Daur people

| Daur Woman from Inner Mongolia Daur Woman from Inner Mongolia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 131,992 (2010 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| People's Republic of China, in Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang and Xinjiang | |

| Languages | |

| Chinese, Daur | |

| Religion | |

| Tibetan Buddhism, Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongolic peoples, Khitan |

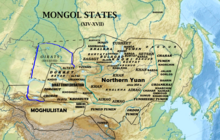

The Daur people (Khalkha Mongolian: Дагуур, Daguur; simplified Chinese: 达斡尔族; traditional Chinese: 達斡爾族; pinyin: Dáwò'ěr zú) are a Mongolic people in Northeast China. The Daur form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognised in the People's Republic of China. They numbered 131,992 according to the latest census (2010) and most of them live in Morin Dawa Daur Autonomous Banner in Hulun Buir, Inner Mongolia and Meilisi Daur District in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang of China. There are also some near Tacheng in Xinjiang, where their ancestors were moved during the Qing dynasty.

Language

The Dagur language is a Mongolic language. There is a Latin-based orthography which has been devised by a native Daur scholar. The Dagur language retains some Khitan substratal features, including a number of lexemes not found in other Mongolic languages. It is made up of three dialects: Batgan, Hailar, Qiqihar.

During Qing rule, some Daur spoke and wrote Manchu as a second language.[2]

History

Genetically, the Daurs are descendants of the Khitan, as recent DNA analyses have proven.[3] In the Qianlong Emperor's "钦定《辽金元三史语解》" (Imperially commissioned Translations of the History of Liao, History of Jin and History of Yuan) he retranslates "大贺", a Khitan clan described in the History of Liao, as "达呼尔". That is the earliest theory that claims Daurs are descendants of Khitans.

In the 17th century, some or all of the Daurs lived along the Shilka, upper Amur, on the Zeya and Bureya River. They thus gave their name to the region of Dauria, also called Transbaikal, now the area of Russia east of Lake Baikal.

By the mid-17th century, the Amur Daurs fell under the influence of the Manchus of the Qing dynasty which crushed the resistance of Bombogor, leader of the Evenk-Daur Federation in 1640. When the Russian explorers and raiders arrived to the region in the early 1650 (notably, during Yerofei Khabarov's 1651 raid), they would often see the Daur farmers burn their smaller villages and taking refuge in larger towns. When told by the Russians to submit to the rule of the Tsar and to pay yasak (tribute), the Daurs would often refuse, saying that they already paid tribute to the Shunzhi Emperor (whose name the Russians recorded from the Daurs as Shamshakan).[4] The Cossacks would then attack, usually being able to take Daur towns with only small losses. For example, Khabarov reported that in 1651 he had only 4 of his Cossacks killed while storming the town of the Daur prince Guigudar (Гуйгударов городок) (another 45 Cossacks were wounded, but all were able to recover). Meanwhile, the Cossacks reported killing 661 "Daurs big and small" at that town (of which, 427 during the storm itself), and taking 243 women and 118 children prisoners, as well as capturing 237 horse and 113 cattle.[4] The captured Daur town of Yaxa became the Russian town Albazin, which was not recaptured by the Qing until the 1680s.

Cattle and horses in the hundreds were looted and 243 ethnic Daur girls and women were raped by Russian Cossacks under Yerofey Khabarov when he invaded the Amur river basin in the 1650s.[5]

Facing the Russian expansion in the Amur region, between 1654 and 1656, during the reign of Shunzhi Emperor, the Daurs were forced to move southward and settle on the banks of the Nen River, from where they were constantly conscripted to serve in the banner system of the Qing emperors.

Russian Cossack soldiers slaughtered 1,266 households, 900 Daurs during the Blagoveshchensk massacre and Sixty-Four Villages East of the River massacre.[6]

When the Japanese invaded the area of present-day Morin Dawa in Inner Mongolia in 1931, the Daurs carried out an intense resistance against them.[7]

Konan Naito pointed out that Takri Kingdom where King Dongmyeong, a founder of Buyeo was born, as a country of Daur people who lived by Songhua River.[8]

Culture

There is a very noticeable hierarchic structure. People sharing the same surname are in groups called hala, they live together with the same group, formed by two or three towns. Each hala is divided in diverse clans (mokon) that live in the same town. If a marriage between different clans is made, the husband continues to live with the clan of his wife without holding property rights.

During the winter, the Daur women wear long dresses, generally blue in color and boots of skin which they change for long trousers in summer. The men dress in orejeros caps in fox or red deer skin made for winter. In the summer, they cover the animal's head with white colored fabrics or straw hats.

A customary sport of the Daur is Beikou, a game similar to field hockey or street hockey, which has been played by the Daur for about 1,000 years.[9]

Religion

Many Daurs practice shamanism. Each clan has its own shaman in charge of all the important ceremonies in the lives of the Daur.[10] However, there are a significant number of Daurs who have taken up Tibetan Buddhism.

During the Qing, the Daur knew a version of the Tale of the Nisan Shaman, in which the female shaman Ny Dan competed against her rivals at the Qing court, the Tibetan monks who managed to convince the Qing emperor to execute her. The Qing emperor is shown as a fool who is tricked by the lamas.[11]

Genetics

Genetic testing also showed that the C3b1a3a2-F8951 of the Aisin Gioro family came to southeastern Manchuria after migrating from their place of origin in the Amur river's middle reaches, originating from ancestors related to Daurs in the Transbaikal area. The Tungusic speaking peoples mostly have C3c-M48 as their subclade of C3 which drastically differs from the C3b1a3a2-F8951 haplogroup of the Aisin Gioro which originates from Mongolic speaking populations like the Daur. Jurchen (Manchus) are a Tungusic people. The Mongol Genghis Khan's haplogroup C3b1a3a1-F3796 (C3*-Star Cluster) is a fraternal "brother" branch of C3b1a3a2-F8951 haplogroup of the Aisin Gioro.[12] Haplogroup C3b2b1*-M401(xF5483)[13][14][15] has been identified as a possible marker of the Aisin Gioro and is found in ten different ethnic minorities in northern China, but completely absent from Han Chinese.[16][17][15]

The Daur Ao clan carries the unique haplogroup subclade C2b1a3a2-F8951, the same haplogroup as Aisin Gioro and both Ao and Aisin Gioro only diverged merely a couple of centuries ago from a shared common ancestor. Other members of the Ao clan carry haplogroups like N1c-M178, C2a1b-F845, C2b1a3a1-F3796 and C2b1a2-M48. People from northeast China, the Daur Ao clan and Aisin Gioro clan are the main carriers of haplogroup C2b1a3a2-F8951. The Mongolic C2*-Star Cluster (C2b1a3a1-F3796) haplogroup is a fraternal branch to Aisin Gioro's C2b1a3a2-F8951 haplogroup.[18] A genetic test was conducted on seven men who claimed Aisin Gioro descent with three of them showing documented genealogical information of all their ancestors up to Nurhaci. Three of them turned out to share the C3b2b1*-M401(xF5483) haplogroup, out of them, two of them were the ones who provided their documented family trees. The other four tested were unrelated.[19] The Daur families áolāshì 敖拉氏, áolēiduō'ěr 敖勒多尔氏, āěrdān 阿尔丹氏, énuò 额诺氏, áolātuōxīn 敖拉托欣氏 and the Manchu families áojiā (敖佳氏), Èjì (鄂济氏), guāěrjiā (瓜尔佳氏), wūxīlēi (乌西勒氏) were the ones that adopted the Chinese surname Ao.

Notes

- ^ Multicultural China: A Statistical Yearbook (2014), p349

- ^ Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- ^ Li Jinhui (2 August 2001). "DNA Match Solves Ancient Mystery". china.org.cn.

- ^ a b Вадим Тураев (Vadim Turayev), О ХАРАКТЕРЕ КУПЮР В ПУБЛИКАЦИЯХ ДОКУМЕНТОВ РУССКИХ ЗЕМЛЕПРОХОДЦЕВ XVII Archived 2004-12-30 at archive.today ("Regarding the omissions in published documents of Russian 17th-century explorers") (in Russian)

- ^ Ziegler, Dominic (2016). Black Dragon River: A Journey Down the Amur River Between Russia and China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Penguin. p. 187. ISBN 978-0143109891.

- ^ 俄罗斯帝国总参谋部. 《亚洲地理、地形和统计材料汇编》. 俄罗斯帝国: 圣彼得堡. 1886年: 第三十一卷·第185页 (俄语).

- ^ Bulag, Uradyn E. The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002. p.158

- ^ 李成市 (1998-03-25). 古代東アジアの民族と国家. Iwanami Shoten. p. 76. ISBN 978-4000029032.

- ^ McGrath, Charles (August 22, 2008). "A Chinese Hinterland, Fertile With Field Hockey". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ^ Humphrey, Caroline; Onon, Urgunge (1996). Shamans and Elders: Experience, Knowledge, and Power among the Daur Mongols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Rawski, Evelyn (2001). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-22837-5.

- ^ Wei, Ryan Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Yu, Ge; Huang, Yun-Zhi (November 2016). "Genetic trail for the early migrations of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (3). The Japan Society of Human Genetics: 407–411. doi:10.1038/jhg.2016.142. ISSN 1434-5161. PMID 27853133. S2CID 7685248.

- ^ Wei, Ryan Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Yu, Ge; Huang, Yun-Zhi (November 2016). "Genetic trail for the early migrations of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (3): 407–411. doi:10.1038/jhg.2016.142. PMID 27853133. S2CID 7685248.

- ^ Yan, Shi; Tachibana, Harumasa; Wei, Lan-Hai; Yu, Ge; Wen, Shao-Qing; Wang, Chuan-Chao (June 2015). "Y chromosome of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (6): 295–8. arXiv:1412.6274. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.28. PMID 25833470. S2CID 7505563.

- ^ a b "Did you know DNA was used to uncover the origin of the House of Aisin Gioro?". Did You Know DNA... 14 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Xue, Yali; Zerjal, Tatiana; Bao, Weidong; Zhu, Suling; Lim, Si-Keun; Shu, Qunfang; Xu, Jiujin; Du, Ruofu; Fu, Songbin; Li, Pu; Yang, Huanming; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2005). "Recent Spread of a Y-Chromosomal Lineage in Northern China and Mongolia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (6): 1112–1116. doi:10.1086/498583. PMC 1285168. PMID 16380921.

- ^ "Asian Ancestry based on Studies of Y-DNA Variation: Part 3. Recent demographics and ancestry of the male East Asians – Empires and Dynasties". Genebase Tutorials. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013.

- ^ Wang, Chi-Zao; Wei, Lan-Hai; Wang, Ling-Xiang; Wen, Shao-Qing; Yu, Xue-Er; Shi, Mei-Sen; Li, Hui (August 2019). "Relating Clans Ao and Aisin Gioro from northeast China by whole Y-chromosome sequencing". Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (8). Japan Society of Human Genetics: 775–780. doi:10.1038/s10038-019-0622-4. PMID 31148597. S2CID 171094135.

- ^ Yan, Shi; Tachibana, Harumasa; Wei, Lan-Hai; Yu, Ge; Wen, Shao-Qing; Wang, Chuan-Chao (June 2015). "Y chromosome of Aisin Gioro, the imperial house of the Qing dynasty". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (6). Nature Publishing Group on behalf of the Japan Society of Human Genetics (Japan): 295–8. arXiv:1412.6274. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.28. PMID 25833470. S2CID 7505563.

External links

- Unicode Manchu/Sibe/Daur Fonts and Keyboards

- The Daur ethnic minority (Chinese government site, in English)