Neurotransmitter: Difference between revisions

HiYahhFriend (talk | contribs) moved last addition to different location |

HiYahhFriend (talk | contribs) →Actions: Added vital info to section 'Actions' |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Some neurotransmitters are commonly described as "excitatory" or "inhibitory". The only direct effect of a neurotransmitter is to activate one or more types of receptors. The effect on the postsynaptic cell depends, therefore, entirely on the properties of those receptors. It happens that for some neurotransmitters (for example, glutamate), the most important receptors all have excitatory effects: that is, they increase the probability that the target cell will fire an action potential. For other neurotransmitters, such as GABA, the most important receptors all have inhibitory effects (although there is [[Gamma-Aminobutyric acid#Brain development|evidence that GABA is excitatory]] during early brain development). There are, however, other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, for which both excitatory and inhibitory receptors exist; and there are some types of receptors that activate complex metabolic pathways in the postsynaptic cell to produce effects that cannot appropriately be called either excitatory or inhibitory. Thus, it is an oversimplification to call a neurotransmitter excitatory or inhibitory—nevertheless it is convenient to call glutamate excitatory and GABA inhibitory so this usage is seen frequently. |

Some neurotransmitters are commonly described as "excitatory" or "inhibitory". The only direct effect of a neurotransmitter is to activate one or more types of receptors. The effect on the postsynaptic cell depends, therefore, entirely on the properties of those receptors. It happens that for some neurotransmitters (for example, glutamate), the most important receptors all have excitatory effects: that is, they increase the probability that the target cell will fire an action potential. For other neurotransmitters, such as GABA, the most important receptors all have inhibitory effects (although there is [[Gamma-Aminobutyric acid#Brain development|evidence that GABA is excitatory]] during early brain development). There are, however, other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, for which both excitatory and inhibitory receptors exist; and there are some types of receptors that activate complex metabolic pathways in the postsynaptic cell to produce effects that cannot appropriately be called either excitatory or inhibitory. Thus, it is an oversimplification to call a neurotransmitter excitatory or inhibitory—nevertheless it is convenient to call glutamate excitatory and GABA inhibitory so this usage is seen frequently. |

||

==Actions== |

==Actions== |

||

{{Main|Neuromodulation}} |

{{Main|Neuromodulation}} |

||

As explained above, the only direct action of a neurotransmitter is to activate a receptor. Therefore, the effects of a neurotransmitter system depend on the connections of the neurons that use the transmitter, and the chemical properties of the receptors that the transmitter binds to. |

As explained above, the only direct action of a neurotransmitter is to activate a receptor. Therefore, the effects of a neurotransmitter system depend on the connections of the neurons that use the transmitter, and the chemical properties of the receptors that the transmitter binds to. |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

*[[Opioid peptides]] are neurotransmitters that act within pain pathways and the emotional centers of the brain; some of them are [[analgesic]]s and elicit pleasure or euphoria.<ref>Schacter, Gilbert and Weger. Psychology. 2009.Print.</ref> |

*[[Opioid peptides]] are neurotransmitters that act within pain pathways and the emotional centers of the brain; some of them are [[analgesic]]s and elicit pleasure or euphoria.<ref>Schacter, Gilbert and Weger. Psychology. 2009.Print.</ref> |

||

Neurons expressing certain types of neurotransmitters sometimes form distinct systems, where activation of the system affects large volumes of the brain, called [[volume transmission]]. Major neurotransmitter systems include the [[noradrenaline]] (norepinephrine) system, the [[dopamine]] system, the [[serotonin]] system and the [[cholinergic]] system. |

Neurons expressing certain types of neurotransmitters sometimes form distinct systems, where activation of the system affects large volumes of the brain, called [[volume transmission]]. Major neurotransmitter systems include the [[noradrenaline]] (norepinephrine) system, the [[dopamine]] system, the [[serotonin]] system and the [[cholinergic]] system. |

||

Drugs can influence an animal's behavior by altering neurotransmitter activity. For example, drugs can decrease the rate of synthesis of neurotransmitter by affecting the synthetic enzyme(s) for that neurotransmitter. When neurotransmitter synthesis is blocked, the amount of neurotransmitter available for release is lowered, resulting in a decrease in neurotransmitter activity. |

|||

| ⚫ | Drugs targeting the neurotransmitter of |

||

| ⚫ | Diseases may affect specific neurotransmitter systems. For example, [[Parkinson's disease]] is at least in part related to failure of dopaminergic cells in deep-[[brain nuclei]], for example the [[substantia nigra]]. [[L-DOPA|Levodopa]] is a precursor of dopamine, and is the most widely used drug to treat Parkinson's disease. |

||

A brief comparison of the major neurotransmitter systems follows: |

A brief comparison of the major neurotransmitter systems follows: |

||

| Line 111: | Line 105: | ||

| medial [[septal nucleus]] |

| medial [[septal nucleus]] |

||

|} |

|} |

||

===Drug effects=== |

|||

Drugs can influence an animal's behavior by altering neurotransmitter activity. For example, drugs can decrease the rate of synthesis of neurotransmitter by affecting the synthetic enzyme(s) for that neurotransmitter. When neurotransmitter synthesis is blocked, the amount of neurotransmitter available for release is lowered, resulting in a decrease in neurotransmitter activity. Some drugs block or stimulate the release of specific neurotransmitters. Alternatively, drugs can prevent neurotransmitter storage in synaptic vesicles by causing the synaptic vesicle membranes to leak. Drugs that prevent a neurotransmitter from binding to its receptor are called [[receptor antagonist]]s. For example, drugs used to treat patients with schizophrenia such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and clozapine are antagonists at receptors in the brain for dopamine. Other drugs act by binding to a receptor and mimicking the normal neurotransmitter. Such drugs are called receptor [[agonist]]s. An example of a receptor agonist is Valium, a benzodiazepine that mimics the effect of the endogenous neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to decrease anxiety. Other drugs interfere with the deactivation of a neurotransmitter after it has been released, thereby prolonging the action of a neurotransmitter. This can be accomplished by blocking reuptake or inhibiting degradative enzymes. Lastly, drugs can also prevent an action potential from occurring, blocking neuronal activity throughout the central and peripheral nervous system. Drugs such as tetrodotoxin that block neural activity are typically lethal. |

|||

| ⚫ | Drugs targeting the neurotransmitter of systems affect the whole system; this fact explains the complexity of action of some drugs. [[Cocaine]], for example, blocks the reuptake of [[dopamine]] back into the [[presynaptic]] neuron, leaving the neurotransmitter molecules in the [[synapse|synaptic gap]] longer. Since the dopamine remains in the synapse longer, the neurotransmitter continues to bind to the receptors on the [[postsynaptic]] neuron, eliciting a pleasurable emotional response. Physical addiction to cocaine may result from prolonged exposure to excess dopamine in the synapses, which leads to the [[downregulation]] of some postsynaptic receptors. After the effects of the drug wear off, one might feel depressed because of the decreased probability of the neurotransmitter binding to a receptor. [[Prozac]] is a [[serotonin reuptake inhibitor|selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor]] (SSRI), which blocks re-uptake of serotonin by the presynaptic cell. This increases the amount of serotonin present at the synapse and allows it to remain there longer, hence potentiating the effect of naturally released serotonin.<ref name="InhibitingSerotoninSynthesis">{{cite journal|author = Yadav, V. et al|title = Lrp5 Controls Bone Formation by Inhibiting Serotonin Synthesis in the Duodenum|journal = Cell|volume = 135|issue = 5|pages = 825–837|year = 2008|doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059|pmid = 19041748|pmc = 2614332|last2 = Ryu|first2 = Je-Hwang|last3 = Suda|first3 = Nina|last4 = Tanaka|first4 = Kenji F.|last5 = Gingrich|first5 = Jay A.|last6 = Schütz|first6 = Günther|last7 = Glorieux|first7 = Francis H.|last8 = Chiang|first8 = Cherie Y.|last9 = Zajac|first9 = Jeffrey D.|first10 = Karl L.|first11 = J. John|first12 = Rene|first13 = Patricia|first14 = Gerard}}</ref> [[AMPT]] prevents the conversion of tyrosine to [[L-DOPA]], the precursor to dopamine; [[reserpine]] prevents dopamine storage within [[Synaptic vesicle|vesicles]]; and [[deprenyl]] inhibits [[monoamine oxidase]] (MAO)-B and thus increases dopamine levels. |

||

| ⚫ | Diseases may affect specific neurotransmitter systems. For example, [[Parkinson's disease]] is at least in part related to failure of dopaminergic cells in deep-[[brain nuclei]], for example the [[substantia nigra]]. [[L-DOPA|Levodopa]] is a precursor of dopamine, and is the most widely used drug to treat Parkinson's disease. |

||

==Common neurotransmitters== |

==Common neurotransmitters== |

||

Revision as of 07:23, 22 February 2014

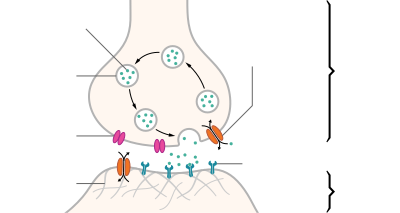

Neurotransmitters are endogenous chemicals that transmit signals across a synapse from one neuron (brain cell) to another 'target' neuron.[1] Neurotransmitters are packaged into synaptic vesicles clustered beneath the membrane in the axon terminal, on the presynaptic side of a synapse. Neurotransmitters are released into and diffuse across the synaptic cleft, where they bind to specific receptors in the membrane on the postsynaptic side of the synapse.[2] Many neurotransmitters are synthesized from plentiful and simple precursors, such as amino acids, which are readily available from the diet and which require only a small number of biosynthetic steps to convert.

Most neurotransmitters are about the size of a single amino acid, but some neurotransmitters may be the size of larger proteins or peptides. A neurotransmitter is available only briefly - before rapid deactivation - to bind to the postsynaptic receptors. Deactivation may occur due to: the removal of neurotransmitter by re-uptake into the presynaptic terminal; or degradative enzymes in the synaptic cleft. Nevertheless, short-term exposure of the receptor to neurotransmitter is typically sufficient for causing a postsynaptic response by way of synaptic transmission.

In response to a threshold action potential or graded electrical potential, a neurotransmitter is released at the presynaptic terminal. Low level "baseline" release also occurs without electrical stimulation. The released neurotransmitter may then move across the synapse to be detected by and bind with receptors in the postsynaptic neuron. Binding of neurotransmitters may influence the postsynaptic neuron in either an inhibitory or excitatory way. This neuron may be connected to many more neurons, and if the total of excitatory influences is greater than that of inhibitory influences, it will also "fire". That is to say, it will create a new action potential at its axon hillock to release neurotransmitters and pass on the information to yet another neighboring neuron.[3]

Discovery

Until the early 20th century, scientists assumed that the majority of synaptic communication in the brain was electrical. However, through the careful histological examinations of Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), a 20 to 40 nm gap between neurons, known today as the synaptic cleft, was discovered. The presence of such a gap suggested communication via chemical messengers traversing the synaptic cleft, and in 1921 German pharmacologist Otto Loewi (1873–1961) confirmed that neurons can communicate by releasing chemicals. Through a series of experiments involving the vagus nerves of frogs, Loewi was able to manually slow the heart rate of frogs by controlling the amount of saline solution present around the vagus nerve. Upon completion of this experiment, Loewi asserted that sympathetic regulation of cardiac function can be mediated through changes in chemical concentrations. Furthermore, Otto Loewi is accredited with discovering acetylcholine (ACh)—the first known neurotransmitter.[4] Some neurons do, however, communicate via electrical synapses through the use of gap junctions, which allow specific ions to pass directly from one cell to another.[5]

Neurons form elaborate networks through which nerve impulses (action potentials) travel. Each neuron has as many as 15,000 connections with other neurons. Neurons do not touch each other (except in the case of an electrical synapse through a gap junction); instead, neurons interact at contact points called synapses. A neuron transports its information by way of a nerve impulse. When a nerve impulse arrives at the synapse, it may release neurotransmitters, which influence another cell, either in an inhibitory or excitatory way. The next neuron may be connected to many more neurons, and if the total of excitatory influences is greater than that of inhibitory influences, it will also "fire". That is to say, it will create a new action potential at its axon hillock, releasing neurotransmitters and passing on the information to yet another neighboring neuron.

Identifying neurotransmitters

The chemical identity of neurotransmitters is often difficult to determine experimentally. For example, it is easy using an electron microscope to recognize vesicles on the presynaptic side of a synapse, but it may not be easy to determine directly what chemical is packed into them. The difficulties led to many historical controversies over whether a given chemical was or was not clearly established as a transmitter. In an effort to give some structure to the arguments, neurochemists worked out a set of experimentally tractable rules. According to the prevailing beliefs of the 1960s, a chemical can be classified as a neurotransmitter if it meets the following conditions:

- There are precursors and/or synthesis enzymes located in the presynaptic side of the synapse.

- The chemical is present in the presynaptic element.

- It is available in sufficient quantity in the presynaptic neuron to affect the postsynaptic neuron.

- There are postsynaptic receptors and the chemical is able to bind to them.

- A biochemical mechanism for inactivation is present.

Modern advances in pharmacology, genetics, and chemical neuroanatomy have greatly reduced the importance of these rules. A series of experiments that may have taken several years in the 1960s can now be done, with much better precision, in a few months. Thus, it is unusual nowadays for the identification of a chemical as a neurotransmitter to remain controversial for very long periods of time.

Types of neurotransmitters

There are many different ways to classify neurotransmitters. Dividing them into amino acids, peptides, and monoamines is sufficient for some classification purposes.

Major neurotransmitters:

- Amino acids: glutamate,[3] aspartate, D-serine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glycine

- Monoamines and other biogenic amines: dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (noradrenaline; NE, NA), epinephrine (adrenaline), histamine, serotonin (SE, 5-HT)

- Trace amines: phenethylamine, N-methylphenethylamine, tyramine, 3-iodothyronamine, Octopamine, tryptamine, N,N-Dimethyltryptamine

- Peptides: somatostatin, substance P, cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript, opioid peptides[6]

- Others: acetylcholine (ACh), adenosine, anandamide, nitric oxide, etc.

In addition, over 50 neuroactive peptides have been found, and new ones are discovered regularly. Many of these are "co-released" along with a small-molecule transmitter, but in some cases a peptide is the primary transmitter at a synapse. β-endorphin is a relatively well known example of a peptide neurotransmitter; it engages in highly specific interactions with opioid receptors in the central nervous system.

Single ions, such as synaptically released zinc, are also considered neurotransmitters by some,[7] as are some gaseous molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and carbon monoxide (CO).[8] Because they are not packaged into vesicles they are not classical neurotransmitters by the strictest definition, however they have all been shown experimentally to be released by presynaptic terminals in an activity-dependent way.

By far the most prevalent transmitter is glutamate, which is excitatory at well over 90% of the synapses in the human brain.[3] The next most prevalent is GABA, which is inhibitory at more than 90% of the synapses that do not use glutamate. Even though other transmitters are used in far fewer synapses, they may be very important functionally—the great majority of psychoactive drugs exert their effects by altering the actions of some neurotransmitter systems, often acting through transmitters other than glutamate or GABA. Addictive drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine exert their effects primarily on the dopamine system. The addictive opiate drugs exert their effects primarily as functional analogs of opioid peptides, which, in turn, regulate dopamine levels.

Excitatory and inhibitory

Some neurotransmitters are commonly described as "excitatory" or "inhibitory". The only direct effect of a neurotransmitter is to activate one or more types of receptors. The effect on the postsynaptic cell depends, therefore, entirely on the properties of those receptors. It happens that for some neurotransmitters (for example, glutamate), the most important receptors all have excitatory effects: that is, they increase the probability that the target cell will fire an action potential. For other neurotransmitters, such as GABA, the most important receptors all have inhibitory effects (although there is evidence that GABA is excitatory during early brain development). There are, however, other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, for which both excitatory and inhibitory receptors exist; and there are some types of receptors that activate complex metabolic pathways in the postsynaptic cell to produce effects that cannot appropriately be called either excitatory or inhibitory. Thus, it is an oversimplification to call a neurotransmitter excitatory or inhibitory—nevertheless it is convenient to call glutamate excitatory and GABA inhibitory so this usage is seen frequently.

Actions of neurotransmitters

As explained above, the only direct action of a neurotransmitter is to activate a receptor. Therefore, the effects of a neurotransmitter system depend on the connections of the neurons that use the transmitter, and the chemical properties of the receptors that the transmitter binds to.

Here are a few examples of important neurotransmitter actions:

- Glutamate is used at the great majority of fast excitatory synapses in the brain and spinal cord. It is also used at most synapses that are "modifiable", i.e. capable of increasing or decreasing in strength. Modifiable synapses are thought to be the main memory-storage elements in the brain. Excessive glutamate release can overstimulate the brain and lead to excitotoxicity causing cell death resulting in seizures or strokes.[9] Excitotoxicity has been implicated in certain chronic diseases including ischemic stroke, epilepsy, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington disease, and Parkinson's disease[10]

- GABA is used at the great majority of fast inhibitory synapses in virtually every part of the brain. Many sedative/tranquilizing drugs act by enhancing the effects of GABA.[11] Correspondingly, glycine is the inhibitory transmitter in the spinal cord.

- Acetylcholine is distinguished as the transmitter at the neuromuscular junction connecting motor nerves to muscles. The paralytic arrow-poison curare acts by blocking transmission at these synapses. Acetylcholine also operates in many regions of the brain, but using different types of receptors, including nicotinic and muscarinic receptors.[12]

- Dopamine has a number of important functions in the brain; this includes regulation of motor behavior, pleasures related to motivation and also emotional arousal. It plays a critical role in the reward system; people with Parkinson's disease have been linked to low levels of dopamine and people with schizophrenia have been linked to high levels of dopamine.[13]

- Serotonin is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Most is produced by and found in the intestine (approximately 90%), and the remainder in central nervous system neurons. It functions to regulate appetite, sleep, memory and learning, temperature, mood, behaviour, muscle contraction, and function of the cardiovascular system and endocrine system. It is speculated to have a role in depression, as some depressed patients are seen to have lower concentrations of metabolites of serotonin in their cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[14]

- Substance P is a neuropeptide and functions as both a neurotransmitter and as a neuromodulator. It can transmit pain from certain sensory neurons to the central nervous system. It also aids in controlling relaxation of the vasculature and lowering blood pressure through the release of nitric oxide.[15]

- Opioid peptides are neurotransmitters that act within pain pathways and the emotional centers of the brain; some of them are analgesics and elicit pleasure or euphoria.[16]

Neurons expressing certain types of neurotransmitters sometimes form distinct systems, where activation of the system affects large volumes of the brain, called volume transmission. Major neurotransmitter systems include the noradrenaline (norepinephrine) system, the dopamine system, the serotonin system and the cholinergic system.

A brief comparison of the major neurotransmitter systems follows:

| System | Origin [17] | Effects[17] |

|---|---|---|

| Noradrenaline system | locus coeruleus |

|

| Lateral tegmental field | ||

| Dopamine system | dopamine pathways: | motor system, reward, cognition, endocrine, nausea |

| Serotonin system | caudal dorsal raphe nucleus | Increase (introversion), mood, satiety, body temperature and sleep, while decreasing nociception. |

| rostral dorsal raphe nucleus | ||

| Cholinergic system | pontomesencephalotegmental complex |

|

| basal optic nucleus of Meynert | ||

| medial septal nucleus |

Drug effects

Drugs can influence an animal's behavior by altering neurotransmitter activity. For example, drugs can decrease the rate of synthesis of neurotransmitter by affecting the synthetic enzyme(s) for that neurotransmitter. When neurotransmitter synthesis is blocked, the amount of neurotransmitter available for release is lowered, resulting in a decrease in neurotransmitter activity. Some drugs block or stimulate the release of specific neurotransmitters. Alternatively, drugs can prevent neurotransmitter storage in synaptic vesicles by causing the synaptic vesicle membranes to leak. Drugs that prevent a neurotransmitter from binding to its receptor are called receptor antagonists. For example, drugs used to treat patients with schizophrenia such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and clozapine are antagonists at receptors in the brain for dopamine. Other drugs act by binding to a receptor and mimicking the normal neurotransmitter. Such drugs are called receptor agonists. An example of a receptor agonist is Valium, a benzodiazepine that mimics the effect of the endogenous neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to decrease anxiety. Other drugs interfere with the deactivation of a neurotransmitter after it has been released, thereby prolonging the action of a neurotransmitter. This can be accomplished by blocking reuptake or inhibiting degradative enzymes. Lastly, drugs can also prevent an action potential from occurring, blocking neuronal activity throughout the central and peripheral nervous system. Drugs such as tetrodotoxin that block neural activity are typically lethal.

Drugs targeting the neurotransmitter of major systems affect the whole system; this fact explains the complexity of action of some drugs. Cocaine, for example, blocks the reuptake of dopamine back into the presynaptic neuron, leaving the neurotransmitter molecules in the synaptic gap longer. Since the dopamine remains in the synapse longer, the neurotransmitter continues to bind to the receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, eliciting a pleasurable emotional response. Physical addiction to cocaine may result from prolonged exposure to excess dopamine in the synapses, which leads to the downregulation of some postsynaptic receptors. After the effects of the drug wear off, one might feel depressed because of the decreased probability of the neurotransmitter binding to a receptor. Prozac is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), which blocks re-uptake of serotonin by the presynaptic cell. This increases the amount of serotonin present at the synapse and allows it to remain there longer, hence potentiating the effect of naturally released serotonin.[18] AMPT prevents the conversion of tyrosine to L-DOPA, the precursor to dopamine; reserpine prevents dopamine storage within vesicles; and deprenyl inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO)-B and thus increases dopamine levels.

Diseases may affect specific neurotransmitter systems. For example, Parkinson's disease is at least in part related to failure of dopaminergic cells in deep-brain nuclei, for example the substantia nigra. Levodopa is a precursor of dopamine, and is the most widely used drug to treat Parkinson's disease.

Common neurotransmitters

Precursors of neurotransmitters

While intake of neurotransmitter precursors does increase neurotransmitter synthesis, evidence is mixed as to whether neurotransmitter release (firing) is increased. Even with increased neurotransmitter release, it is unclear whether this will result in a long-term increase in neurotransmitter signal strength, since the nervous system can adapt to changes such as increased neurotransmitter synthesis and may therefore maintain constant firing.[20] Some neurotransmitters may have a role in depression, and there is some evidence to suggest that intake of precursors of these neurotransmitters may be useful in the treatment of mild and moderate depression.[20][21]

Dopamine precursors

L-DOPA, a precursor of dopamine that crosses the blood–brain barrier, is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

Norepinephrine precursors

For depressed patients where low activity of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine is implicated, there is only little evidence for benefit of neurotransmitter precursor administration. L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine are both precursors for dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. These conversions require vitamin B6, vitamin C, and S-adenosylmethionine. A few studies suggest potential antidepressant effects of L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine, but there is much room for further research in this area.[20]

Serotonin precursors

Administration of L-tryptophan, a precursor for serotonin, is seen to double the production of serotonin in the brain. It is significantly more effective than a placebo in the treatment of mild and moderate depression.[20] This conversion requires vitamin C.[14] 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), also a precursor for serotonin, is also more effective than a placebo.[20]

Degradation and elimination

A neurotransmitter must be broken down once it reaches the post-synaptic cell to prevent further excitatory or inhibitory signal transduction. For example, acetylcholine (ACh), an excitatory neurotransmitter, is broken down by acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Choline is taken up and recycled by the pre-synaptic neuron to synthesize more ACh. Other neurotransmitters such as dopamine are able to diffuse away from their targeted synaptic junctions and are eliminated from the body via the kidneys, or destroyed in the liver. Each neurotransmitter has very specific degradation pathways at regulatory points, which may be the target of the body's own regulatory system against recreational drugs.

Agonists

An agonist is a chemical capable of binding to a receptor, such as a neurotransmitter receptor, and initiating the same reaction typically produced by the binding of the endogenous substance.[22] An agonist of a neurotransmitter will thus initiate the same receptor response as the transmitter.[23]

Nicotine, found in tobacco, is an agonist for acetylcholine at nicotinic receptors.[24] Opiate agonists include morphine, heroin, hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, and methadone. These drugs activate mu opioid receptors that typically respond to endogenous transmitters such as enkephalins. When these receptors are activated, individuals experience euphoria, pain relief, and drowsiness.[24]

See also

- Gasotransmitters

- Kiss-and-run fusion

- Nervous system

- Neuromuscular transmission

- Neuropeptide

- Neuropsychopharmacology

References

- ^ "Neurotransmitter" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Elias, L. J, & Saucier, D. M. (2005). Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston: Pearson

- ^ a b c Robert Sapolsky (2005). "Biology and Human Behavior: The Neurological Origins of Individuality, 2nd edition". The Teaching Company.

see pages 13 & 14 of Guide Book

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. McGraw Hill. 2009 ISBN 0-07-727620-5

- ^ "Junctions Between Cells". Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 38738, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=38738instead. - ^ Kodirov,Sodikdjon A., Shuichi Takizawa, Jamie Joseph, Eric R. Kandel, Gleb P. Shumyatsky, and Vadim Y. Bolshakov. Synaptically released zinc gates long-term potentiation in fear conditioning pathways. PNAS, October 10, 2006. 103(41): 15218-23. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607131103

- ^ Nitric oxide and other gaseous neurotransmitters

- ^ Glutamate: Seizures and strokes- PLoS Biol. 2006 November; 4(11): e371. Published online 2006 October 17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040371 by author Liza Gross- Courtesy Public Library of Science (2006); PubMed (PMC) of NCBI, Retrieved 2013-16-13

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21729715, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21729715instead. - ^ Orexin receptor antagonists a new class of sleeping pill, National Sleep Foundation.

- ^ http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/potm/2005_11/Page2.htm

- ^ Schacter, Gilbert and Weger. Psychology.United States of America.2009.Print.

- ^ a b University of Bristol. "Introduction to Serotonin". Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ http://www.wellnessresources.com/health_topics/sleep/substance_p.php

- ^ Schacter, Gilbert and Weger. Psychology. 2009.Print.

- ^ a b Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 474 for noradrenaline system, page 476 for dopamine system, page 480 for serotonin system and page 483 for cholinergic system. ISBN 0-443-07145-4.

- ^ Yadav, V.; Ryu, Je-Hwang; Suda, Nina; Tanaka, Kenji F.; Gingrich, Jay A.; Schütz, Günther; Glorieux, Francis H.; Chiang, Cherie Y.; Zajac, Jeffrey D.; et al. (2008). "Lrp5 Controls Bone Formation by Inhibiting Serotonin Synthesis in the Duodenum". Cell. 135 (5): 825–837. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059. PMC 2614332. PMID 19041748.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first13=missing|last13=(help);|first14=missing|last14=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Lin Y, Hall RA, Kuhar MJ (October 2011). "CART peptide stimulation of G protein-mediated signaling in differentiated PC12 cells: identification of PACAP 6-38 as a CART receptor antagonist". Neuropeptides. 45 (5): 351–358. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2011.07.006. PMC 3170513. PMID 21855138.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Meyers, Stephen (2000). "Use of Neurotransmitter Precursors for Treatment of Depression" (PDF). Alternative Medicine Review. 5 (1): 64–71. PMID 10696120.

- ^ Van Praag, HM (1981). "Management of depression with serotonin precursors". Biol Psychiatry. 16 (3): 291–310. PMID 6164407.

- ^ . Merriam-Webster http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/agonist.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Drug Receptor Interactions". Virtual Chembook, Elmhurst College.

- ^ a b Fallows, Zak. MIT MedLinks. Center for Health Promotion and Wellness at MIT Medical http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/SP/SP.236/S09/lecturenotes/drugchart.htm.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Molecular Expressions Photo Gallery: The Neurotransmitter Collection

- Brain Neurotransmitters

- Endogenous Neuroactive Extracellular Signal Transducers

- Neurotransmitter at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- neuroscience for kids website

- brain explorer website

- wikibooks cellular neurobiology