Hellingly Hospital Railway

The Hellingly Hospital Railway was a light railway owned and operated by East Sussex County Council, used to deliver coal and passengers to Hellingly Hospital, a psychiatric hospital near Hailsham, via a spur from the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway’s Cuckoo Line at Hellingly railway station.

The railway was constructed in 1899 and opened to passengers on 20 July 1903, following its electrification in 1902. After the railway grouping of 1923, passenger numbers declined so significantly that the hospital authorities no longer considered passenger usage of the line to be economical, and the service was withdrawn. The railway closed to freight in 1959, following the hospital's decision to convert its coal boilers to oil, which rendered the railway unnecessary.

The route took a mostly direct path from a junction immediately south of Hellingly Station to Hellingly Hospital, past sidings known as Farm Siding and Park House Siding respectively, used as stopping places to load and unload produce and supplies from outbuildings of the hospital. Much of the railway has since been converted to footpath, and many of the buildings formerly served by the line are now abandoned.

Construction and opening

In 1897, East Sussex County Council purchased 400 acres (160 ha) of land at Park Farm, about three miles (5 km) north of Hailsham, from the Earl of Chichester, to be the site of a new county lunatic asylum which would eventually become known as Hellingly Hospital.[1] Construction work on the hospital began in 1900, to the design of George Thomas Hine,[2] who had designed the nearby Haywards Heath Asylum.[3] Building materials were transported to the site by means of a 1+1⁄4 mile (2 km) standard gauge private siding, from the goods yard at Hellingly railway station on the Cuckoo Line. The connection was built by the asylum's construction firm, Joseph Howe & Company, and was authorised by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR) on the condition that East Sussex Council paid the estimated cost of £1,700.[4]

A small wooden platform was built at Hellingly railway station, opposite the main line platform. This had no connection to the station buildings and was used only for the transfer of passengers between mainline and hospital trains, and kept chained off when not in use.[5] Coal yards and sidings were also built at Hellingly station. The hospital opened to patients, and the railway to passengers, on 20 July 1903.[6]

Route

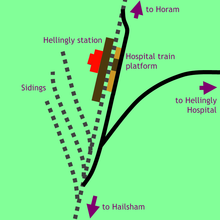

The railway left the Cuckoo Line at Hellingly Station. Although the railway joined the Cuckoo Line at both the northern and southern ends of the platform, virtually no through trains ever ran. Due to the arrangement of the lines at the junction between the Cuckoo Line and the Hospital Railway, passenger services to and from the hospital needed to reverse to the south of Hellingly station.[7]

After leaving the mainline, immediately south of Hellingly, the railway passed over two gated level crossings, at Park Road and New Road. A single siding on the west of the line beyond the crossings, known as Farm Siding, was used as a collection point for the farm's agricultural produce in the early years of the railway, but later fell out of use.[7] About halfway between Hellingly and the hospital the line entered the hospital grounds, passing to the west of Park House Siding, which served the hospital's Park House annexe.

As it approached the hospital, the line split; the southern fork led to a siding to the northwest of the hospital, while the other turned sharply east and south through almost 180° before splitting again. One fork ran into a large workshop and the other led to a short platform, which was initially used for passenger traffic. Following the suspension of passenger services it was converted into a coal dock.[8]

The line had no signals or automatic points to control the switching between lines at the railway's junctions with the main line and with the sidings. On the approach to a level crossing the driver's mate ran ahead with a red flag, to stop the traffic; he also manually operated the points.[9]

Motive power

Joseph Howe & Company used an 0-4-0 saddle tank locomotive to transport building materials during the hospital's construction. The locomotive was purchased new in 1900, and sold in 1903 following the completion of the hospital and electrification of the line.[10]

In 1902, the decision was taken to electrify the railway using power generated from the hospital's own power plant which was also connected to the National Grid. The line was electrified at 500V DC using a single overhead line.[7]

Engineers Robert W. Blackwell & Co provided a small 0-4-0 electric locomotive capable of pulling two loaded coal wagons. It is not known where the locomotive was manufactured, as the company has no record, but the design of the controls suggests that it may have been imported from Germany.[11] A small railcar with space for 12 passengers was also provided. The locomotive and the railcar were each fitted with a single trolley pole used to transfer electricity from the live overhead wire to the engine.[12] The passenger car was used for the duration of passenger services on the line, and the locomotive from the electrification of the line until its closure in 1959. At that time, it was the oldest operational electric locomotive in the British Isles.[7][13]

Operations

Following the railway grouping of 1923, the LBSCR became a part of the newly-formed Southern Railway and the agreements between the hospital (renamed the East Sussex Mental Hospital in 1919) and the LBSCR were updated. The wooden platform at Hellingly station was drastically shortened in 1922.[14] Because service levels depended on patient numbers and the hospital's coal and food requirements, the line never operated to a timetable.[7] By 1931, passenger numbers had fallen to such an extent that the hospital authorities no longer considered passenger usage of the line to be economical, and the passenger service was withdrawn. The passenger car was moved to the hospital grounds, fitted with an awning, and became the hospital's sports pavilion.[15] The wooden platform at Hellingly station was removed in 1932,[16] and the platform at the hospital end was converted into a coal bay.[8]

There were only two minor accidents throughout the existence of the line; a car which collided with the locomotive whilst driving through the hospital grounds, and a wagon whose brakes failed whilst stabled at Farm Siding, which rolled down the line to Hellingly station.[17]

On 22 November 1939, plans were put in place for the restoration of passenger services on the line, to allow ambulance trains to reach the hospital, and authorisation was given for their operation. However, the line was never used to transport patients, as although Park House was used as a hospital by the Canadian Army during the Second World War, patients were discharged by ambulance trains at Hellingly station and transferred to Park House by road.[14]

Closure

In the late 1950s, the hospital—under the control of the Hailsham Hospitals Management Committee since the 1948 establishment of the National Health Service—decided to convert the hospital's boilers from coal to oil. The railway was therefore no longer needed to transport coal; the last load was delivered on 10 March 1959, and the empty coal wagon returned to Hellingly on 25 March 1959.[18][19]

Under the terms of the agreement between the hospital authorities, the LBSCR, and its successors, the hospital authorities were obliged to keep the railway in good repair to allow its use by LBSCR/Southern/British Railways wagons. With a greatly reduced need for goods traffic to the hospital following the conversion of the boilers, it was decided that the railway was not worth the expense of continued maintenance and necessary upgrading, and the line was officially closed on 25 March 1959 following the departure of the last coal wagon.[19]

The line was used for irregular and occasional excursions by railway enthusiasts for a short period after its official closure, using the electric locomotive and a brake van borrowed from British Railways.[7] The exact date of the last running over the line is not recorded; the last recorded use of the line was an excursion organised by the Norbury Transport and Model Railway Club on 4 April 1959, but it is known that later excursions were run on the line before the track was lifted.[19] In the early 1960s a railway society in Yorkshire proposed to buy the track as a preserved railway. However, as the psychiatric hospital was still open the request was not considered practical,[19] and the track was lifted in the early 1960s. The fittings and locomotive were disposed of by H.Ripley and Sons of Hailsham.[7]

Present day

The Cuckoo Line closed shortly after the Hospital Railway. Hellingly station closed to passengers on 14 June 1965, and to goods traffic on 26 April 1968. The station building (complete with platform) is now a private residence, and the Cuckoo Line trackbed was converted to the Cuckoo Trail long-distance footpath in 1990.[20] Much of the route of the former Hospital Railway is also now a footpath.[21]

Traces of the railway can still be seen today, including a cast iron pole which held the overhead cable, the engine shed, and a short section of track.[22][23] Although Hellingly Hospital remains open, the services it offers are now reduced. The main building and Park House are both abandoned and derelict, but other parts of the complex continue to offer mental health services.[24] As of February 2007[update] it was planned to convert the entire hospital site into a housing complex consisting of 239 dwellings.[2][25]

References

Notes

- ^ Reflecting changing attitudes to, and terminology within, the field of psychiatric medicine, the hospital went through multiple renamings in its lifetime. Known as the County Lunatic Asylum prior to opening, it was opened in 1903 as the East Sussex County Asylum. On 28 June 1919 it was renamed the East Sussex Mental Hospital. Following the nationalisation of the health service in 1948, the formal name gradually declined in usage, and by the time of the closure of the main hospital building in 1990 it was always referred to as Hellingly Hospital. The name "Hellingly Hospital" was used informally (and in semi-official material such as staff publications) throughout the existence of the hospital, and the railway line was known as the "Hellingly Hospital Railway" from the outset.

- ^ a b "Former asylum to be converted to flats". The Argus. 7 February 2007. Retrieved on 20 June 2008.

- ^ Harding, p. 4

- ^ Elliott, p. 47

- ^ Mitchell & Smith, § 72

- ^ Harding, p. 6

- ^ a b c d e f g Stones, H.R. (December 1957). "The Hellingly Hospital Railway" (PDF). Railway Magazine. 103 (680): 869–872. Retrieved on 29 May 2008.

- ^ a b Harding, p. 16

- ^ Harding, p. 23

- ^ Harding, p. 5

- ^ Mitchell & Smith, § 74

- ^ Mitchell & Smith, § 73

- ^ Elliott, p. 53

- ^ a b Harding, p. 10

- ^ Harding, p. 21

- ^ Mitchell & Smith, § 76

- ^ Harding, p. 24

- ^ Harding, p. 11

- ^ a b c d Harding, p. 25

- ^ "The Cuckoo Trail" (PDF). East Sussex County Council. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Hellingly Walk" (PDF). East Sussex County Council. 2005. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Harding, p. 28

- ^ Catford, Nick (1995). "Disused Stations Site Record: Hellingly Hospital Railway". Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Wealden Local Plan: Hellingly Hospital" (PDF). Wealden District Council. December 1998. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Review Committee Minutes" (PDF). Wealden Council. 19 July 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

Bibliography

- Elliott, A.C. (1988). The Cuckoo Line. Didcot, Oxon: Wild Swan Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-906867-63-0.

- Harding, Peter A. (1989). The Hellingly Hospital Railway. Woking: Peter A. Harding. ISBN 0-950941-45-X.

- Mitchell, Vic (1986). Branch Lines to Tunbridge Wells from Oxted, Lewes and Polegate. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-32-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Model of the Hellingly Hospital Railway, built by Phil Parker

- Photographs of the remains of the Hellingly Hospital Railway

- Hellingly Hospital at County Asylums: gives a brief overview of the hospital's history and current status, as well as links to other sites relating to the hospital

- Hellingly Hospital today at Abandoned Britain