Medieval Jerusalem: Difference between revisions

m spelling |

Copyediting/condensing, merging duplicated sections |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

==Mamluk control and Mongol raids== |

==Mamluk control and Mongol raids== |

||

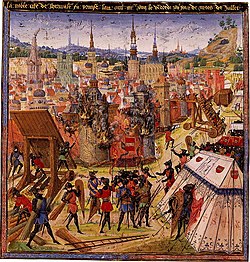

| ⚫ | [[Image:JacquesMolayPrendJerusalem1299VersaillesMuseeNationalChateauEtTrianons.jpg|thumb|"[[Jacques de Molay|Jacques Molay]] takes Jerusalem, 1299", a fanciful painting created in the 1800s by Claude Jacquand, and hanging in the "Hall of Crusades" in Versailles. In reality, though the Mongols may have been technically in control of the city for a few months in early 1300 (since the Mamluks had temporarily retreated to Cairo and no other troops were in the area), De Molay was almost certainly on the island of [[Cyprus]] at that time, nowhere near the landlocked city of Jerusalem.]] |

||

{{main|Mongol raids into Palestine}} |

|||

When al-Salih died, his widow, the slave [[Shajar al-Durr]], took power as Sultana, which power she then transferred to the Mamluk leader [[Aybeg]], who became Sultan in 1250.<ref>''Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages, 1250-1520'', p. 264</ref> Meanwhile, the Christian rulers of [[Antioch]] and [[Cilician Armenia]] subjected their territories to Mongol authority, and fought alongside the Mongols during the Empire's expansion into Iraq and Syria. In 1260, a portion of the Mongol army advanced toward Egypt, and was engaged by the Mamluks in [[Galilee]], at the pivotal [[Battle of Ain Jalut]]. The Mamluks were victorious, and the Mongols left the area. In early 1300, there were again some Mongol raids into Palestine, shortly after the Mongols had been successful in capturing cities in northern Syria; however, the Mongols occupied the area for only a few weeks, and then retreated again to Iran. The Mamluks regrouped and re-asserted control over Palestine a few months later, with little resistance. |

When al-Salih died, his widow, the slave [[Shajar al-Durr]], took power as Sultana, which power she then transferred to the Mamluk leader [[Aybeg]], who became Sultan in 1250.<ref>''Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages, 1250-1520'', p. 264</ref> Meanwhile, the Christian rulers of [[Antioch]] and [[Cilician Armenia]] subjected their territories to Mongol authority, and fought alongside the Mongols during the Empire's expansion into Iraq and Syria. In 1260, a portion of the Mongol army advanced toward Egypt, and was engaged by the Mamluks in [[Galilee]], at the pivotal [[Battle of Ain Jalut]]. The Mamluks were victorious, and the Mongols left the area. In early 1300, there were again some Mongol raids into Palestine, shortly after the Mongols had been successful in capturing cities in northern Syria; however, the Mongols occupied the area for only a few weeks, and then retreated again to Iran. The Mamluks regrouped and re-asserted control over Palestine a few months later, with little resistance. |

||

There is little evidence to indicate whether or not the Mongol raids penetrated Jerusalem in either 1260 or 1300. Historical reports from the time period tend to conflict, depending on which nationality of historian was writing the report. There were also a large number of rumors and urban legends in Europe, that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and were going to return it to the Crusaders. However, these rumors turned out to be false.<ref>Sylvia Schein, "Gesta Dei per Mongolos"</ref> The general consensus of modern historians is that though Jerusalem may or may not have been subject to raids, that there was never any attempt by the Mongols to incorporate Jerusalem into their administrative system, which is what would be necessary to deem a territory "conquered" as opposed to "raided."<ref>Reuven Amitai, "Mongol raids into Palestine (1260 and 1300)</ref> |

There is little evidence to indicate whether or not the Mongol raids penetrated Jerusalem in either 1260 or 1300. Historical reports from the time period tend to conflict, depending on which nationality of historian was writing the report. There were also a large number of rumors and urban legends in Europe, that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and were going to return it to the Crusaders. However, these rumors turned out to be false.<ref>Sylvia Schein, "Gesta Dei per Mongolos"</ref> The general consensus of modern historians is that though Jerusalem may or may not have been subject to raids, that there was never any attempt by the Mongols to incorporate Jerusalem into their administrative system, which is what would be necessary to deem a territory "conquered" as opposed to "raided."<ref>Reuven Amitai, "Mongol raids into Palestine (1260 and 1300)</ref> |

||

==Mamluk rebuilding== |

|||

==Mamluk Ethnic Cleansing and Environmental Degradation== |

|||

To deter the Christians from recapturing the Holy Land, the Mamluks began a policy of ethnically and environmentally destroying the area. The Mamluks, destroyed most of the castles and fortifications within their control, destroyed the walls and their foundations of Jerusalem, and expelled the populations of the towns and cities. The final desertification of Palestine dates from this period. Nonetheless, the Mamluks were impressed by Jerusalem's religious states and undoubtedly were fearful of renewing further Crusades. Thus, the cities population was left unmolested. |

|||

| ⚫ | , pilgrims continued to come in small numbers. Pope [[Nicholas IV]] negotiated an agreement with the Mamluk sultan to allow Latin clergy to serve in the [[Church of the Holy Sepulchre]]. With the Sultan's agreement, Pope Nicholas, a [[Franciscan]] himself, sent a group of friars to keep the Latin liturgy going in Jerusalem. With the city little more than a backwater, they had no formal quarters, and simply lived in a pilgrim hostel, until in 1300 King [[Robert of Sicily]] gave a large gift of money to the Sultan. Robert asked that the Franciscans be allowed to have the [[Sion Church]], the Mary Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre, and the [[Church of the Nativity|Nativity Cave]], and the Sultan gave his permission. But the remainder of the Christian holy places kept in decay. <ref name=armstrong-307>Armstrong, pp. 307-308</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Mamluk sultans made a point of visiting the city, endowing new buildings, encouraging Muslim settlement, and expanding mosques. During the reign of Sultan [[Baibars]], the Mamluks renewed the Moslem alliance with the Jews and he established two new sanctuaries, one to [[Moses]] and one to [[Salih]], to encourage numerous Muslim and Jewish pilgrims to be in the area at the same time as the Christians, who filled the city during [[Easter]].<ref>Anderson, pp. 304-305</ref> In [[1267]] [[Nahmanides]] (also known as Ramban) made aliyah. In the Old City he established the [[Ramban Synagogue]], the oldest active synagogue in Jerusalem. However, the city had no great political power, and was in fact considered by the Mamluks as a place of exile for out-of-favor officials. The city itself was ruled by a low-ranking [[emir]].<ref>Armstrong, p. 310</ref> |

||

==Mamluk Jihad and Final Genocide== |

|||

Meanwhile, the Mamluks under [[Baibars Jihad]] slowly encircled the Christian principalities. Formenting division, provoking responses, and laying overwhelming siege piecemel to the remaining independent Christian cities. Ashkelon, Ceasaria, Tripolis, Beriut, one by one were encircled by hundreds of thousands of fanatical Mameluks and captured. In [[1291]], the Mamluks achieved decisive victories over the Crusaders, taking Jaffa and a number of strategically important castles and finally encircling the Christian's last major outpost on the Holy Land, the city of [[Acre]]. |

|||

Baibars had already died, but his Jihad was continued by the new Sultan. However, each new siege had grown more costly, as the fortifications increased from small towns and castles to the larger cities and Christian defense became more fanatical and indomitable. This last siege was to prove the most costly. Over half of the Mamluk army died in the siege included two sultans, three of armies commanders, and most of the officer corps. The final Mamluk commander was personally killed by the Templar Master of the city and the second sultan disappeared in fighting with the Christians in other parts of the city. Under the Crusader's fanatical defense much of the Christian population of the coasts were evacuated and nearly half of Acre's 200,000 Christian population was evacuated. However, those who didn't escape were killed or enslaved with so many Europeans that a woman of sex-slave category couldn't be bought for more than 1/1000 of an ounce of gold. |

|||

==Last Crusader Events and Jerusalem Decay== |

|||

Crusader-Mongol raids were also launched in 1300, including a destructive reprisal campaign for the loss of Acre which saw the capture and sacking of Alexandria, the burning of towns and farms in the delta, and a general campaign to obliterate the remaining Muslim villages near the coasts. There was also extensive rumors in Europe that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and were preparing to return it to the Christians. Whether these rumors were true is unknown as there is still debate among historians as to whether or not Mongol raids actually penetrated the city. It is known that Mongol raids reached as far south as [[Gaza]], while they were pursuing the retreating Mamluks and the Crusaders were laying siege to Jerusalem. But because there was minimal literary representation it is uknown as to the full events.<ref>Demurger, p.142 "The Mongols pursued the retreating troops towards the south, but stopped at the level of Gaza"</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Image:JacquesMolayPrendJerusalem1299VersaillesMuseeNationalChateauEtTrianons.jpg|thumb|"[[Jacques de Molay|Jacques Molay]] takes Jerusalem, 1299", a fanciful painting created in the 1800s by Claude Jacquand, and hanging in the "Hall of Crusades" in Versailles. In reality, though the Mongols may have been technically in control of the city for a few months in early 1300 (since the Mamluks had temporarily retreated to Cairo and no other troops were in the area), De Molay was almost certainly on the island of [[Cyprus]] at that time, nowhere near the landlocked city of Jerusalem.]] |

||

Though most modern historians state that Jerusalem was not captured in 1299/1300,<ref>Demurger, p.278-279</ref> the story of this alleged capture of Jerusalem was retold by historians during the following centuries, and even expanded in the 19th century to claims that Jerusalem was taken not by Mongols, but by [[Jacques de Molay]], [[Grand Master (order)|Grand Master]] of the [[Knights Templar]]. In 1805, the French historian/playwright Raynouard said, "In 1299, the Grand-Master was with his knights at the taking of Jerusalem."<ref name=raynouard>"Le grand-maître s'etait trouvé avec ses chevaliers en 1299 à la reprise de Jerusalem." {{cite web|author=François Raynouard|title= Précis sur les Templiers|date=1805|url=http://www.mediterranees.net/moyen_age/templiers/raynouard/precis.html}}</ref> The story was also expanded to say that Jacques de Molay had actually been placed in charge of one of the Mongol divisions. According to Demurger in ''The Last Templar'', this may have been because the medieval historian [[Templar of Tyre]] referred to a Mongol general named Mulay.<ref>Le Templier de Tyr mentions that one of the generals of Ghazan was named Molay, whom he left in Damas with 10,000 Mongols - "611. Ghazan, we he had vanquished the Sarazins returned in his country, and left in Damas one of his Admirals, who was named Molay, who had with him 10,000 Tatars and 4 general."611. Cacan quant il eut desconfit les Sarazins se retorna en son pais et laissa a Domas .i. sien amiraill en son leuc quy ot a nom Molay qui ot o luy .xm. Tatars et .iiii. amiraus.", but it is thought that this could instead designate a Mongol general "Mûlay". - Demurger, p.279</ref> In the 1861 edition of the French encyclopedia, the ''Nouvelle Biographie Universelle'', it says in the "Molay" article: |

|||

{{quote|"Jacques de Molay was not inactive in this decision of the Great Khan. This is proven by the fact that Molay was in command of one of the wings of the Mongol army. With the troops under his control, he invaded Syria, participated in the first battle in which the Sultan was vanquished, pursued the routed Malik Nasir as far as the desert of Egypt: then, under the guidance of Kutluk, a Mongol general, he was able to take Jerusalem, among other cities, over the Muslims, and the Mongols entered to celebrate Easter"|''Nouvelle Biographie Universelle'', "Molay" article, 1861.<ref>Demurger, p. 279</ref>}} <!-- Interesting, but please add the exact French in the footnote? --> |

|||

There is even a painting, ''Molay Prend Jerusalem, 1299'' ("Molay Takes Jerusalem, 1299"), hanging in the French national museum in [[Musée national du château de Versailles et des Trianons|Versailles]], created in 1846 by Claude Jacquand,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/joconde_fr?ACTION=RETROUVER&FIELD_98=REPR&VALUE_98=Molay%20Jacques&NUMBER=2&GRP=0&REQ=%28%28Molay%20Jacques%29%20%3aREPR%20%29&USRNAME=nobody&USRPWD=4%24%2534P&SPEC=1&SYN=1&IMLY=&MAX1=1&MAX2=250&MAX3=250&DOM=All|accessdate=2007-09-09|title=Jacques Molay Prend Jerusalem.1299|date=1846|author=Claudius Jacquand|format=painting|work=Hall of Crusades, Versailles}}</ref> which depicts the supposed event in 1299. However, De Molay was certainly nowhere near Jerusalem at the time.<ref>"He was seldom on the field: in Armenia in 1298 or 1299 maybe, at Ruad in november 1300 surely, but probably not in the naval operations of July-August 1300 in Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa. If the planned 1301 offensive of the Mongols had occurred, he would have been at the head of his troops in combat." Demurger, p. 159</ref> |

|||

In sum, the Christians and their Crusader protectors were forced to retreat to the island of Cyprus, and though it is clear they made coastal raids and even some large scale expeditions in conjunction with Mongol advances including a temporary recapture of Jerusalem in 1301 and spent centuries planning future all European Crusades, these actions never materialized or cemented into something permanent. What is clear is that in keeping with their genocidal and ethnic cleansing plans, the Mamluks had the Christian cities levelled, the farms destroyed, and the Holy Land was turned into a desert. Jerusalem decayed into an isolated town, and the foundations of the ancient cities of Philistia, Judea, Phoenocia, Isreal, Greco-Roman Levant, and the Crusades became temporary abodes for grazers and bandits. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Ottomans== |

==Ottomans== |

||

Revision as of 17:32, 17 March 2008

The history of the city of Jerusalem in the Middle Ages takes it from the 900s when it was under the rule of the Fatimid caliphate, to the Crusades and shifts in control brought by the Europeans, until the city was re-taken by the Khawarazmi Turks in 1244. The city then stayed under Muslim control for the next several hundred years, being passed back and forth through various Muslim factions, until decidedly conquered by the Ottomans in 1517, who maintained control until the British took it in 1917.

Byzantine rule

In the five centuries following the Bar Kokhba revolt, the city remained under Roman then Byzantine rule. During the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine I constructed Christian sites in Jerusalem such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Jerusalem reached a peak in size and population at the end of the Second Temple Period: The city covered two square kilometers (0.8 sq mi.) and had a population of 200,000[1][2] From the days of Constantine until the Arab conquest in 638, despite intensive lobbying by Judeo-Byzantines, Jews were forbidden to enter the city. Starting in 618, Byzantine chronicles state the Jews allied with the Moslems in their conquest of the Middle East. [3] Consequently, following the capture of Jerusalem and the slaughter of the Christian population and garrison in the citadel, the Jews were were allowed back into the city by Muslim rulers.[4] By the end of the 7th century, an Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik had commissioned and completed the construction of the Dome of the Rock over the Foundation Stone.[5] In the four hundred years that followed, Jerusalem's prominence diminished as Arab powers in the region jockeyed for control.[6]

Arab Caliphates (638-1300s)

Although the Qur'an does not mention the name "Jerusalem", the hadith specify that it was from Jerusalem that Muhammad ascended to heaven in the Night Journey, or Isra and Miraj. The city was one of the Arab Caliphate's first conquests in 638 CE; according to Arab historians of the time, the Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab personally went to the city to receive its submission, slaughtered the garrison and population who had fled to the citadel, and personally oversaw its cleaning out and founding the Temple Mount on it's ruins were he started the prayers of the new mosque. Sixty years later the Dome of the Rock was completed, a structure enshrining a stone from which Muhammad is said to have ascended to heaven during the Isra. (Note that the octagonal and gold-sheeted Dome is not the same thing as the Al-Aqsa Mosque beside it which was built more than three centuries later). For their aid in the capture of Jerusalem and the Middle East, Umar ibn al-Khattab also allowed the Jews back into the city and freedom to live and worship after four hundred years.

Under the early centuries of Muslim rule, especially during the Umayyad (650-750) and Abbasid (750-969) dynasties, the city prospered; the geographers Ibn Hawqal and al-Istakhri (10th century) describe it as "the most fertile province of Palestine", while its native son the geographer al-Muqaddasi (born 946) devoted many pages to its praises in his most famous work, The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Climes. Jerusalem under Muslim rule did not achieve the political or cultural status enjoyed by the capitals Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo etc. Interestingly, al-Muqaddasi derives his name from the Arabic name for Jerusalem, Bayt al-Muqaddas, which is linguistically equivalent to the Hebrew Beit Ha-Mikdash, the Jewish Temple.

Although they were severely discriminated and regulated in worship, movement, ownership of property, reparing of buildings etc, the early Arab period tolerated the presence of Christian and Jewish communities in the city with the Jewish population given the most freedom and benefices. However, the communities, especially the Christians were in essence second class citizens, forbidden to proslytize, worship outside of specific locations, limited in areas where they could travel, forced to bow before Muslim Mosques and Imams, charged to wear specific clothing, ordered to make way on the streets to Muslims, and limited in the number of pilgrims allowed to visit Holy sites. The Emperor Charlamagne started the precedent of Western European influence in the region under various treaties with the Caliphs establishing Frankish protection for pilgrims.

With the decline of the Carolonian Empire in the early 10th century, another period of persecution by the Muslims began. However, the recovered Byzantines filled this void and as the Empire expanded under the Byzantine Crusades, Christians were again allowed to pilgrimage to Jersualem. However, as the Byzantine borders expanded into the Levant in the early 11th century, the limited tolerance of the Muslim rulers toward Christians in the Middle East, started to end. The Egyptian Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of all churches throughout Al-Islam starting with the churches in Jerusalem. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, revered by most Christians as the site of Christ's crucifixion and burial, was among the places of worship destroyed. Reports of this, renewed killing of Christian pilgrims, and the defeat of Byzantium during the Seljuq Jihad were one cause of the First Crusade, which marched off from Europe to the area, and, on July 15, 1099, Christian soldiers took Jerusalem after a difficult one month siege. In keeping with their alliance with the Moslems, the Jews were among the most vigorous defenders of Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, the Crusaders gathered the Jews in a synagogue and burned them.

Crusader control

In 1099, Jerusalem was besieged by the First Crusaders, who killed most of its Muslim and Jewish inhabitants, apart from many Christians.[7] That would be the first of several conquests to take place over the next four hundred years.

Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a feudal state, of which the King of Jerusalem was the chief. Christian settlers from the West set about rebuilding the principal shrines associated with the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was ambitiously rebuilt as a great Romanesque church, and Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount (the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque) were converted for Christian purposes. It is during this period of Frankish occupation that the Military Orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar have their beginnings. Both grew out of the need to protect and care for the great influx of pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem in the twelfth century especially since Bedouin enslavement raids and terror attacks upon the roads by the remaining Muslim population continued. Under the the Kingdom of Jerusalem the area experienced a great revival, including the re-establishment of the city and harbour of Ceasaria, the restoration and fortification of the city of Tiberias, the expansion of the city of Ashkelan, the walling and rebuilding of Jaffa, the reconstruction of Betheleham, the repopulation of dozens of towns, the restoration of large agriculture, and the construction of hundreds of churches, cathedrals, and castles. However, this period of prosperity and peace was short and lasted until Saladin's Jihad succeeded in retaking Jerusalem itself in 1187. Saladin had planned on exterminating the entire population of the city but it's vigorous defense forced him to concedede in letting the population escape under terms. Following this the armies of Saladin conquered, expelled, enslaved, or killed the remaining Christian communities at Galillea, Judea, Samaria, as well as the towns of Ashkelon, Jaffa, Ceasaria, and Acre. (see Siege of Jerusalem (1187)).

According to Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, German Jews lived in Jerusalem during the 11th century. The story is told that a German-speaking Palestinian Jew saved the life of a young German man surnamed Dolberger. So when the knights of the First Crusade came to siege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger’s family members who was among them rescued Jews in Palestine and carried them back to Worms to repay the favor.[8] Further evidence of German communities in the holy city comes in the form of halakic questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the eleventh century.[9]

In 1173 Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem. He described it as a small city full of Jacobites, Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians. Two hundred Jews dwelt in a corner of the city under the Tower of David.

In 1187, the city was taken from the Crusaders by Saladin.[10]

In 1219 the walls of the city were razed by order of al-Mu'azzam, the Ayyubid sultan of Damascus. This rendered Jerusalem defenseless and dealt a heavy blow to the city's status.

Following another Crusade by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II started in 1222, it was surrendered by Saladin's descendant al-Kamil Between 1228 and 1244, it remained under Christian control. Under the terms of the treaty, with Egypt's ruler al-Kamil, Jerusalem came cirecty into the hands of Frederick II of Germany for a period of ten years. During this time, no walls or fortifications in the city or the strip which united it with the coast was allowed to be built. The people and nobility of the Kindgom were furious with the result feeling that the overwhelming power of the Emperor would have enabled much more successful terms under war. Additionally, the city was in effect a personal estate of the Emperor, leaving the nobility without any representation. In 1239, after a ten-year truce expired, Frederick ordered the rebuilding of the walls, but without the formidable Crusader army he had originally employed ten years previous, his goals were effectively thrawted when were again demolished by an-Nasir Da'ud, the emir of Kerak, in the same year.

In 1243 Jerusalem was firmly secured into the power of the Christian Kingdom, and the walls were repaired.

However, the period was extremely brief as a large army of Turkish and Persian Moslems was advancing from the north.

Khwarezmian control

Jerusalem fell again in 1244 to the Khawarezmi Turks, who had been displaced by the advance of the Mongols. As the Khwarezmians moved west, they allied with the Egyptians, under the Egyptian Ayyubid Sultan al-Malik al-Salih. He recruited his horsemen from the Khwarezmians, and directed the remains of the Khwarezmian Empire into Palestine and Syria, where he wanted to organize a strong defense against the Mongols. In keeping with his goal, the main effect of the Khwarezmians was to slaughter the local population, especially in Jerusalem. They invaded the city on July 11, 1244, and the city's citadel, the Tower of David, surrendered on August 23.[11] The Khwarezmians then ruthlessly decimated the population, leaving only 2,000 people, Christians and Muslims, still living in the city.[12] This attack triggered the Europeans to respond with the Seventh Crusade, although the new forces of King Louis never even achieved success in Egypt, let alone advancing as far as Palestine.

Ayyubid control

After his troubles with the Khwarezmians, the Muslim Sultan Al-Salih then began ordering armed expeditions to raid into Christian communities and capture men, women and children. Called riazzas, the raids extended into Caucasia, the Black Sea, Byzantium, and the coastal areas of Europe. The newly enslaved were divided according to category. Women were either turned into maids or sex slaves. The men depending upon age and ability were made into servants or killed. Young boys and girls were sent to Imams were they were indoctrinated into Islam. According to ability the young boys were then made into eunichs or sent into decades long training as slave soldiers for the sultan. Called Mamluks, this army of brainwashed, indocrinated enslaved Christian Europeans were forged into a potent armed force which combined the innate strength and prowess of the Europeans with fanatical indoctrinated submission to Islam and the Sultan. He then used his new Mamluk army to eliminate the Khwarezmians, and Jerusalem returned to Egyptian Ayyubid rule in 1247.

Mamluk control and Mongol raids

When al-Salih died, his widow, the slave Shajar al-Durr, took power as Sultana, which power she then transferred to the Mamluk leader Aybeg, who became Sultan in 1250.[13] Meanwhile, the Christian rulers of Antioch and Cilician Armenia subjected their territories to Mongol authority, and fought alongside the Mongols during the Empire's expansion into Iraq and Syria. In 1260, a portion of the Mongol army advanced toward Egypt, and was engaged by the Mamluks in Galilee, at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut. The Mamluks were victorious, and the Mongols left the area. In early 1300, there were again some Mongol raids into Palestine, shortly after the Mongols had been successful in capturing cities in northern Syria; however, the Mongols occupied the area for only a few weeks, and then retreated again to Iran. The Mamluks regrouped and re-asserted control over Palestine a few months later, with little resistance.

There is little evidence to indicate whether or not the Mongol raids penetrated Jerusalem in either 1260 or 1300. Historical reports from the time period tend to conflict, depending on which nationality of historian was writing the report. There were also a large number of rumors and urban legends in Europe, that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and were going to return it to the Crusaders. However, these rumors turned out to be false.[14] The general consensus of modern historians is that though Jerusalem may or may not have been subject to raids, that there was never any attempt by the Mongols to incorporate Jerusalem into their administrative system, which is what would be necessary to deem a territory "conquered" as opposed to "raided."[15]

Mamluk rebuilding

Even during the conflict, pilgrims continued to come in small numbers. Pope Nicholas IV negotiated an agreement with the Mamluk sultan to allow Latin clergy to serve in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. With the Sultan's agreement, Pope Nicholas, a Franciscan himself, sent a group of friars to keep the Latin liturgy going in Jerusalem. With the city little more than a backwater, they had no formal quarters, and simply lived in a pilgrim hostel, until in 1300 King Robert of Sicily gave a large gift of money to the Sultan. Robert asked that the Franciscans be allowed to have the Sion Church, the Mary Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre, and the Nativity Cave, and the Sultan gave his permission. But the remainder of the Christian holy places were kept in decay. [16]

Mamluk sultans made a point of visiting the city, endowing new buildings, encouraging Muslim settlement, and expanding mosques. During the reign of Sultan Baibars, the Mamluks renewed the Moslem alliance with the Jews and he established two new sanctuaries, one to Moses and one to Salih, to encourage numerous Muslim and Jewish pilgrims to be in the area at the same time as the Christians, who filled the city during Easter.[17] In 1267 Nahmanides (also known as Ramban) made aliyah. In the Old City he established the Ramban Synagogue, the oldest active synagogue in Jerusalem. However, the city had no great political power, and was in fact considered by the Mamluks as a place of exile for out-of-favor officials. The city itself was ruled by a low-ranking emir.[18]

Ottomans

In 1517, Jerusalem and its environs fell to the Ottoman Turks, who would maintain control of the city until the 20th century.[10] Although the European population had been obliterated from the Holy Land or in the wars retreated into the hills were they intermarried with other communities, Christian presence including Europeans remained in Jerusalem. During the Ottomans this presence increased as Greeks under Turkish Sultan patronage re-established, restored, or reconstructed Orthodox Churches, Hospitals, and communities. Armenians and Georgians fleeing Turkish pograms also joined the small community of European Christian. This era saw the first expansion outside the Old City walls, as new neighborhoods were established to relieve the overcrowding that had become so prevalent. The first of these new neighborhoods included the Russian Compound and the Jewish Mishkenot Sha'ananim, both founded in 1860. For most of the period, Jeruslam remained a Christian dominated city. [19]

Notes

- ^ Har-el, Menashe. This Is Jerusalem. Canaan Publishing House.

{{cite book}}: Text "1977" ignored (help); Text "pages68–95" ignored (help) - ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (2007-02-22). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Zank, Michael. "Byzantian Jerusalem". Boston University. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0521599849.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hoppe, Leslie J. (2000). The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament. Michael Glazier Books. p. 15. ISBN 0814650813.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zank, Michael. "Abbasid Period and Fatimid Rule (750–1099)". Boston University. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ Hull, Michael D. (1999). "First Crusade: Siege of Jerusalem". Military History. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Seder ha-Dorot", p. 252, 1878 ed.

- ^ Epstein, in "Monatsschrift," xlvii. 344; Jerusalem: Under the Arabs

- ^ a b "Main Events in the History of Jerusalem". Jerusalem: The Endless Crusade. The CenturyOne Foundation. 2003. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades, p. 191

- ^ Armstrong, p.304

- ^ Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages, 1250-1520, p. 264

- ^ Sylvia Schein, "Gesta Dei per Mongolos"

- ^ Reuven Amitai, "Mongol raids into Palestine (1260 and 1300)

- ^ Armstrong, pp. 307-308

- ^ Anderson, pp. 304-305

- ^ Armstrong, p. 310

- ^ Elyon, Lili (1999). "Jerusalem: Architecture in the Late Ottoman Period". Focus on Israel. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

References

- Armstrong, Karen (1996). Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. Random House. ISBN 0-679-43596-4.

- Demurger, Alain (2007). Jacques de Molay (in French). Editions Payot&Rivages. ISBN 2228902357.

- Hazard, Harry W. (editor) (1975). Volume III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. A History of the Crusades. Kenneth M. Setton, general editor. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0582368965.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4.

- Newman, Sharan (2006). Real History Behind the Templars. Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-425-21533-3.

- Nicolle, David (2001). The Crusades. Essential Histories. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-179-4.

- Richard, Jean (1996). Histoire des Croisades. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59787-1.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1987, 2005). The Crusades: A History (2nd edition ed.). Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-10128-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2002). The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192803123.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Runciman, Steven (1987 (first published in 1952-1954)). A history of the Crusades 3. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140137057.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event". The English Historical Review. 94 (373): 805–819.

- Schein, Sylvia (1991). Fideles Crucis: The Papacy, the West, and the Recovery of the Holy Land. Clarendon. ISBN 0198221657.

- Schein, Sylvia (2005). Gateway to the Heavenly City: crusader Jerusalem and the catholic West. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 075460649X.

- Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1).