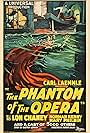

A mad, disfigured composer seeks love with a lovely young opera singer.A mad, disfigured composer seeks love with a lovely young opera singer.A mad, disfigured composer seeks love with a lovely young opera singer.

- Awards

- 4 wins & 1 nomination

John St. Polis

- Comte Philip de Chagny

- (as John Sainpolis)

Virginia Pearson

- Carlotta

- (1929 re-edited version)

- …

Olive Ann Alcorn

- La Sorelli

- (uncredited)

Betty Allen

- Ballerina

- (uncredited)

Betty Arthur

- Ballet Dancer

- (uncredited)

Joseph Belmont

- Stage Manager

- (uncredited)

Alexander Bevani

- Mephistopheles

- (uncredited)

Earl Gordon Bostwick

- Minor Role

- (uncredited)

Ethel Broadhurst

- Frightened Ballerina

- (uncredited)

Edward Cecil

- Faust

- (uncredited)

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaLon Chaney's horrific, self-applied makeup was kept secret right up until the film's premiere. Not a single photograph of Chaney as The Phantom was published in a newspaper or magazine or seen anywhere before the film opened in theaters. Universal Pictures wanted The Phantom's face to be a complete surprise when his mask was ripped off.

- Goofs(1929 cut) When the Phantom's alarm goes off, the sound of the chimes does not always match the striking of the device's "arms". That is because what is heard is the film's soundtrack, not "sound effects", which do not exist in a silent film. As such, this being "off sync" is allowable.

- Quotes

The Phantom: [Christine sees a casket in the room] That is where I sleep. It keeps me reminded of that other dreamless sleep that cures all ills - forever!

Christine Daae: You - You are the Phantom!

The Phantom: If I am the Phantom, it is because man's hatred has made me so. If I shall be saved, it will be because your love redeems me.

- Crazy creditsIn 1925 (and for many years afterwards), credits used to appear at the beginning of movies. In this film, the credits do appear at the beginning but also are repeated at the end, preceded by the following caption: "This is repeated at the request of picture patrons who desire to check the names of performers whose work has pleased them."

- Alternate versionsIn 2012 it was determined that an "accidental 3-D" version of the film existed. From an examination of various prints of the film, it was discovered that most - if not all - of the original film was shot using two cameras placed side-by-side. This was most likely done to create simultaneous master and safety/domestic and foreign negatives of the film. However, when synched together and anaglyph color-tinted, the spatial distance between the two simultaneous film strips translates into an effective 3-D film. Under the working title of LA FANTOME 3D, a fund-raising effort is under way to locate and restore (create) a full "accidental 3-D" version of the film.

- ConnectionsEdited into Drácula (1931)

Featured review

I find silent films more eerie than the talking B&W horror films (Dracula, Frankenstien, the Thing from Another World) and also more eerie than the modern color films (Suspiria, Ju-on, the Descent). The exaggeration in the actors gestures and expressions; the early camera technology that's not quite fluid and not quite clear; the tinted colors; and an artificially overlaid soundtrack it all combines and adds up to paint an abstract and unnatural picture.

Cinema has evolved so far since the Silent Era that watching these films is almost like glimpsing into another world completely unrelated to the one most of us grew up watching. And I find it fascinating that this is, indeed, the ancestor to many horror films that I adore today. So, like with other classics, I viewed Phantom of the Opera with the delight of discovering our cinematic horror roots seeing the predecessor to Jack Pierce, Rick Baker, and Stan Winston in action, watching the precursor to John Carpenter, Mario Bava, and David Cronenberg.

From the opening scene, Phantom of the Opera makes great use of shadows. A character with a lantern wanders the labyrinth below the Paris Opera house, ducking into an alcove as the shadow of the Phantom passes. Barring a handful of shots showing a cloaked figure from behind (or from a distance), this motif continues as Erik, the Phantom, is represented as a shadow, calling to Christine from the catacombs behind her dressing room mirror until she inevitably comes face to face with the mask (which she will inevitably remove.) Even though I'm quite familiar with the face of Lon Chaney's Phantom from the numerous still-shots out there, I still felt the pulse of anxiety and suspense when that famous moment drew near. Though blatantly exploitive in its camera angle, the timing, the expression on Chaney's face, though it aims purely for spectacle and shock for the audience of 1925, it carries something newer spectacles/shock-films lack: charm.

I couldn't help but smile watching Chaney's haunting performance beneath that famous makeup, seeing it animated for the first time, the sadness and tragedy that underlines the phantoms soul. He moves with a precision and deliberateness that's not entirely natural, but remains paradoxically sincere. The rooftop scene, in particular, where Christine and Raoul plot, oblivious to the presence of the unmasked phantom who listens in with great intensity from his perch above gripping his cape in his heartbroken state, eventually throwing himself back into the grasp of the statue in disbelieving defeat.

There's something both awkward and poetic to the movements of the actors as they express their emotions not in subtleties, but rather in exaggerated body language that almost feels at home here (almost, but not quite.) Early in the film, frightened ballerinas spontaneously spin in place (one revolution) as a visual representation of their anxiety. Somewhat silly, but simultaneously delightful in its approach.

Later in the film, Christine rejects the Phantom, arcing her back to its limit, her face turned as far away as possible, with her hands outstretched as if the very air around Erik would prove toxic. A single still frame presented to an audience, completely isolated from the context of the rest of the film, would leave absolutely no room for misinterpretations.

The film goes on to a larger scope and bigger thrills with the inevitable fall of the chandelier, the Phantom's many tricks and traps in the catacombs under the Paris Opera House, and the final pursuit where the mob chases Erik through the streets of Paris -- the film strains itself to outdo all the silent films that came before. However, it strains too far, and I find myself liking the film in its quieter, more personal, exploits (the phantom in the shadows, the unmasking, the rooftop.) I do have to comment on the end of the film, though: Erik has been cornered and surrounded on all sides by the angry mob. He raises up a closed fist threateningly, as though within his grasp lay one final card that could level the playing field -- an explosive of some type -- and the crowd visibly hesitates, backing off. After a dramatic pause, the Phantom opens his hand to reveal he's holding nothing at all.

Then we realize the film, itself, has done the very same thing. For the length of its running time it convinces you it held something -- some kind of awe-inspiring trick up its sleeve. Thus the problem with all exploitation films, but you have to admire Phantom for how it sustains so little for so long and makes you smile after you realize the truth.

Like a good magic trick.

Cinema has evolved so far since the Silent Era that watching these films is almost like glimpsing into another world completely unrelated to the one most of us grew up watching. And I find it fascinating that this is, indeed, the ancestor to many horror films that I adore today. So, like with other classics, I viewed Phantom of the Opera with the delight of discovering our cinematic horror roots seeing the predecessor to Jack Pierce, Rick Baker, and Stan Winston in action, watching the precursor to John Carpenter, Mario Bava, and David Cronenberg.

From the opening scene, Phantom of the Opera makes great use of shadows. A character with a lantern wanders the labyrinth below the Paris Opera house, ducking into an alcove as the shadow of the Phantom passes. Barring a handful of shots showing a cloaked figure from behind (or from a distance), this motif continues as Erik, the Phantom, is represented as a shadow, calling to Christine from the catacombs behind her dressing room mirror until she inevitably comes face to face with the mask (which she will inevitably remove.) Even though I'm quite familiar with the face of Lon Chaney's Phantom from the numerous still-shots out there, I still felt the pulse of anxiety and suspense when that famous moment drew near. Though blatantly exploitive in its camera angle, the timing, the expression on Chaney's face, though it aims purely for spectacle and shock for the audience of 1925, it carries something newer spectacles/shock-films lack: charm.

I couldn't help but smile watching Chaney's haunting performance beneath that famous makeup, seeing it animated for the first time, the sadness and tragedy that underlines the phantoms soul. He moves with a precision and deliberateness that's not entirely natural, but remains paradoxically sincere. The rooftop scene, in particular, where Christine and Raoul plot, oblivious to the presence of the unmasked phantom who listens in with great intensity from his perch above gripping his cape in his heartbroken state, eventually throwing himself back into the grasp of the statue in disbelieving defeat.

There's something both awkward and poetic to the movements of the actors as they express their emotions not in subtleties, but rather in exaggerated body language that almost feels at home here (almost, but not quite.) Early in the film, frightened ballerinas spontaneously spin in place (one revolution) as a visual representation of their anxiety. Somewhat silly, but simultaneously delightful in its approach.

Later in the film, Christine rejects the Phantom, arcing her back to its limit, her face turned as far away as possible, with her hands outstretched as if the very air around Erik would prove toxic. A single still frame presented to an audience, completely isolated from the context of the rest of the film, would leave absolutely no room for misinterpretations.

The film goes on to a larger scope and bigger thrills with the inevitable fall of the chandelier, the Phantom's many tricks and traps in the catacombs under the Paris Opera House, and the final pursuit where the mob chases Erik through the streets of Paris -- the film strains itself to outdo all the silent films that came before. However, it strains too far, and I find myself liking the film in its quieter, more personal, exploits (the phantom in the shadows, the unmasking, the rooftop.) I do have to comment on the end of the film, though: Erik has been cornered and surrounded on all sides by the angry mob. He raises up a closed fist threateningly, as though within his grasp lay one final card that could level the playing field -- an explosive of some type -- and the crowd visibly hesitates, backing off. After a dramatic pause, the Phantom opens his hand to reveal he's holding nothing at all.

Then we realize the film, itself, has done the very same thing. For the length of its running time it convinces you it held something -- some kind of awe-inspiring trick up its sleeve. Thus the problem with all exploitation films, but you have to admire Phantom for how it sustains so little for so long and makes you smile after you realize the truth.

Like a good magic trick.

- jaywolfenstien

- Sep 21, 2006

- Permalink

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Language

- Also known as

- Phantom of the Opera

- Filming locations

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $3,751,476

- Gross worldwide

- $4,360,000

- Runtime1 hour 33 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was The Phantom of the Opera (1925) officially released in India in English?

Answer