Le Puy Cathedral

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (September 2024) |

| Le Puy Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of the Annunciation of Our Lady, Le Puy | |

Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-l'Annonciation du Puy | |

| |

| |

| 45°2′44″N 3°53′5″E / 45.04556°N 3.88472°E | |

| Location | Le Puy-en-Velay, Auvergne |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral, Basilica |

| Dedication | Annunciation |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architectural type | Basilica |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 11th century |

| Completed | 13th century |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay |

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame |

| Designated | 1998 |

| Part of | Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France |

| Reference no. | 868 |

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame et ses dépendances |

| Type | classé |

| Designated | 1862 |

| Reference no. | PA00092743 |

Le Puy Cathedral (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-l'Annonciation du Puy) is a Catholic church located in Le Puy-en-Velay, in the French region of Auvergne. The cathedral is a national monument. It has been a centre of pilgrimage in its own right since before the time of Charlemagne, as well as being a stopover on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. Since 1998 it has been part of a multi-location UNESCO World Heritage Site along France's Santiago pilgrimage routes. It is the seat of the Bishop of Le Puy.

The cathedral forms the highest point of the city, rising from the foot of the Rocher Corneille. Constructed over centuries, it contains architecture of every period from the 5th century to the 15th, which gives it an individual appearance. The bulk of the construction, however, dates from the first half of the 12th century.

Black Madonna and pilgrimage

[edit]

A town called Anicium existed on the site since at least the 6th century. Fragments of Roman temple sculpture were reused in the walls of the cathedral, and Roman funeral monuments, and Paleochristian sculptures and other artifacts have been found nearby. These fragments mention the name of an early bishop, Scutaire, and date from late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. (They are now found in the Crozatier Museum in Le Puy).[1]

Documents from the period indicate that the early Christian church contained a celebrated image of the Virgin Mary and child, made of ebony. According to some sources, the statue was dressed in gowns made of gold and other precious fabrics. The cult of the so-called Black Madonna was found in many other French churches of the time and helped attract pilgrims. The original statue was destroyed in 1794 during the French Revolution, but many illustrations of it still exist. It was replaced in the 19th century by a new statue, now on the altar.[2]

Beginning in the 10th century Le Puy became a major stop on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. With the influx of pilgrims, the size of the cathedral chapter grew to forty priests, and the chapter constructed a "Hôtel-Dieu" or residence for impoverished pilgrims. A large number of chapels, convents, schools, and other religious institutions were founded around the cathedral as a consequence of the pilgrimage.[2]

The Carolingian and Romanesque cathedral

[edit]The new cathedral and its cloister were built close to the old church, at the highest point in the town, next to a massive rock butte, the Corneille. The cloister was built like a fortress, surrounded by a wall and fortified gates. It was governed exclusively by the clergy, and even contained its own prison, in a stone tower.[2] Excavations from 1992 to 1995 found vestiges of foundations of the earlier church, dating from the 9th century, These were reused in the 10th century for the construction of a larger church in the Carolingian style; it had a nave and collateral aisles, covering three traverses; a choir with two rectangular apse chapels attached to the lower side; and a flat apse on the west end.

Beginning in the mid-11th century, this church was enlarged further; the choir was preserved, but a large transept was added, with tribunes covering the apse chapels. The wider new nave had four traverses. The rounded barrel vaults of the nave were supported by cross-shaped pillars for the central nave and double columns and pilasters for the transept. The crossing of the transept was covered with a dome, over which was constructed an octagonal lantern tower.[3][2]

The new cathedral, with a cloister, was built against a steep hillside, and a new point of access from the town below was needed. A new porch was built on the west side just below the cathedral, with a stairway leading up to the nave. In the 12th century, this lower porch was enlarged with the construction of two new chapels, and the portal was given large doorways of cedar wood, and the monumental west front covering the porch was constructed with a decoration of multicoloured stone. From the porch at the bottom to the nave at the top. All of the structure was decorated with multicolour stone and fresco painting.[4]

The second part of the 12th century saw the partial reconstruction of the walls of the nave, and the reconstruction of the Chapel of Saint Martin on the west side, plus the addition of cupolas which replaced the old vaults of the nave. The pointed Gothic arch made its first appearance, and new porches were added to the angles of the transept and chevet.[5]

As the pilgrimage flourished, the complex of church buildings was expanded around the cloister on the north side of the cathedral. This included rich sculptural and polychrome decoration of the galleries and walls, and the construction of a grim square new tower, the Saint-Mayol tower, which served as a prison for the chapter. This tower, except for the lower two levels, was demolished in 1948.

On the west side of the complex was the Hotel-Dieu, the massive guest house for poor pilgrims, and the building of the Machicoulis (Named for its castle-like upper walls) which was a depot and kitchen for the chapter and the large Hotel-de-Dieu next to it, as well as a defensive structure if needed. Each of the five stories of the building had its own entrances. To the east of the cloister, and north of the transept of the cathedral, was the chapter house, the headquarters and residence hall for clergy, built in the last part of the 12th century. The oldest structure to the east is a Romanesque portal with sculpture on Rue Grasmement dating to the mid-12th century, which was formerly the entrance of the medieval hospital,[5]

After 1375, the west front had to be reinforced by a new buttress, and several of the vaults of the nave had to be rebuilt. In 1427, an earthquake caused serious damage to the structure, and in 1527, the vaults of the north transept had to be rebuilt. In 1516 lightning struck the bell tower, causing debris to fall onto the roof of the chapel of the Holy Crucifix below. Some modifications were made to the Romanesque features; larger windows were installed north transept, and in the adjoining parts of the nave. The whole complex suffered from a lack of maintenance; roofs leaked, damaging the masonry of the vaults below.[6]

17th–18th centuries

[edit]-

Procession marking the end of the plague (1630)

In the 17th century, the bishop Armand de Bethune undertook renovations and a program of decoration in the more classical French style, with clear glass windows bringing more light and lavishly decorated furniture, as well as a new organ, a new pulpit, and a new bishop's throne. He also constructed a monument to the King of Poland, John III Sobieski, a relative of the bishop who fought successfully against the Russians, the Swedes and the Turks.[6]

Between 1723 and 1727, the Grand Altar of the Virgin was put into place. It is covered with plaques of coloured marble and decorated with sculpture by the Italian sculptor Caffieri, and now features a recreation of the statue of the original Black Madonna, destroyed during the French Revolution.

At the end of the 18th century, the cathedral was in serious need of structural reinforcement and consolidation, as attested by the Director of Public Works of Languedoc province. However, Bishop Marie-Joseph de Galard chose instead to carry out a large-scale program of interior redecoration. He relocated the main stairway giving access to the building away from the nave to the cloister, where a new door was cut into the west wall. The medieval rood screen separating the choir and nave and surrounding choir screen were removed, and the interior was stripped of medieval decoration and redecorated with moulded plaster and false vaults, Some portions which were too difficult to remodel were simply abandoned; the north transept was closed and the south transept was turned into a dormitory.[7]

19th century

[edit]-

The cathedral in 1836, before restoration

-

Project for a new stained glass window (1848)

-

The church in 1888, after restoration

The French Revolution closed the cathedral and saw it deteriorate further. The new bishop, Louis Jacques Maurice de Bonald, did not take charge of the cathedral until 1823. A program of renovation finally began in 1844, under a new bishop, Pierre-Marie-Joseph Darcimoles, with the support of the Ministry of Cults of the French government. It was conducted by architect Aymond Gilbert Mallay, under the supervision of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Mallay proposed to demolish all of the recent reconstructions and to return the cathedral to its medieval appearance. He demolished the new bell tower that had been built over the transept and completely reconstructed the transept and its vaults. He rebuilt the transept higher, with new pillars, and covered the vaults of the nave with Neo-Romanesque cupolas, though these had not existed before. He restored the old apse and proposed that Neo-Romanesque murals should cover the interior of the transept. This last idea was vetoed by Prosper Mérimée, the head of the French government's program to restore medieval landmarks.[8]

Mallay modified the stairway to the nave on north side and built a new stairway on the south side. In 1846 he demolished the old west front and rebuilt it entirely, followed by the first two traverses of the nave. The cloister, next to the church was entirely redone between 1850 and 1852. Mallay retired in 1853, but his successors continued the project, demolishing the old chevet at the east end and replacing it with a new version that matched the transept and nave. They also demolished the Gothic sacristy, since it was not in harmony with Romanesque style. The last project was the bell tower, which was extensively modified and its upper three sections entirely rebuilt.[8]

20th century

[edit]In 1905 the church officially became the property of the French State, with exclusive use granted to the Catholic Church. In 1989, the French state began a new program to clean and embellish the building. The windows were cleaned to bring in more light; the old stairway, closed in the 18th century, was restored; the choir was given a new altar; the murals were cleaned and the organ was moved to a new tribune in the nave and restored in 1999. In 2004 and 2005 the west front and its murals were also cleaned and restored.[8]

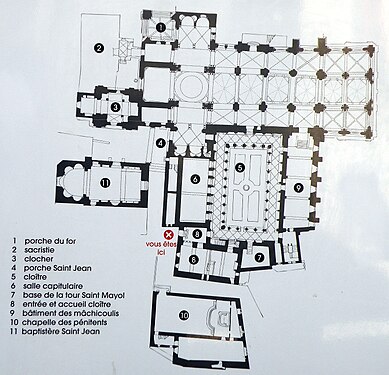

Plan

[edit]-

Plan of the cathedral

-

The cathedral and its cloister and buildings seen from above

The cathedral

[edit]West front

[edit]-

The approach to the west front

-

View to the west from inside central portal

The plan of the cathedral is largely determined by the steep slope upon which it is built. Before the end of the 19th century, access to the cathedral was by a steep narrow street lined with shops selling pilgrimage souvenirs, which led into a large space under the cathedral floor, and from which pilgrims mounted a separate stairway emerging near the altar. The current stairway was built at the end of the 19th century and goes directly up to the nave.

The facade, or west front of the cathedral is in the form of a large arch of triumph, with three portals and three levels. The portals are considerably lower than the floor of the nave. It is constructed of white sandstone and dark volcanic stone, Through it passes a stairway of sixty steps that comes up from outside the cathedral through the entrance arcades and climbs to the level of the nave.

On the lowest level, the three portals open to the space beneath the first bays of the nave. The level above has three windows that give light to the nave; at the top are three triangular frontons, or triangular gables. The window of the central fronton admits light to the nave, while the others have no glass and open onto the roof of the collateral aisles.

West porch

[edit]-

Decoration of the west porch

-

Sculpture of the tetramorph or bull, the symbol of Saint Luke, on a column in the west porch (13th c.)

-

Image of Saint Stephen, west porch

-

The cedar wood doors on the west front porch warn the impure not to enter

To reach the nave of the church a visitor must walk up sixty steps on a monumental stairway from the street to the west porch, and then another sixty steps to the nave. The porch or terrace of the cathedral was constructed in the 11th century on the site of the pre-Romanesque church. It was expanded in the mid-12th century when the church above was enlarged, and given massive pillars, columns and pilasters to form three traverses and three grand arcades.[9]

The west porch is like a church in itself beneath the cathedral, with some of the oldest and best-preserved original decoration. There are two chapels within the porch, dedicated to Saint Martin (south side) and Saint Luke (north). Their facades are from the original 11th-century church, before the construction of the two western traverses in the mid-12th century. The cedar doors, the carved and painted doors to the porch, were installed at the end of the 12th century. An inscription in Latin on the walls of the stairway warns in impure not to enter.[10]

The frescoes from the 11th and 12th centuries decorate the chapels, particularly on the walls of the central stairway, in a Byzantine art style and dating to around 1200. On the south wall is a Transfiguration scene depicting Christ with Moses and Elijah, and the apostles John, James, and Saint Peter at their feet. On the archway above them are frescoes of the dove of the Holy Spirit being presented by angels, and above that Saint Lawrence and Saint Stephen holding the palm fronds that identify martyrs.[9]

On the opposite wall of the stairway are frescoes from the same period depicting the Virgin Mary in majesty, on a seat representing wisdom, before a curtain held by angels and by the figures of the prophets Ezekiel and Jeremiah. She presents her child before her.[10]

In 2004, excavations of the porch uncovered additional 13th-century inscriptions and painted images of Saint Christopher, the patron saint of the pilgrims en route to Saint-Jacques do Campostelle. A stucco sculpture on another column depicts a tetramorph or image of a bull, the symbol of Saint Luke.

While most of the vaults in the porch are the rounded Romanesque barrel vaults and groin vaults, the porch has several vaults with more pointed arches, a feature of Gothic architecture, added in later reconstructions of the 14th and 18th century.[11]

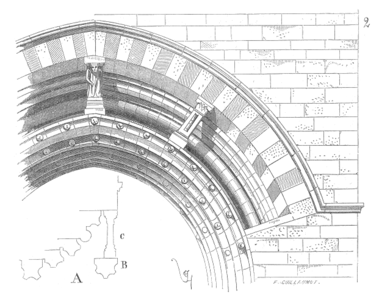

Porche du For or Papal Porch and the Porch Saint-John

[edit]-

Etresillon of the porch, by Viollet-le-Duc

-

The Porch du For

-

Column of the porch

-

Pillars of the Porche du For

-

Doors of Porch Saint-John, with vestiges of the Last Supper mosaics above them

While the traditional entrance to the church is through the west porch, the principal exit is through two portals on the northeast and southeast sides of the transept where it meets the chevet, at the east end. It is named for the Place du For, a square where the tribunal of the cathedral was located. This entrance was reserved for royal or papal pilgrims and was built largely of stones from the earlier Paleo-Christian cathedrals. On the lintel is an inscription SCUTARI PAPEVIVEDEO, probably for the Bishop Scutarius. On the inside of the portal is a reused Roman stone with an inscription honouring the Emperor Augustus and Adidon, probably the name of a local Roman deity. The other doorway, into the south arm of the transept, probably from the mid to late 12th century, and has very ornately carved capitals on the columns and the supports receiving the arches of the vaults depicting sirens and crowned heads. It also reemploys earlier stones; some have vestiges of geometric designs painted in the 11th century.[12]

The porch Saint John is on the north side of the cathedral, close to the baptistry, and covers over a section of street between the cathedral and the baptistry. It was reserved for the entry of kings, princes, the Dauphin of the Viennois region, and the governors of the provinces of the Languedoc region. One of the doorways is walled up; it formerly gave access to the north chapel in the chevet. The other doors, decorated with curling iron bars, open into the north transept. Above the doors there are the battered remains of a depiction of the Last Supper, with Christ in the centre. Christ also appears above, with angels on either side, with a backdrop of mosaics and small lobed circular openings.[13]

Nave

[edit]-

The nave facing east, toward the altar and choir, with pulpit on the left

-

The cupolas over the nave

-

The lantern tower over the transept

The nave is traditionally at the west end of the church, where the worshippers gather. separate from the choir at the east end, reserved for the clergy. At Le Puy the worshippers arrive at the nave by a stairway coming up from the west porch into the center of the church, at the fifth traverse, just west of the transept. The vessel of the nave has six traverses, each covered by a dome-like octagonal cupola supported by rounded arches upon massive trompes, or supporting pillars, at their angles. Alongside the central vessel there are two collateral aisles. Over the crossing of the nave and transept there is a lantern tower on top of the cupola.[14]

Choir, transept and chevet

[edit]-

The transept, lantern tower and cloister (1880s)

-

The choir and altar

-

The main altar

-

The new Black Madonna with a seasonal change of costume

-

History of Saint Andrew by Pierre Vaneau, gilded wood, (17th c.)

-

Gallo-Roman sculpture and inscriptions incorporated into the wall of the chevet

-

Romaneaque frescoes of women at the tomb of Christ, north transept

The choir, to the east of the nave, is the portion of the cathedral reserved for the clergy. The original choir was of modest size and had a relatively low ceiling. It was entirely rebuilt beginning in 1865 in a Neo-Romanesque style, with the height increased to twenty meters to match the nave, and given more abundant decoration, including of gilded palm leaves on the cornices, and marble and granite columns with gilded capitals. A large bay and window was opened to the east, and the choir was decorated with polychrome paintings in the vaults and pastels on the walls.

One remaining element of the 17th-century decoration is a carved and gilded panel of a scene from the life of Saint Andrew, by Pierre Vaneau, from the 17th century.[15]

Nearly all of the transept was torn down in 1844 and then rebuilt to its original proportions but with new decoration. The only surviving portion of the old transept is at the extreme north end, which retains some Romanesque frescoes.

The chevet, or east end of the cathedral, was entirely rebuilt beginning in 1865, along with the choir, to bring it to the same height as the nave, and with a large window. It was made in the Neo-Romanesque style, with colourful mosaics and arches around the new windows. The base of the chevet, near the well of cathedral, was decorated with sculptures and inscriptions from the early Romanesque cathedral.[15]

Organ

[edit]-

The cathedral organ

-

Detail of the organ case

The organ was installed in the nave in 1689. It has two faces and was made by Jean Eustache, with woodwork by Gabriel Alignon and sculpture by Francois Tireman and Pierre Vaneau. It was restored in 1827 and was classified as a historic monument in 1862.

Bell tower and Chapel of the Holy Saviour

[edit]-

Drawing of the bell tower by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1856)

-

The bell tower

-

Inside of the bell tower

-

Interior of the bell tower

-

Crypt of a bishop in the Chapel of the Holy Saviour

-

Tomb of a canon in the Chapel of the Holy Saviour

The bell tower is seven stories or fifty-six meters high and stands apart from the east end of the choir. Each of the square stories is slightly smaller than the one below. The lowest level of the tower dates to the first cathedral of the 11th century, and originally had large arcades open to the exterior, that were later filled with stone as the chapel rose higher.

The tower originally had a military as well as a religious function; the cathedral was required to have city watchmen stationed at the top of the tower, and the tower was crowned with a statue of a cock, a symbol of municipal authority Because of the military importance of the tower in surveilling the surrounding countryside for approaching enemies, the tower was spared destruction during the French Revolution.[16]

In the 12th century, the arches of the tower base were filled with stone, and it was expanded with the addition of a chapel, The Chapel of the Holy Saviour. The chapel is covered with a vault forming a quarter of a sphere and is used as a crypt for the sarcophagi of bishops and canons of the cathedral. These sarcophagi, set into niches in the walls, are covered with images of the persons and are surrounded by sculpted arches and decoration.

The levels of the tower are decorated by a series of bays and arches and have vivid sculptures of the period. In the 19th century, the top three levels of the tower were reconstructed, preserving their original form. Some of the original sculptures were replaced with copies and the originals put on display in the Crozatier Museum.[16]

In the 17th century, the tower housed twelve bells at the top. Today there are just four. The oldest and largest, with the deepest voice, is the bourdon, made in 1788 and named Marie-Joseph, the first name of Bishop de Galard, who commissioned it.[16]

The cloister

[edit]-

The cloister (12th century)

-

Capital of a column in the cloister

-

Capital of a column in the cloister (12th century)

-

Capital in the cloister

-

Capital in the cloister

-

Capital in cloister

-

Iron grill of the cloister

-

Polychrome painting on the column capitals

-

Gallery of the cloister

The four galleries of the multi-coloured cloister were constructed from the Carolingian period to the 12th century. It is connected to the remains of 13th century fortifications that separated the cathedral precincts from the rest of the city. Near the cathedral, the 11th-century baptistry of Saint John is built on Roman foundations.

The chapter buildings and the Chapel of the Dead

[edit]-

Crucifixion fresco, Chapel of the Dead

-

Detail of the Crucifixion fresco in the Chapel of the Dead (c. 1200)

-

Detail of Chapel of the Dead fresco

The buildings of the cathedral chapter, or members of the clergy, are placed to the east and west of the cloister. On the west side is the building of the Machicoulis, named for the battlements around the top of building, traditionally used to drop objects on attackers. In this case, the name is purely symbolic. The lower four levels were built in the 12th century, while the top level and battlements date to the early 13th century. It served as a meeting place, school, dining hall, library, treasury and chapel for the large number of clergy at the cathedral. In 1975, one space was designated the Chapel of relics, and dedicated to the display of the cathedral's collection of sacred relics. The former refectory, or dining hall, became a gallery for the display of the cathedral's collection of religious art. At one time a gallery at the top connected the terrace to the nearby tower of Saint Mayol.[17]

On the east side of the cloister is a large hall with a high arched ceiling, which opens onto the cloister. This was the chapter meeting hall and is called the Chapel of the Dead, for the funeral monuments of notable clerics around its walls. The south wall has a large mural, painted in about 1200, depicting the Crucifixion, with images of Saint Mary, Sant John, the sun, the moon, angels, and prophets. It was painted, according to an inscription in Latin on the wall, in "less than one hundred days." The style of the painting illustrates the evolution of painting from the Byzantine to the style of Gothic art.[18]

The baptistry (Church of Saint John)

[edit]-

The cathedral baptistery, or church of Saint-Jean, in the 19th century

The Church of Saint John is on the northeast side of the cathedral and is connected to it by the porch of Saint John. It served as baptistry of the parish until the French Revolution, It is at least as old as the cathedral itself, with portions, such as the apse, chevet, and parts of the walls on the north and south of the first traverse, which have been dated to between the 5th and 6th centuries by studies in 2004. Vestiges of the early baptismal font were also discovered. The church was heavily restored in the 19th century.[19]

The treasury – art and sculpture

[edit]-

The Holy Family, by Barthélemy d'Eyck (1450–1480)

-

Chest of reliquaries in the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament

-

Assumption of the Virgin sculpture, painted wood, by Pierre Vaneau (17th c.) on an arch over the nave

-

Sculpture of Saint James

Apart from the Romanesque frescos, the cathedral contains some notable works of painting and sculpture, largely from the 15th to 17th century. They are displayed in the Salles des États du Velay, in the sacristy of the cathedral. Works of art include "The Holy Family" by Barthélemy d'Eyck (1450–1480).

The cathedral also holds the Courgard-Fruman collection of more than three hundred liturgical vestments from different periods and countries, displaying their rich and varied embroidery. Seventy-six examples are on display in the Salle des États de Velay.

Another group of notable paintings are found in the Chapter Hall, on the walls of the library. They were commissioned by the head of the Chapter in 1501, with figures of women depicting the liberal arts; grammar, logic, rhetoric, and music, with and notable artists or scholars from each field.[19]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 19.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, pp. 57.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 29-30.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 64-65.

- ^ a b c Galland & de Framond 2005, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 64-658.

- ^ Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 65.

- ^ a b Galland & de Framond 2005, p. 69.

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Galland, Bernard; de Framond, Martin (2005). Ensemble cathédral Notre-Dame Le Puy-en-Velay (in French). Centre des monuments nationaux, Éditions du patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-7577-0370-0.

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Le Puy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Le Puy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.