The Flavian Palace, normally known as the Domus Flavia, is part of the vast Palace of Domitian on the Palatine Hill in Rome. It was completed in 92 AD by Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus,[1] and attributed to his master architect, Rabirius.[2]

Domus Flavia on the Palatine | |

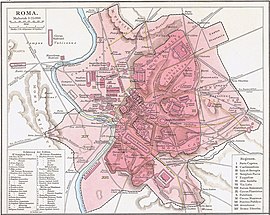

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regio X Palatium |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′3″N 12°29′21″E / 41.88417°N 12.48917°E |

| Type | Domus |

| History | |

| Builder | Domitian |

| Founded | 92 AD |

The term Domus Flavia is a modern name for the northwestern section of the Palace where the bulk of the large "public" rooms for official business, entertaining and ceremony are concentrated.[3] Domitian was the last of the Flavian dynasty, but the palace continued to be used by emperors with small modifications until the end of the empire.

It is connected to the domestic wing to the southeast, the Domus Augustana, a name which in antiquity may have applied to the whole of the palace.[4]

Layout

editThe Domus Flavia is built mainly around a large peristyle courtyard which was surrounded by many elaborate rooms of impressive height, of which only a few 3 m thick walls remain of 16 m height, half the original. It was built upon Nero's earlier palace (Domus Transitoria and Domus Aurea) and followed some of its layout, as excavations have shown.[5] On the northeastern side, the huge aula regia (royal hall) was the central and largest room, flanked by smaller reception rooms, the so-called Basilica and Lararium.

The northern exterior of these three rooms had a portico that continued from the west side and which formed the main entrance to the palace facing those coming up on the road from the forum.[6]

Aula Regia

editThis was an enormous rectangular hall used as an audience chamber, to host important receptions and embassies. An apse is built into the short south wall, where the emperor would have been seated to hold his audiences; on either side of the apse are doorways opening right onto the peristyle. On the north side the Aula opened on to a monumental portico with Carystian marble columns, overlooking the palace forecourt and from where the emperor received the salutatio, the traditional morning ceremony.

The poet Statius, a contemporary of Domitian, described the splendour of the Flavian Palace, particularly the Aula Regia,[2] in Silvae, IV, 2:

Awesome and vast is the edifice, distinguished not by a hundred columns but by as many as could shoulder the gods and the sky if Atlas were let off. The Thunderer’s palace next door gapes at it and the gods rejoice that you are lodged in a like abode […]: so great extends the structure and the sweep of the far-flung hall, more expansive than that of an open plain, embracing much enclosed sky and lesser only than its master.[7]

Although the remains are mainly of low walls today, they would have stretched upwards 30 metres (98 feet) from floor to ceiling, capped by a pitched roof whose 26 m-long (85 ft) beams, probably from Lebanon, must have been concealed beneath a coffered ceiling.[8] The walls were covered in exotic marble veneer and inset with eight niches which held colossal statues, interspersed with purple Phrygian marble columns and capped by an elaborately carved frieze. Two huge statues of metallic-green Bekhen stone (an especially prized sandstone from Egypt)[5] representing Hercules and Bacchus were found in situ during excavations in the 18th century; they became part of the Farnese Collection and are housed in the Archaeological Museum in Parma.[9]

Basilica

editSo-called as its plan resembled a basilica in the forum or a later church, the Basilica is a long room with a central nave and a more private room where the Emperor may have held his council to take political and administrative decisions concerning the Empire. Beneath the Basilica the Aula Isiaca[10] has been excavated, a room with frescoes of about 30 BC and probably once part of the Domus Augusti.[11] This was in turn built over by Nero's Domus Transitoria.

Lararium

editMisnamed by 18th century excavators as a shrine for the Lares (household gods),[9] it was more likely a room for the Praetorian Guard since it is immediately east of the Clivus Palatinus, where visitors to the palace would have arrived. Behind the "Lararium" was once a staircase providing access to the Domus Augustana below which parts of the earlier House of the Griffins have been excavated and from which exquisite decorations have been removed to the Palatine Museum.

Peristyle

editThe main entrance to the west led first into the Aula Ottagonale with elaborate triclinia on each side, and then into a huge peristyle garden almost completely occupied by a lake-like pool in the centre of which was a unique octagonal island with a labyrinthine pattern of channels and with fountains, all veneered in precious marble.[12]

The columns around the peristyle were of yellow Numidian marble, and supported an elaborate sculpted entablature beneath the roof.[13]

Banquet Hall

editThe cenatio or Banquet Hall is on the southwest side of the peristyle and is the 2nd largest room in the Palace. Like the Aula Regia, it was extravagantly decorated, with several tiers of columns in exotic marbles and a frieze.[14] From the cenatio guests could look out through large windows onto the peristyle lake and fountain or onto two courtyards at the sides with elaborate oval marble fountains surrounded by yellow Numidian marble columns. The centre of the southern wall of the hall has an apse surrounded by two passages which allow access to the library of the temple of Apollo. The floor of the hall is covered with marble dating from the early 4th century though the hypocaust beneath dates from the 120's (Hadrian). This heating system suggests that this hall served as a banqueting hall in the winter and has been identified with the Cenatio Iovis mentioned in ancient literary sources.[15]

Martial described a banquet given by Domitian there:

Great as is reported to have been the feast at the triumph over the giants, and glorious as was to all the gods that night on which the kind father sat at table with the inferior deities, and the Fauns were permitted to ask wine from Jupiter (i.e. Domitian); so grand are the festivals that celebrate your victories, O Caesar; and our joys enliven the gods themselves. All the knights, the people, and the senate, feast with you, and Rome partakes of ambrosial repasts with her ruler. You promised much; but how much more have you given! Only a sportula was promised, but you have set before us a splendid supper.[16]

The cenatio is built upon two earlier versions both built by Nero as part of his palace, dating from before (the Domus Transitoria) and after (the Domus Aurea) the Great Fire of Rome in 64, similar in layout to the upper floor,[17] and which are mostly still intact under the later floor.[18] Also the exquisite marble floors of the fountains belong to Nero's palace. It comprises a superb design of flowers and climbing plants using red and green Porphyry, Numidian yellow and red, and Phrygian white and yellow. The border is of panels of pink-grey Chian marble framed in green porphyry.

See also

editBibliography

edit- Coarelli, Filippo,Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press; 2014.

- Platner, Samuel Ball & Ashby, Thomas, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press, London; 1929.

References

edit- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. XI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- ^ a b Darwall-Smith, Robin Haydon. Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Brussels: Latomus Revue D'Etudes Latines, 1996.

- ^ Robathan, Dorothy M. "Domitian's 'Midas-Touch'". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 73 (1942): 130-144.

- ^ Coarelli, 2014; p.146

- ^ a b Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 135

- ^ Archaeological Guide to Rome, Adriano La Regina, 2005, Electa p 64 ISBN 88-435-8366-2

- ^ Statius. Silvae IV. Trans. K.M. Coleman. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- ^ Coarelli, 2014; p=147-8

- ^ a b Coarelli, 2014; p=148

- ^ "Aula Isiaca".

- ^ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 148

- ^ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 134

- ^ Platner & Ashby, 1929; p.160

- ^ Darwall-Smith, Robin Haydon. Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Brussels: Latomus Revue D'Etudes Latines, 1996

- ^ Statius, Silvae 4.2 18-31 (AD 93-4)

- ^ Martial Ep. 8, 50 Bohn's Classical Library (1897) https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/martial_epigrams_book08.htm

- ^ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 136

- ^ "Nero's Domus Transitoria on the Palatine to open to the public". Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

External links

edit- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

Media related to Domus Flavia at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Domus Transitoria |

Landmarks of Rome Flavian Palace |

Succeeded by House of Augustus |