Hyperoxaluria

| Hyperoxaluria | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bird's disease |

| |

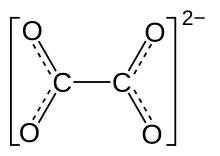

| Oxalate | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Hyperoxaluria is an excessive urinary excretion of oxalate. Individuals with hyperoxaluria often have calcium oxalate kidney stones. It is sometimes called Bird's disease, after Golding Bird, who first described the condition.

Presentation

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Causes

[edit]Hyperoxaluria can be primary (as a result of a genetic defect) or secondary to another disease process.[citation needed]

Type I primary hyperoxaluria (PH1) is associated mutations in the gene encoding AGXT, a key enzyme involved in oxalate metabolism. PH1 is an example of a protein mistargeting disease, wherein AGXT shows a trafficking defect. Instead of being trafficked to peroxisomes, it is targeted to mitochondria, where it is metabolically deficient despite being catalytically active. Type II is associated with GRHPR.[1]

Secondary hyperoxaluria can occur as a complication of jejunoileal bypass, or in a patient who has lost much of the ileum with an intact colon. In these cases, hyperoxaluria is caused by excessive gastrointestinal oxalate absorption.[2]

Excessive intake of oxalate-containing food, such as rhubarb, may also be a cause in rare cases.[3]

Diagnosis

[edit]Types

[edit]The types are the following:[citation needed]

- Primary hyperoxaluria

- Enteric hyperoxaluria

- Idiopathic hyperoxaluria

- Oxalate poisoning

Treatment

[edit]The main therapeutic approach to primary hyperoxaluria is still restricted to symptomatic treatment, i.e. kidney transplantation once the disease has already reached mature or terminal stages. However, through genomics and proteomics approaches, efforts are currently being made to elucidate the kinetics of AGXT folding which has a direct bearing on its targeting to appropriate subcellular localization. A child with primary hyperoxaluria was treated with a liver and kidney transplant.[4] A favorable outcome is more likely if a kidney transplant is complemented by a liver transplant, given the disease originates in the liver.[citation needed]

Secondary hyperoxaluria is much more common than primary hyperoxaluria, and should be treated by limiting dietary oxalate and providing calcium supplementation.[citation needed]

Controversy

[edit]Perhaps the key difficulty in understanding pathogenesis of primary hyperoxaluria, or more specifically, why AGXT ends up in mitochondria instead of peroxisomes, stems from AGXT's somewhat peculiar evolution. Namely, prior to its current peroxysomal 'destiny', AGXT indeed used to be bound to mitochondria. AGXT's peroxisomal targeting sequence is uniquely specific for mammalian species, suggesting the presence of additional peroxisomal targeting information elsewhere in the AGT molecule. As AGXT was redirected to peroxisomes over the course of evolution, it is plausible that its current aberrant localization to mitochondria owes to some hidden molecular signature in AGXT's spatial configuration unmasked by PH1 mutations affecting the AGXT gene.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Primary hyperoxaluria - Genetics Home Reference".

- ^ Surgery PreTest Self-Assessment and Review, Twelfth Edition

- ^ Marc Albersmeyer; Robert Hilge; Angelika Schröttle; Max Weiss; Thomas Sitter; Volker Vielhauer (30 October 2012). "Acute kidney injury after ingestion of rhubarb: secondary oxalate nephropathy in a patient with type 1 diabetes". BMC Nephrology. 13: 141. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-13-141. ISSN 1471-2369. PMC 3504561. PMID 23110375. Wikidata Q34461274.

- ^ "India News & Business - MSN India: News, Business, Finance, Sports, Politics & more. - News". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-05-09.