at enemies.[5] Enemies included a blue creature, later changed purple and named Wrong Way, and an orange creature, later changed green and named Sam.[6] Lee had drawn similar characters since childhood, inspired by characters from comics, cartoons, Mad magazine and by artist Ed "Big Daddy" Roth.[7] Q*bert's design later included a speech balloon with a string of nonsensical characters, "@!#?@!",[Note 1] which Lee originally presented as joke.[6]

Implementation

Warren Davis, a programmer hired to work on the action game Protector,[5] noticed Lee's ideas, and asked if he could use them to practice programming randomness and gravity as game mechanic. Thus, he added balls that bounced from the pyramid's top to bottom.[6] Because Davis was still learning how to program game mechanics, he wanted to keep the design simple. He also felt games with complex control schemes were frustrating and wanted something that could be played with one hand. To accomplish this, Davis removed the shooting and changed the objective to saving the protagonist from danger.[7] As Davis worked on the game one night, Gottlieb's vice president of engineering, Ron Waxman, noticed him and suggested to change the color of the cubes after the game's character has landed on them.[5][6][7] Davis implemented a unique control scheme; a four-way joystick was rotated 45° to match the directions of Q*bert's jumping. Staff members at Gottlieb urged for a more conventional orientation, but Davis stuck to his decision.[5][6]

The game features amplified monaural sound and pixel graphics on a 19 inch CRT monitor. It uses an Intel 8086 central processing unit that operates at 5MHz.[8]

Audio

We wanted the game to say, 'You have gotten 10,000 bonus points', and the closest I came to it after an entire day would be "bogus points". Being very frustrated with this, I said, "Well, screw it. What if I just stick random numbers in the chip instead of all this highly authored stuff, what happens?"

A MOS Technology 6502 chip that operates at 894 kHz generates the sound effects, and a speech synthesizer by Votrax generates Q*bert's incoherent expressions.[8] The audio system uses 128B of random-access memory and 4KB of erasable programmable read only memory to store the sound data and code to implement it. Like other Gottlieb games, the sound system was thoroughly tested to ensure it would handle daily usage. In retrospect, audio engineer David Thiel commented that such testing minimized time available for creative designing.[9]

Thiel was tasked with using the synthesizer to produce English phrases for the game. However, he was unable to create coherent phrases and eventually chose to string together random phonemes instead. Thiel also felt the incoherent speech was a good fit for the "@!#?@!" in Q*bert's speech balloon. Following a suggestion from technician Rick Tighe, a pinball machine component was included to make a loud sound when a character falls off the pyramid.[5][6] The sound is generated by an internal coil that hits the interior of a cabinet wall. Foam padding was added to the area of contact on the cabinet; the developers felt the softer sound better matched a fall rather than a loud knocking sound. The cost of installing foam, however, was too expensive and the padding was omitted.[7]

Title

The Gottlieb staff had difficulty naming the game. Aside from the project name "Cubes", it was untitled for most of the development process. The staff agreed the game should be named after the main character, but disagreed on the name.[6] Lee's title for the initial concept—Snots And Boogers—was rejected, as was a list of suggestions compiled from company employees.[10][6] According to Davis, vice president of marketing Howie Rubin championed @!#?@! as the title. Although staff members argued it was silly and would be impossible to pronounce, a few early test models were produced with @!#?@! as the title on the units' artwork.[10][6] During a meeting, "Hubert" was suggested, and a staff member thought of combining "Cubes" and "Hubert" into "Cubert".[10][6] Art director Richard Tracy changed the name to "Q-bert", and the dash was later changed to an asterisk. In retrospect, Davis expressed regret for the asterisk, because he felt it prevented the name from becoming a common crossword term and it is a wildcard character for search engines.[6]

Testing

As development neared the production stage, Q*bert underwent location tests in local arcades under its preliminary title @!#?@!, before being widely distributed. According to Jeff Lee, his oldest written record attesting to the game being playable as @!#?@! in a public location, a Brunswick bowling alley, dates back to September 11, 1982.[6] Gottlieb also conducted focus groups, in which the designers observed players through a two-way mirror.[6] The control scheme received a mixed reaction during play testing; some players adapted quickly while others found it frustrating.[6][7] Initially, Davis was worried players would not adjust to the different controls; some players would unintentionally jump off the pyramid several times, reaching a game over in about ten seconds. Players, however, became accustomed to the controls after playing several rounds of the game.[6] The different responses to the controls prompted Davis to reduce the game's level of difficulty—a decision that he would later regret.[7]

Release

A copyright claim registered with the United States Copyright Office by Gottlieb on February 10, 1983 cites the date of publication of Q*bert as October 18, 1982.[11] Video Games reported that the game was sold directly to arcade operators at its public showing at the AMOA show held November 18–20, 1982.[12] Q*bert is Gottlieb's fourth video game.[13]

Reception

Q*bert was Gottlieb's only video game that gathered huge critical and commercial success, selling around 25,000 arcade cabinets.[5] Cabaret and cocktail versions of the game were later produced. The machines have since become collector's items; the rarest of them are the cocktail versions.[14]

When the game was first introduced to a wider industry audience at the November 1982 AMOA show, it was immediately received favorably by the press. Video Games placed Q*bert first in its list of Top Ten Hits, describing it as "the most unusual and exciting game of the show" and stating that "no operator dared to walk away without buying at least one".[12] The Coin Slot reported "Gottlieb's game, Q*BERT, was one of the stars of the show", and predicted that "The game should do very well."[15]

Contemporaneous reviews were equally enthusiastic, and focused on the uniqueness of the gameplay and audiovisual presentation. Roger C. Sharpe of Electronic Games considered it "a potential Arcade Award winner for coin-op game of the year", praising innovative gameplay and outstanding graphics.[2] William Brohaugh of Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games described the game as an "all-round winner" that had many strong points. He praised the variety of sound effects and the graphics, calling the colors vibrant. Brohaugh lauded Q*bert's inventiveness and appeal, stating that the objective was interesting and unique.[13] Michael Blanchet of Electronic Fun suggested the game might push Pac-Man out of the spotlight in 1983. [1] Neil Tesser of Video Games also likened Q*bert to Japanese games like Pac-Man and Donkey Kong, due to the focus on characters, animation and story lines, as well as the "absence of violence".[16] Computer and Video Games magazine praised the game's graphics and colors.[4]

Electronic Games awarded Q*bert "Most Innovative Coin-op Game" of the year.[17] Video Game Player called it the "Funniest Game of the Year" among arcade games in 1983.[18]

Q*bert continues to be widely recognized as a significant part of video game history. Author Steven Kent and GameSpy's William Cassidy considered Q*bert one of the more memorable games of its time.[19][20] Author David Ellis echoed similar statements, calling it a "classic favorite".[21] 1UP.com's Jeremy Parish included Q*bert among the higher-profile classic games.[22] In 2008, Guinness World Records ranked it behind 16 other arcade games in terms of their technical, creative and cultural impact.[23]

Kim Wild of Retro Gamer magazine described the game as difficult yet addictive.[6] Author John Sellers also called Q*bert addictive, and praised the sound effects and three-dimensional appearance of the graphics.[10] Cassidy called the game unique and challenging; he attributed the challenge in part to the control scheme.[20] IGN's Jeremy Dunham felt the controls were poorly designed, describing them as "unresponsive" and "a struggle". He commented that despite the controls, the game is addictive.[24]

The main character also received positive press coverage. Edge magazine attributed the success of the game to the title character. They stated that players could easily relate to Q*bert, particularly because he swore.[7] Computer and Video Games, however, considered the swearing a negative, but still felt the character was appealing.[4] Cassidy believed the game's appeal lay in the main character. He described Q*bert as cute and having a personality that made him stand out in comparison to other popular video game characters.[20] The authors of High Score! referred to Q*bert as "ultra-endearing alien hopmeister", and the cutest game character of 1982.[25]

Ports

At the 1982 AMOA Show, Parker Brothers secured the license to publish home conversions of the Q*bert arcade game.[26] Parker first published a port to the Atari 2600,[27] and by the end of 1983, the company also advertised versions for Atari 5200, Intellivision, ColecoVision, the Atari 8-bit computer family, Commodore VIC-20, Texas Instruments TI-99/4A and Commodore 64.[28] The release of the Commodore 64 version was noted to lack behind the others[27] but appeared in 1984.[29] Parker Brothers also translated the game into a stand-alone tabletop electronic game.[30] It uses a VFD screen, and has since become a rare collector's item.[31] Q*bert was also published by Parker Brothers for the Philips Videopac in Europe,[32] by Tsukuda Original for the Othello Multivision in Japan,[33] and by Ultra Games for the NES in North America.[34]

The initial home port for the Atari 2600 was met with mixed reactions. Video Games warned that buyers of the Atari 2600 version "may find themselves just a little disappointed." They criticized the lack of music, the removing of the characters Ugg and Wrongway, and the system's troubles to handle the character sprites on screen at a steady performance.[35] Later Mark Brownstein of the same magazine was more in favor of the game, but still cited the presence of fewer cubes in the game's pyramidal layout and "pretty poor control" as negatives.[27] Will Richardson of Electronic Games noted a lack in audiovisual qualities and counter-intuitive controls, but commended the gameplay, stating that the game "comes much closer to its source of inspiration than a surface evaluation indicates".[36] Randi Hacker of Electronic Fun with Computers & Games called it a "sterling adaption [sic]"[37] In 2008, however, IGN's Levi Buchanan rated it the fourth worst Atari 2600 arcade port, citing poor visuals and a technical problem that makes the game excessively difficult; a lack of animations for enemies while jumping between cubes make it impossible to know which direction they travel until they land.[38]

Other home versions were well-received for the most part, with some exceptions. Of the ColecoVision version, Electronic Fun with Computers & Games noted that "Q*bert aficionados will not be disappointed".[39] Marc Brownstein of Video Games called it one of the best of the authorized versions.[27] Warren Davis also considered the ColecoVision version the most accurate port of the arcade.[6] Mark Brownstein judged the Atari 5200 version inferior to the ColecoVision, due to the imprecision of the Atari 5200 controller, but noted that "it does tend to grow on you."[27] Video Games determined the Intellivision as having the worst of the available ports, criticizing the system's controller for being inadequate for the game.[40] Antic magazine's David Duberman called the Atari 8-bit version "one of the finest translations of an arcade game for the home computer format."[41] Arthur Leyenberger of Creative Computing listed it as a runner-up for Best Arcade Adaptation to the system, praising its faithful graphics, sound, movement and playability.[42] Computer Games called the C64 version an "absolutely terrific translation" that "almost totally duplicates the arcade game," aside from its lack of synthesized speech.[29] The stand-alone tabletop was awarded Stand-Alone Game of the Year in Electronic games.[17]

In 2003, a version for Java-based mobile phones was announced by Sony Pictures Mobile.[43] Reviewers generally acknowledged it as a faithful port of the arcade original, but criticized the controls. Modojo's Robert Falcon stated that the diagonal controls take time to adapt to on a cell phone with traditional directions.[44] Michael French of Pocket Gamer concluded: "You can't escape the fact it doesn't exactly fit on mobile. The graphics certainly do, and the spruced-up sound effects are timeless… but really, it's a little too perfect a conversion."[45] Airgamer criticized the gameplay as monotonous and the difficulty as frustrating.[46] By contrast, Wireless Gaming Review called it "one of the best of mobile's retro roundup".[47]

On February 22, 2007, Q*bert was released on the PlayStation 3's PlayStation Network.[48] It features upscaled and filtered graphics,[22] an online leaderboard for players to post high-scores, and Sixaxis motion controls.[24] The game received a mixed reception. Dunham and Gerstmann did not enjoy the motion controls and felt it was a title only for nostalgic players.[24][49] Eurogamer.net's Richard Leadbetter judged the game's elements "too simplistic and repetitive to make them worthwhile in 2007".[50] In contrast, Parish considered the title worth purchasing, citing its addictive gameplay.[22]

Legacy

Market impact

Q*bert became one of the most merchandised arcade games behind Pac-Man,[6] although according to John Sellers it was not nearly as successful as that franchise or Donkey Kong.[10] The character's likeness appears on various items including coloring books, sleeping bags, frisbees, board games, wind-up toys, and stuffed animals.[10][6][20] However, the North American video game crash of 1983 depressed the market, and the game's popularity began to decline by 1984.[6][20]

In the years following its release, Q*bert has inspired many other games with similar concepts. The magazines Video Games and Computer Games both commented on the trend with features about Q*bert-like games in 1984. They listed Mr. Cool by Sierra On-Line, Frostbite by Activision, Q-Bopper by Accelerated Software, Juice by Tronix, Quick Step by Imagic, Flip & Flop and Boing by First Star Software, Pharaoh's Pyramid by Master Control Software, Pogo Joe by Screenplay, Rabbit Transit by Starpath, as games which had been inspired by Q*bert.[27][51] Further titles that have been identified as Q*bert-like games include J-bird by Orion Software,[52] Cubit by Micromax,[53] and in the UK Pogo by Ocean,[54] Spellbound by Beyond[55] and Hubert by Blaby Computer Games.[56]

Other media appearances

In 1983, Q*bert was adapted into an animated cartoon as part of CBS's Saturday Supercade, which features segments based on video game characters from the golden age of video arcade games. Saturday Supercade was produced by Ruby-Spears Productions, the Q*bert segments between 1983–1984.[57] The show is set in a United States, 1950s era town called "Q-Burg",[58] and stars Q*bert as a high school student, altered to include arms and hands.[20] He also has the ability to shoot black projectiles from his nose. Characters frequently say puns that add the letter "Q" to words.[58] Aside from Q*bert and the known game villains, the cartoon also includes new characters similar to Q*bert in appearance and naming.[59]

Q*bert, Coily, Ugg, Slick, and Sam appear in the 2012 Disney animated film Wreck-It Ralph.[60] They start out as "homeless" video game characters living in Game Central Station after their game was unplugged and taken out of Litwak's Arcade. Ralph gives them a cherry from Pac-Man as a gesture of kindness. After Ralph takes Markowski's uniform in Tapper's, he accidentally trips over Q*bert on his way to Hero's Duty. This leads Q*bert to go to Fix-It Felix Jr. to warn Felix that Ralph has "gone Turbo." In that scene, Felix apparently speaks "Q*bert-ese." At the end of the film, Ralph and Felix decide to let Q*bert, Coily, Ugg, Slick, Sam, and the generic homeless video game characters into Fix-It Felix Jr., suggesting that they help out in the bonus levels where Coily, Ugg, Slick, Sam, and the generic video game characters assist Ralph in wrecking the building while Q*bert assists Felix in fixing it.[61]

Pop culture references

The 1993 IBM PC role-playing game Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds features a segment where the player has to solve a pyramid puzzle as an homage to Q*bert.[62]

More recently, the game or its characters have been referenced in several animated television series. In the Family Guy episode "Chick Cancer", Stewie reflects on how it was easier being Q*bert's room mate and an animation of him on the game board is shown.[63] In "Anthology of Interest II" of Futurama, he is one of the aliens that attack to invade earth in a segment of video game parodies.[64] In The Simpsons episode "In the Name of the Grandfather" Marge, Bart and Lisa hop around the stones of the Giants Causeway in a game of Q*bert.[65][66] The Robot Chicken episode "Sushi Rolls" is in general a Street Fighter parody, but in the end M. Bison is shown inside the game Q*bert.[67] In Mad: "James Bond: Reply All", Q*bert is seen at the MI6 lab.[68] Q*bert also appeared on the battlefield in South Park: "Imaginationland: Episode III".[69]

High score records

On November 28, 1983, Rob Gerhardt reached a record score of 33,273,520 points in a Q*bert marathon.[70] He held it for almost 30 years, until George Leutz from Brooklyn, NY played one game of Q*bert for eighty-four hours and forty-eight minutes on February 14–18, 2013 at Richie Knucklez' Arcade in Flemington, NJ.[71] He scored 37,163,080 points.[72] Doris Self, credited by Guinness World Records as the "oldest competitive female gamer",[73] set the tournament record score of 1,112,300 for Q*bert in 1984 at the age of 58. Her record was surpassed by Drew Goins on June 27, 1987 with a score of 2,222,220.[74] Self continuously attempted to regain the record until her death in 2006.[6]

Creators Davis and Lee expressed pride at the longevity of the game's memory; Davis also said he was surprised people still positively remember the game.[6] In describing Q*bert's legacy, Jeff Gerstmann of GameSpot referred to the game as a "rare arcade success".[49] Despite its success, the two creators did not receive royalties as Gottlieb had no such program in place at the time.[6]

Updates, remakes and sequels

Faster Harder More Challenging Q*bert

Believing that the original game was too easy, Davis initiated development of Faster Harder More Challenging Q*bert (also known as FHMC Q*bert) in 1983,[7] which increases the difficulty, introduces a new enemy named Q*bertha and adds a bonus round.[75] The project, however, was canceled and the game never entered production.[6] Davis later released FHMC Q*bert's ROM image onto the web[6].

Q*bert's Quest

Gottlieb also released a pinball game, Q*bert's Quest, based on the arcade version. It features two pairs of flippers in an "X" formation and audio from the arcade.[6][76] Gottlieb produced fewer than 900 units.[76]

Q*bert's Qubes

Several video game sequels were released over the years, but did not reach the same level of success as the original.[6][20] The first, titled Q*bert's Qubes, shows a copyright of 1983 on its title screen.[10][77] It was manufactured by Mylstar Electronics,[Note 2] and uses the same hardware as the original.[77] The game features Q*bert, but introduces new enemies: Meltniks, Soobops, and Rat-A-Tat-Tat.[78][79] The player navigates the protagonist around a plane of cubes while avoiding enemies. Jumping on a cube causes it to rotate, changing the color of the visible sides of the cube.[77][78] The goal is to match the cubes in a row; later levels require multiple rows to match.[79] Despite the popularity of the franchise, the game's release was hardly noticed.[10] Parker Brothers showcased home versions of Q*bert's Qubes at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in January 1985.[80] Q*bert's Qubes was ported to the Colecovision and Atari 2600.[78][81][82]

Q*bert (1986)

Konami, who had distributed Q*bert to Japanese arcades in 1983,[83], produced a game with the title Q*bert for MSX computers in 1986, released in Japan and Europe. However, the main character is a little dragon, and the mechanics are based on Q*bert's Qubes. The player once again turns around colored cubes by jumping from cube to cube, trying to reach the displayed target pattern. Contrary to Mylstar's arcade game, each of the 50 stages has a different pattern of cubes, in addition to the known rule extensions in later stages. The game also features a competetive 2-player mode, where each side is assigned a different pattern, and the players can score points either by completing their pattern first, or by pushing the other off the board. [84]

Q*bert for Game Boy

In 1992, this handheld game was developed by Realtime Associates and published by Jaleco in 1992. It features 64 boards in different shapes.[85]

Q*bert 3

Q*bert 3 for the SNES was also developed by Realtime Associates and released in 1992.[86] Jeff Lee, creator of the Q*bert character, also worked on the graphics for this game.[87] Q*bert 3 features gameplay similar to the original, but like the Game Boy game, it has larger levels of varying shapes. In addition to enemies from the first game, it introduces several new enemies (Frogg, Top Hat, and Derby).[88][89]

Q*bert (1999)

A remake with three-dimensional (3D) graphics was released by Hasbro Interactive on the PlayStation in 1999 and on the Dreamcast the following year. It features three modes of play: classic, adventure, and competitive multiplayer.[90][91] Allgame's Brett Weiss praised all aspects of the game,[90] while Parish called it a poor adaptation.[22] Kevin Rice of Next Generation Magazine praised the game's graphics, but criticized the new level designs. He further commented that adventure mode was not enjoyable.[91]

Q*bert 2004

In 2004, Sony Pictures released a Flash-based remake titled Q*bert 2004, containing a faithful rendition of the original arcade game, and 50 levels with new board layouts and six new visual themes.[92] Q*Bert Deluxe for iOS devices was initially released as a rendition of the arcade game, but later received updates with the themes and stages from Q*Bert 2004.[93]

Q*bert 2005

In 2005, Sony Pictures released Q*bert 2005 as a download for Windows[94] and as a Flash browser applet,[citation needed] featuring 50 different levels.[94]

Q*bert Rebooted

On July 2, 2014 Gonzo Games and Sideline amusement announced Q*bert Rebooted to be released on Steam, iOS and Android. The title is going to contain the classic arcade game alongside a new playing mode using hexagonal shapes.[95]

Notes

- ^ The original artwork displays the first and fifth character as spirals. The at sign ("@") is used in its place in the text of the references.

- ^ The Coca-Cola Company acquired Columbia Pictures, Gottlieb's owner, in 1982, and transferred assets to a new subsidiary, Mylstar Electronics, in 1983.

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Cursing Q*Bert: @!#?@! you, Coily!". Electronic Fun with Computers & Games (Volume 1, Number 5). Fun & Games Publishing: 92. March 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Sharpe, Roger C. (May 1983). "Is This the Next Arkie Winner?". Electronic Games (Volume 1, Number 15). Reese Publishing Company: 78–79.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d "Arcade Action Close-Up: Crazy For Q&bert's Cube". Vidiot. Creem Publications: 30–31. April/May 1983.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "'Q' Up for this One". Computer and Video Games (18). EMAP: 31. April 1983.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 222–224. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Wild, Kim (September 2008). "The Making of Q*bert". Retro Gamer (54). Imagine Publishing: 70–73.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Edge Staff (January 2003). "The Making of Q*bert". Edge (132): 114–117. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ^ a b "Q*bert Videogame by Gottlieb (1982)". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Greenebaum, Ken; Barzel, Ronen, eds. (2004). "Retro Game Sound: What We Can Learn from 1980s Era Synthesis". Audio Anecdotes: Tools, Tips, and Techniques for Digital Audio, Volume 1. A K Peters, Ltd. pp. 164–165. ISBN 1-56881-104-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Sellers, John (August 2001). Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games. Running Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 0-7624-0937-1.

- ^ Q-bert (Registration Number PA0000164088), The Library of Congress, 1983-02-10, retrieved 2014-04-22

- ^ a b "Top Ten Hits". Video Games (Volume 1, Number 7). Pumpkin Press: 66. March 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Brohaugh, William (Fall 1983). "Q*bert: A Player's Guide". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. 1 (2): 28.

- ^ Ellis, David (2004). "Arcade Classics". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 402. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- ^ Pugliese, Mike (January 1983). "The Amoa Show". The Coin Slot (Volume 8, Number 4). Rosanna B. Harris: 27–29.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "Top Ten Hits". Video Games (Volume 1, Number 8). Pumpkin Press: 26–30. March 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "1984 Arcade Awards". Electronic Games (Volume 2, Number 11). Reese Communications: 68–81. January 1984.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "1983 Golden Joystick Awards". Electronic Games (Volume 2, Number 11). Reese Communications: 49–51. August–September 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Kent, Steven (2001). "The Golden Age (Part 2: 1981–1983)". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cassidy, William (2002-06-23). "Hall of Fame: Q*bert". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ellis, David (2004). "A Brief History of Video Games". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 7. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- ^ a b c d Parish, Jeremy (2007-02-26). "Retro Roundup 2/26: Ocarina of Time, Q*Bert, Chew Man Fu". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008-03-11). "Top 100 Arcade Games: Top 20–6". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ a b c Dunham, Jeremy (2007-02-23). "Q*Bert Review". IGN. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ "Q*Bert". High Score! the illustrated history of electronic games (second ed.). McGraw-Hill/Osborne. 2004. p. 84. ISBN 0-07-223172-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Parker Grabs Two Hot Licenses". Electronic Games (Volume 1, Number 14). Reese Publishing Company: 8. April 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e f Brownstein, Mark (March 1984). "Follow the Leader: Spin-offs Jump To The Q*bert Challenge". Video Games (Volume 2, Number 6). Pumpkin Press: 28–31.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "How to Get Q*bert Out of your System". Electronic Games (Volume 2, Number 10). Reese Communications: 101. December 1983.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Q*Bert". Computer Games (Volume 3, Number 2). Carnegie Publications: 60. June 1984.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Worley, Joyce (January 1984). "The Block Bouncer Busts Loose!". Electronic Games (Volume 2, Number 11). Reese Communications: 122–125.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Ellis, David (2004). "Classics Handheld and Tabletop Games". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. p. 237. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- ^ "Parker Video Game Cartridge: Q*bert". RetroMO. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Q*bert". SMS Power!. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Q*bert for NES". MobyGames. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ P., D. (December 1983). "Q*Bert". Video Games (Volume 2, Number 3). Pumpkin Press: 65–66.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Richardson, Will (January 1984). "Get Hopping with Q*bert!". Electronic Games (Volume 2, Number 11). Reese Communications: 102.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Hacker, Randi (November 1983). "Q*Bert". Video Games. Fun & Games Publishing: 58.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (2008-03-17). "Top 10 Worst Atari 2600 Arcade Ports". IGN. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ Berman, Marc (December 1983). "Q*Bert". Video Games. Fun & Games Publishing: 62.

- ^ B., M. (April 1984). "Q*Bert". Video Games (Volume 2, Number 7). Pumpkin Press: 60.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Duberman, David (December 1983). "Product Reviews: Two from Parker Brothers". Antic. 2 (9): 124.

- ^ Leyenberger, Arthur (January 1984). "The 1983 Outpost: Atari Computer Game Awards". Creative Computing. 10 (1): 242–247.

- ^ "Vodafone calls Sony Pictures Mobile for new games and entertainment services". Vodafone. 2003-09-05. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Falcon, Robert (2006). "Q*Bert Mobile Review". Modojo. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ French, Michael (2006-02-12). "Q*Bert: An arcade classic hops to mobile". Pocket Gamer. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "Q*Bert". Airgamer. 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "An Introduction to Mobile Gaming". Gamespot. 2004-04-28. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Sinclair, Brendan (2007-02-16). "Q*Bert hops to PS3". Gamespot. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ a b Gerstmann, Jeff (2007-02-27). "Q*bert Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ Leadbetter, Richard (2007-04-14). "Q*Bert". Eurogamer.net. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Gutman, Dan (April 1984). "The Clones of Q*Bert". Computer Games (Volume 3, Number 1). Carnegie Publications: 48–51.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "The Thrill is Gone". PC Magazine. 3 (10). Ziff-Davis: 286. May 29, 1984.

- ^ Murphy, Brian J. (May 1984). "Cubit". InCider. Ziff-Davis: 127–128.

- ^ "Pogo". Crash (4). Newsfield: 84. May 1984.

- ^ "Spellbound". Crash (6). Newsfield: 51–52. July 1984.

- ^ "Hubert". Crash (10). Newsfield: 139. November 1984.

- ^ "Ruby-Spears Productions – About Us". Ruby-Spears Productions. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ a b Sharkey, Scott. "Top 5 Classic Videogame Cartoons". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ "Q*bert @ The Cartoon Scrapbook". Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (2012-11-03). "Wreck-It Ralph Cheat Code: Which Video Games Get Shout-Outs?". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Johnson, Phil; Lee, Jennifer, Wreck-It Ralph (screenplay) (PDF), Walt Disney Studios, retrieved 2014-07-11

- ^ "All of this to play Q-Bert?!". Ultima Adventures. 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ^ "Chick Cancer". Family Guy. Season 5. Episode 7. 2006-11-26. Fox Broadcasting Company.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "Anthology of Interest II". Futurama. Season 3. Episode 18. 2002-01-06. Fox Broadcasting Company.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Canning, Robert (2009-03-23). "The Simpsons: "In the Name of the Grandfather" Review". IGN. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ^ "In the Name of the Grandfather". The Simpsons. Season 20. Episode 14. 2009-03-22. Fox Broadcasting Company.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Stillman, Josh (2012-10-10). "'Robot Chicken' tackles 'Street Fighter'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "James Bond: Reply All/Randy Savage: 9th Grade Wrestler (2013): Connections". IMDb. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Imaginationland: Episode III (2007): Connections". IMDb. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Q*bert High Score Marathon Rankings". Twin Galaxies. Archived from the original on 2009-06-23. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ^ Epstein, Rick (2013-02-18). "Man claims world record by playing Q*bert for 84 hours in Hunterdon arcade". nj.com. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Morris, Chris (2013-02-19). "Man plays Q*bert for more than 80 hours, breaks 30-year-old record". Yahoo! Games. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008-03-11). "About Twin Galaxies". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ "Q*bert High Score Tournament Rankings". Twin Galaxies. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ^ "Q*bert Interview". Tomorrow's Heroes. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ a b Campbell, Stuart (January 2008). "A Whole Different Ball Game". Retro Gamer (45). Imagine Publishing: 49.

- ^ a b c "Q*bert's Qubes Videogame by Mylstar (1983)". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ a b c Ahl, David H. (April 1985). "1985 Winter Consumer Electronic Show". Creative Computing. 11 (4): 50.

- ^ a b "Q*bert's Qubes – Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Missing pipe in:|first=(help) - ^ Ahl, David H. (April 1985). "1985 Winter Consumer Electronics Show". Creative Computing. 11 (4). Ziff-Davis: 51.

- ^ "Q*bert's Qubes for Colecovision – Technical Information". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ "Q*bert's Qubes for Atari 2600 – Technical Information". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ^ "Q*Bert (Konami)". AM Life (in Japanese) (3). Kabushiki Kaisha Amusement: 10. March 1983.

- ^ "Qbert: De toutes les couleurs!". MSX News (in French) (5). Sandyx S.A.: 12. September/October 1987.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Q*Bert: The Arcade Hit Leaps to Your Game Boy". Game Informer (Spring 1992). Funco: 46–47. Spring 1992.

- ^ "Q*bert 3 for SNES". MobyGames. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Davis, Warren. "The Creation of Q*Bert". Coinop.org. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Weiss, Brett A. "Q*bert 3 – Overview". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ "IGN: Q*bert 3". IGN. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ a b Weiss, Brett A. "Q*bert – Review". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ a b Rice, Kevin (May 2001). "Q*bert Review". Next Generation Magazine. Imagine Media: 82.

- ^ "Q*Bert". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 2004-12-10. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "iTunes Preview: Q*Bert Deluxe". Apple. Archived from the original on 2010-03-11. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2010-03-01 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Q*bert 2005". Download.com powered by Cnet. CBS Interactive Inc. 2005-05-02. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ^ "Q*bert Rebooted brings the franchise back to Steam, mobile and tablets". Polygon. Vox Media. 2014-07-02. Retrieved 2014-07-03.

- 1982 video games

- Arcade games

- Atari 2600 games

- Atari 5200 games

- Atari 8-bit family games

- Cancelled ZX Spectrum games

- ColecoVision games

- Columbia TriStar

- Commodore 64 games

- Commodore VIC-20 games

- Dreamcast games

- Game Boy games

- Intellivision games

- IOS games

- Video games with isometric graphics

- Mobile games

- MSX games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Platform games

- PlayStation games

- PlayStation Network games

- Puzzle video games

- Sony mobile games

- Video games developed in the United States

- VAP (company) games

- Videopac games

- Gottlieb video games

- Ultra Games video games

- Video games inspired by M. C. Escher

- Media franchises