Evdokia Reshetnik

Evdokia Reshetnik | |

|---|---|

Євдокія Григорівна Решетник | |

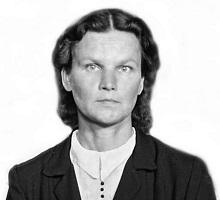

Reshetnik circa 1945 | |

| Born | Evdokia Grigoryevna Reshetnik 14 March 1903 Koshmanovka, Poltava Oblast, Russian Empire |

| Died | 22 October 1996 (aged 93) Kyiv, Ukraine |

| Other names | Evdokia Reshetnyk, Yevdokia Hryhorivna Reshetnyk |

| Occupation(s) | Zoologist, ecologist |

| Years active | 1924–1986 |

Evdokia Reshetnik (Ukrainian: Євдокія Решетник; 1 March 1903 O.S./14 March 1903 (N. S.) – 22 October 1996) was a Ukrainian zoologist and ecologist. She was a specialist in the mole-rats and ground squirrels of Ukraine, and was the first scientist to describe the sandy blind mole-rat of southern Ukraine in 1939. She played a key role in keeping the National Museum of Natural History at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine operable in the inter-war and immediate post-war periods, in spite of arrests by both the Gestapo and Soviet authorities. She was one of the people involved in hiding specimens of the museum to prevent them being taken by the Germans. She is known for arguing that ecology, species distribution, populations, utility, and variability, should be weighed before making determinations that labeled certain animals as pests and harmful to the environment. Though she was responsible for maintaining the historiography of scientific development in Ukraine, her own legacy was lost until the twenty-first century.

Early life and education

[edit]Evdokia Grigoryevna Reshetnik was born on 14 March 1903 (N. S.) in the village of Koshmanovka in the Poltava Oblast of the Russian Empire, in what is now Ukraine. Her father, Grigory Yefimovich Reshetnik, was a prosperous peasant who died before being de-Kulaked. He owned a sizeable acreage on which he raised cattle.[1] Probably because of her father's early death, Reshetnik was raised from childhood by her older sister and brother-in-law in Poltava. There she attended both primary school and seven years in gymnasium. In 1918, she began a three-year program in pedagogy, completed her practical work teaching at the local orphanage, and earned her teaching credentials from the Poltava Pedagogical University, under the rules of the Russian Institute of Public Education, in 1920.[2]

Continuing as a student there, Reshetnik studied biology until 1924, with classmates Oksana Ivanenko, Pavlo Tychyna, and her future husband, Yakov Khomenko. While she was studying, she simultaneously continued to teach at the orphanage. She graduated with a specialty in biology in 1924, and was hired to work at the Osnovianskyi District worker's school on the outskirts of Kharkiv as a zoology instructor.[2] Khomenko worked as a philologist and translator at the Institute of Linguistics and Literature.[3] Reshetnik and Khomenko married in 1926 and had a son, Emil, two years later. After passing her examinations in 1931, Reshetnik began graduate studies at Kharkiv State University in the Zoology Research Institute.[2] From 1933, she also worked as a researcher at the Kharkiv Scientific Research Station. She graduated in 1934, after a successful defense of her work, which focused on the study of larks.[4][Notes 1]

Career

[edit]Pre-war and war years (1935–1946)

[edit]In 1935, when the capital of Ukraine was transferred from Kharkiv to Kyiv, Reshetnik's husband was transferred with his employer and she followed him.[5] She found employment as a researcher at the Kyiv Zoo. In 1936, she was designated as a senior researcher at the I. I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, for which she served as secretary. In 1939, she published her paper describing Spalacidae (mole-rats) in Ukraine and the following year earned a Candidate degree in 1940,[6] although her diploma would not be awarded until 1946.[7] While on a research trip the following year in Chișinău, Bessarabia, the war caused Reshetnik to return to Kyiv. Boarding the academic evacuation train for Ufa, she disembarked at Poltava, where her son was staying with her sister.[6][8] She was also reunited with her husband at the train station.[8] The curfew made it impossible for her to pick up her son and continue on the evacuation train, so they remained in Poltava until October 1941, when the Germans invaded the city.[6] They then went back to Kyiv on horseback, a difficult and lengthy journey.[6][9]

After arriving in Kyiv, Reshetnik discovered her home had been ransacked and looted, so she and her son stayed with friends. Without work, she volunteered with the Red Cross, distributing clothes and food to captured Red Army prisoners, held at the Darnytsky concentration camp. The prisoners were fed peas, which were shared with Reshetnik who was able to take them home and feed her family. On 10 February 1942, Red Cross workers, including Reshetnik, were arrested by the Gestapo. She was also charged with collaborating with the newspaper Ukrainian Word, although she had no affiliation with the publication. After eighteen days of imprisonment, her bail was paid by colleagues, Mykola Charlemagne and Sergey Paramonov and Reshetnik was released.[10]

In May 1942, the Institute of Plant Protection and Pest Control was established by the Reich Commissariat of Ukraine in the National Academy of Sciences.[10][11] Reshetnik was hired to work under the direction of Charlemagne and she secured a position there for her son as a bookbinding student to prevent him being removed to Germany.[10] She conducted work on ground squirrels, gophers, and groundhogs at this institute until September 1943.[10][12] Of particular interest to the Germans was research into drugs and other means of eliminating pests, particularly rodents, which might endanger agricultural plants.[13] Near the end of the war, the Germans began moving the Zoological museum collections to Poznań, and other locations in Germany and Poland.[14] Reshetnik was actively involved in successfully hiding some of the specimens to prevent their removal.[15]

Post-war (1946–1986)

[edit]At the end of the war, Reshetnik was awarded a research specialist designation in zoology in 1946 and was hired to work at the Institute of Zoology of the Academy of Sciences, where she remained until 1950. During this time, she published two papers on her earlier study of ground squirrels. One of them, which was published in 1946, identified new subspecies of the speckled ground squirrel (Citellus suslica ognevi and Citellus suslica volhynensis).[7][16] In her works, Reshetnik pointed out that rodents could be valuable for their skins as well as their fat, which was widely used during the war as a food source.[17] She published extensive analyses about the ecology, species distribution, populations, and variability of the types of rodents throughout Ukraine.[18] In these works, she argued that the economic or usefulness of rodents should be weighed against the potential damage they might do.[19][20]

When the Soviets were restored to power, a period of repression began in Ukraine.[21] In 1948, Reshetnik's son was arrested for membership in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and deported to Mordovia. Soon after, her husband was also arrested and imprisoned. Both of them were required to serve eight-year sentences.[7][9] She faced several fabricated charges — that she was to have been shot by the Gestapo and since she was not must have been a collaborator; that she had friendships with questionable people, such as Charlemagne and Paramonov; and that she had plagiarized other people's work — among other accusations and denunciations from colleagues.[9][21] In 1951, Reshetnik was remanded to the Chernihiv Penal Colony, where she remained until 1955. Upon her release, Reshetnik began working as a district entomologist for the Kyiv-Sviatoshyn District Sanitary and Epidemiology Station. Between 1956 and 1957, she was rehabilitated by the authorities, and in 1961 allowed to return to the Institute of Zoology, where she remained until her retirement in 1986.[21]

Much of her work at the Institute of Zoology was spent curating the museum's collections. As a skilled authority and taxidermist, she expanded the zoological specimens with hundreds of samples of species. As an archivist, and one with intimate knowledge of how history treats scientists, she was a meticulous record keeper and made sure that the personnel files of her colleagues retained their most important works, even if they had been repressed by the government.[19] Among the biographies of Ukrainian scientists Reshetnik preserved were Charlemagne, Ivan Demyanovich Ivanenko (Ukrainian: Іван Дем’янович Іваненко), Sergey Medvedev, and Paramonov, among others.[22] In 1993, she dictated her memories of Olena Teliha to her son, because her eyesight was failing. The remembrance was published in the newspaper Ukrainian Word under the title "Моя Оленіана" ("My Oleniana") and told of their relationship when they were held by the Gestapo.[23]

Death and legacy

[edit]Reshetnik died on 22 October 1996, in Kyiv and was buried Sovsky Cemetery.[21] Despite her name being remembered in Ukraine because of the papers she had published, Reshetnik's biography was not retold until the twenty-first century.[1]

Selected works

[edit]

Reshetnik is primarily known for her research on rodents, particularly mole-rats and ground squirrels.[19] She published over twenty papers between 1939 and 1965 detailing new species and subspecies, including a unique blind mole-rat, Spalax arenarius, which she first identified in 1939 and is endemic to Ukraine.[19][24] Her work evaluated the ecology, varying shapes, and distribution of their populations.[19]

- Решетник, Є. Г. (1937). "До екології жайворонків в умовах району Асканія-Нова" [The Ecology of Larks in the Conditions of the Askania-Nova Region]. Збірник праць зоологічного музею (in Ukrainian) (20). Kharkiv, Ukrainian SSR: National Zoological Museum: 3–40.[5]

- Решетник, Є. Г. (1939). "До систематики i географічного поширення сліпаків (Spalacidae) в УРСР" [The Systematic and Geographical Distribution of Spalacids (Spalacidae) in the Ukrainian SSR]. Збірник праць зоологічного музею АН УРСР (in Ukrainian) (23). Kyiv, Ukrainian SSR: Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences: 3–21.[25]

- Решетник, Є. Г. (1946). "О новых подвидах крапчатого суслика Citellus suslica volhynensis subsp. nov. и Citellus suslica ognevi subsp. nov" [On a New Subspecies of the Speckled Ground Squirrel Citellus suslica volhynensis subsp. nov. and Citellus suslica ognevi subsp. nov.]. Бюллетень МОИП (in Ukrainian). 51 (6). Moscow, USSR: Moscow Society of Naturalists: 25–27.[25]

- Решетник, Є. Г. (10 March 1994). Хоменка, Еміля (ed.). "Моя Оленіана" [My Oleniana]. Українське слово (in Ukrainian). No. 10. Kyiv, Ukraine. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Reshetnik's biographer, Marina Korobchenko, believes that Reshetnik studied under Volodymyr Stanchinsky (Ukrainian: Володимир Станчинський), who headed the ecology department at the Zoology Research Institute between March 1931 and December 1933. He and fifteen of his assistants and students were arrested in 1933 on politically motivated charges. When Reshetnik graduated in 1934, her records showed she "defended her academic work" (Ukrainian: «захистила наукову роботу»), rather than identifying an academic field, a supervisor, or naming her dissertation, which Korobchenko notes was probably because it had been performed under Stanchinsky's guidance.[5]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Korobchenko 2016, p. 137.

- ^ a b c Korobchenko 2016, p. 138.

- ^ Opanasenko 2018, p. 100.

- ^ Korobchenko 2016, pp. 137, 139.

- ^ a b c Korobchenko 2016, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d Korobchenko 2016, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Korobchenko 2016, p. 142.

- ^ a b Zagorodnyuk 2021, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Opanasenko 2018, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d Korobchenko 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, pp. 17, 22.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, p. 35.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, p. 28.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Korobchenko 2016, p. 144.

- ^ Zagorodnyuk 2021, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b c d Korobchenko 2016, p. 143.

- ^ Korobchenko 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Korobchenko 2016, pp. 142, 144.

- ^ Rushin, Çetintaş & Yanchukov 2018, p. 21.

- ^ a b National Academy of Sciences 2002.

Bibliography

[edit]- Korobchenko, Marina (December 2016). "Євдокія Решетник (1903–1996) — видатна постать в історії академічної зоології та екології в Україні" [Evdokia Reshetnyk (1903–1996) — An Outstanding Figure in the History of Academic Zoology and Ecology in Ukraine] (PDF). Proceedings of the National Museum of Natural History (in Ukrainian). 2016 (14). Kyiv, Ukraine: National Museum of Natural History at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: 136–146. doi:10.15407/vnm.2016.14.136. ISSN 2219-7516. OCLC 8173121205. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- Opanasenko, Julia V. (2018). "Забуті сторінки українського художнього перекладу (про маловідомих перекладачів детективної прози А. К. Дойла) [Forgotten Pages of Ukrainian Artistic Translation (About Little-Known Translators of A. K. Doyle's Detective Prose)" [Current Problems of Modern Translation Studies] (PDF). In Selivanova, O. O. (ed.). Актуальні проблеми сучасного перекладознавства. All-Ukrainian Scientific and Practical Conference — 30 May 2018, Bohdan Khmelnytsky National University of Cherkasy (in Ukrainian). Kyiv, Ukraine: Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. pp. 98–102. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Rushin, Mikhail; Çetintaş, Ortaç; Yanchukov, Alexey (October 2018). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Large-Bodied Blind Mole Rats in Ukraine Confirms the Position of Spalax arenariu" (PDF). In Váczi, Oliver; Németh, Attila (eds.). Book of Abstracts. VII. European Ground Squirrel Meeting & Subterranean Rodents Workshop at Budapest, Hungary 1-5 October 2018. Budapest, Hungary: Organizing Committee. p. 21. ISBN 978-963-89119-3-3.

- Zagorodnyuk, I.V. (2021). "Ховрахи війни: історія зоологічних досліджень та колекцій spermophilus в умовах райхскомісаріату україна" [Grocers of War: A History of Zoological Research and Spermophilus Collections under the Conditions of the Reich Commissariat of Ukraine] (PDF). Proceedings of the State Natural History Museum (in Ukrainian) (37). Lviv, Ukraine: National Academy of Ukraine: 17–38. doi:10.36885/nzdpm.2021.37.17-38. ISSN 2224-025X. S2CID 246645450. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Литература: (оригинальные описания таксонов, типовые экземпляры которых хранятся в зоологическом музее)" [Literature: (Original Descriptions of Taxa, Type Specimens of which Are Kept in the Zoological Museum)]. museumkiev.org (in Ukrainian). Kyiv, Ukraine: National Museum of Natural History at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.